Back in 1974 at Watkins Glen for the United States Grand Prix, I got the chance to sit down with Mario Andretti – in the Vel’s Parnelli Jones team’s section of the Glen circuit’s Technical Centre – and hear from him about his life and career that far. Mario came across as a hyper-competitive sportsman of great – and continuing – achievement and experience and, as a man, he was friendly and engaging and one who conducted himself in a gently distinguished (and highly impressive) manner.

To me, as a hopeless race reporter – by temperament far too shy and reserved ever to ask questions of anyone to whom I had not yet been introduced – the time Mario gave me that day seemed incredible. How had I got to him? Well, both Vel’s Parnelli designer Maurice Phillippe and team manager Andrew Ferguson were fellow Brits, ex-Team Lotus in England.

I knew both well from Lotus days, and it was Andrew who overcame my natural reticence – called me over and said “Hey Mario – here’s someone you ought to meet – he’s OK”. So, there at the Glen that day, I taped a long conversation with America’s finest Italian-born racing driver. And here’s part two of the feature story based upon it that I put together over the next few days. – Doug Nye

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Continued from Part One…

The 1965 USAC big car season opened at Phoenix, Arizona, where Mario punched Dean’s lightweight roadster into the lead ahead of all the Lotus-based rear-engined cars. Then Johnny Rutherford spun in front of him and set him back to finish sixth.

Meanwhile, Clint Brawner had done a deal with John Zink, owner of the first Brabham Indy car, to copy it and build two updated Ford V8-powered replicas; one for the Dean team and one for Zink’s. The car was built, and it had scarcely turned a wheel before Andretti ran it so successfully at Indy. He went there with a second place at Trenton under his belt, and his fearless performance at the Speedway, swooping up within inches of the retaining wall out of the high-speed turns, finally made his name. It was Mario’s psychology which was right.

“Indy was, and is, a big myth in everybody’s mind. All the old-timers there look at ya and say ‘OK kid, don’t get too cocky, this is Indy’. So you think about it and you sit down and then you think ‘Shit, I’m not gonna get psyched. This is just a speedway like any other’. So you get prepared and you get it right and you do it right. Indy is special because everybody knows about it—you can’t do things there quietly—but otherwise, the Indy thing is a myth.

“What’s more difficult on the Championship circuit? I tell you, Trenton’s more difficult now. It’s 1½-miles and they’ve got a right-hand dogleg curve in the back-stretch. That dogleg’s a pig ’cos the cars can’t be set-up for it. You’ve gotta be so right through there. . .”

After his third place at Indy, which earned him $42,500, Mario won the Hoosier Grand Prix, was second in five more races and won the USAC Championship with 3,110 points. It had been his first full season, and he was the Rookie Champion. He was only 25 years old.

Mario Andretti circa 1966. Photo by Bernhard Cahier

In 1966, he won the title again, winning eight of the 15 qualifying races outright. At Indy, he qualified squarely on pole position with a new four-lap average of 165.899 mph and a one-lap record of 166.238 mph. He led for the first 16 laps until sidelined by valve trouble, to be classified a sorry 18th. Otherwise, his domination was complete.

Versatility is Andretti’s keynote. “I never retired from any form of racing’, he says, and early in 1967 he made his debut in NASCAR racing, taking on a Holman and Moody Ford Fairlane in the magic Daytona 500. He qualified for the race at a better than average 177 mph, but it was nothing startling. Then late in practice his red and grey Fairlane stormed around at 182 mph and some of the skeptical NASCAR faithful took a second look at the little man from Pennsylvania.

After a fierce late-race duel with Fred Lorenzen, it was Andretti who stormed to win the 500 —the first USAC and first non-NASCAR driver to do so. ‘Tis said that Kate Firestone was astonished by the man. “Look at him, he’s so teensy!”, she said. The Detroit News commented sagely, “…He’s toughsy and fastsy too…”.

Mario is one of the very few drivers ever to win the Indianapolis 500 (1969) and the Daytona 500 (1967) in their careers. He’s pictured here in the winning machine at Daytona.

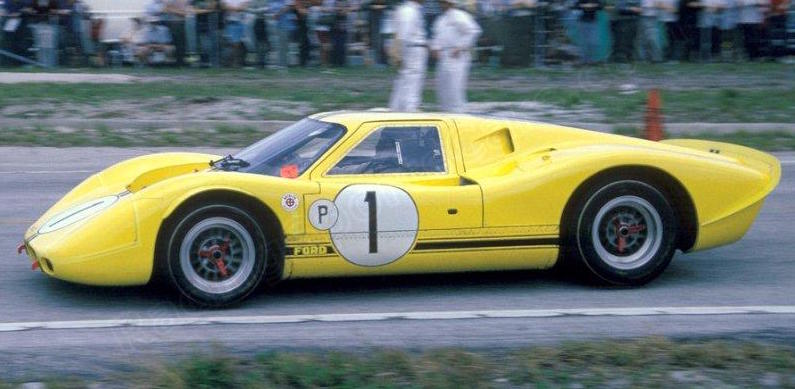

Road racing was the next field to conquer. Mario had run a NART Ferrari in the Sebring 12-Hours the previous year, but a tragedy-darkened run ended in retirement. For ’67 he was paired with Bruce McLaren in the prototype 7-litre Ford Mark IV, and they won. Next day he was in Atlanta, running another 500-mile stock car race until repeated tyre blow-outs snuffed-out his drive against the wall. At Le Mans, he was paired with Lucien Bianchi, and their big Ford was running in second place in the small hours when the Belgian brought it in for refueling and a routine brake pad change.

The team of Bruce McLaren and Mario Andretti won the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1967 driving this prototype of the Ford GT 40 MkIV. Photo: George Boron.

It was then that Mario had one of his biggest frights; “The pads went in backward and cracked the disc. As I braked down into the Esses, right out of the pits, they just jerked the wheel out of my hands and the bitch car hit just about everything. I got to the side of the road when Roger McCluskey appeared, thought I was still in the wreck and smashed up trying to avoid it. Then Jo Schlesser came over the top and smashed his Ford as well oh, what a bitch that was…”.

Indy that year had Andretti on pole for the second time, but he was out of the race when the right front wheel parted company. He won seven Championship rounds and was leading the Rex Mays race at Riverside with only three laps to go when a stop for fuel cost him victory, and what would have been his hat-trick of National titles. Instead, A. J. Foyt topped the ratings.

In December Al Dean died, and Andretti took over the racing stable himself, still with Clint Brawner and Jim McGee preparing the Championship cars. Indy was a disaster as he started from row two and became the first retirement after only two laps, with engine trouble. He fought back in the rest of the series, winning three times and placed second 11 times. But the Riverside race cost him the title again, this time to Bobby Unser, by only 11 points. On road circuits, he had driven for Alfa Romeo at Daytona, and then Colin Chapman offered him a Gold Leaf Team Lotus drive in the Italian and US GPs. He was ruled out of the Italian race because he had a USAC event to do within 24 hours, but at Watkins Glen, he shook everybody by taking pole position in his first Formula 1 race. It all fell apart when the car’s nosecone fell to bits and its clutch failed.

Mario Andretti poses with the STP-sponsored team owned by Andy Granatelli (far right) that won the 1969 Indianapolis 500.

Then came 1969, backing from Andy Granatelli and STP and a first win in the Indy 500. During practice, Mario crashed very heavily in the Lotus 64, and he raced his ancient Hawk-Ford. “It was just a spare car you know, not even cleaned-off since Hanford. It had just two days of practice and was never out of third. I had to back-off in the race, it showed 260-degrees oil temperature, but we won. It was the first time … it was very satisfying”.

He went on to win eight more races and his third Championship. A works Ferrari ride into second place at Sebring meant a lot to him and with a brutish McLaren-Ford he struggled manfully to two good CanAm sports car placings. Meanwhile, he had great faith in four-wheel drive, and Colin Chapman pinned his Formula 1 hopes on the American’s faith. Unfortunately, “… it was worth a try, but it proved absolutely not worthy of road racing. Tyre development solved the traction problem, and anyway, the car’s straightaway speed was down. In a high-speed corner, the things were just fantastic, which is why they worked at Indy, but otherwise, no way…”.

At the Nurburgring, Mario had a short German GP. “I’d never practised with full tanks, an’ then I got a good start and was up with them. But the thing was bottoming on the bumps and then up over that Flugplatz, it bottomed so bad, I caught a wheel on the catch fence and took it off. I didn’t crash, I just slid to a stop but then Vic Elford came over in that McLaren and hit the wheel. He rolled upside down over a drop and I went down and held the car up off his arm on my shoulder and reached in and knocked the switches off. Poor guy, I felt kind of responsible, but what can you do, you know?”

In 1970 Mario was back in a Ferrari, this time a 512 in which he helped Vaccarella and Giunti to win at Sebring. The Granatellis backed him in the ill-conceived McNamara Championship car and in a similarly unsuccessful Formula 1 March. He was fifth in the USAC National Championship, which for him was a big fall. Then came the Formula 1 signing with Ferrari for 1971. “I enjoyed that to no end. It was something I had dreamed of since I was a kid at Lucca and when I won in South Africa it was the most satisfying thing I’d ever achieved.

“Psychologically it was a very great thing, and the win at Ontario was good too because those cars were the real t’oroughbreds. It’s who you beat that matters—I’ll take wins any way they come—but to be in front of Stewart both times was great…”

That season was his last with the Granatellis (“I’m still personally good friends with Andy, but I couldn’t agree with the way things were done there, those brothers, you know?”).

He was put out of Indy in an early four-car crash, and second at Trenton was his best finish of the year. He was ninth in the point standings and left the STP fold to join Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones for 1972.

“That Vel…”, he says, indicating the big-built greying Californian motor dealer smiling happily beside his Formula 1 car, “… he’s such an ent’usiast you can’t believe it. I wanna race and be competitive and that’s why I joined Vel’s — they’re 200 percent…”

The Maurice Phillippe-designed Viceroy Special which Mario drove was not as competitive as had been hoped. “But the biggest problem with the car was its big build-up. First time we ran we had news people crawling all over it, and when it wasn’t quite right we got all the crap, you know. I could’ve killed that PR man!”

Most of Mario’s winning that season was with the Ferrari sports car team, partnering Jacky lckx, for they took the Daytona, Sebring and Brands Hatch Championship rounds. “I enjoyed that long-distance racing, it disciplines you to go quick without destroying the car”, while in USAC “I led nearly every race only to blow engines. We had a piston problem…” That was expensive, as at Indy where Mario’s detuned car was fifth at 190 laps only to run out of fuel and be placed eighth. Team-mate Joe Leonard ran his identical Samsonite Special more slowly and gained in reliability to win the Championship.

The winning Ferrari 312PB (#0888) of Mario Andretti and Jackie Ickx at Daytona in 1972. The race was shortened to 6 hours that year. The pair would repeat at Sebring two months later. (Photo: Levetto)

The ’73 season saw Vel’s Parnelli using re-designed Phillippe cars in which Andretti won early on at Trenton, and set a world’s closed-circuit outright lap record at Texas World Speedway. Thereafter fortunes again took a dive, in European eyes it seemed as though Andretti was running out of steam, we didn’t hear much of him any more…

Then in April this year, he shared the winning Alfa Romeo in the Monza 1,000 Kms, at the seat of Italian motor racing. That must have meant a lot? “Yeah, that was OK, but it was sports cars, and who did we beat? The Grand Prix …” a faraway look at the Parnelli car “…would be different”.

The ’74 Parnelli USAC car put in just one race, at Trenton, where Mario put it on pole and led until the engine failed. Vel’s Parnelli wheeled a Formula A/5000 Lola into their Torrance, California, workshops, and Mario took it out on to the American Championship road circuits, winning at Elkhart Lake, Watkins Glen and Riverside. “ On a road circuit Mario is as sharp as ever”, they said, and when it came to the team’s Grand Prix debut with their brand-new “… four-inch lower Lotus 72” he proved it.

“Formula 5000 has become good racing,” he says reflectively, “… and lucrative too, with purses of $55,000-60,000 for the races, and $16,000-18,000 for a win. But that Brian Redman, you know, he has been really tough competition, fantastically quick. Jim Hall’s operation too, they’re tough. But it’s good practice for Formula 1, and this is where I wanna be. I figure I’m not getting’ any younger, and I’m trying to do it seriously now. Next year I’m gonna do Formula 1, 5000 and the three 500-mile track races, I guess that’s enough…”

Andretti is married, has two sons and a small daughter, and still lives in Nazareth where they have named a street (Victory Lane) in his honour. His last Fl race previous to the Vel’s Parnelli venture was the Glen in ’72 when his Ferrari was placed sixth and at least some of the fans recalled that. While we were talking a teenaged kid came bursting in, eyes aflame with enthusiasm (if not much knowledge). “ Hey, Mario, I’m looking for ya, man. You racin’ this afternoon? What ya drivin’? Ya drivin’ Lotus? Ya drivin’ Ferrari?” etc, etc. Andretti’s natural reaction was “ thanks, but excuse us, we’re talking here”, slowly changing to muted irritation as the kid’s ignorance showed. He eventually backed off moaning “Hey Mario, man, I was lookin’ for ya, man…lookin’ for ya…” to be swallowed up in the crowd.

Mario Andretti turned his powerful shoulders, brown eyes darkened; “That kinda thing bugs the bell outa me”, he snorted, “…but I guess he’s got ent’usiasm”, and his tanned face creased into a grin. Maybe he was thinking where his “ent’usiasm” has put him, and next season he’s going to be running hard to improve on that.

“At Mosport, we had a little rev problem, and were over-winged, but we hung in there for seventh. Here we’ve learned a little more. We were getting it all to work for us until that pump died on the start, and we got disqualified. But that’s racing, you know… Hopefully, we can make it a better car yet, and really, it’s so good to be here again in Formula 1, it really is. It’s the thoroughbred of racing, you know it’s the top…” Mario Andretti, Watkins Glen, October 1974.

Mario Andretti wheels the Vel’s Parnelli Jones Formula One car at Watkins Glen in 1974. Photo: International Motor Racing Research Center.

Back in 1974 at Watkins Glen for the United States Grand Prix, I got the chance to sit down with Mario Andretti – in the Vel’s Parnelli Jones team’s section of the Glen circuit’s Technical Centre – and hear from him about his life and career that far. Mario came across as a hyper-competitive sportsman of great – and continuing – achievement and experience and, as a man, he was friendly and engaging and one who conducted himself in a gently distinguished (and highly impressive) manner.

To me, as a hopeless race reporter – by temperament far too shy and reserved ever to ask questions of anyone to whom I had not yet been introduced – the time Mario gave me that day seemed incredible. How had I got to him? Well, both Vel’s Parnelli designer Maurice Phillippe and team manager Andrew Ferguson were fellow Brits, ex-Team Lotus in England.

I knew both well from Lotus days, and it was Andrew who overcame my natural reticence – called me over and said “Hey Mario – here’s someone you ought to meet – he’s OK”. So, there at the Glen that day, I taped a long conversation with America’s finest Italian-born racing driver. And here’s the feature story based upon it that I put together over the next few days. – Doug Nye

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

It took just under four minutes for Mario Andretti to make himself an ace. To be precise he took 3 minutes 46.63 seconds, pelting his Dean Van Lines Special round Indianapolis to steal pole position and set new four-lap and one-lap qualifying speed records, first time out on the Speedway.

Mario Andretti poses in his Dean Van Lines Brawner-Hawk after qualifying fourth for his first Indianapolis 500 in 1965. He would finish in third and win rookie of the year honors.

That was nine years ago, in 1965, and until then Mario had been just another successful young kid from the dirt tracks, full of apparent potential in his first few USAC Championship races, but yet to deliver the goods. As he pulled his bulbous white Ford-powered car into the Indy pit lane the crowd roared themselves hoarse at his performance. But the wiry 25-year-old Italian immigrant was already looking over his shoulder. Jimmy Clark followed him out onto the Speedway, and he turned in four consecutive laps over 160 mph to steal Andretti’s pole position and his records. At the end of the day, A. J. Foyt had taken top qualifying honours, and Mario was fourth quickest, bumped back to the inside of the second row by Dan Gurney. In the race, his first Indy 500, the tough little man from Nazareth, Pa, then drove like a veteran, despite an intermittent fuel system fault afflicting his car. He lay with the leaders from the start, hounding Rufus Parnelli Jones all the way until the race drew towards its dramatic finish.

Clark rushed home to win for Lotus and Ford, nearly two minutes ahead of Jones’ year-old Lotus which was in deep trouble. It was running low on fuel, and with Andretti just 20-seconds astern, Parnell dared not stop to top-up. On the last lap, Jones zig-zagged his faltering car across the line, just managing to wash the last remaining dregs of fuel into the pick-up pipes, to hold off Andretti by just six seconds.

So the mercurial Rookie was third in his Indianapolis debut, winning a well-deserved Stark & Wetzel Rookie of the Year award, and also being voted Driver of the Year by the Hoosier Auto Racing Fans. They knew what they were talking about. He ended the season by winning the USAC National Championship, and he repeated this feat the following year.

Since then Mario Andretti has become Internationally-acknowledged as one of the most versatile and capable race drivers of all time. He has won on dirt and paved ovals; he has won stock car races on the high-banked super-speedways of the American deep south; he has won on road circuits in USAC Championship cars, long-distance sports car classics, in Formula 5000 and in Formula 1.

In 1969, he won the prestigious Indy 500, and in 1971 he won the South African Grand Prix. He is back in Formula 1, driving for the prime target in that now far-off Indianapolis 500 —for Parnelli Jones. His brand-new Maurice Phillippe-designed Vel’s Parnelli VPJ4 made its debut in ‘Super-Wop’s’ hands in the Canadian GP, and he perched it briefly on pole position for the United States GP at the Glen. Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones now have their team poised to tackle a full World Championship season next year, and after their spoiled Watkins Glen performance, they obviously mean business.

I found Andretti in the Kendall Tech Centre at the Glen after the Grand Prix’s first practice sessions had ended. He had set fastest time. The car was on pole overnight, and there was no mistaking the heart-warming rosy glow around the Vel’s Parnelli work bay.

The Tech Centre at the Glen is a great gloomy barn of a place, fenced off into a series of bays with a spectator-packed aisle down the centre. They pay a dollar a time to pack into the place for a close-up look at the great cars and great names of the day. The place is reminiscent of any English country-town’s covered cattle market, but here the all-pervasive pong is one of synthetic rubber, oil and cleaning fluid, instead of you know what.

Mario is a deceptive character, small in stature, broad-shouldered and powerfully built. He’s a big man in attainment, and he wears competitive nature like a badge. It’s as unmistakable as the Ferrari escutcheon which he still wears proudly on his Firestone jacket.

Motor racing was just starting its final pre-war season, confined to Italian territory, when Mario and Aldo Andretti were born as twins on February 28, 1940. Father was a farmer, and the family had seven farms in lstria, around Trieste where the Adriatic bites the division between Italy and Yugoslavia. At the end of the war, the Andrettis’ land was swallowed by a political settlement with Yugoslavia. The family wanted to stay Italian as the border was adjusted, so they abandoned their heritage to the new communist state and joined thousands of refugees moving westward.

Andretti is matter-of-fact about what must have been at first a confusing and later a bitter experience for a young kid. “We left in 1948, and lived in a refugee camp at Lucca—it’s near Pisa—for the next seven years. Yeah, it was tough. There were twen’y-seven families all living in one big room, about the size of this…”, he said, waving his hand at the Tech Centre’s walls.

“It was in Lucca that Aldo and I started around the local garage. The guy who ran it had ambitions for his son in racing, bought a Stanguellini and kind of pushed him into it. We were only around t’irteen or fifteen, and we used to help around and just soaked up the racing atmosphere. I remember there was one really great day, we went to Modena to pick up a ’53 Ferrari for the Mille Miglia, that was a great thing… “.

“We had an uncle, he was a priest, called Ghersa Quirino, and I guess he sympathised with our ent’usiasm. He bought us a 175cc MV motorcycle, without our parents knowing, and we raised hell with that around Lucca— all these little tight streets and alleys you know, it was the ideal training ground. We really loved motorcycle road racing…” (expansive gesture with the hands) “…any kind of road racing, and then we had great aspirations to get properly involved sometime.”

The family had relatives already living in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, and they acted as sponsors to help Mario’s folks emigrate there in the late ’fifties. By that time Mario and Aldo had driven their first motor races in an 85-horsepower Stanguellini-Fiat Formula Junior car, and they came to America hoping that at least one thing would not have changed much in their new life.

They were in luck. Three days after arriving in Nazareth they heard the rumble of modified stock cars racing on a nearby track: “We got over there quick as we could. We looked at the people driving and at the cars they drove and thought ‘hey, this looks easy’, and that was that….”.

The twins had another uncle, Louis Messenlehner (“…he was German, you know, on my mother’s side…”) who helped them to learn the language and, clandestinely so their parents would not suspect, to put together a modified stock car of their own.

“It was an old ’48 Hudson. Marshall Teague had been king in those cars until he was killed the year before we got started, but his folks and mechanics gave us all their know-how on spring-rates and shockers; it was pretty much unknown sophisticated stuff at that time.

“You had to be 21 before you could race in America, and we were only 17, but Les Young who was a newspaper editor on the ‘Nazareth Key’ helped camouflage our date of birth and we got in there. Aldo won the first race from starting at the back. We won our first three events, you know, we were quite successful all through our stock car days…”.

They had some low notes, as when in their first season (1958) Aldo got the Hudson out of shape and crashed heavily during a race at Hatfield, Pa. He suffered a concussion, and Mario had a hard time convincing Papa that Aldo had accidentally fallen off the top of a truck while watching the racing.

Unfortunately, Aldo was never again to be quite such an accomplished natural driver as his brother, and after trying hard in midget and sprint cars, he sustained severe head injuries through crashing a sprinter in 1969 and hasn’t raced since. Today he lives in Indianapolis, runs a couple of Andretti Firestone tyres stores, and accompanies his brother to most of his races.

In 1958, ’59 and ’60 Mario won over 20 modified stock car events, and in 1961 moved into the single-seater scene on the URC Sprint Car circuit. He was old enough to race legally but had some problems making the transition. “I just didn’t know which way that car was goin’ to go”. He ran with URC until the middle of 1962, when he began driving midgets in ARDC.

It was a rough and tumble schoolroom, of a type simply non-existent in Europe, which provided a staggering amount of experience: “I did 107 races in 1963, you know…

“In Midgets, you can regularly do 80 races on up each year. Sometimes we’d do t’ree races a week, and on Labour Day ’63 I won three races in two meetin’s ! Today just physically you can’t do that, but those Midgets really were the most constructive racing I’ve ever done. I tell you, you never run closer than in Midgets. You’d have 45-50 cars to qualify for only 18 places in the Final, and winning in Midgets can give tremendous satisfaction. I really felt I was accomplishin’ somethin’.”

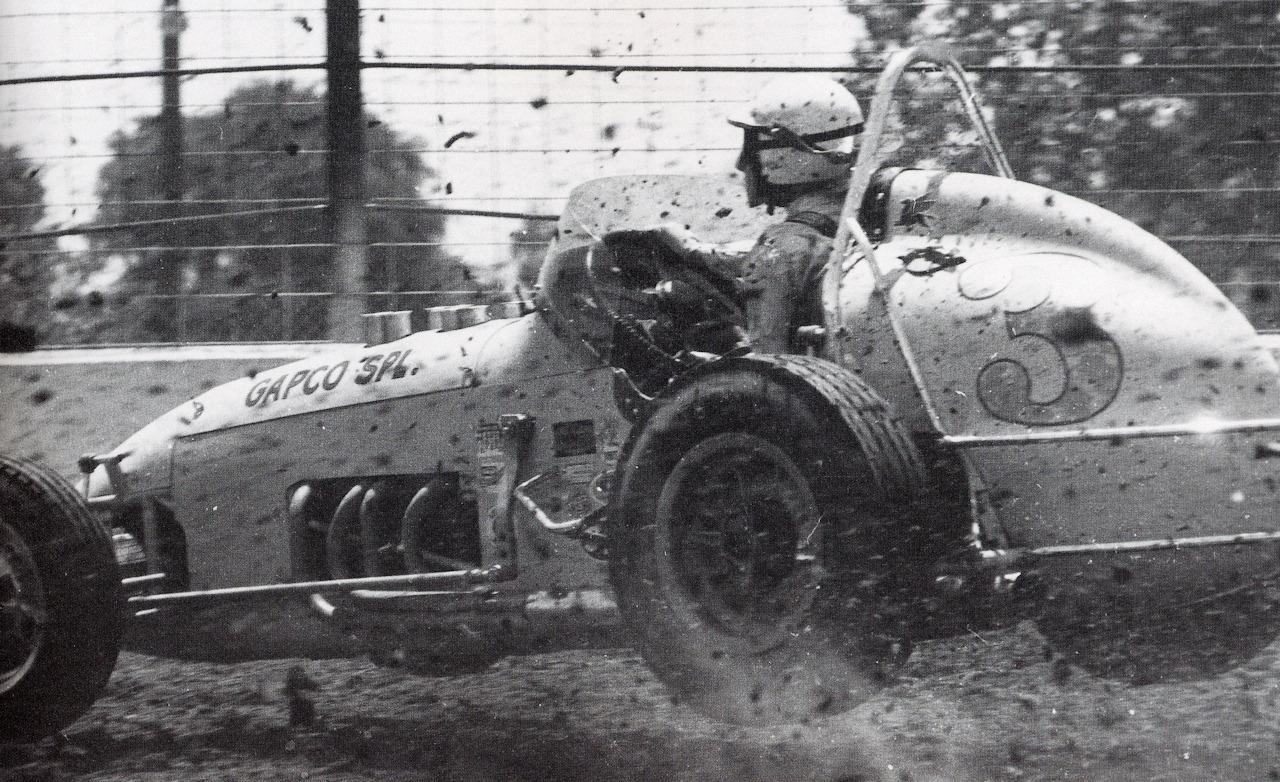

Andretti continued to race Sprint cars on dirt even as his international racing career took off, as pictured here at Terre Haute in 1965.

He drove an Offy-powered Midget for Bill and Ed Mataka that season, and early in 1964, he joined the United States Auto Club to get into Championship racing, to tackle the big-time. “That had been my goal since I started in sprints, you know. When you’re just starting you gotta set your aims high; unreasonably high at the time, and you just gotta get out and get after them. You tell yourself to do it…”, a shake of the head, “Shit, you just tell yourself these things, you know….”

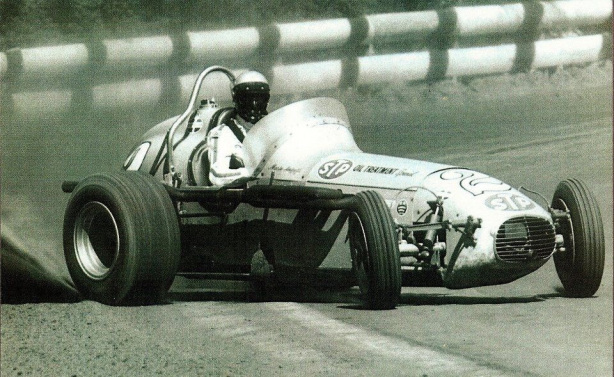

Mario hangs in out in the dirt at Sacramento in 1966.

Mario’s first Championship race was at Trenton, NJ, in March ’64, and it wasn’t too happy a debut. “I was like a fish out of water. I mean I spun three times. I tell you, I just felt incapable! Those paved tracks were hard to drive at first. I was used to hanging my Sprint car out and tossing it around. In comparison those roadsters were a son of a bitch, you had to drive ’em like t’readin’ a needle…”

The story goes that Mario visited Indy that year; just a 24-year-old dirt track driver soaking up the Speedway’s carefully manufactured mystique for the first time. But he wasn’t overawed by the place. He was wandering around Gasoline Alley looking for a drive. He looked up Al Dean’s veteran crew chief Clint Brawner, who had just lost his driver when Chuck Hulse was seriously injured in a sprint crash earlier that month. Rufus Grey, who owned the sprint car Andretti was driving at the time, introduced his young protégé and tried to talk him into Brawner’s Dean Van Lines roadster. When he mentioned that Mario raced sprint cars, Brawner’s sun-sensitive neck apparently reddened, he bawled “Goddammit, sprint’s a dirty word in this garage”, and tossed the hopeful applicants out of the door!

But Brawner had heard of Andretti’s prowess from other sources, and a month later he watched Mario drive at Terre Haute and offered him the Dean drive, mere or less as a trial until Hulse recovered. The compact little Italian jumped at the chance; “In major league racing, I figured there were only a few outfits worth driving for, that were going to produce a winner. I considered Dean one of these, so I t’ought maybe I’m gettin’ into somethin’ good.”

He drove the Dean Van Lines Special in the last eight Championship races of the ’64 season, was third in the Milwaukee ‘200’ and notched sufficient points for 11th in the Championship standings. He drove in 20 sprint races, was third in the standings and highlighted with victory in the Joe James-Pat O’Connor Memorial 100-lapper at Salem.

— Continued in Part Two

This is Part TWO of the behind-the-scenes story of how sports car racing emerged in America during the post-war era, who organized the races and the all-out war that erupted for control. This post is excerpted from the book: “IMSA 1969-1989: The Inside Story of How John Bishop Built the World’s Greatest Sports Car Racing Series”, authored by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, scheduled for publication in January 2019 from Octane Press.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

There was plenty of professional racing going on in the world by the late 1950s. Outside of the U.S., international racing was governed by the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). Some Americans like Phil Hill, Dan Gurney and Carroll Shelby achieved professional status by racing in Europe against the best drivers of the day, but for most drivers in the U.S. racing for money risked the loss of their SCCA licenses.

Bringing international caliber drivers to the U.S. became an obsession for early race organizers like Bill France Sr., the founder of NASCAR, and the leaders of the FIA correspondingly saw the U.S. market as a huge opportunity. With the withdrawal of the AAA from race sanctioning in 1955, representatives from the FIA came to America in 1956 with the intention of hitching their wagon to one of the established sanctioning bodies already functioning in the U.S.: NASCAR, USAC and the SCCA.

The emissaries from Europe met with France Sr., Colonel Arthur Harrington, former president of the AAA Contest Board and one of the founders of USAC, and Jim Kimberley, who represented the SCCA. The leadership at USAC saw this as an enormous opportunity to take control of professional road racing if they could convince the FIA representatives to give them their seal of approval. But France Sr. had other ideas. He understood that if just one organization owned the FIA relationship, it would quickly put the others at a disadvantage. He instead proposed a committee comprised of all three sanctioning organizations, each with the ability to apply for the FIA’s international listings for their events. The FIA agreed and the Automobile Competition Committee of the United States (ACCUS) was formed in 1957. ACCUS continues to operate today as the representative of American racing to the FIA, albeit with more member organizations.

Shortly after the creation of ACCUS, race organizers secured FIA listings for Formula One Grand Prix events at Sebring in 1959 and Riverside in 1960, running them under the FIA banner without a U.S. sanctioning body. These professional events were groundbreaking; they introduced world-class race drivers and their exotic machines to American audiences. By 1961, USAC had taken over the sanction of the L.A. Times Grand Prix and a similar event held at Laguna Seca.

The first Watkins Glen-based Formula One race was held in 1961 under direct FIA sanction. These races, along with Alec Ulmann’s 12 Hours of Sebring held in March, became a powerful magnet for American drivers who wanted in on the action.

Despite the success of these major events, SCCA races were still understood to be strictly amateur. Drivers began to bristle at the draconian restrictions being imposed on them by the Club. They wanted to compete at the next level of motorsport, test themselves against the best from the rest of the world and make some money along the way. But was the penalty for participation worth it?

In response, in the summer of 1961, the SCCA began to ease its restrictions on members participating in certain, designated professional events. But confusion reigned – it wasn’t clear which events were approved and which were not. Ultimately, after much hand-wringing, the Club’s Board once again withdrew public support for professional racing, leaving American drivers in limbo. Privately, however, the Board voted that summer to move forward with a plan that had been drawn up by John Bishop. It was a blueprint for professional racing that put a high priority on reclaiming the sanction of the most important races in the U.S. operating at the time: the 12 Hours of Sebring, The L.A. Times Grand Prix at Riverside, The U.S. Grand Prix at Wakins Glen, and the San Francisco Examiner Grand Prix at Laguna Seca.

Roger Penske on his way to winning the L.A. Times Grand Prix in the Zerex Special at Riverside International Raceway in 1962. The race was sanctioned that year by USAC. Photo credit: IMRRC Archives

USAC held six road racing events in1961 with limited support from SCCA drivers, although some did cross the line. The SCCA licenses for these transgressors were promptly revoked, further fanning the flames of discontent. But the door had been cracked open and it was now just a matter of time before professional racing became a reality at the Club.

There was mass confusion during the 1962 season as USAC and the SCCA sparred over dates, rules and drivers. In the December 1962 issue of Sports Car magazine, the Club announced the formation of the United States Road Racing Championship (USRRC) to be run the next year in classes of cars with engines over 2.0 liters and under 2.0 liters. This was the Club’s first openly professional series, starting with the Daytona Continental in January of 1963.

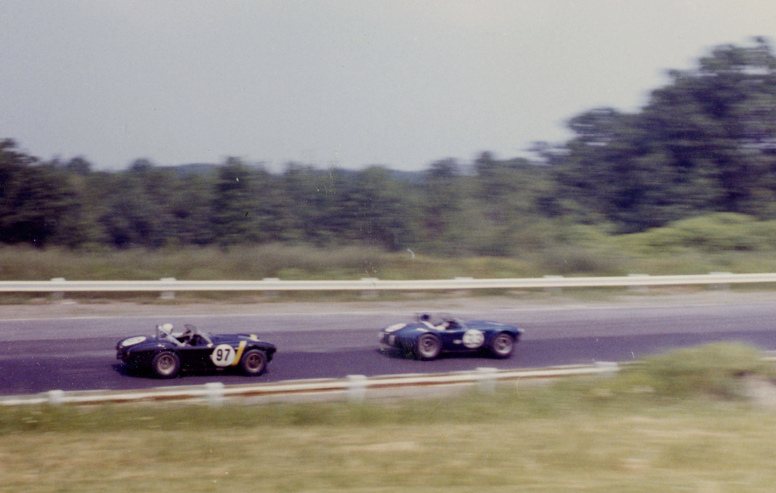

Bob Johnson leads Dave MacDonald during the 1963 USRRC event at Watkins Glen. Both are driving Shelby Cobras, a mainstay of the series in its first year. Photo credit: IMRRC Archives

With full FIA listings and open invitations to professional drivers from both the U.S. and Europe, the USRRC quickly became the go-to sports car racing series in the country. Support for USAC’s road racing events withered, never to return. Over the next two years, the SCCA took over the sanction of the L.A. Times Grand Prix, the San Francisco Examiner Grand Prix at Laguna Seca, the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen and the 12 Hours of Sebring. SCCA drivers that had been patiently sitting on the fence were now able to put both feet in with the new series.

The start of the USRRC race at Watkins Glen in 1964. Photo credit: Ozzie Lyons/© Pete Lyons at petelyons.com

The SCCA quickly followed up the USRRC success with the Can-Am, Trans-Am and Formula 5000 series, further cementing its status as the sanctioning body with the most competitive professional road racing circuits in the U.S. by the late 1960s.

The Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) was founded in 1944 by a group of wealthy sports car enthusiasts from Boston as a kind of gentleman’s club, according to Peter Hylton, SCCA archivist and historian. The original members were all friends that shared the same economic status and liked cars, the more exotic the better. Joining was not easy. Prospective members of the SCCA had to be formally endorsed by an existing member and voted into the Club by the rest of the membership.

Those first meetings consisted of shared meals and conversation followed by rallies on public roads. Soon, the footprint of the SCCA began to grow as it began to sanction races over fixed courses on public roads. The Club expanded westward and southward by formally chartering regional chapters. But even as the Club grew, it always adhered to the notion that racing was strictly an amateur activity and for Club members only.

By 1955, the SCCA had become the sports car road racing alternative to the American Automobile Association (AAA), which sanctioned champ car, sprint car and midget racing on ovals and to the National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR), which ran stock car races in the South and through alliances with promoters in the Northeast, Midwest and on the West Coast. In many respects, the early success of the SCCA reflected the post-war economic boom. As the economy grew, so did the ranks of the middle class. New prosperity brought increased interest in European sports cars like MGs, Jaguars, Porsches, Ferraris, Alfa Romeos, and others. And once these cars were on the street, competition was inevitable.

Racing through the streets of Watkins Glen began in 1948 and Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin in 1950, but racing on public roads was deemed too dangerous after a spectator fatality at Watkins Glen in 1952. Demand for road racing venues escalated quickly, but there were simply not enough purpose-built tracks at the time – building permanent race tracks was an expensive and slow process. The shortage was partly relieved with the help of Curtis LeMay, an Air Force General in charge of the Strategic Air Command (and car guy), who opened up a few decommissioned WWII airfields for racing events.

The 12 Hours of Sebring was held on a decommissioned B-17 training base south of Orlando, Florida starting in 1952. As this photo shows, the condition of the pit area had improved only slightly by 1957. Photo credit: IMRRC Archive

Mike Hawthorne in a D-Type Jaguar during the 12 Hours of Sebring held in 1955, when the race was sanctioned by the AAA. After the debacle at Le Mans later that year, Alec and Mary Ulmann formed the Automobile Racing Club of Florida (ARCF) as an entity to produce and promote the race. The SCCA took over sanction of the Sebring event in 1964. Photo credit: IMRRC Archive

The landscape changed dramatically and suddenly with the infamous disaster at Le Mans in 1955. Pierre Levegh, co-driving with American John Fitch, made contact with a slower car on the main straight, vaulting his Mercedes-Benz into the air, which struck a retaining wall and exploded, sending components into the crowd. Levegh and more than 80 spectators were killed. As a direct result of this horrific accident, the AAA decided to drop out of race sanctioning altogether. This left a void in the sanctioning world that was quickly filled by the newly formed United States Auto Club (USAC), organized at the behest of Indianapolis Motor Speedway owner Tony Hulman.

But rather than just focus just on the AAA’s former turf, USAC had bigger ambitions. It had designs on becoming the single dominant player in all forms of motor racing – short tracks, stock cars and road racing. Knowing the SCCA was committed to amateur racing, USAC announced a professional road racing series for 1958.

USAC ran its first road races at Lime Rock Park, Marlboro Motor Raceway and the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Circuit in 1958, which caught the attention of the top drivers of the day. The concept of racing for money instead of just trophies was enticing. The SCCA Board of Governors hotly debated whether to respond with the Club’s own professional series or to maintain strict, amateur-only status.

In the end, the Board decided to keep the status quo. But as part of this decision, the Board of Governors decreed that SCCA licensed drivers and corner workers who participated in, or assisted with, USAC events would be banished from the Club. Further, it was announced that any SCCA region participating in a racing event where remuneration was offered would have its charter revoked. This form of harsh excommunication was designed to keep the membership in line. Ultimately, this strategy failed, but a seven-year war for control of road racing in America had been formally declared.

TO BE CONTINUED…

After the end of World War II, sports car racing experienced a renaissance, unlike anything America had ever witnessed before. The post-war economy was booming. And when combined with a growing workforce of educated, skilled workers created by the G.I. Bill, it helped create a vibrant American middle class. For the first time since the Great Depression, families began to have money for more than just the basics, including sports cars, which were beginning to show up from exotic places such as Italy, Britain, Germany and other countries.

The small trickle of imported machines grew steadily and the inevitable happened – races started to emerge. This is the behind-the-scenes story of what happened next, how sports car racing emerged in America during the post-war era, who organized the races and the all-out war that erupted for control.

My father, John Bishop, started his career with the SCCA in 1956, at the very beginning of the knock-down fight between the SCCA and USAC over control of professional road racing in America. He later would take over as executive director of the SCCA at the beginning of 1962, putting him squarely in the middle of the drama. What follows is an account of that period, excerpted from the book: “IMSA 1969-1989: The Inside Story of How John Bishop Built the World’s Greatest Sports Car Racing Series,” authored by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, scheduled for publication in January 2019 from Octane Press.

-Mitch Bishop