Origin of International Racing at Watkins Glen by J.C. Argetsinger

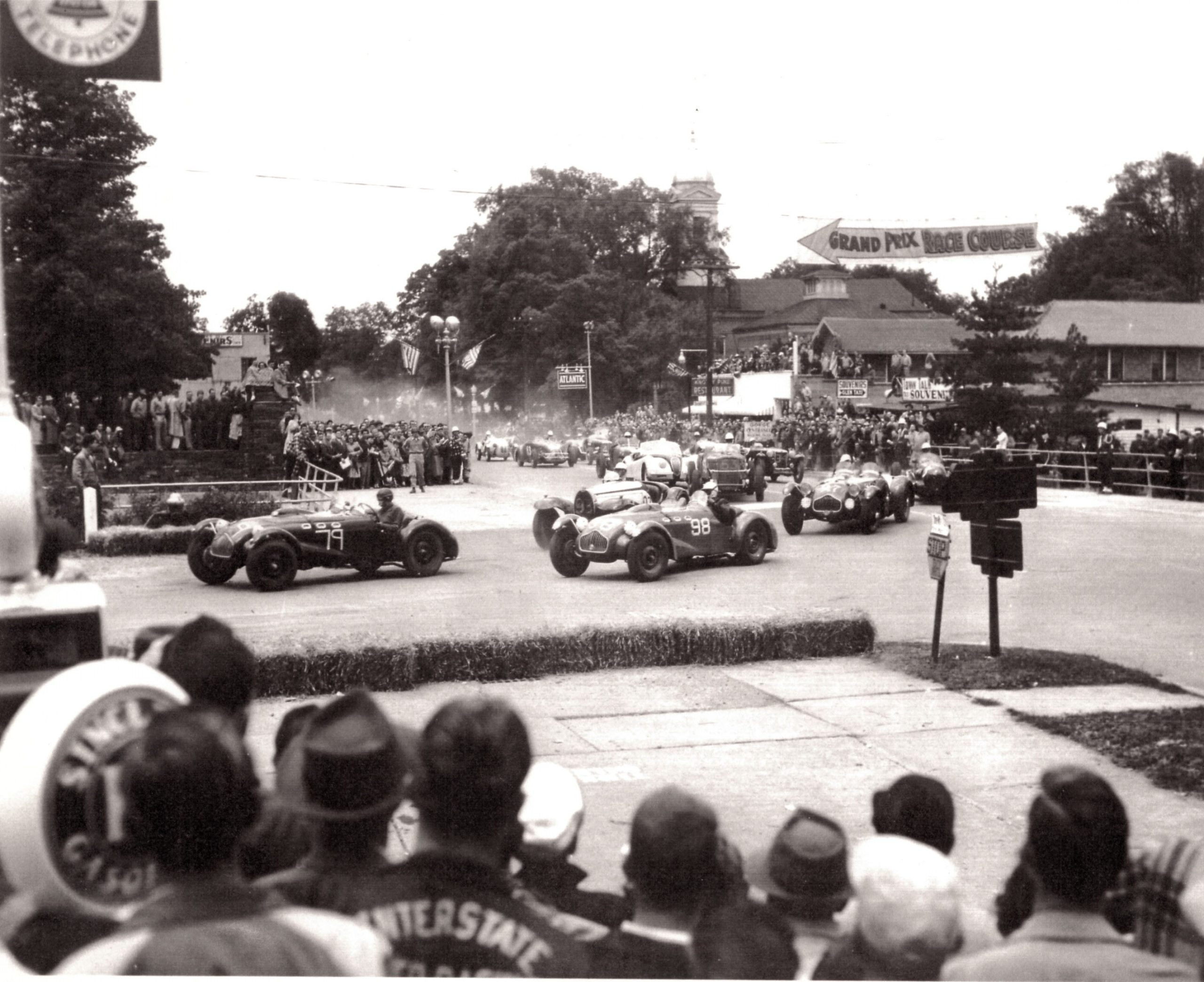

Seventy years ago this fall, road racing in America took a large step forward. Only two years earlier the sport of racing in the streets had been revived at Watkins Glen, New York after a long absence in this country. For its third annual event, September 1950, the race was placed on the world calendar by the Paris-based FIA and billed as the “International Sports Car Grand Prix of Watkins Glen.”

Previously the Watkins Glen race and the few others around the country were club affairs, mostly sponsored by the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA), open only to members. The international designation brought co-sponsorship by the American Automobile Association (AAA), the U.S. representative to the world sanctioning organization. This opened competition to a larger field of contenders.

In the weeks before the race, the caliber of entrants promised to provide exciting racing for the 100,000 spectators who ultimately attended. A number of unaffiliated drivers and members of smaller clubs, such as the New York City-based Motor Sports Club of America (MSCA) and the MG Car Club, were now eligible to compete for the first time.

In addition to the high quality of drivers, the cars entered were state-of-the-art. Briggs Cunningham, always a favorite, brought his one-off Cadillac Silverstone Healey. By 1950 the new Cadillac OHV V-8s were world-beaters. A gaggle of Cadillac Allards would attend, including those of Chicago’s Fred Wacker, and MSCA member Bob Grier, driving the ex-Sydney Allard car which had recently placed third in the Le Mans 24 hour. Two new Ferraris were driven by Bill Spear and James Kimberley. Sam Collier, whose brother Miles had won the previous year, was entered in Cunningham‘s open-wheel 166 Ferrari. John Fitch, who later became the first American member of the official Mercedes-Benz team, brought a special of his own making. Veteran driver Bill Milliken was at the wheel in a still formidable Bugatti Grand Prix car.

As the weekend approached, insiders were speculating that any one of eight drivers could be the potential winner. Many thought that Englishman Tommy Cole and his hot Cad-Allard was the one to watch. A dark horse was MSCA member Erwin Goldschmidt with his beautifully prepared new Allard.

The Motor Sports Club entrants, however, had a hurdle to overcome. As a compromise with the SCCA, nonmembers were eligible to run in the preliminary Seneca Cup race, only advancing to the premier event, the Grand Prix, if they finished in the top three in the preliminary.

Goldschmidt had experience with fast cars before the War. He was the son of Germany’s leading banker, who had had the foresight to leave the Third Reich in its early days, and moved to England where Erwin subsequently attended Oxford. Immigrating to America, Erwin served as an officer in the U.S. Army with assignments behind enemy lines during World War II. Despite a successful career as a Wall Street insurance broker, he faced prejudice and was blocked by some elitist SCCA members for admission to their club.

Relegated to the preliminary race, Goldschmidt inquired moments before the start of how high he had to place to qualify for the Grand Prix. He finished second to Phil Waters in Cunningham‘s Cad-Healey. According to the rules, he then started last on the grid for the Grand Prix.

The Grand Prix fulfilled its promise as a thrilling race. Tommy Cole jumped into the lead with his powerful Cadillac Allard. He was closely followed by Sam Collier in the smaller 2-liter Ferrari, who appeared determined to repeat his brother’s prior year victory. Early on, Cole slid off the course. A short time later Sam, now in the lead, skidded on loose gravel catapulting the Ferrari end over end into the adjoining hayfield.

Sam died as a result of his injuries and American Road Racing abruptly came of age. What had been considered an enjoyable pastime was now recognized as the high-risk sport it was. Sam and his brother were well-loved racing pioneers, having competed at LeMans and elsewhere before the War.

Milliken in the big Bugatti briefly assumed the lead, to be passed almost immediately by Goldschmidt who, having started last, continued on to take the chequered flag. Briggs Cunningham placed second, his third in a row runner-up finish at Watkins Glen.

Some wags said Goldschmidt was an ungracious guest; having been invited, he had the bad manners to take home the prize. Be that as it may, he was not invited back the next year to defend his victory.

During the winter of 1950-51, the powers in the SCCA successfully lobbied the village of Watkins Glen, over the strenuous objections of SCCA stalwart Miles Collier and race organizer Cameron Argetsinger, to return to closed club racing.

The banner of international racing in the U.S. was fortunately picked up by Sebring, Florida, which brought world-class sports car teams to America for the next decades. It was not until 1958, after Argetsinger had rejoined the Watkins Glen organization, that its event was restored to the international calendar, ushering in a 20-year successful running of the US Grand Prix.

The Father of American Road Racing

Cameron R. Argetsinger was a visionary who could make things happen. He had a passion for fast cars and is remembered as an outstanding driver. In 1948, at Watkins Glen, he conceived, organized, and drove in the first post-war road race in America. He brought full international races to Watkins Glen in 1958 and, beginning in 1961, was organizer and race director of the Formula One United States Grand Prix. Formula One enjoyed a successful run of 20 years at the Glen circuit.

He was subsequently executive director of the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) in the 1970s. He later served as commissioner for the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) in the 1980s. A graduate of Cornell Law School, he practiced law for 48 years. Retiring from the law in 2002, he was president of the International Motor Racing Research Center until 2007. In 2005, Watkins Glen International honored Argetsinger’s legacy by titling the Indy Racing League winner’s trophy the “Cameron R. Argetsinger Trophy,” a prestigious sterling-silver cup.