July 11th and 12th, 1970 saw the World Sportscar Championship return for the third race of the year in the United States. Watkins Glen would host the Six Hour endurance race on Saturday and the Can-Am race on Sunday making it a double-header for some of the teams and drivers.

Porsche came into the weekend on a roll, having already clinched the Manufacturer’s Championship and having recorded their first overall victory at Le Mans. Ferrari had a poor race at Le Mans and hadn’t been close to a victory since Monza in late April. John Wyer’s JWAE/Gulf-Porsche team had a truly disastrous race at Le Mans and were looking to regain the dominant form they had shown most of the season.

Early on in practice, Jo Siffert was very unhappy with his Gulf 917 according to Ermanno Cuoghi in his book, Racing Mechanic: “Siffert was not happy with his car, it was just no good compared to Pedro’s. So we put Pedro’s car in one flat concrete bay and take all the suspension geometry readings off that car. Then we push Siffert’s car on the same spot, check everything out – especially bump and rebound settings- and it was quite a long way out. So we put Siffert’s car in exactly the same trim and Siffert was very happy with that car.” In Ian Wagstaff’s book, Porsche 917 – Owner’s Workshop Manual, mechanic Alan Hearn confirmed that bump steer (and toe-in) was critical on the 917 and something the JWAE mechanics worked on very carefully when setting up the cars in the workshop at Slough. At Watkins Glen, the team experimented with a revised rear fender shape to better accommodate 17-inch rear wheels. They also used special 10.5-inch front wheels to work better with revisions to the front suspension with reduced off-set. Although the track surface was new, it was breaking up in places so the team chose Firestone intermediate tires.

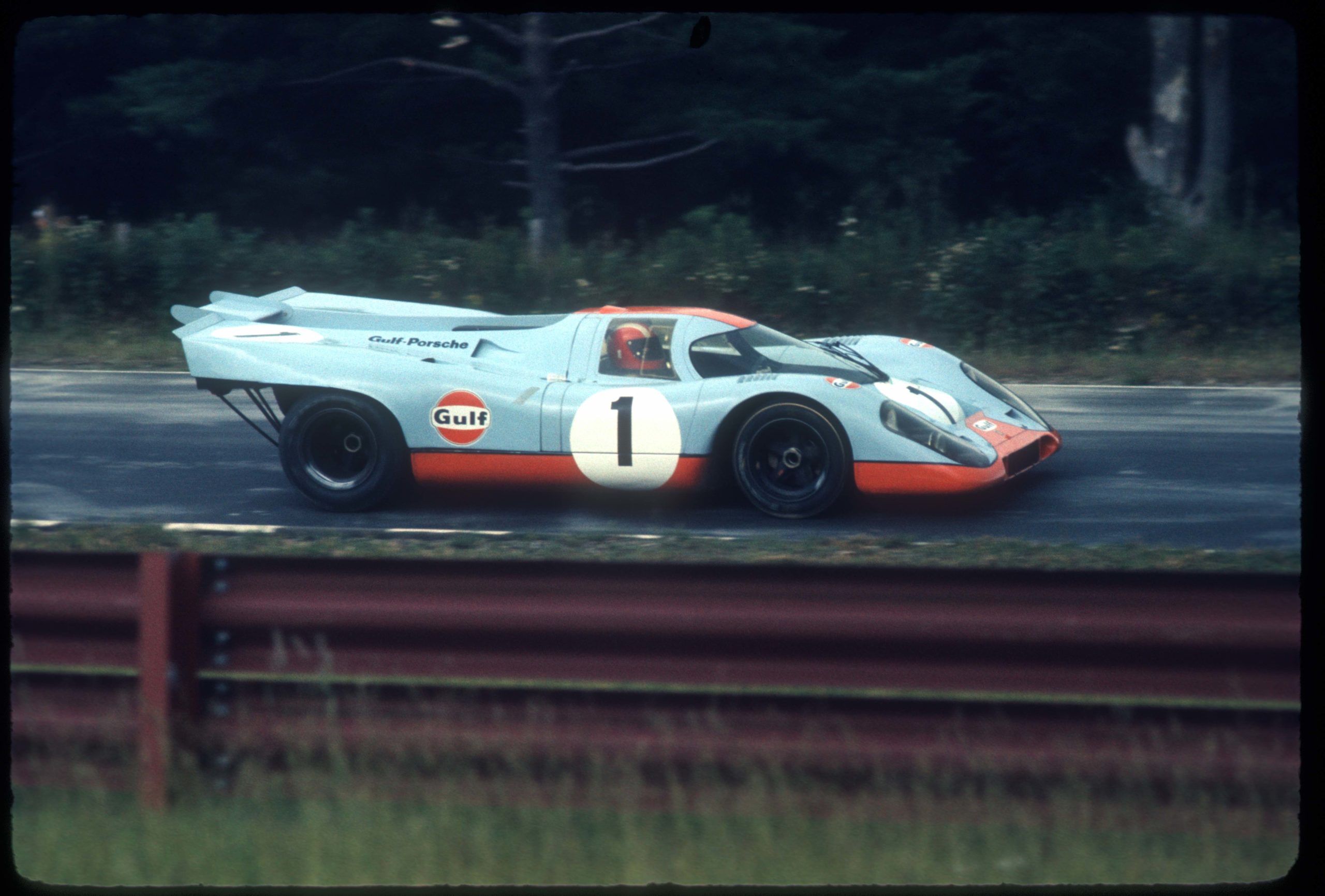

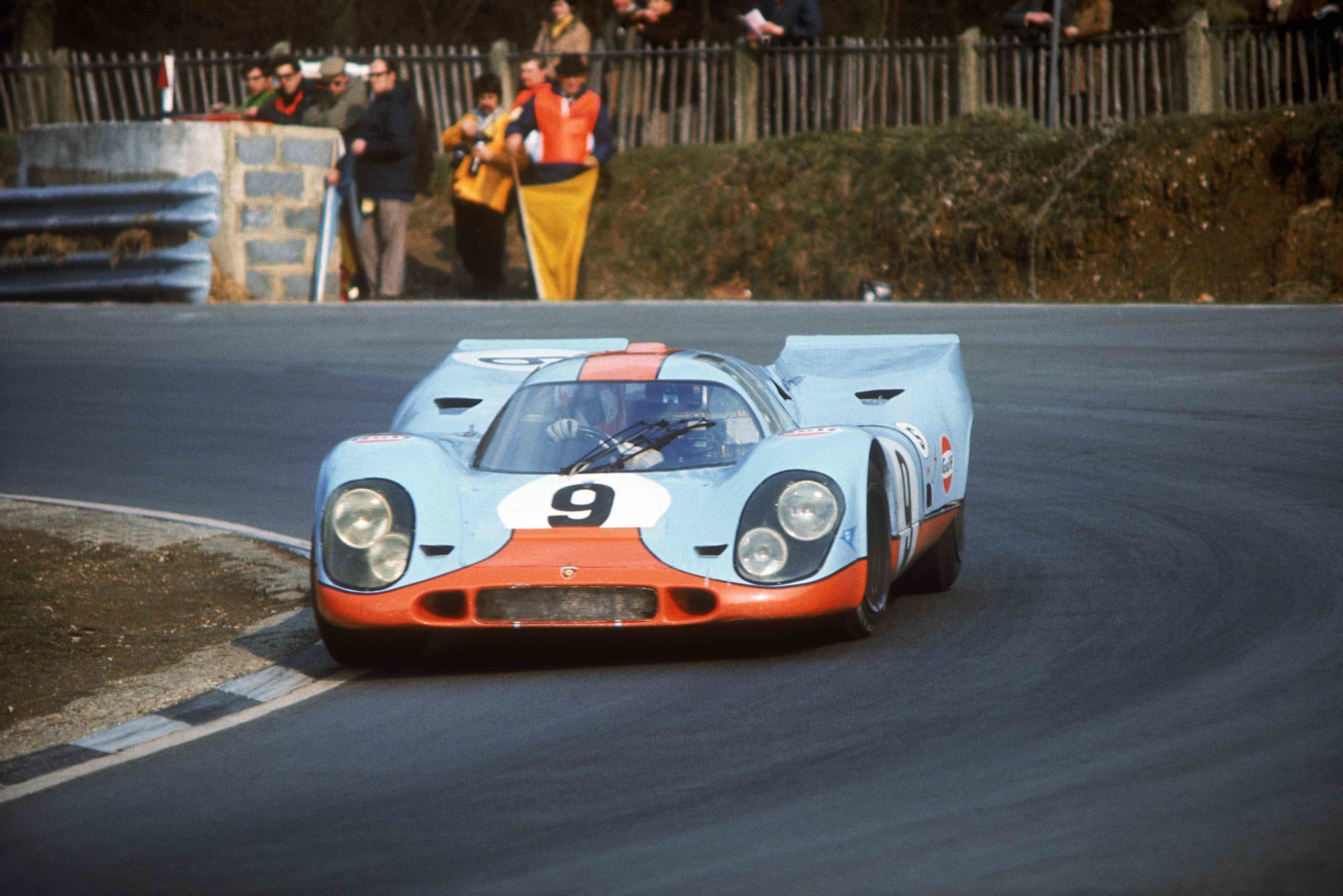

Jo Siffert in 917-014, Watkins Glen Six Hour Race. Photo: Porsche Archive

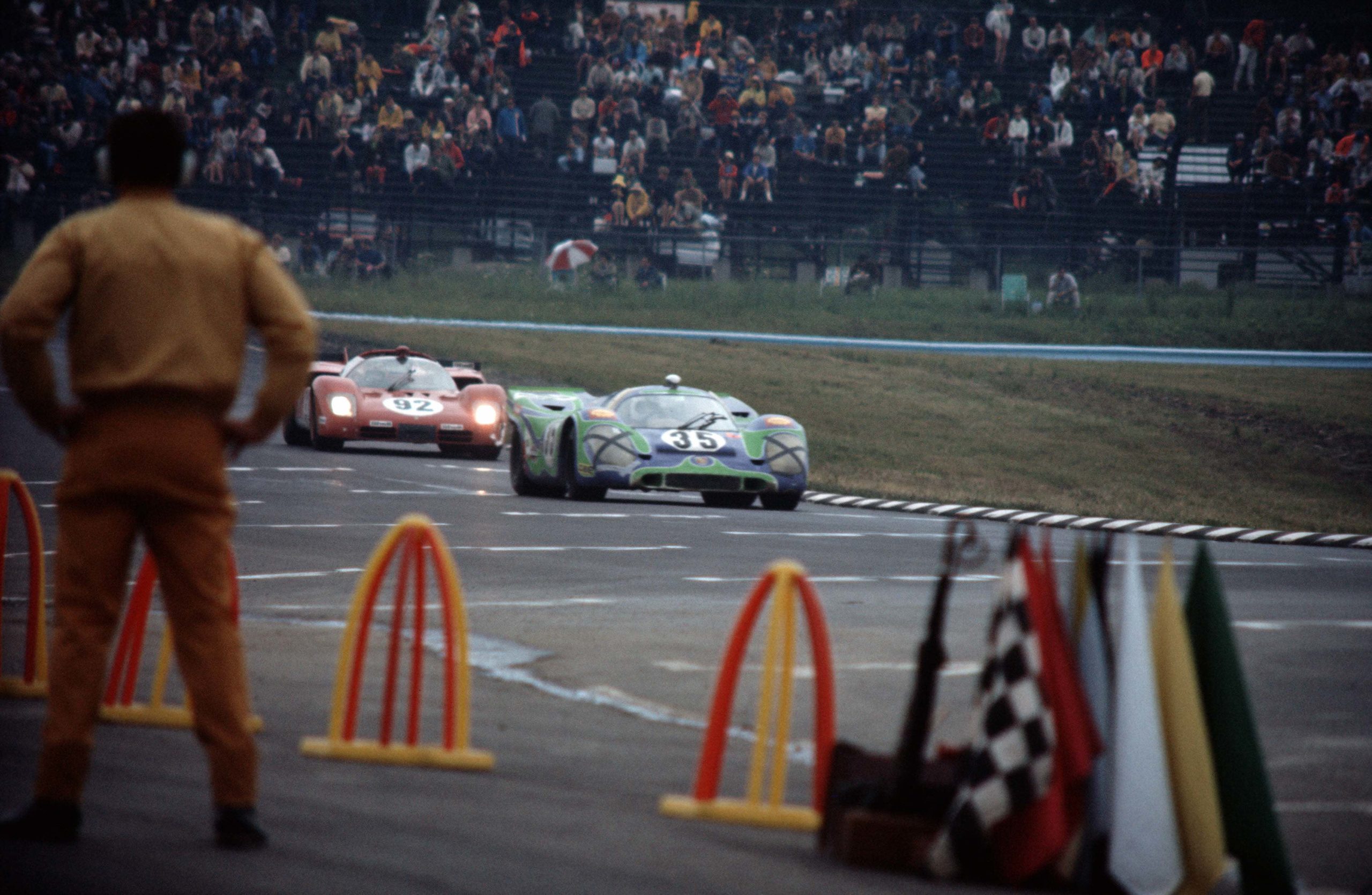

Ultimately, Siffert took pole position for the Six Hour, just three-tenths of a second faster than one Mario Andretti in a Ferrari 512S and Pedro Rodriguez in the other Gulf 917. Jacky Ickx and Peter Schetty were fourth fastest in the other factory-entered Ferrari 512S, followed by three more Porsche 917s. Larrousse and van Lennep were fifth fastest in the Martini entry (painted in psychedelic ‘Hippie’ colors). Sixth and seventh were the two Porsche-Salzburg 917s, Richard Attwood driving with Kurt Ahrens and Vic Elford paired with Denis Hulme. Jo Bonnier’s Lola T70 was eighth fastest with co-driver Reine Wisell.

After the rolling start which was standard at the races in America, there was quite a tussle at the first corner as Siffert and Mario Andretti touched, Siffert nearly spinning. Andretti led at the end of the first lap in the Ferrari, but Siffert passed for the lead on lap three. Siffert then led the race with Rodriguez closing in and passing just before the first fuel stop. There was light rain at the one hour mark and Siffert apparently had a misfire due to the rev limiter re-setting itself so it was disconnected at the first fuel stop.

Early in the race, Rodriguez had been flashing his lights to warn back-markers of his approach, but accidentally switched off a fuel pump (an easy mistake to make according to Alan Hearn, given the proximity of the fuel pump switches to the light switch). Realizing his mistake, Pedro then got back up to full speed and managed to claw his way back to the front. He actually got into the lead by lap 35, perhaps roused by his own error. He lost the lead to Siffert on lap 50 but gained it again on lap 53.

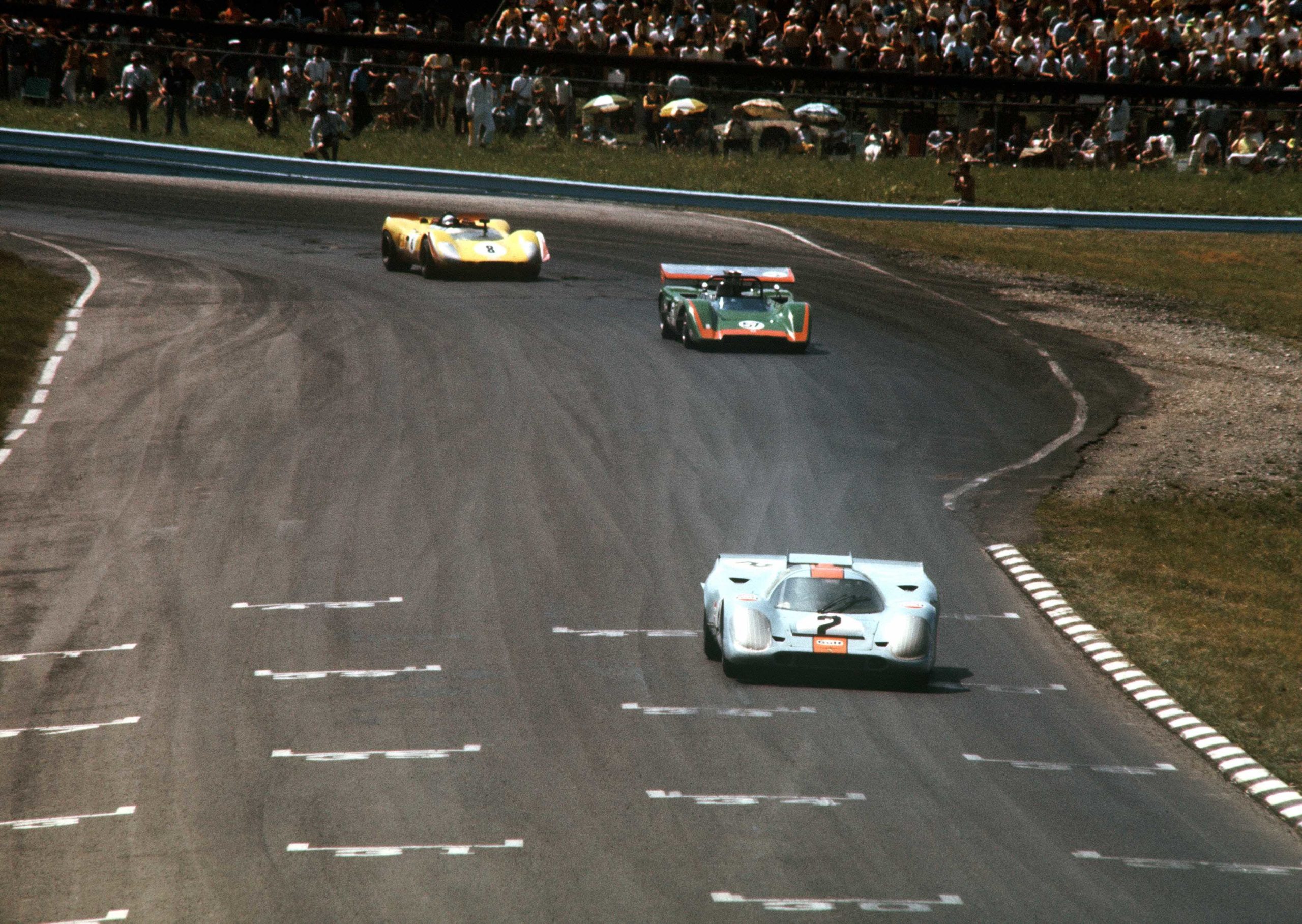

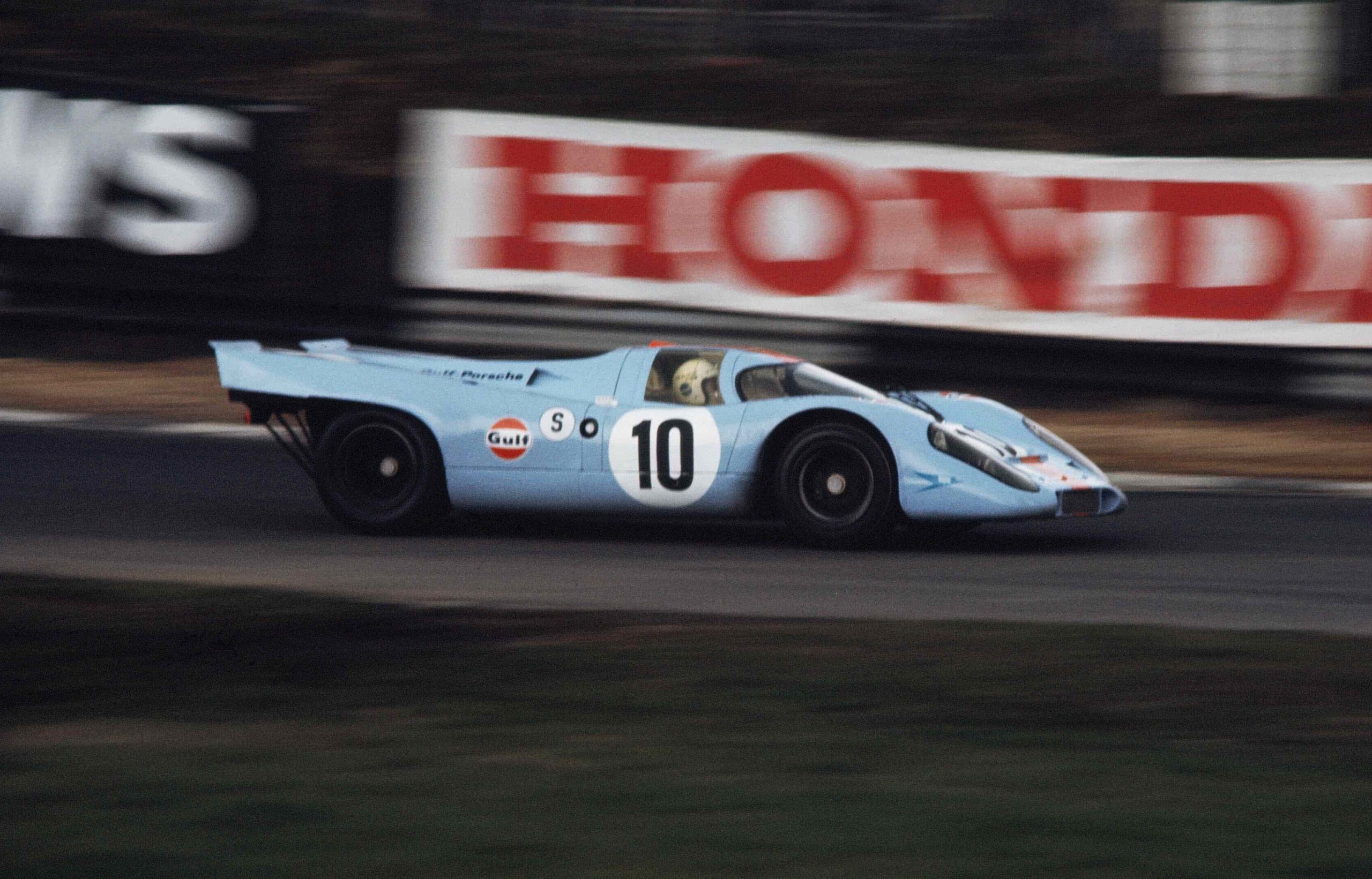

Rodriguez hounding Siffert in the Gulf-Porsche 917s. Photo: Porsche Archive

Rodriguez and Siffert then had a coming together around lap 100. This one was quite a bit more substantial than the touch at Spa earlier in the year. Pedro was approaching to put Jo a lap down. Siffert was not inclined to give way and when Pedro tried to swing by, Siffert clouted Rodriguez’s car, leaving a large tire mark on Chassis 016’s driver side door. In the film A Year To Remember, John Wyer stated that Siffert was trying to pass slower traffic and may not have seen Rodriguez coming up behind him. Perhaps Wyer was making an excuse as it seemed the simmering rivalry was now on full boil and the wheel banging and paint-swapping caused a flat tire for Siffert.

At the pit stop for a driver change, Ermanno Cuoghi and the Gulf mechanics made a quick repair to the damaged door on Rodriguez’s car. During the middle part of the race, Siffert’s co-driver, Brian Redman regained the lead and in a see-saw battle, Redman and Siffert then led from lap 105 to 160. However, when Rodriguez got back in the car, he put on his usual charge, as the situation demanded and took the lead on lap 161.

The wheel-banging incident may ultimately have cost Siffert and Redman a chance to win as their oil tank developed a leak after Redman had passed Kinnunen for the lead on lap 204. The oil tank was located on the left side of the car where the collision occurred. The tank repair put Siffert too far behind at a critical part of the race. Pedro took the lead from the Gulf sister car again on lap 211 and held it until the end. After 308 laps, Rodriguez was in first place by 44 seconds over the sister Gulf 917. Although Kinnunen only drove 51 laps to Rodriguez’s 257, his average lap time was recorded as four-tenths faster than Rodriguez in the JWAE race datasheet. Redman’s average lap time was only four-tenths slower than Siffert and given the variables of weather and traffic in a six-hour race, it shows that the nominal #2 drivers were highly capable behind the wheel.

Ignazio Giunti, Ferrari 512S versus Gijs van Lennep in the Martini-entered Porsche 917. Photo: Porsche Archive

Andretti and Ignazio Giunti held on to finish third, three laps down in their Ferrari 512. Jacky Ickx and Peter Schetty were fifth for the Ferrari factory. The Ferraris were hampered during the race by problems with their fuel systems. The Porsche Salzburg 917s finished in fourth and sixth places, Attwood ahead of Elford. This was the third of three wins in 1970 for 917 Chassis 016, which had won at Brands Hatch and Monza in April. The Watkins Glen Six Hour race was the closest head-to-head battle of the 1970 season between the Gulf teammates.

Jackie Stewart in the Chaparral 2J, Chris Economaki in front of the car. Photo: Kathie J. Meredith Collection/IMRRC

On Sunday, the Can-Am race was notable on a number of fronts. At the top of the list was the presence of reigning F1 World Champion, Jackie Stewart, driving for Jim Hall in the brand new and radical Chaparral 2J. This very early attempt at ground effect used an auxiliary two-stroke snowmobile motor to drive two fans at the box-shaped rear of the car. The fans sucked the air from under the car and kept it glued to the road. Lexan ‘skirts’ provided a seal under the car to maintain the suction effect. Problems with debris from areas of the track breaking up would hamper the auxiliary motor and fan drive during the event which started with practice on Wednesday. Stewart also admitted to having a learning curve with left-foot braking in the two-pedal, automatic transmission Chaparral. As far as the handling was concerned, Stewart enthused: “Adhesion is second to none, and is like comparing the road-holding of a touring car to that of a Formula One machine.”

The Gulf team entered their three 917 coupes in the Can-Am race. Although lacking the maximum power of the big-block Chevrolet-powered cars, the endurance racers performed quite well. Participation allowed the drivers to compete for significant prize money and Siffert would put on a great driving display. The final results were even more impressive considering that Siffert and the other Group 5 runners had to pit for fuel while the Group 7 Can-Am cars could go the whole distance without stopping.

A big crowd, stated at 70,000, saw Denis Hulme sit on the pole alongside Dan Gurney in the other McLaren M8D. This being the third race of the Can-Am season, the team were still adjusting to life without the founder, Bruce McLaren, who had been killed in testing in April. On Saturday evening, Hulme’s car was changed down to a 430 cubic inch Chevy from the regular 465 due to concerns about cooling. Stewart was third on the grid in the Chaparral with Peter Revson fourth in the Lola T220. Gurney and Revson stayed with the larger Chevy engines for the race. Mario Andretti was fifth fastest in his 5-liter Ferrari 512S. Lothar Motschenbacher was sixth fastest in an M8B with Jacky Ickx seventh for Ferrari. With all the endurance cars entered, the field for the Can-Am was an Indy-size 33 cars.

At the start of the race, Revson passed Stewart for third and held it until lap four when Stewart vacuumed his way back to first place of those chasing the McLarens. He was able to stay in close touch with Dan Gurney until lap 14 when the Chaparral came in for a long pit stop due to vapor lock. After seven further exploratory laps, the car was retired with near complete loss of brakes. Stewart did set fastest lap at 125.86 mph average speed, winning a $1000 bonus. Revson held third place until his oil pump drive belt failed. Gurney maintained second position, even with a black flag stop for passing under the yellow, but then had two lengthy stops with the engine overheating. Dan would soldier on to finish ninth.

Pedro Rodriguez, 917-016 in the 1970 Watkins Glen Can-Am. Photo: Porsche Archive

Pedro Rodriguez started 10th and moved up steadily, eventually running in fourth place. However, he missed a gear and dropped out with a blown engine on lap 32. It was the only time that Rodriguez fell victim to the 917’s well-known Achilles’ heel. In The Certain Sound, John Wyer recounts talking with Bob Corn of Ford Engineering Research regarding the problem of 917 over-revs wrecking the valve train. Corn advised that given the relevant data, a valve spring could be designed that would give a greater margin of safety. JW states that he reported this to Porsche’s Ferdinand Piech who “brushed it aside. It was the typical Porsche reaction to NIH (not invented here).” This doesn’t speak to the issue of the rev limiter itself not being able to act quickly enough.

Siffert had two spins while avoiding slower cars but at one point he was within 10 seconds of Hulme and “in some danger of winning the race” as John Wyer said before being balked by slower traffic. As Wyer also remarked in A Year To Remember, Siffert had to “motor over half of New York State” in one incident! Late in the race Hulme was slower than normal due to high coolant temperature and problems with the track surface that limited the power application for the big-block cars. Track debris was partially blocking the cooling system in his McLaren. Hulme was also suffering from still-painful burns on his hands from an incident at the Indy 500. Given the heat, his hands and difficult track conditions, he was quoted as saying the race was “the toughest I’ve ever run.” At the finish, Siffert in 917 Chassis 014 was only 28 seconds behind the McLaren. John Wyer called it one of the best races of Siffert’s life and since Jo (ever the wheeler-dealer) won more money for finishing second than Pedro had for winning the day before, he was very happy. Siffert won $9000 for second place plus the $1000 BOAC ‘Man of the Race’ bonus.

Jo Siffert in the Gulf-Porsche 917. Photo: Kenneth French Collection/IMRRC

It should be noted that on a rough day for the regular Can-Am campaigners, the Porsche-Salzburg 917s, sponsored by Porsche-Audi, finished third and fourth (Attwood ahead of Elford). Since 917 Chassis 015 was on hand at Watkins Glen as the Gulf T car, it could be assigned to Brian Redman for the Can-Am race. Redman finished seventh after being delayed by a right rear puncture on the 60th lap. 015 wore race number 6 with the orange greenhouse livery. In fact, the Group 5 endurance racing cars finished in second through seventh place including Mario Andretti, fifth for Ferrari and Gijs van Lennep, sixth in the Martini 917.

Regarding the Chaparral 2J ‘sucker’ car, author Karl Ludvigsen noted in Excellence Was Expected that Porsche’s Dr. Bott took the occasion to remark that Porsche had considered reversing the direction of the 917’s cooling fan to create the same effect. Porsche rejected the idea due to concerns about sucking dirt and debris into the engine area, as well as the problem of bumps on track changing the suction effect. It was also thought not to have any applicability to Porsche’s road cars. Since racing came under the general category of Research & Development, this was always a significant consideration for Porsche.

Watkins Glen was the 16th consecutive Can-Am victory for McLaren and they were getting ready to debut the M8E a bit later in the 1970 season. The JWAE-Gulf team would go on to win the final race of the World Sportscar Championship in Austria, making it seven wins for Gulf-Porsches in the ten race series for 1970.

Special thanks to Jenny Ambrose of the IMRRC for assistance with research materials and photos for this article.

April 12, 1970, was the date for one of the most famous endurance sports car races. The race was run partly in heavy rain and became a showcase for one of the great car and driver combinations in motorsport history. Mexican driver Pedro Rodriguez and his Gulf-Porsche 917 thoroughly defeated the opposition in one the best drives of his storied career.

Pedro Rodriguez with JWAE Team Manager, David Yorke, during practice for the BOAC 1000 Km at Brands Hatch in 1970. Photo: Porsche Archives

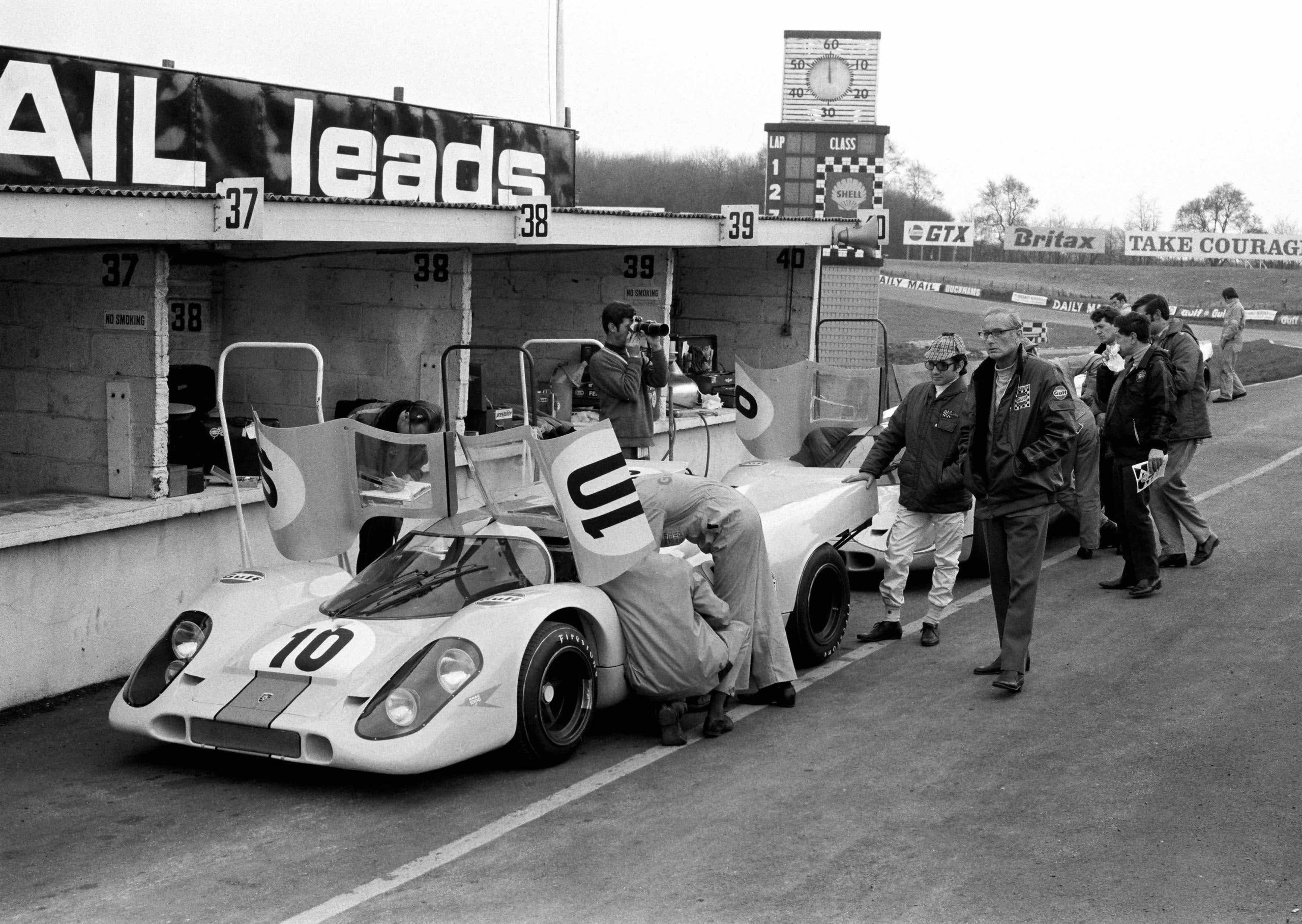

In contrast to the race, the weather was dry for practice and qualifying. Chris Amon put his Ferrari 512 on the pole, with Jacky Ickx second fastest, showing that Ferrari was competitive on pace after having won the previous race at Sebring. For the Gulf 917 team of Rodriguez and Leo Kinnunen, there was a gearbox problem in practice. The team elected to move the car to the grass area ahead of the pits for more room to work (the pits being congested and the paddock too far away). The problem was with the linkage and connection where it went into the gearbox. Pictures show the team around the car with the right side transmission cooling duct removed. Rodriguez ultimately qualified seventh with Jo Siffert and Brian Redman fifth in the other Gulf 917. Vic Elford was third in another 917 for Porsche-Salzburg. The 3-liter Matra MS 650s were fourth and sixth in qualifying. The top seven cars were all within 1.4 seconds of each other on lap times. The rather short, twisty Kent circuit was not ideally suited to the 917, a car designed for high-speed tracks like Monza, Spa, and Le Mans. All the cars in the race wore special decals on the front fenders; a blue BOAC 1000 KM logo.

Jo Siffert in his Gulf-Porsche 917 during practice. Photo: Porsche Archive

Readers may notice that the Gulf 917s look a little odd in some photos from the race. The reason is that for part of the race, they ran on wheels that were only 9.5 inches wide in front, 12 inches at the rear. Firestone had recommended the narrow wheel approach to the Gulf team as it would make the cars easier to control in heavy rain. The Firestone wet tires were also thought to perform better than the Goodyears on the Salzburg Porsches, giving the Gulf team an additional edge. Ferrari ran on Firestone, so no difference there. JWAE Chief Engineer, John Horsman, noted that on lap 154, the team elected to change to intermediate versus full wet tires, the intermediates being the normal 10.5 and 15-inch widths.

Despite the gloom, a good crowd of 20,000 came out to see the biggest sports car race of the year in England. A cold (47 Fahrenheit/8 Celsius), steady rain fell in the hours before the race and right through the start. There was some debate among the officials about whether to start the race but Clerk of the Course Nick Syrett was determined to go ahead. An equally determined Vic Elford passed Chris Amon and Jacky Ickx in their Ferraris on the first lap, hoping for a few laps clear of the spray from other cars. Barrie Smith’s Lola T70 spun and crashed at the end of the first lap, at the start/finishing line. Smith was forced to start without regular rain tires on the rear because Goodyear ran short of tires in the needed size. It is possible that Pedro Rodriguez passed another car in the yellow flag area but also it is likely he was unable to see the yellow flag due to the spray. Most of the drivers agreed it was possible to have missed the flag the way it was initially displayed.

Porsche Archive candid of Pedro Rodriguez.

Syrett took over the waiving of the yellow and became upset with Rodriguez’s speed and proximity on the next two laps as the marshals attempted to move Smith’s car safely off track. He then elected to show Pedro the black flag, which Rodriguez ignored for two additional laps. Syrett then advised John Wyer that Pedro would be disqualified if he didn’t come into the pits. Pedro finally came into the pits (on lap six) on the signal from his team. In The Autobiography of 917-023, author Ian Wagstaff quoted Rodriguez’s lead mechanic, Alan Hearn, on what happened next: “Pedro then came tearing down the pit road and I was assigned to open the driver’s door when he stopped. Syrett was hovering right behind me. As soon as I opened the door I could see from his blazing eyes that Pedro was not happy. Straight away, Nick dived in the cockpit with his head well down and proceeded to have a right go at him for dangerous driving, a real tongue lashing. Pedro just kept staring straight ahead, not looking at Syrett until he was finished, which took about 20 to 30 seconds. I could see he was fuming. All this time the engine was running. As Syrett stepped away from the car I quickly shut the door. Pedro revved like mad, spun the rear wheels and shot off down the pit road at a very rapid rate. We were lucky we didn’t get our toes taken off…..”

Syrett was an imposing figure, standing over six feet tall and well over 200 pounds. All the witnesses agreed that Pedro sat impassively, but with a building fury, not making eye contact while Nick gave his finger-wagging lecture. Pedro later told John Wyer that he did not see the yellow flag and did not feel he was driving unsafely. After the lecture, Pedro rejoined the race almost a full lap behind the leaders. Syrett had unknowingly set the stage for one of the all-time great drives but he also told Wagstaff that the “telling off” continued after the race on the lap of honor!

Vic Elford led the early laps until he was caught and passed by another acknowledged rain-master, Jacky Ickx. However, Ickx had to pit on lap eight with wiper problems. Rodriguez was already on a furious charge through the field and was up to third place on lap 15. Amon’s Ferrari was running in second place and Chris forced his way past Elford on lap 16 to lead briefly. Pedro passed Elford on lap 18 and set off after the Ferrari. On lap 20, Pedro charged out of Clearways, pulling alongside at start/finish and splashed by Amon in the Paddock Hill bend for the lead.

Siffert was delayed on lap three by a puncture of the left rear tire. Jo and Brian eventually held station, alternating between second and third place until Redman crashed on lap 177. The accident happened at Westfield bend as Brian was pushed off the road by Amon’s Ferrari. Because the car hit a bank while traveling backward, the rear bodywork was pushed over the top of the car, trapping Redman inside. The marshals eventually extricated the driver who made his way back to the pits, wet and muddy, from the farthest point on the track. Brian had expressed some concerns about the safety aspect of the 917. He related the story of this accident and subsequent discussion with Porsche’s Dr. Bott to the writer in 2009:

“I was lying second (when) I got tapped by Chris Amon in the Ferrari 512 and it spun me. I went into a banking and I couldn’t get out because the tail came up over the roof. Anyway, I’d been complaining to Porsche engineering, to Herr Bott in particular, about why did Porsche build these aluminum space frame chassis when everybody else had monocoques or semi-monocoques. The Kurt Ahrens car had broken in half across the cockpit, the John Woolfe car had broken in half across the cockpit. So, when I got back to the pits, it’s raining, I’m muddy, and Herr Bott says: ‘Brian, are you okay?’ I said ‘yes, thank you, Herr Bott.’ He then said, ‘Now you see the 917 is a very good car to have a crash in!’

The possible consequences of a fire in this type of crash may have been lost on the soggy Dr. Bott at that moment. Brian’s references are to the fatal crash of John Woolfe at Le Mans in 1969 and Kurt Ahrens’ crash at the Volkswagen test track just six days before the Brands Hatch race.

Leo Kinnunen in 917-016 during practice. Photo: Porsche Archive

By lap 50, Rodriguez’s lead was over a minute and a half on the field. By the two-hour mark, he was able to put Elford a lap down for the first time. Both Elford and Rodriguez had spins of their own in the appalling conditions but were able to get back on track. Approaching three and a half hours, Rodriguez stopped for the mandatory driver change, Kinnunen taking over for 38 laps. After about four hours, the rain eased off and the track began to dry some. Like Rodriguez, second-place driver Elford drove nearly six hours out of a 6 hour, 45-minute race. Elford’s co-driver, Denny Hulme, was never a fan of driving in the wet and he gladly deferred to the ex-rally man. For the record, the winning car (917 Chassis 016) covered the 235 laps in 6 hours, 45 minutes, 29.6 seconds. In all, Rodriguez lapped the field five times. John Horsman noted in his book that the fans delighted in Pedro’s masterful work, staying to the end of the race despite the miserable conditions.

Pedro Rodriguez sliding through the wet and gloom of April 12th, 1970. Photo: This image was graciously provided by the Mike Hayward collection, a specialist library of classic British motorsport photographs and is available for purchase as a print here: www.mikehaywardcollection.com.

Many superlatives have been offered over the years about Rodriguez’s drive. David Hobbs, who watched from the Gulf team pits was on hand as a reserve driver in case Brian Redman didn’t make it back from the Le Mans test weekend in time for the race. Hobbs recalled: “There was never anything similar to Pedro that day in Brands Hatch; it was the greatest performance I’ve seen.”

Brian Redman said: “Pedro, no doubt, became someone different after the incident in Brands Hatch. From then on, his stature in the eyes of others grew impressively. We all knew how good he was, but that day, the whole world took notice.”

Vic Elford wrote: “Both Jacky Ickx and I were acknowledged wet-weather drivers, but neither of us had an answer to Pedro that day. He simply trounced everyone.”

From Richard Attwood: “I would challenge anyone to drive a car as fast as Pedro did that day. Jim Clark, had he been alive, or any other you could name, in fact, nobody could have equaled Pedro that day.”

In 2013, Alain de Cadenet, who drove a Porsche 908 in the race, wrote: “No racer, before or since, could fail to have felt proud of Pedro that day at Brands.”

John Horsman in 2014 said simply: “It was the right car on the right tires with the right driver.”

Ian Wagstaff quoted Rodriguez’s companion Glenda (Fox) Foreman: “I think Pedro was almost in awe of himself that day…”

Interestingly, the Gulf Team headmaster, John Wyer, thought that Pedro’s performance at the Osterreichring in 1971 surpassed the more famous Brands Hatch race. In his book, ‘The Certain Sound’, he said the race in Austria was “without question” the greatest race Pedro ever drove. Perhaps the spectacle of racing in the rain (which became the title of John Horsman’s book) at Brands Hatch better captured the popular and historical imagination. Also, there is a good film documenting the 1970 race at Brands Hatch – enjoy the 50th anniversary and see for yourself: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0YCGF3ncEY

Thanks to Porsche Archive for the use of their photos. Special thanks to Mike Hayward for the use of his photo from www.mikehaywardcollection.com. Jay Gillotti’s book, “Gulf 917” is available from Dalton Watson Fine Books – www.daltonwatson.com.

Porsche was pretty good at keeping secrets. Before the 917 was shown at the Geneva Salon in March of 1969, even the factory’s team drivers were unaware of its existence. Porsche had designed and built the first car in near-complete secrecy over the previous eight months. Once the car began testing and appearing at races, it was obviously fast. Jo Siffert put a 917 on the pole at its first race, the 1000 KM at Spa, but tellingly elected not to race it. Siffert and Brian Redman went on to win the race in a longtail 908. By June, at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, it was no secret that the 917 had a serious handling problem. At high speed on the Mulsanne straight, it was wandering across the road. The high-speed bends were equally difficult. But in the race, Vic Elford and Richard Attwood employed some judicious driving to hold the lead for about 18 hours. They might have won had the transmission case not cracked allowing oil to flood the clutch.

Despite a continuing issue with instability, Siffert and Kurt Ahrens managed to take the first victory for a 917 at the final race of the Manufacturer’s Championship season. In the Zeltweg 1000 KM race in August, the 3.0-liter Cosworth-powered M3 Mirage was faster than the 917, but Porsche reliability and hard-driving prevailed. Two months later, Porsche returned to the Osterreichring at Zeltweg for a test session, determined to resolve the evil handling characteristics of the 917 once and for all. Meanwhile, Porsche had contracted with John Wyer’s Gulf-sponsored JW Automotive Engineering team to run the official factory cars in the 1970 Championship. The Zeltweg test would be the first with Porsche and JWAE personnel working together. While the Porsche engineers, Peter Falk and Helmut Flegl, concentrated on trying numerous shock absorber and spring settings (to no avail), Gulf team Chief Engineer, John Horsman, famously noted the lack of dead bugs on the tail surfaces of the test cars.

Jo Siffert takes the checkered flag at Zeltweg, August 1969 – Porsche Archive

The little gnats led Horsman to suspect the real problem was aerodynamic – lack of downforce over the rear wheels. In an inspired bit of shade-tree engineering, he worked with his mechanics, Ermanno Cuoghi and Peter Davies, to reshape the tail of the 917. Using sheet metal, tape, and screws, they extended the line of the tail from the top of the rear wheel arches to the top of the tail fins (already running nearly straight up). Finished overnight, the new tail was first tried by a skeptical Brian Redman on the following morning. Instead of coming in after the customary two laps with a grim shake of the head, Redman stayed out for seven progressively better laps. Returning to the pits, Redman stated simply and prophetically, “Now it’s a racing car……”

View of modified 917 tail, Zeltweg test, October 1969 – John Horsman Collection

By the end of the Zeltweg test, the 917 was fully five seconds faster per lap than it had been three days before. Even Ferdinand Piech, as head of R&D for Porsche and doggedly committed to minimizing drag on his race cars, had to approve of a new tail design. However, there was a huge amount of work to be done. The Porsche design team, led by Eugen Kolb, had to finalize the new tail shape and this included redesigning the rear window, creating a ‘tunnel’ in the upward sweeping tail for rear vision, and re-routing the exhaust pipes to the now-open area behind the rear wheels (the 917 originally had side exhaust outlets for the forward cylinders of the flat 12). This required new side pods as well. The new nose shape had to be finalized, including larger ducts and fender vents to improve brake cooling. All of this work was accomplished in a mere four weeks as there was another important test scheduled. The new version of the 917, now commonly referred to as the 917K, was scheduled to test at Daytona on November 19 and 20, 1969.

This test was kept highly secret and no photos were taken. Even Speedway employees were kept out of the grandstands and the infield. Attendees included Ferdinand Piech, Helmut Flegl, Peter Falk and Helmuth Bott plus a group of mechanics from Porsche. The Gulf team was represented by John Wyer, John Horsman, team manager David Yorke, mechanics Alan Hearn and Ermanno Cuoghi. Test drivers were Jo Siffert, Kurt Ahrens, Pedro Rodriguez, and David Hobbs. Pedro Rodriguez had signed to drive for JWAE and would have his first chance at the 917 during this test. David Hobbs was on hand as a tryout, potentially to co-drive with Pedro.

Artist conception of November 1969 Daytona test by Steve Jones – Steve Jones Scan 1 painting for “Gulf 917”

This was the first chance to test the finished version of the new tail at high speed, along with the other detail revisions (new nose shape, engine exhaust, rearview tunnel, etc.). Porsche also brought a long tail for testing but the drivers were not enthusiastic compared to the new ‘K’ tail. The activities combined specific testing, including tire comparison between Goodyear and Firestone, with simulated races or endurance runs. Testing was hampered by several on-track incidents. Ahrens had a tire failure that damaged chassis 012, requiring significant repairs. There is mention in sources such as Karl Ludvigsen’s Excellence Was Expected that Rodriguez was hit by a wind gust, causing a crash on the banking. However, John Horsman and Alan Hearn could not recall this incident specifically when consulted for my book, Gulf 917, and it is not mentioned in Walter Naher’s 917 Archiv.

On the second day, Hobbs missed a gear coming out of the infield and on to the banking. Finding second gear instead of fourth on the upshift over-revved the engine. In the glare of this intense test session with the Porsche personnel, the mistake likely cost Hobbs the job of partnering with Rodriguez for 1970. Porsche had already specified that Siffert and Redman would be the ‘factory’ drivers in one Gulf car (those drivers to be paid by Porsche). JWAE would have the choice of drivers for the other car (to be paid by Gulf). John Wyer had hoped to form what hindsight says could have been a ‘dream team’, pairing Pedro Rodriguez with Jacky Ickx. Ickx had played a prominent part in JWAE’s success from 1967 through 1969. To Wyer’s chagrin, Ickx signed with Ferrari for both Formula One and sports car racing in 1970. Wyer opined in The Certain Sound: “Probably one of his greatest mistakes.” This left the job to the relatively unknown Leo Kinnunen from Finland to co-drive with Rodriguez.

The Daytona testing led to a number of design and detail changes that would be incorporated into the race cars for the 1970 season. Cockpit heat issues led the JWAE team to reroute oil to the cooler through dedicated oil lines rather than using chassis tubes as originally designed. Dedicated oil lines also seemed safer than relying on chassis tubes to conduct the oil. Taper wear on brake pads was a concern as was general stability under braking. This led Porsche to rethink the design of the front wheel hub carrier. The test also resulted in several detail changes to the steering rack and the transmission. Rodriguez requested the steering wheel to be closer, so JWAE fabricated a 19mm spacer to be used in the 1970 races. Forward vision on the banking became a concern for the drivers and this led to the development of the D-shape roof window to help with this problem. Best lap times at the Daytona test were in the 1:47 range, about five seconds faster than the existing track record. Complete details of the Daytona test and follow-up work were published in Walter Naher’s book, 917 Archiv.

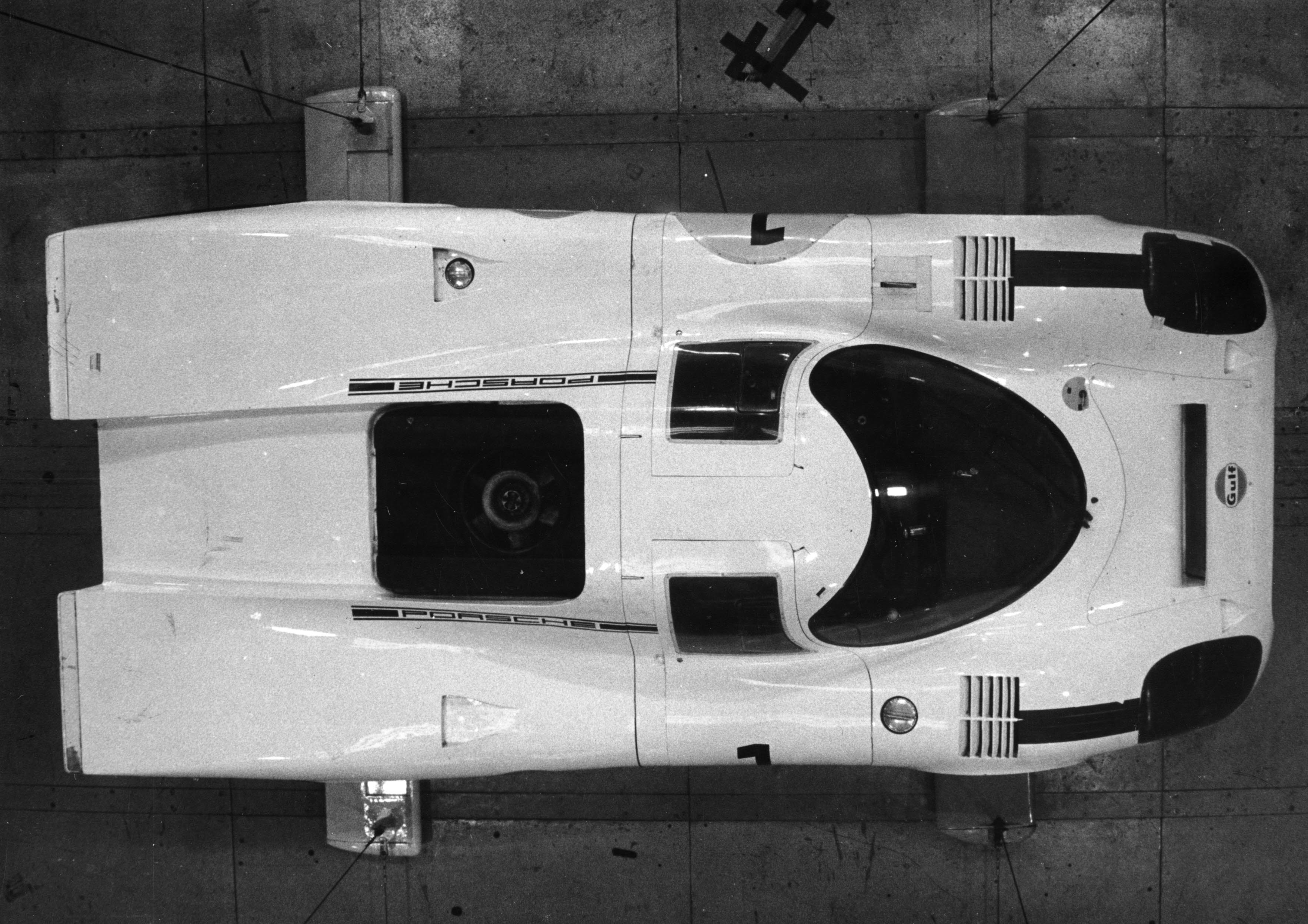

Although no photos exist of the Daytona test, we do know what the cars looked like when run in Florida. Upon their return from Florida, one of the cars (Chassis 011) was used for wind tunnel testing at the University of Stuttgart facility. There had not been time to check the new nose and tail prior to the Daytona test. However, the December 1969 wind tunnel review confirmed acceptable drag and downforce readings. The increase in aerodynamic drag resulting from the new ‘K’ tail was partly offset by the reduced weight of the rear bodywork. No further changes were made to the body shape prior to the 1970 Daytona race except for the addition of the roof window.

Chassis 011 in the wind tunnel after returning from Daytona, December 1969 – Porsche Archive

The Daytona testing largely finalized the form and specifications for the 917 that JW Automotive would start with for the 1970 racing season. How well did it start? The Gulf-Porsches would finish first and second in the 24 Hours of Daytona with the winning car setting a distance record that stood until 1987. Given the level of documentation throughout the 917 program, it remains surprising that no photo exists of the truly secret Daytona test.

The 50th anniversary of Porsche’s 917 has triggered a wave of interest and appearances for the cars. Porsche has led the way with a significant display at its museum. The centerpiece of the ‘Colours of Speed’ exhibit is the newly-restored 917 Chassis 001.

Ferdinand Piech reveals the 917 at the Geneva Salon. Photo: Porsche Archive

Chassis 001 was the first 917 to appear in public. According to Walter Naher’s authoritative book, 917 Archive, there is no record of the exact date of completion, but it was likely March 10, 1969 allowing just one day for transportation to Geneva. The car was unveiled at 3:09 PM local time on March 12 in the Swiss Auto Club booth at the Geneva Motor Show press day. The original body shape may now look slightly dated but it must have been stunning to the assembled journalists. Looking similar to a longtail, 3-liter 908, but more purposeful and menacing, the real news was under the tail. Since the development of the 917 was a well-guarded secret, few could have guessed Porsche would be showing and offering for sale a Group 4 ‘Sports’ racer with an air-cooled flat 12 engine displacing 4.5 liters. The price was listed at DM 140,000. That was about $35,000 or a little under $250,000 in today’s money.

Porsche competition manager Rico Steinemann made a brief statement before Ferdinand Piech, as head of R&D for Porsche and the father of the 917, removed the cover himself. Several of the Porsche factory team drivers were also present for the unveiling. Jo Siffert, Gerard Larrousse and Gerhard Mitter can be seen in the photos along with Vic Elford. Elford was particularly enamored of the 917, a case of love at first site. In his book, Reflections on a Golden Era in Motorsports, Vic wrote: “I fell in love with its curves and the sensation of power that emanated from it, even while it sat still and silent.”

Twenty-five Porsche 917s lined up for homologation inspection. Photo: Porsche Archive

Chassis 001 made its next appearance on April 21, 1969 in the forecourt of Porsche’s race shop in Zuffenhausen, first in line of course. The occasion was the homologation inspection of the initial run of 25 917s. As a Group 4 ‘Sports’ racer, the rules required that Porsche build 25 cars in order to race in the World Sports Car Championship. The FIA/CSI representatives (Delamont and Schmidt) duly reviewed the line-up with Ferdinand Piech and the Porsche team. 001 was then used for some testing duties in 1969. Walter Naher lists tests at the Nurburgring Sudschleife (May 14 with a short tail, engine damaged) and Weissach (in June, an extended wheel bearing test over 220 kilometers on the skid pad).

Chassis 001 in IAA Frankfurt Motor Show colors. Photo: Porsche Archive

Chassis 001 in Gulf announcement colors. Photo: Porsche Archive

In early September, chassis 001 was shown at the IAA Frankfurt Motor Show (International Automobil Ausstellung). The car was white with orange stripes, orange wheels and wore race number 3. The car was then painted in Gulf colors for the announcement of the partnership between Porsche and JW Automotive on which took place on September 30, 1969, at the Carlton Tower Hotel in London. After this press reception, the car was put on display at the Earl’s Court Motor Show. A discreetly small John Wyer signature appeared on the left front wheel arch. Although Herr Naher doesn’t list it, at least one photo exists showing 001 at the Jochen Rindt Motor Show in Vienna (in Gulf colors with a large Porsche badge on the nose). Likely this would have been in November of 1969. The Rindt event moved to Essen after Rindt’s death and continues to this day as the Essen Motor Show.

Historic Porsche display at Courtanvaux Castle. Photo: Porsche Archive

The next appearance was at Le Mans in 1970, but not for racing. Chassis 001 was part of a display of historic Porsche racing cars at Courtanvaux Castle. A 917 engine was also part of the display and at this stage the car still wore its 1969 Le Mans-style, longtail bodywork and Gulf colors.

In September of 1970, chassis 001 was converted to 917K bodywork. For the Paris Motor Show of October 1970 it was painted in red race number 23 Porsche-Salzburg livery to replicate the appearance of Chassis 023, the actual 1970 Le Mans-winning car. Herr Naher lists October 6, 1970 as the official date for 001 to be transferred to the Press Department as an exhibition car. It also appeared at motor shows in London, Brussels and Germany (Essen) during this period. In the spring of 1971 it came to the US for the New York Auto Show.

For many years it was thought that chassis 001 might have been re-numbered 009, possibly in preparation to replace the damaged chassis 009 after the Sebring race in 1971. There is no evidence currently to support this, however. The car remained in the Porsche Museum collection, standing-in for the 1970 Le Mans winner for the next 45 years. 001 came back to the US in 1998 for the ‘Double 50’ celebration at Watkins Glen, organized by Brian Redman. This event celebrated Porsche’s 50th anniversary as a manufacturer and the 50th for racing at Watkins Glen. Also in 1998 the car was shown at Laguna Seca during the Monterey Historic Races. The most recent appearance in the US was in 2015 at Rennsport Reunion V.

Chassis 001 at Rennsport Reunion V. Photo: Jay Gillotti

The restoration project began in January of 2018 with a technical assessment that established feasibility and the originality of many components. Disassembly began in February of 2018. 3D scanning and CAD technology along with the original factory drawings were used to recreate the nose and tail. The frame for the 1969 long tail also had to be recreated along with the rear axle kinetic lever system. This was designed to actuate flaps moving up or down depending on the direction of a turn. As ‘moveable aerodynamic devices’ the flaps were outlawed after the 1969 Le Mans race. The roof section, windscreen and doors were original and did not require rebuilding. The new body was completed and painted by January of 2019, leaving only a few weeks to reassemble the car. The Porsche Newsroom article on the restoration can be found at: https://newsroom.porsche.com/en/2019/history/porsche-917-001-disassembling-restoration-museum-17525.html.

The restored chassis 001 poses with Concorde 002. Photo: Porsche Archive

Prior to the opening of the new exhibit, Porsche debuted the restored Chassis 001 at the Retro Classic show in Stuttgart. This was in March, almost 50 years to the day since the car was first shown in Geneva. Porsche then took Chassis 001 to the Goodwood Member’s Meeting for exhibition runs along with four other 917s. While in England, it posed with Concorde 002, also celebrating a 50th birthday, at the Fleet Air Arm Museum. The YouTube video link (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vqBA1JIJ5l4) shows 1970 Le Mans-winning driver, Richard Attwood, visiting with Concorde pilot Tim Orchard. ‘Colours of Speed’ runs until December 8th at the Porsche Museum and all the 917 fans in the US hope that Chassis 001 will make an appearance in the US sometime in the next few years.

-Jay Gillotti

Jay is the author of “Gulf 917,” a comprehensive history of the Porsche 917s associated with the JW Automotive/Gulf Racing Team. The book is available at www.daltonwatson.com.