For a guy who recently finished a book on some of the deadliest years of professional racing—and the safety revolution those years spawned—I felt strangely numb the day after Ryan Newman escaped from his finish-line crash at the Daytona 500. A brutal series of events, the crash included four different circumstances in a couple of seconds that could have potentially killed the driver.

The end of this Daytona 500 was like a near-death experience, except not your own. Once the thankful outcome became certain, there’s an aftermath. Relief comes first and before nagging doubts finally pass in one last shudder of horror.

On Tuesday the day after, I found initial relief in some thoughtful online comments plus the professional work of a couple of fellow commentators. Writer Ryan McGee and broadcaster Ricky Craven helped sum up that whole oddball process of a brilliant racing enterprise, invariably part ritual and part magic, turning into something else.

Those two summed up the nagging doubts that creep in when the close-to-the-bone nature of racing gets revealed and how the sport’s community of participants and fans face up to the reality of the mechanized, ritualized danger. Oh, there was plenty of standard stuff out there, too. Some expressed their doubts by criticizing the drivers—or NASCAR for how it operates the races on the Daytona and Talladega tracks. Some took it as an opportunity to express envy disguised as sarcasm because NASCAR’s stock cars and drivers are so popular compared to their own preferred style of racing.

In fact, the Daytona 500 requires each driver to make critical split-second decisions at sustained speeds of 200 mph every lap. If it becomes a race of cautions and attrition, well nobody complained in the years when only three or four drivers finished on the lead lap.

I felt lifted, and fully relieved, at the end of the day on Tuesday when I came across one road racing photographer’s Facebook post that was a funny take on his family members’ relative lack of racing knowledge. It underscored that everybody, not just race fans, were talking about Newman’s crash. (This was a particularly poignant as well as funny post considering the family has been fighting, successfully, alongside a teenage son in his battle with cancer.)

The potential for gut-wrenching outcomes have always been there in racing and will continue. Newman’s crash, for example, was a reminder of Sebastien Bourdais’s head-on collision with the barrier at Indy during qualifying for the 500 in 2017 at a speed of 227 mph. The difference was the French driver, who suffered a fractured pelvis and broken hip, remained conscious and alert afterward, immediately easing fears of the worst-case scenario. By contrast, it took almost a week for Newman to release a statement that he had suffered a head injury and would return to full-time status pending a medical clearance.

The replays of Newman’s finish-line crash will be repeated ad infinitum—because the driver survives to tell about it. I like this element, given that I wrote a book titled “CRASH!” containing voluminous research on how the safety revolution brought racing to the point where this kind of crash can be survived.

The safety revolution occurred across all the world’s major racing series. It started in Formula 1 with the death of three-time world champion Ayrton Senna in 1994. CART simultaneously began making major safety improvements after the injurious crash of two-time world champion Nelson Piquet during practice at Indy; CART became the first to mandate the HANS device prior to the 2001 season. The movement then came to NASCAR as a result of four driver deaths over a nine-month period, including Dale Earnhardt’s last-lap crash at Daytona. Given that these series operate in their own orbits and fans often do likewise, very few fully recognized how the safety revolution actually occurred. And how decisions in all three of these series helped make it happen.

The book is subtitled “From Senna to Earnhardt” for this reason. One could argue that their deaths—the great F1 champion from an errant suspension piece and Earnhardt from a basal skull fracture—during races watched by tens of millions of fans on live television were the two biggest events in motor racing in the last 100 years. After a full century of professional racing where death was commonplace, organizers realized, as we all did at this year’s Daytona 500, the sport simply could not be sustained if it continued to kill its drivers on live television.

There’s a touch of controversy to the book because it’s based on the idea that the brilliant work of so many dedicated racing professionals to achieve the safety revolution might have faltered absent the HANS Device. That’s the organizing principle of the story and the reason for the other subtitle: “How the HANS Helped Save Racing.” I worked directly with HANS inventor Dr. Robert Hubbard and his business partner, five-time IMSA champion Jim Downing, to write the book. But the thesis is entirely mine. Resolving the issue of basal skull fractures was the one thing sanctioning bodies could not figure out entirely on their own. During the 1990s, this type of injury was the most frequent cause of death or critical injury in all forms of major league racing around the world.

There’s no doubt all the elements of safety developed by NASCAR came into play on this year’s Monday running of the Daytona 500. The cockpit safety cocoon with its carbon-fiber seat, six-point harness, the head surrounds and a head restraint were the first line of defense. The SAFER barrier did its job—which includes sufficiently reducing g-forces so that the cockpit restraints could do their job without being compromised. The impacts of Newman’s Ford getting hit in the door and then the final impact of landing on its roof – in addition to the initial impact with the wall – all showed the value of NASCAR’s Gen 6 car construction requirements.

When it comes to safety, NASCAR operates from its own dedicated Research and Development Center in Concord, N.C., which makes it the world leader. (The FIA’s Formula 1 and IndyCar must rely, in part, on vendors instead of a fully equipped staff under one roof.) Although it’s not really feasible, I, for one, would like to see the in-car video from Newman’s cockpit taken by one of the recent innovations of a digital camera installed to observe what happens to the driver during a crash.

It’s not as if the safety revolution stands still. F-1 has introduced the life-saving Halo and IndyCar enters the 2020 season with the first generation of the Aeroscreen in place. Roger Penske’s ownership may yet lead to improvements in track fencing for open-wheel cars. Competitors to the HANS have emerged and the cost of a certified head restraint continues to decrease without a compromise in safety. (My favorite new arrival is the innovative Flex made by Schroth.) Weekend warriors can no longer offer the excuse that head restraints, which are needed in all forms of auto racing, are too costly, too uncomfortable or don’t fit in their vehicle.

History reminds us that far too many drivers died while Rome was burning and before the major sanctioning bodies recognized they needed to apply their technical and financial resources to greatly reduce the chance of death behind the wheel. The sanctioning bodies realized they had to act to save a sport dependent on the fan appeal of star drivers and dependent upon participation by car manufacturers, TV networks and corporate sponsors. This Daytona 500 was a reminder they did the right thing.

(Editor’s Note: Jonathan Ingram is entering his 44th year of covering motor racing. His seventh book “CRASH! From Senna to Earnhardt—How the HANS Device Helped Save Racing” is in current release. His Amazon bio is located at https://amzn.to/2wwPQ3V . To see “CRASH” excerpts, visit www.jingrambooks.com.)

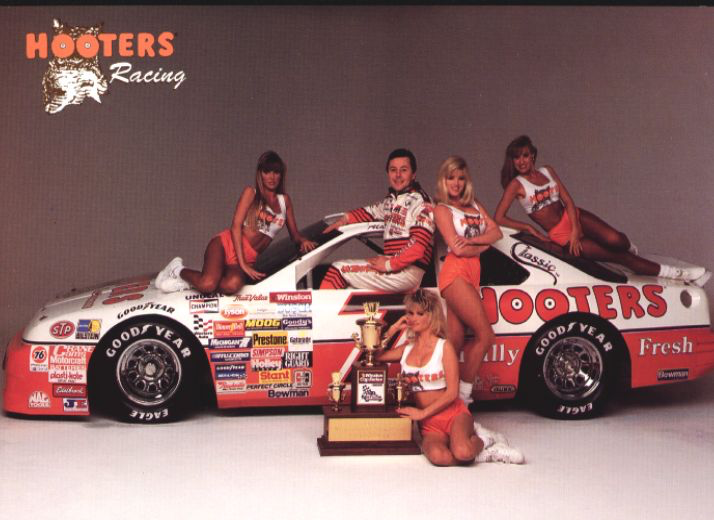

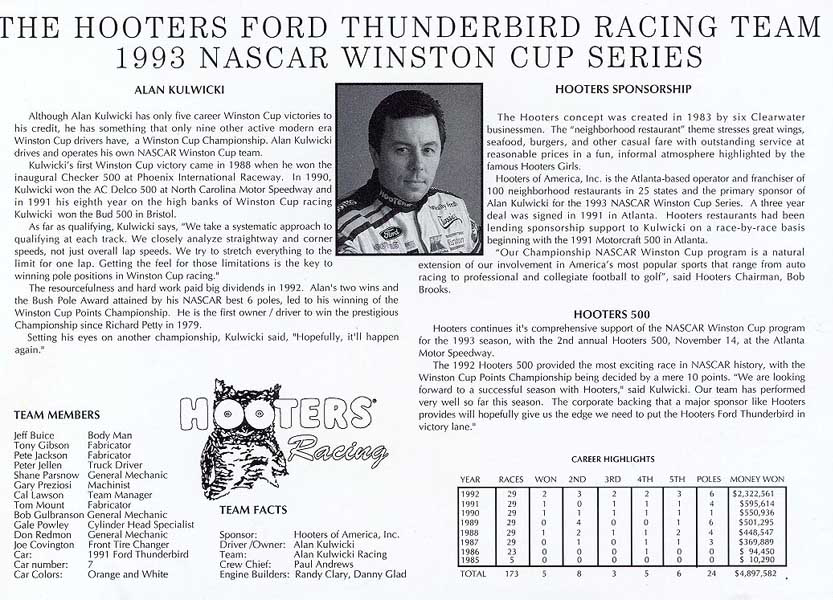

In mid-November 1992, thanks to leading 103 laps in the Hooter’s 500 at the Atlanta Motor Speedway, Alan Kulwicki was able to secure the five bonus points for leading the most laps in the race, which would, in turn, then allowed him to finish second to Bill Elliott and yet still secure the Winston Cup title. Bill Elliott, driving for Junior Johnson, led for 102 laps, the difference of that one lap deciding the championship in the favor of Kulwicki, despite Elliott winning for the fifth time that season.

It was, of course, somewhat more complicated than that. There were, after all, twenty-eight events in NASCAR’s Winston Cup Series prior to the Hooter’s 500 in November. The Bill Elliott versus Alan Kulwicki battle for the title as the race wound down was not necessarily what might have been expected when the green flag dropped to start the race, which was, incidentally, the last for Richard Petty and the first Winston Cup start for Jeff Gordon. Coming into the race, the points leader was Davey Allison, not Elliott. The lead for the championship had changed after the previous event, the Pyroil 500 at the Phoenix International Raceway, two weeks previously.

Alan Kulwicki, during the 1992 season. Photo: Hooter’s

Davey Allison held the lead in the points standings for much of the season before Elliott moved past him at the Miller 500 at the Pocono International Raceway in mid-July. Elliott was about to take a slim nine-point lead in the standings thanks to Allison having a massive crash that left him with a broken right collarbone, forearm, and wrist. That Allison was not injured more severely was little short of a miracle given that his Ford Thunderbird rolled eleven times, slammed into the guardrail and ultimately came to rest on its roof.

At the next race, the Diehard 500 at the Talladega Superspeedway, using Bobby Hillin Jr. as a relief driver to be credited for finishing third, the injured Allison managed to take a one-point lead over Elliott. However, from the Budweiser at the Glen in August until the Phoenix race, Bill Elliott held the lead in the Winston Cup standings. It was not without problems, however. He blew an engine at the Goody’s 500 at Martinsville and suffered with an ill-handling car during the Tyson 400 at North Wilkesboro, relegating him to a 26th place finish. He then hit the guardrail and broke a sway bar during the Mello Yello 500 at the Charlotte Motor Speedway, spending eighteen laps in the pits for repairs. But after the AC-Delco 500 at Rockingham, with a sixth-place or better finish at the remaining two events on the calendar (Phoenix and Atlanta), Elliott was in a position to clinch the Winston Cup championship.

Tribute Card issued by Hooter’s after Alan Kulwicki won the 1992 Winston Cup Championship that was used during autograph sessions. Credit: Hooter’s

At Phoenix, Elliott’s Thunderbird cracked a cylinder head and started overheating, relegating him to a thirty-first place finish. This allowed Allison to retake the points lead with his win. A fourth-place finish by Kulwicki moved him past Elliott and into second place in the standings. As they headed towards the season finale, Allison was now the leader, with Kulwicki thirty points back, and Elliott forty points in arrears. Also within striking distance, mathematically or at least possibly or theoretically, were Harry Gant, Kyle Petty, and Mark Martin. The latter three would require some very serious problems among the top three given that Gant and Petty were over fifty points behind.

What all this meant was that to be the 1992 Winton Cup champion, Davey Allison simply needed to finish fifth or better to ensure the title regardless of whatever the others might end up doing. Plus, he had a thirty point buffer over Kulwicki with an additional ten points on top of that over Elliott. In other words, it seemed quite reasonable that Davey Allison would emerge as the 1992 champion, especially in light of the difficulties facing Kulwicki and Elliott, not to mention Allison coming off a victory at Phoenix, having the momentum that success creates going into the finale.

The Atlanta race was run under a points schedule that was put in place by NASCAR beginning with the 1975 season. It replaced a series of point systems that were often confusing to fans and teams alike. Until the 1968 season, the Grand National series, as it was then known, used a combination of prize money and distance to determine the points awarded for an event. In 1964, for example, points were awarded using sixteen different schedules based upon the prize money posted and the distance of an event. From 1968 60 1971, this somewhat chaotic system was replaced by a very simple three-tiered system: points were awarded for events less than 250 miles, those between 251 and 399 miles, and those 400 miles or longer.

In 1972 and 1973, points were awarded based upon the finishing position and then with additional points given according to the number of laps completed in a race. If that system wasn’t enough of a bookkeeping nightmare, in 1974 NASCAR managed to outdo itself: Winnings from purse posted for an event, with qualifying and contingency awards not counting, multiplied by the number of races started, with the resulting figure divided by 1,000 determined the number of points earned in the championship. Needless to say, it turned out to be so hopelessly difficult to compute that even the teams were more often than not often confused trying to figure it out. Although the 1974 system has been the subject of a massive case of organizational amnesia in Daytona Beach, the system was clearly intended to reintroduce one of the major components of how NASCAR – and Big Bill France in particular – weighed the early points system by giving emphasis to the prize money being awarded.

In 1975, Bob Latford – usually referred to as a NASCAR “historian,” but in reality, a public relations flack for the organization who also just happened to be a high school classmate of Bill France, Jr. – devised a system that was used from 1975 through the 2003 seasons. It awarded points on a sliding scale in increments of five, four, three, two, and one down to fifty-fourth place, beginning with 175 points for first place. Points were awarded for an event regardless of the distance or the purse that was posted. Five bonus points for leading a lap with an additional five points for the driver leading the most laps in a race.

This meant that a driver finishing second in a race, earning 170 points, could earn five more points for leading a lap, and another five points for leading the most laps. In other words, with the winner getting an automatic additional five points thanks to leading a lap, earning 180 points, it also meant that a driver finishing second, 170 points, could equal the points awarded to the winner by leading the most laps in a race, therefore adding ten bonus points to his score, also earning 180 points.

It was this quirk in the points system that came into play as events played out during the Hooters 500 at Atlanta in 1992. As mentioned, although it was theoretically possible for Harry Gant, Kyle Petty or Mark Martin to win the championship, this meant that Davey Allison, Alan Kulwicki, and Bill Elliott all needed to fall out of the race very early on, earning very few points, and that one of the trio needed to win the race. As it turned out, Martin retired with engine trouble and neither Gant or Petty were much of a factor at the end, finishing thirteenth and sixteenth, respectfully.

Needing only to finish fifth or better to wrap up the championship regardless of what Kulwicki or Elliott did, Davey Allison’s championship hopes ended less than fifty laps from the end. Running in the top five most of the time, making sure to gain five bonus points by leading a lap thanks to pitting late during the third caution period, Allison’s Thunderbird was shoved into the wall by the Chevrolet of Ernie Irvan when the Morgan-McClure team driver lost control in the fourth turn. With the damage to the car such that Allison was out of the race, the attention now shifted to the cat-and-mouse game that the Junior Johnson and Kulwicki teams had been playing just in case something like this happened.

The decision by Kulwicki’s crew chief, Paul Andrews, to stay out an extra lap while leading, ensuring that the five bonus points for leading the most laps was critical for Kulwicki. This meant that by finishing second, even if Elliott won the race and collected 180 points, that Kulwicki’s second-place points total of 170 would have an additional ten points added, therefore equaling Elliott’s 180 points. Had Elliott and Kulwicki finished first and second, but with Elliott collecting the five bonus points for leading the most laps, his 185 points and Kulwicki’s 175 points would have resulted in a tie: 4,073 points each. With the tiebreaker being the total number of wins in the season, Elliott would have become the 1992 Winston Cup champion, with his five wins against Kulwicki’s two wins.

Alan Kulwicki’s Ford Thunderbird, with Ford’s permission, ran the race as an “Underbird,” with a cartoon Mighty Mouse on board also adding emphasis to the team’s position as the underdog in the championship fight. That Alan Kulwicki Racing defeated the Junior Johnson team, which had attempted to hire him at one point, also meant that by earning the 1992 title Kulwicki also ended up as the last owner-driver to do so. Alas, on 1 April 1993, Kulwicki and three others died when an aircraft owned by the Hooters restaurant chain crashed on its way to the Bristol International Raceway. Later that year, on July 12, 1993, Davey Allison crashed his Hughes 369 HS helicopter while landing at the Talladega Superspeedway, dying the following day.

Alan Kulwicki hoisting the Winston Cup Championship Trophy, at the conclusion of the Hooter’s 500, Atlanta on November 12, 1992. Photo: Racing One/Getty Images.

If the legacy of the 1992 fight for the Winston Cup ultimately ended in tragedy for Alan Kulwicki and Davey Allison, there were other notable aspects to the season as well. One of them was the debut of Joe Gibbs Racing, a single-car team with Dale Jarrett driving a Chevrolet Lumina sponsored by Interstate Batteries. The addition of a lighting system for The Winston, the series all-star event held at the Charlotte Motor Speedway was not only a spectacular success at the time, but a harbinger of the future that the Daytona added later for racing under darkness.

There was also the deaths of Anne and Bill France, Sr. in January and June, respectively. Although Big Bill had turned over the helm of NASCAR to his son, Bill Jr. in 1992, Big Bill’s presence still loomed over the organization. His death was literally the end of an era for NASCAR, the links to its origins beginning to fade and its mythology becoming even more embedded in American folklore and the culture of motorsport. That said, it was Anne France who was possibly the real reason that NASCAR both survived and literally prospered: it was Mrs. France who ran the financial side of the family business, who kept the books and an eye on the real moneymaker for NASCAR, the Competition Liaison Bureau, the entity to which the promoters posted their purses so as to guarantee that the money would be available at payout time.

That, of course, is another story…

WATKINS GLEN, N.Y. (Aug. 7, 2015) – In an evening filled with tributes and taunts, Richard Petty was honored on Thursday, Aug. 6, with the Cameron R. Argetsinger Award for his contributions to racing.

The dinner was held at the famed Corning (N.Y.) Museum of Glass in advance of the Cheez- It 355 at The Glen NASCAR race this weekend at Watkins Glen International in upstate New York. The dinner was presented by NASCAR, International Speedway Corp. and WGI.

Extras: IMRRC Honors Richard Petty with Cameron R Argetsinger Award for Outstanding Contrib

The International Motor Racing Research Center honored “The King,” the winningest driver in racing and a noted philanthropist, with the award in front of a capacity crowd of race-car drivers, sponsors and industry and local dignitaries.

Introduced as “the world’s best ambassador for NASCAR,” Petty said he has committed himself through his entire career to acknowledging and appreciating the people who have made his achievements possible, listing fans, team members, sponsors and the people who buy sponsors’ products.

“I feel like I’ve been really lucky,” he said. “How many millions of people did it take to get me up here? You can’t say thank you enough.”

The award dinner was a fund-raiser for the IMRRC, an archival and research library dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of motorsports.

“It’s an amazing facility, filled with one-of-a-kind things,” Master of Ceremonies Dr. Jerry Punch told the crowd. “You owe it to yourself to visit. You’ll be absolutely amazed at what it holds.”

In tribute to Petty, Punch interviewed current Richard Petty Motorsports drivers Aric Almirola and Sam Hornish Jr., as well as Petty’s legendary crew chief Dale Inman, in a chatty session among the three.

Almirola recalled a lesson in how to pass, given on a napkin with a Sharpie.

Petty, he said, doesn’t buy into all the talk of aerodynamics and “dirty air.”

“So I listen, and I’ve tried really, really hard not to let the car in front of me hold me up. And, he’s always right,” Almirola said, adding, “You have to listen to ‘The King.’ He pays the bills.”

Hornish said he was grateful for guidance and encouragement from Petty, calling him a positive role model.

Petty’s long-time crew chief Inman said Petty was simply great with a car throughout his career, but he wanted the audience to know that Petty’s greatness continues with his generous community work.

Ten years ago, the Pettys established Victory Junction, a summer camp for children with medical conditions or serious illnesses. In his remarks, Petty told the dinner audience that 22,000 children have attended the camp since its beginnings.

“The good Lord put us here for a reason. We just went through the racing part to get to the part He wanted us to do,” Petty said.

Multi-team owner Chip Ganassi, last year’s inaugural recipient of the Cameron R. Argetsinger Award for Outstanding Contributions to Motorsports, congratulated Petty on being this year’s honoree, saying, “Hell, he is everyone’s racing hero. He and his Petty-blue 43 are both sports icons. They go together every bit as much as Mickey Mantle and pinstripes or Mean Joe Green and the steel logo on his helmet.”

Appropriately, IMRRC President J.C. Argetsinger explained that one of the Center’s missions was to be the “Cooperstown, N.Y., of motor racing.” “We are absolutely thrilled to be honoring Richard Petty. The Pettys are the first-family of American racing,” Argetsinger said, citing Lee Petty’s race at Watkins Glen in 1957, followed by father and son, Lee and Richard, both racing at The Glen in 1964. In 1992, it was again father and son at The Glen: Richard and Kyle.

“It’s part of the sport’s history, and we’re proud of our role of preserving that history,” Argetsinger said.

The award memorializes Cameron R. Argetsinger, founder and organizer of the first races at Watkins Glen.

Petty’s son, longtime race-car driver and T.V. racing analyst Kyle, as expected threw some barbs at his famous dad.

“I don’t know why you’re honoring him here. He’s never won at Watkins Glen,” said Kyle, who won that 1992 race.

Kyle, too, cited his father’s philanthropic work and the positive impact he has had communities and individuals. “He’s a bigger champion away from the race track than he ever was on the race track,” Kyle said. “You’re not only getting the greatest driver that ever sat in a race car, you’re getting the greatest human being that I have known in my life.”

Video shout-outs from NASCAR drivers Tony Stewart, Jeff Gordon and Jimmie Johnson were shown, as well as a fitting tribute video to “The King” produced by NASCAR Productions especially for the evening. WGI President Michael Printup presented a video of amusing television coverage out-takes from Petty’s career, eliciting laughter and applause. Other speakers included Indy 500 champion Bobby Rahal, chairman of the IMRRC Governing Council, and Smithfield Foods Vice President, Corporate Marketing, Bob Weber.

“Richard Petty is the single highest recognizable motorsports driver of all time and the most trusted driver,” Weber said, representing one of Richard Petty Motorsports major sponsors. “It’s a great connection for us.”

The evening concluded with a spirited bidding war for an original painting by motorsports artist Randy Owens, depicting Petty’s 200th win at Daytona International Speedway on July 4, 1984. It went for $4,500.

Also auctioned off was a surprise gift donated by Petty: one of his iconic hats preserved in a display case. Punch and Petty skillfully manipulated the bidding to also include the hat Petty was wearing, fetching $9,000 for the pair between two bidders.

A silent auction of Petty memorabilia and other high-quality donated items was also held.

The evening’s proceeds benefits the IMRRC, an archival and research library dedicated to the preservation and sharing of the history of motorsports, of all series and all venues, through its collections of books, periodicals, films, photographs, fine art and other materials. The IMRRC is a 501(c)(3) charitable organization. For more information about the Center’s work and its programs, visit www.racingarchives.org or call 607-535-9044. The Center also is on Facebook at International Motor Racing Research Center.