More details as we head into 2025; stay tuned. For now, visit NASCAR.com

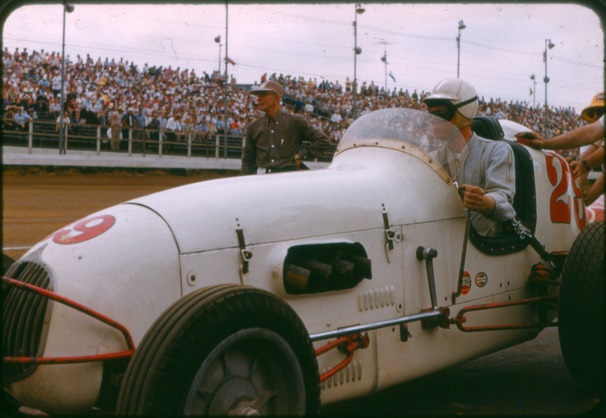

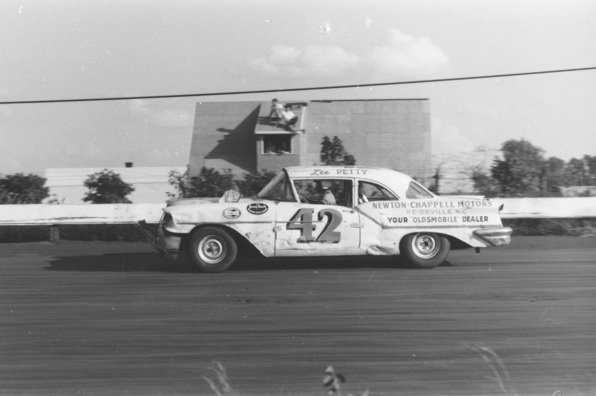

During the last several months, the IMRRC has undertaken processing of the valuable and unique Joseph Braig Photographic Collection, which was donated to us for archival storage without limitations on usage by the Braig family. We prepared a presentation of the material for viewing by Mr. Braig’s widow and extended family when they made a formal visit to the IMRRC in April. This collection is expected to be a major asset to the IMRRC’s photographic resources and will be used in exhibits, presentations, and made available for reproduction, with attribution, under the terms of our fee structure.

Joe Braig was a skilled photographer who was employed by National Speed Sport News, a publication that served as a virtual bible for American motorsports. His rare pictorial documentation of a unique period in motorsport history is the only collection of this scope and quantity known to exist. Joe Blinebury, Jr., noted motorsports historian, characterized this collection as a “collector’s treasure” and of “museum quality.” Chris Economaki, editor and publisher of National Speed Sport News, a major figure in American motorsports who became a close friend of Mr. Braig, said, “Joe’s photos are among the very best we ever published.”

In addition to fascinating scrapbooks maintained by Mr. Braig, the collection consists primarily of many hundreds of individual prints and digital images, the latter often accompanied by contact sheets, of primarily dirt and asphalt oval track motor racing subjects from Langhorne, Williams Grove, Reading Fairgrounds, Trenton, Indianapolis, and other classic oval tracks from the 1950s to the 1980s.

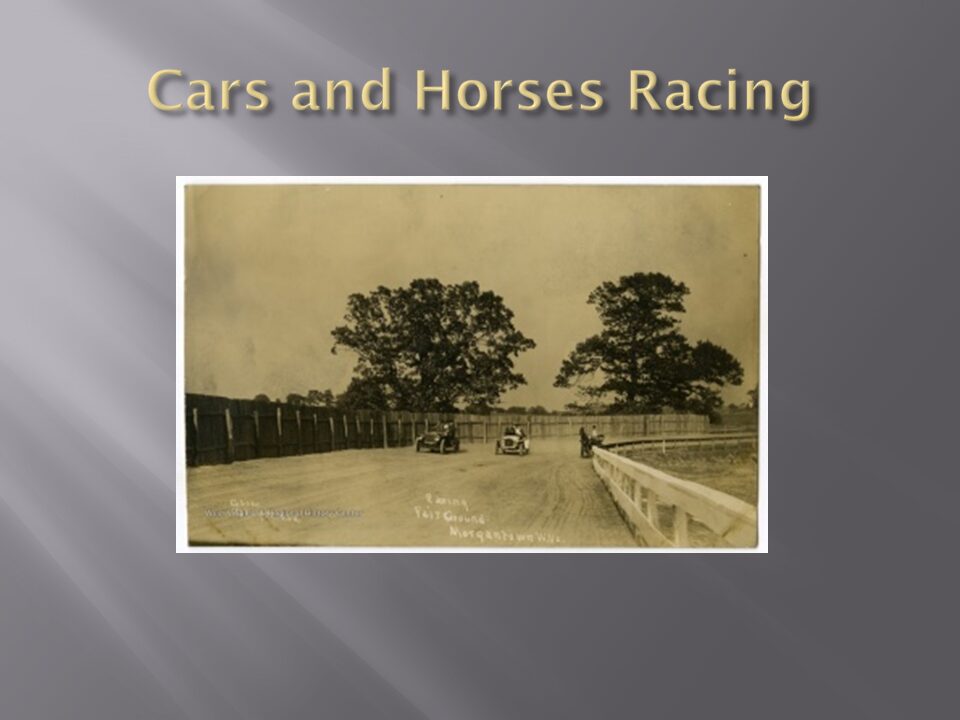

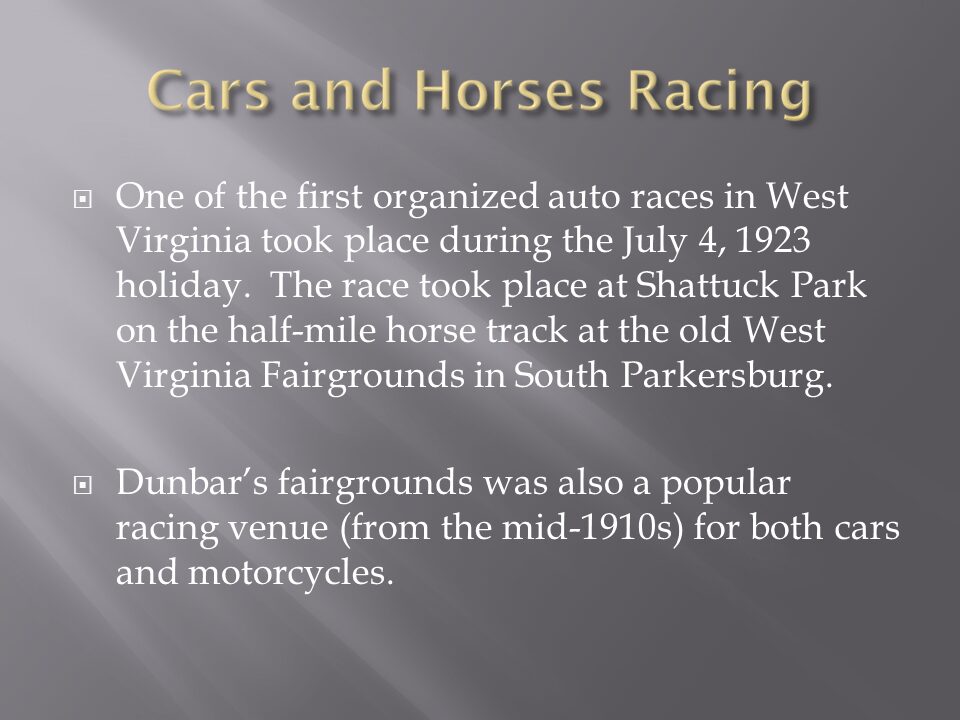

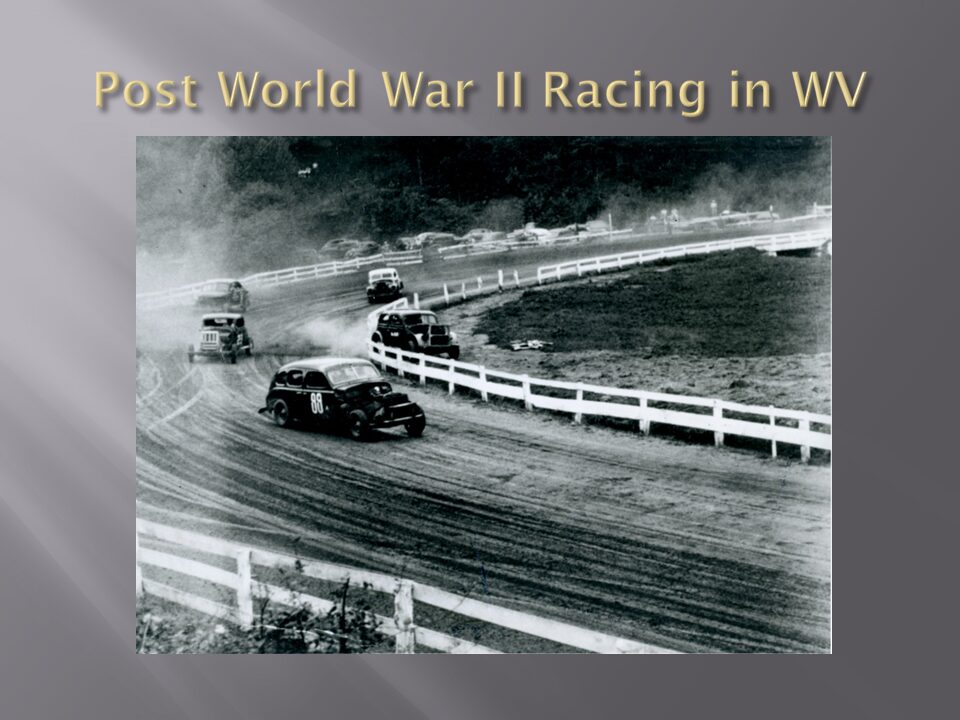

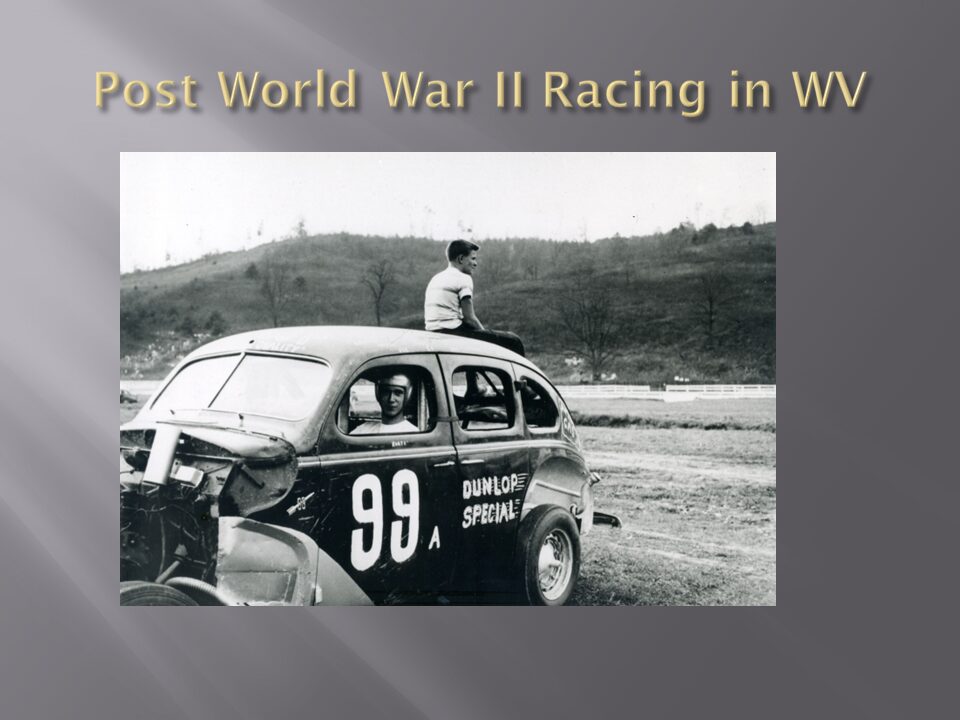

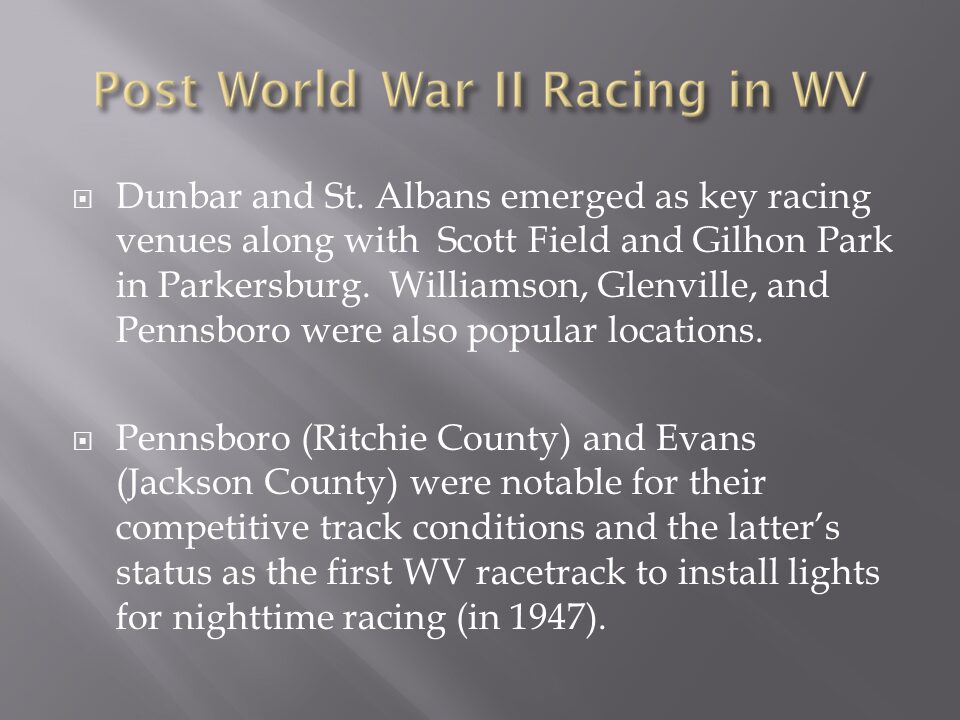

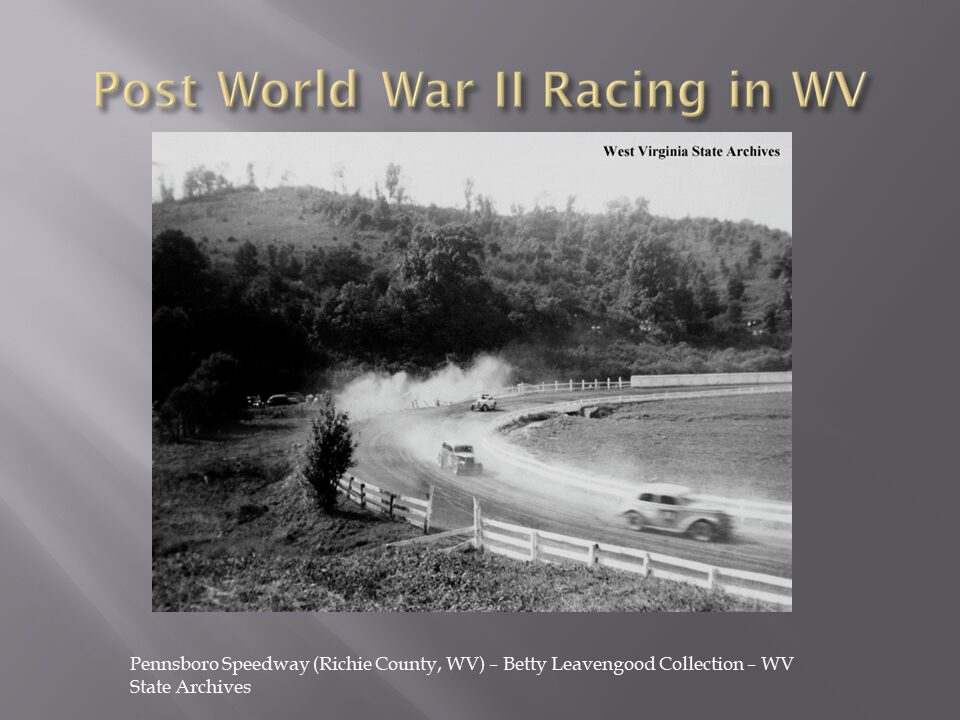

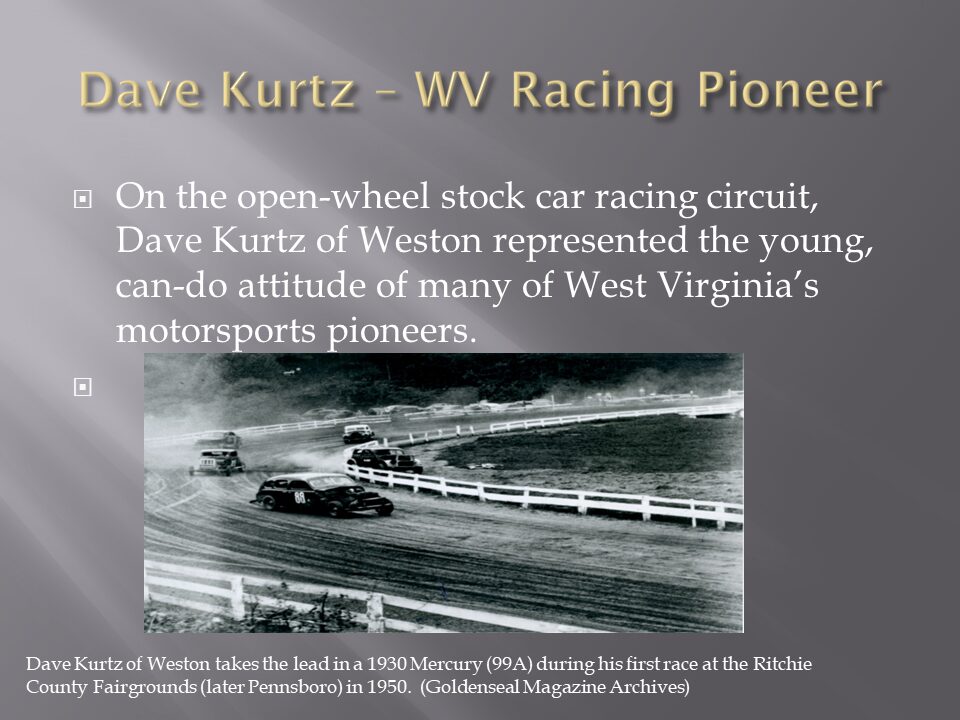

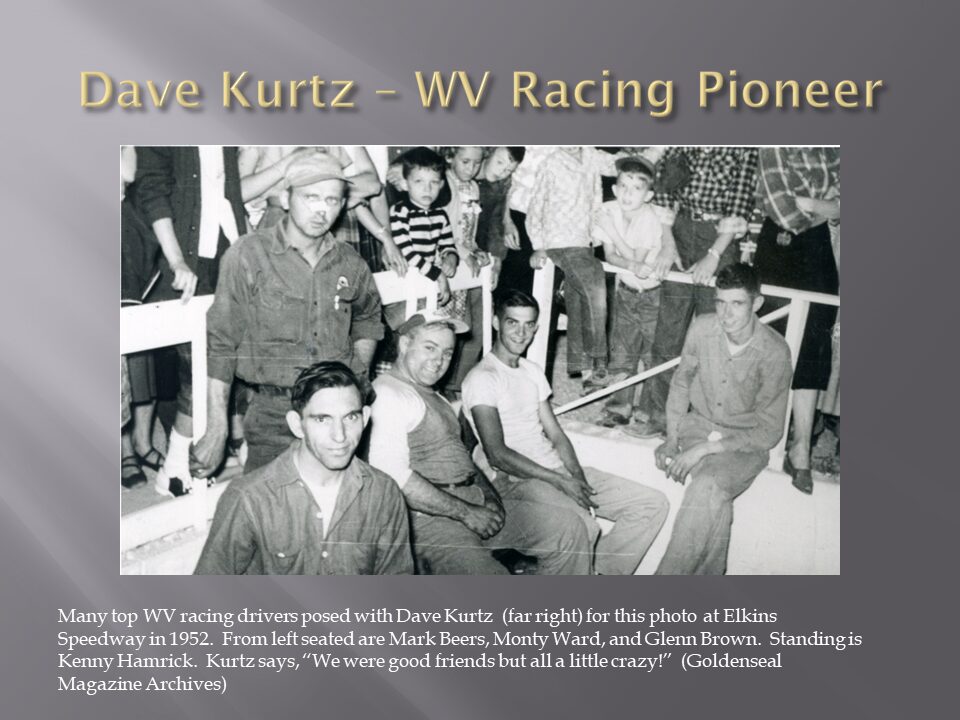

Grassroots and bootstraps strategies were used by early racing pioneers in West Virginia beginning in the 1930s. Tom Adamich, co-author of the auto racing entry in the West Virginia Encyclopedia and other related articles/publications will profile several events and individuals who innovated and dominated on the dirt tracks, ball diamonds, and other unique race courses that dot the hills and valleys of the great state of West Virginia.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Tom Adamich has been a vehicle/motorsports historian since the early 1990s. He served as the project archivist at the Wills Sainte Claire Auto Museum (Marysville, Michigan) from 2009-2016. He has been a frequent presenter at the Argetsinger Symposium – including presentations on Strategic Air Command (SAC) racing history, Cuban motorsports history, and Formula Vee.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

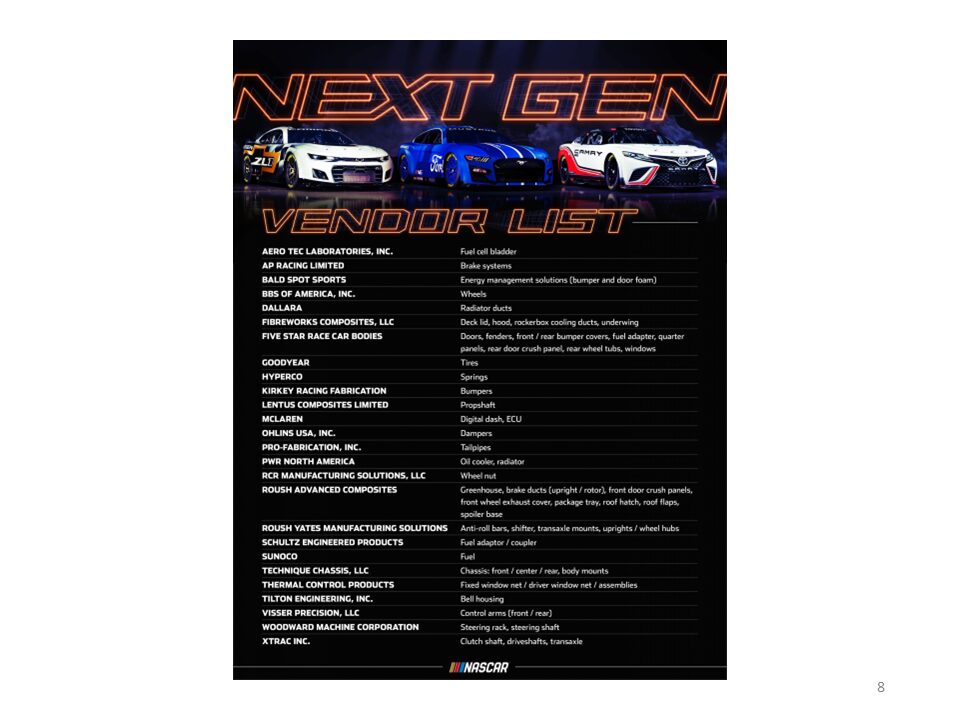

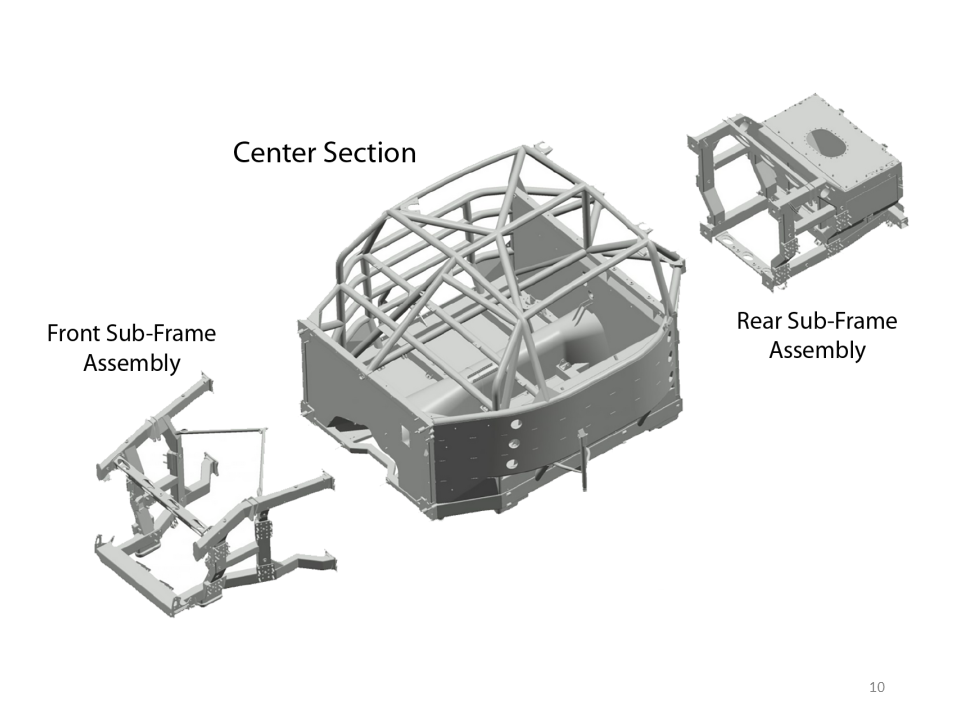

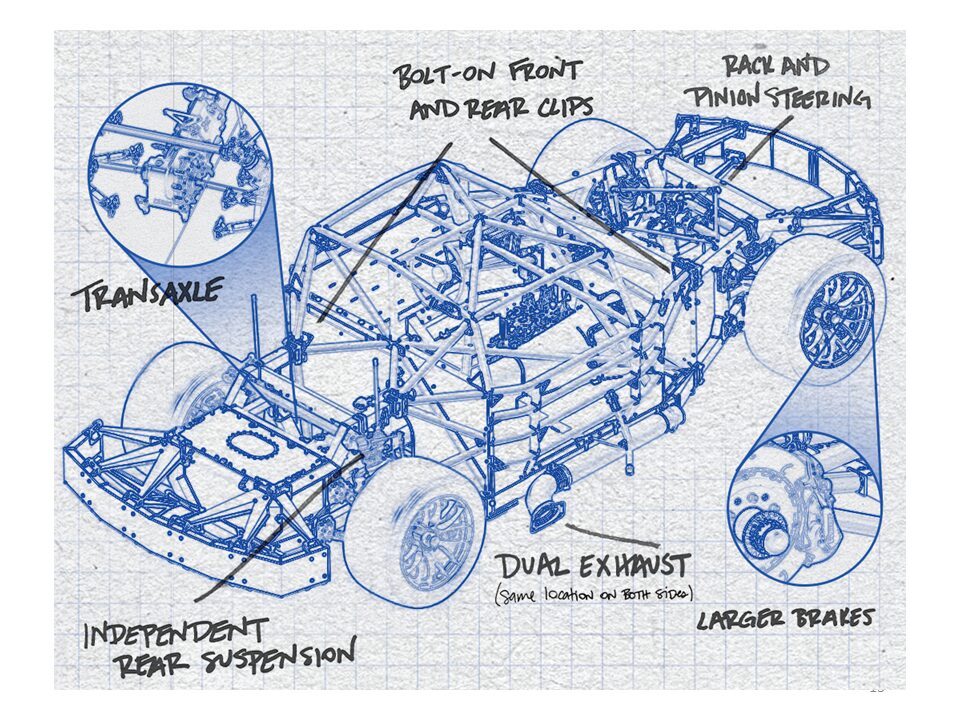

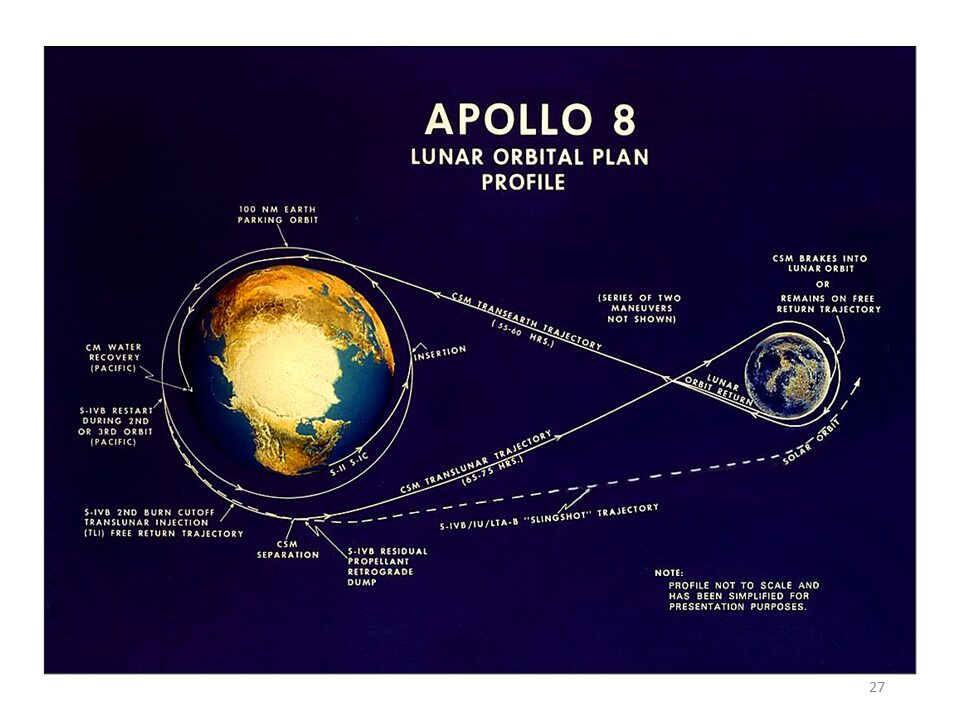

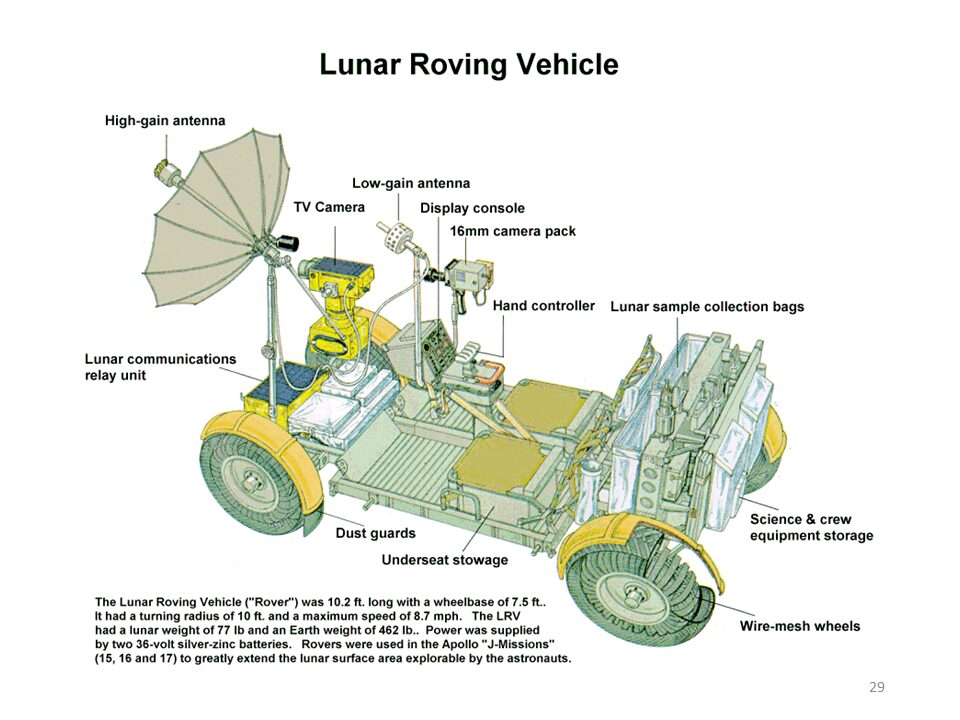

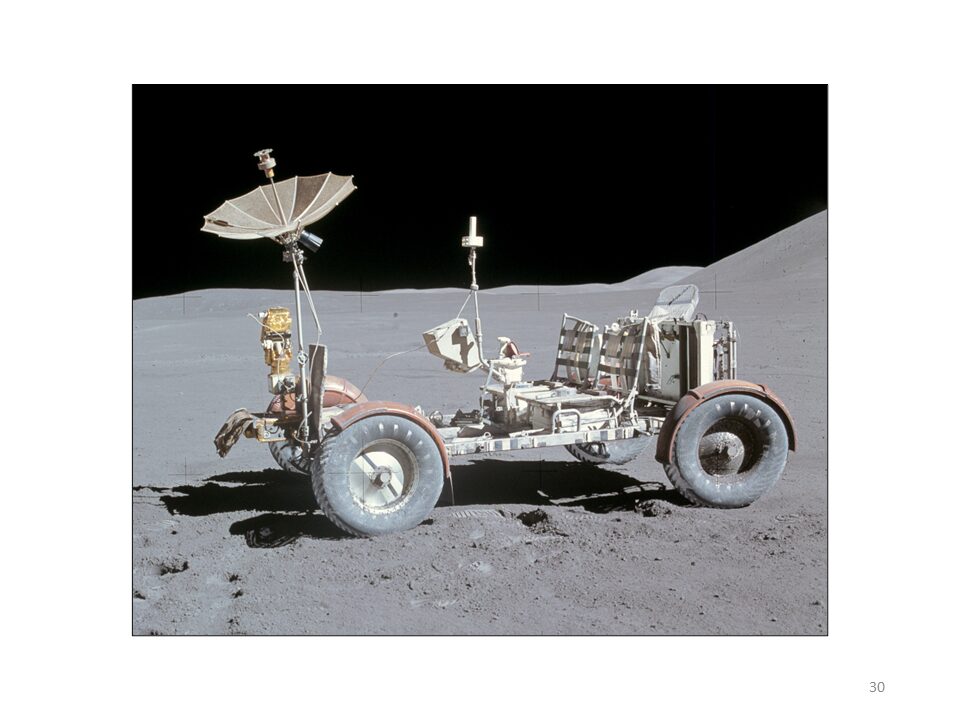

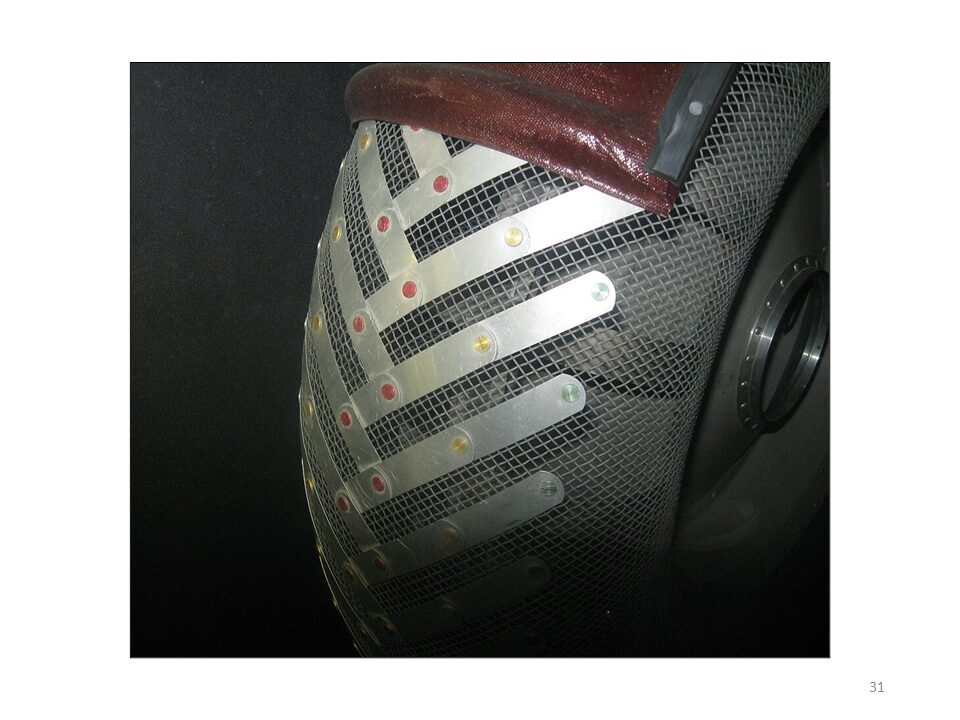

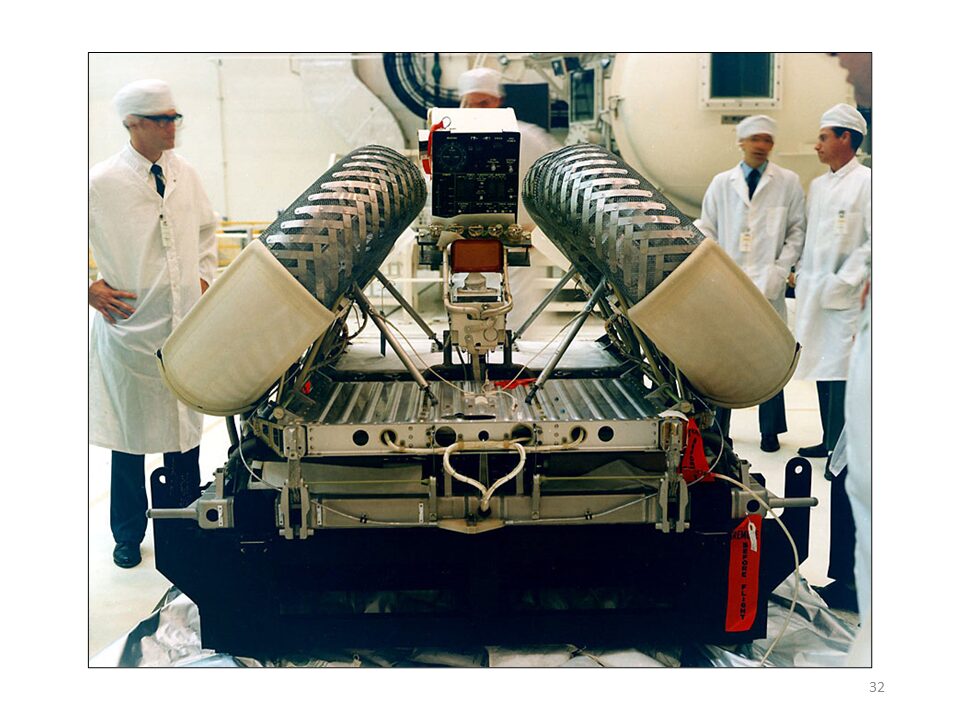

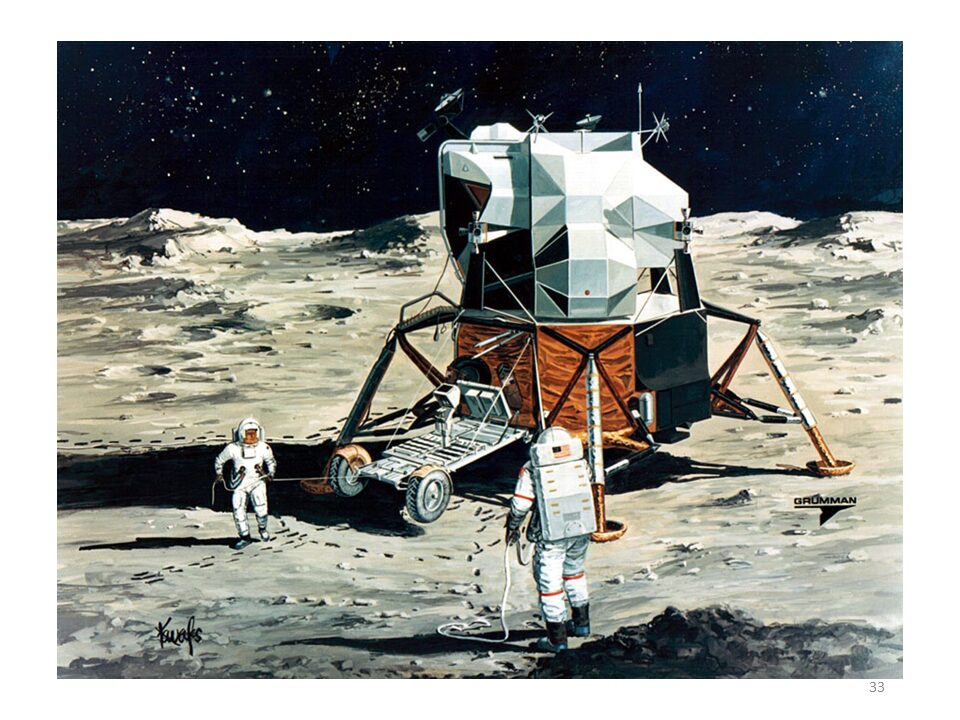

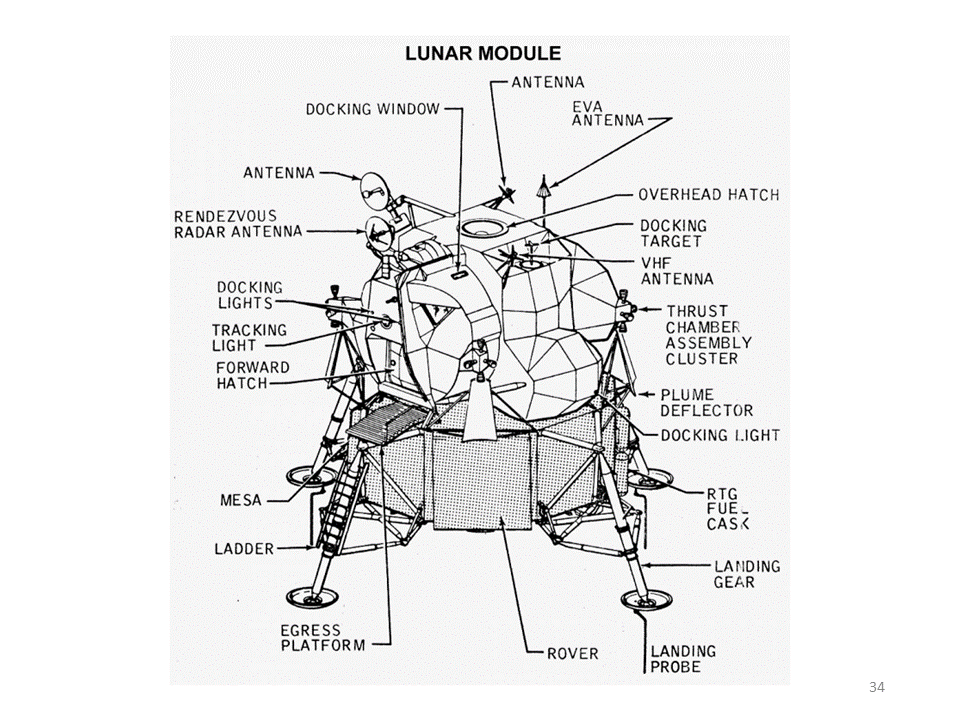

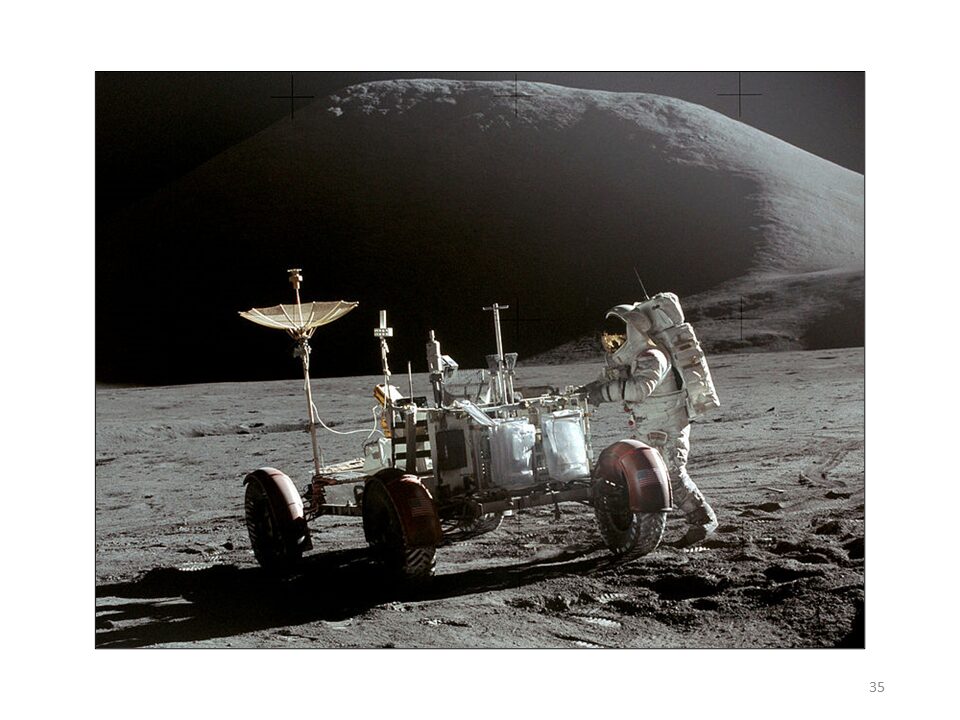

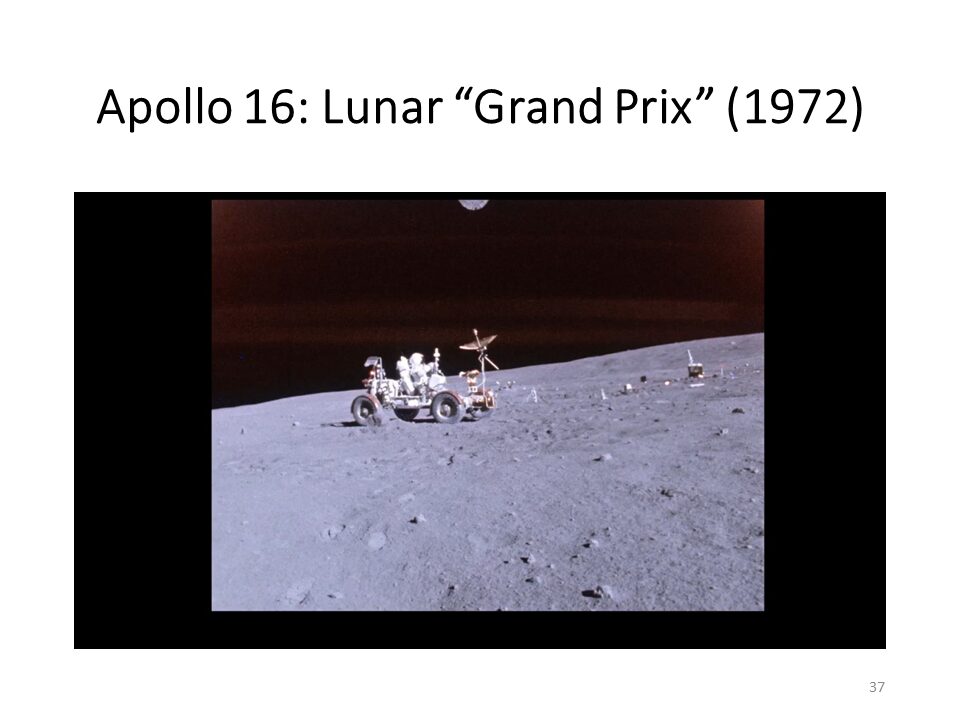

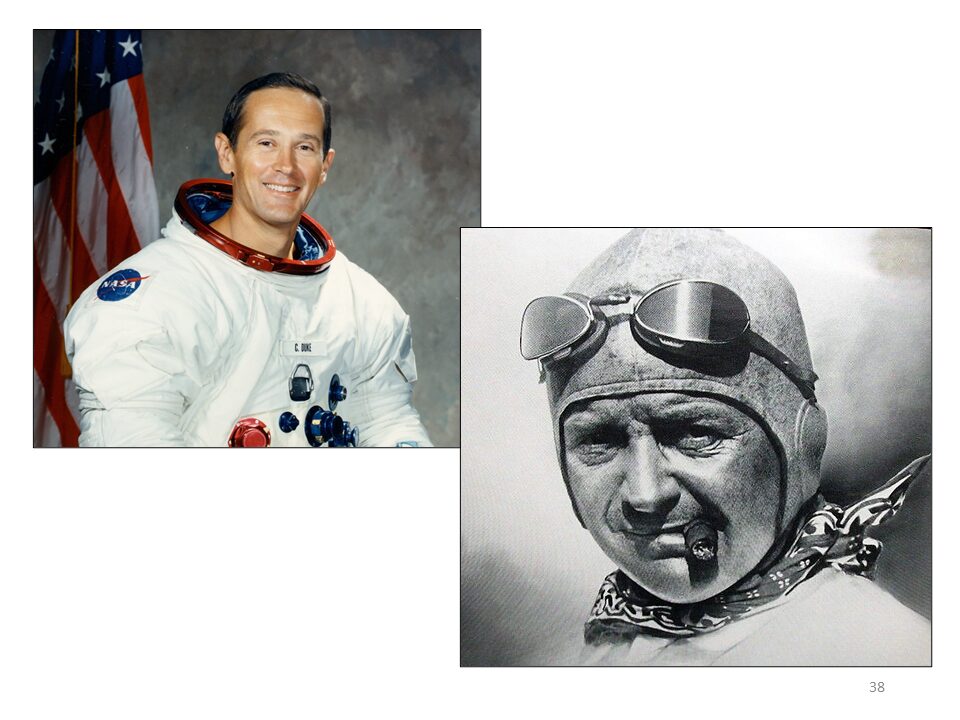

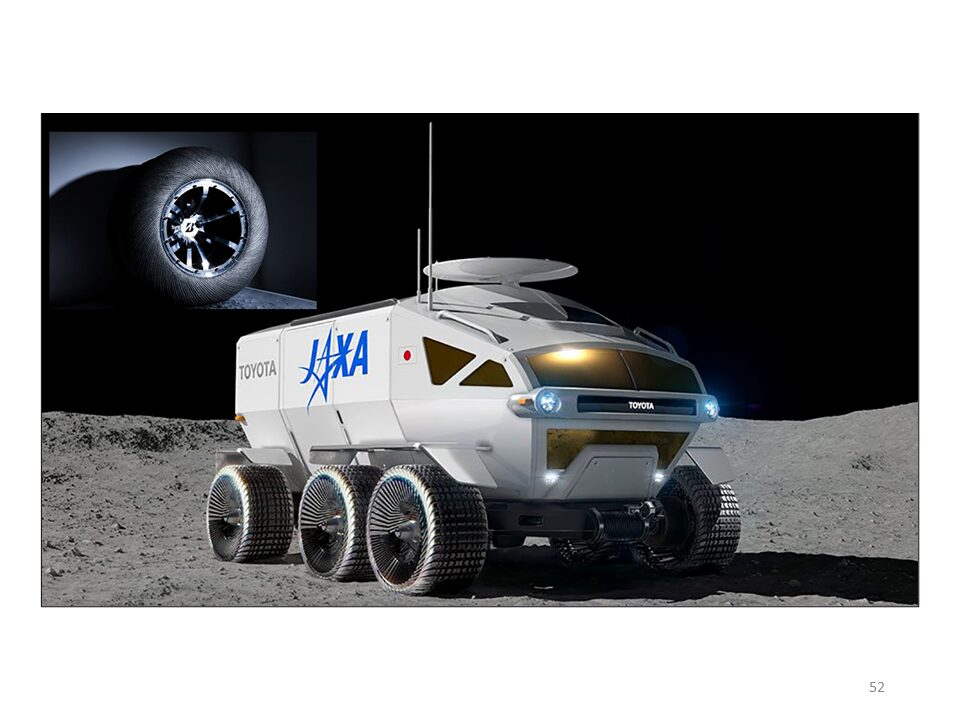

This presentation examines the 2023 alliance between Leidos, the international high-tech engineering firm, and NASCAR to build a “Next Gen” Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV). The paper looks at the adaptation of motorsports culture by the aerospace industry as space exploration grows more privatized and commercialized.

Additionally, the presentation looks at the history of NASA’s LRV program and how astronauts saw their rovers through the context of automobile racing. Both Leidos Dynetics and NASCAR are relying on particular language, imagery, and historic legacies to justify their partnership while trying to earn NASA’s new LRV contract by the end of November 2023.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Dr. Mark D. Howell has been involved with motosports his entire life. As a teenager, he tagged along with the NASCAR Modified pit crew of Brett Bodine, who raced out of Howell’s hometown of Dallas, PA. He earned a BA and MA from Penn State, and a Ph.D. in American Culture Studies from Bowling Green State University. His dissertation evolved into From Moonshine to Madison Avenue: A Cultural History of the NASCAR Winston Cup Series, published by The Popular Press/University of Wisconsin Press in 1997.

Howell is professor of communications at Northwestern Michigan College in Traverse City. He lives with his wife and son (and two dogs) in the village of Suttons Bay on Lake Michigan.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

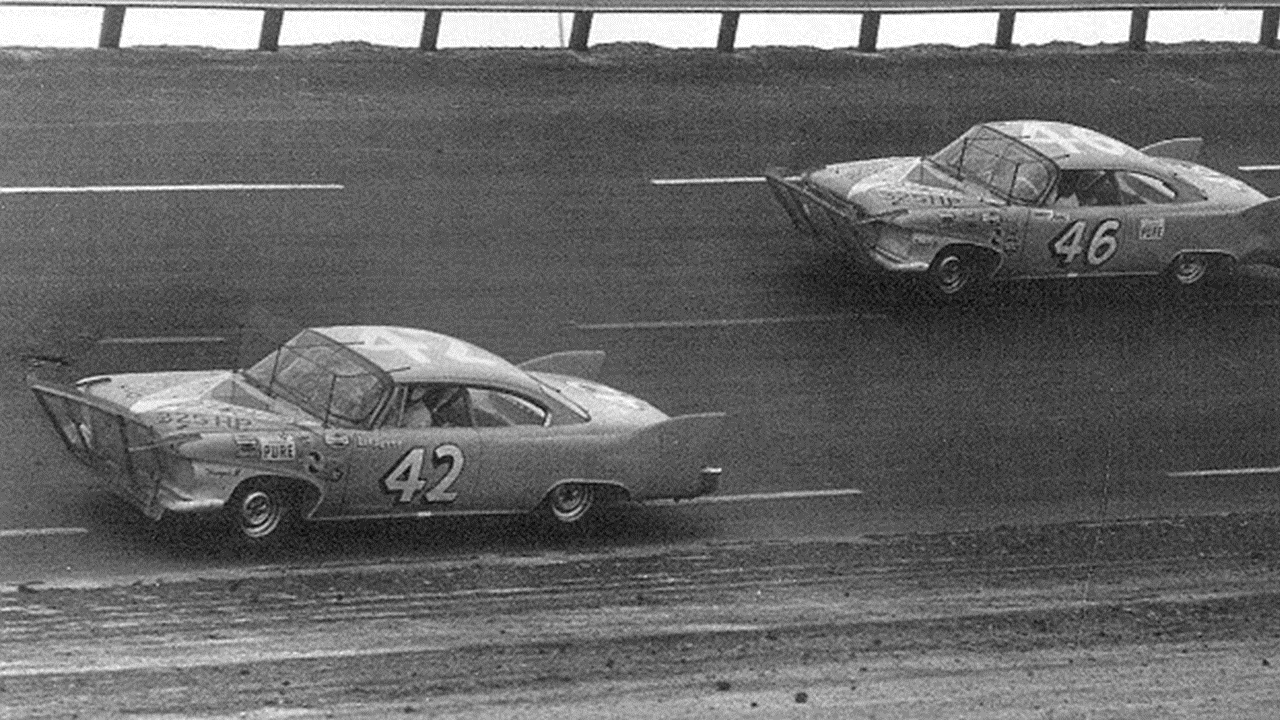

Mackenzie Kirkey’s presentation focuses on NASCAR driver Curtis Turner, the efforts of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters to unionize NASCAR drivers in 1961, and the tactics used by NASCAR’s Founder and President Bill France Sr. to try and thwart their attempts.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Mackenzie Kirkey received his MA in History from Brock University and his undergraduate degree in history from Bishops University.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

Buz McKim’s presentation explores the racing career of NASCAR’s iconic founder William “Bill” France and the origins of NASCAR in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Big Bill’s exploits are legendary and his captivating and sometimes overwhelming style belie his extraordinary contribution to the evolution of professional motor racing in America. McKim’s presentation is a deeply informed and sympathetic portrayal of the man and his accomplishments.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Buz McKim, formerly historian at the NASCAR Hall of Fame in Charlotte, NC, is a distinguished figure in the motor sports world and a much sought-after speaker at motorsports gatherings. Mr. McKim served as director of archives for International Speedway Corporation and as coordinator of statistical services for NASCAR. He is the author of The NASCAR Vault: An Official History Featuring Rare Collectibles from Motorsports Images and Archives.

McKim’s Legends of Racing Radio Show is a hugely popular forum for enthusiasts of the sport. Buz McKim was our Keynote Speaker for two prior Argetsinger symposia.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

THERE ARE NO SLIDES WITH THIS PRESENTATION.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

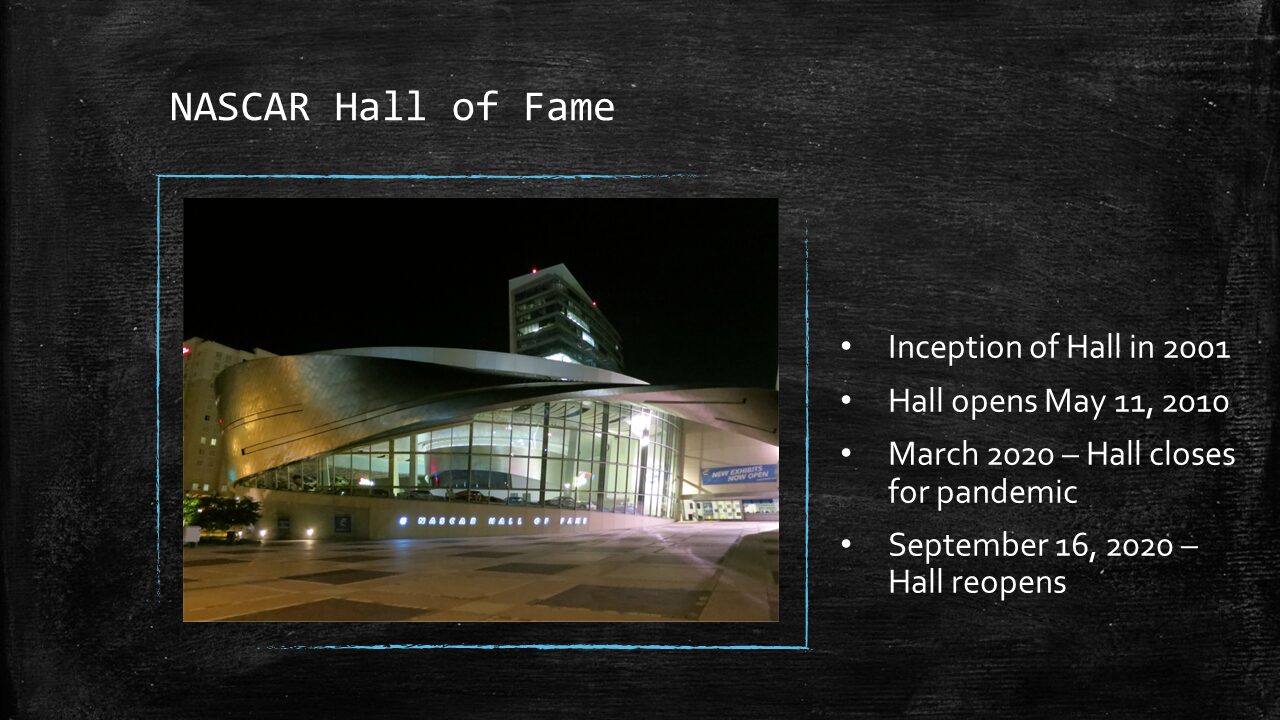

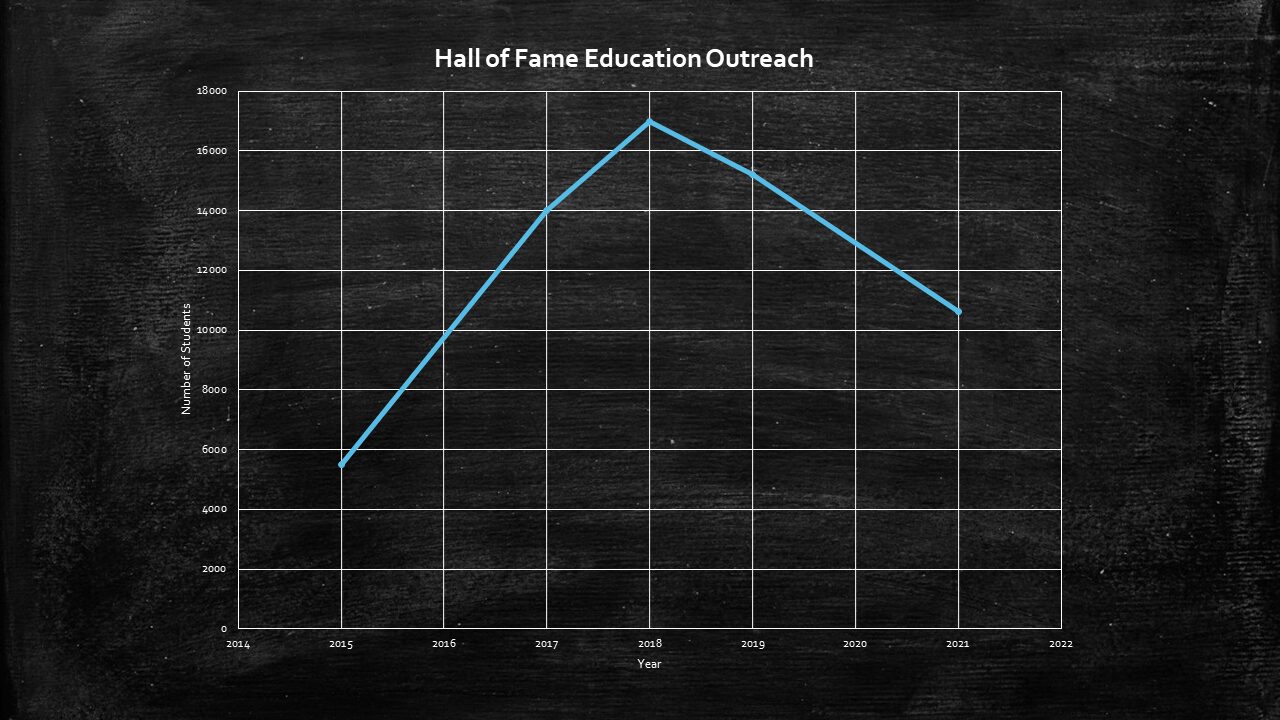

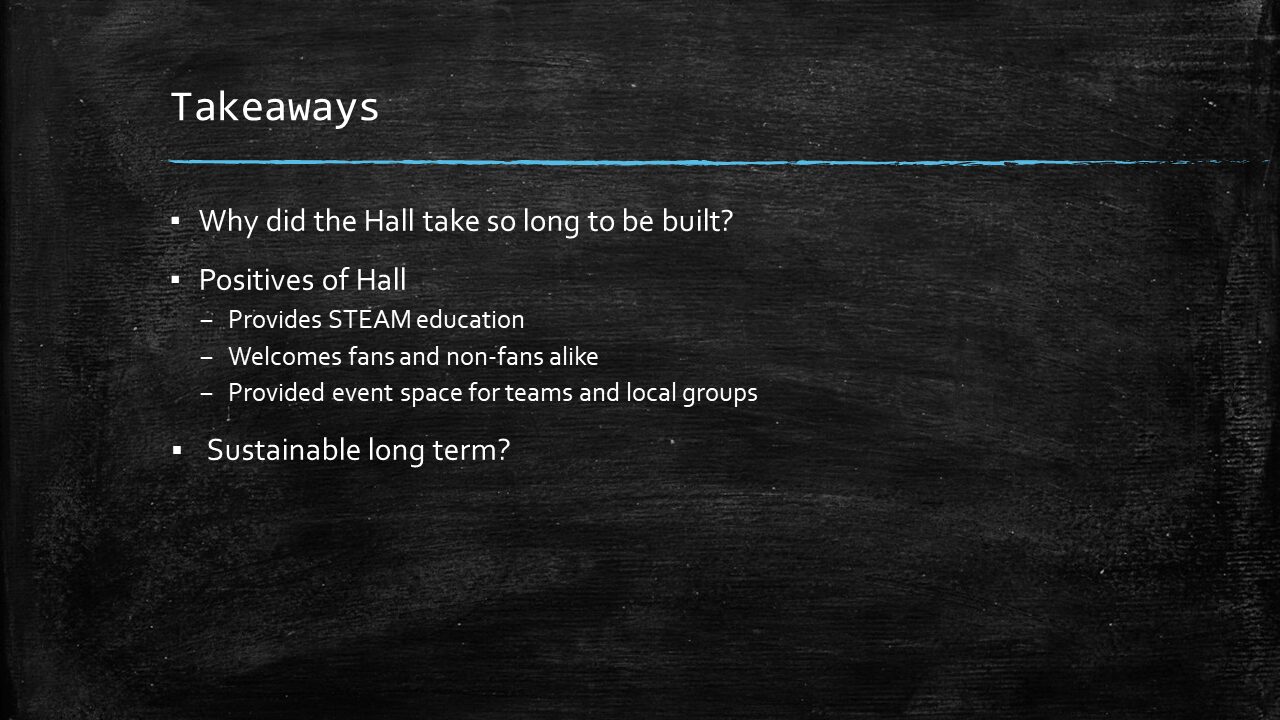

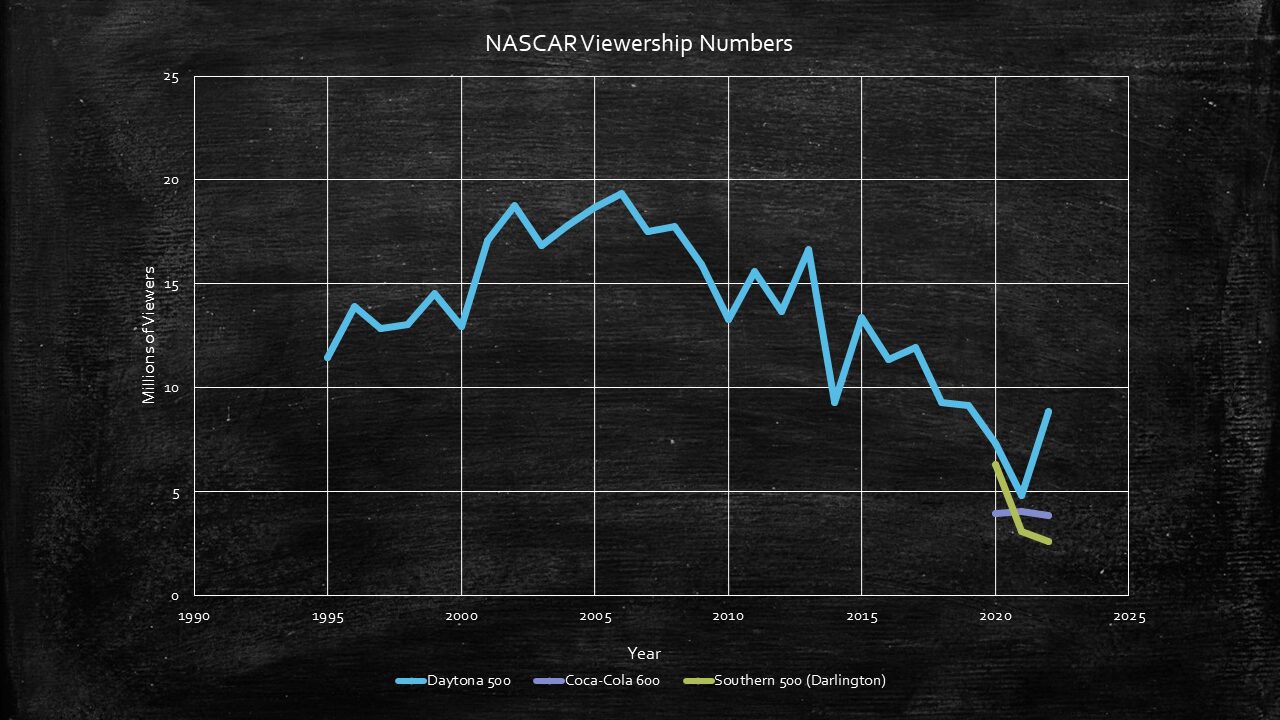

Hannah Thompson examines the history of the NASCAR Hall of Fame from its inception in 2001 through the global pandemic, bringing into consideration why Charlotte was selected as the seat for the Hall and how the Hall has affected NASCAR and its fans. Charlotte is often overlooked in motorsports history despite its lasting impact on the auto racing world.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Hannah Thompson is a cultural historian of the Carolina Piedmont and is new in the museum field with her current position with the Gaston County Museum of Art & History. Ms. Thompson also helps restore Coca-Cola “ghost signs” throughout the Southeast in her spare time.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

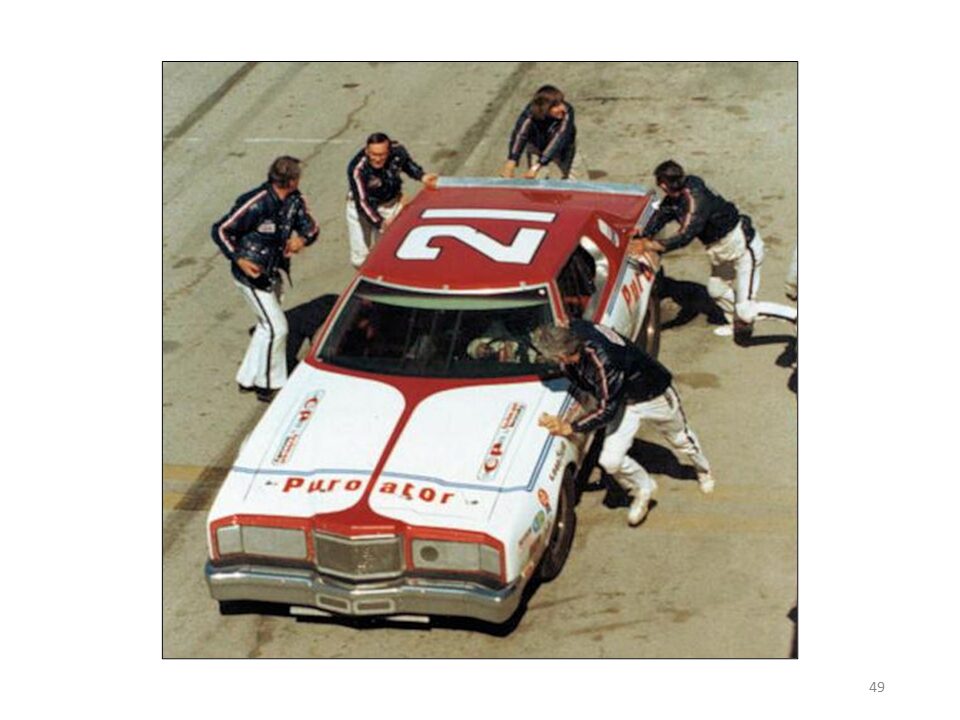

Buz McKim’s presentation explores the origins of modified stock car racing in the illegal distribution of untaxed adult beverages, or “moonshine.” He recounts the development of NASCAR in 1949 and its evolution in the 1950s from a truly “stock” competition to a manufacturer-supported testing ground for advances in the engineering and design of American automobiles. Mr. McKim’s talk describes the irony of how the automotive engineering modifications inspired by “wild country boys” led to all-around improvements in automotive technology.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Buz McKim, formerly historian at the NASCAR Hall of Fame in Charlotte, N.C., is a distinguished figure in the motorsports world and a much sought-after speaker at motorsports gatherings. Mr. Kim served as director of archives for International Speedway Corporation and as coordinator of statistical services for NASCAR. He is the author of The NASCAR Vault: An Official History Featuring Rare Collectables from Motorsports Images and Archives.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

NO SLIDES WITH THIS PRESENTATION.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

On the last Sunday afternoon in May of 1994 at the Charlotte Motor Speedway, John Andretti stepped off a helicopter, which had brought him from a tenth-place finish in the Indy 500 earlier in the day, and began his walk across the front stretch grass toward the pit road and an awaiting Chevy that he would drive in the Coca-Cola 600.

The helicopter had set down in front of a grandstand jammed with 140,000 fans, primed for the beckoning start of the 600-mile race. The fans let out a huge cheer once Andretti appeared. Now in his NASCAR driving suit, Andretti may have “bulked up” on intravenous fluids during the trip from Indy. But the moment remained enormously impressive—a lone driver, all of five-foot-five, bringing down the house by merely walking across the grass.

That was the beginning of a long and successful stint in NASCAR’s premier series for the only member of the Andretti family to work regularly in Indy cars and what was then known as the Winston Cup. He was also the only member of his clan to win the prestigious 24-hour sports car race at Daytona and to clock within a hairbreadth of 300 mph in a Top Fuel dragster.

The sports car and drag racing exploits had been accomplished before Andretti invented the Memorial Day weekend double. He teed himself up to drive an A.J. Foyt-owned Lola-Ford at the Brickyard and one of Billy Hagan’s Chevy Luminas for the 600-mile second leg in Charlotte. On the biggest day of racing in America, the diminutive Andretti won the hearts of fans everywhere. It was a calculated move by Andretti, in part, who also gained the attention of those hardened sports editors at major American newspapers who only gave racing a major space allocation on the last Sunday in May due to the huge crowds at Indy and Charlotte.

Far from a stunt, this was the real deal. People were electrified about Andretti’s arrival in Charlotte and the drama continued in a TV interview with Kenny Wallace, a relative newcomer to the broadcast side of the sport. An up-and-coming driver as well as announcer, a nervous Wallace greeted Andretti on the pit road and goofed big time by calling him “Jeff,” the name of his cousin. John took it in stride, referring in deadpan to his TV interviewer as “Rusty,” which, of course, was the name of Wallace’s older and more famous brother. It was a typical moment for the smiling Andretti, his humor undeniable and disarming, delivered in the enormous glare of the moment.

Having known him since he was 23 years old, it came as little surprise that John would eventually top that major career day in Indianapolis and Charlotte.

Andretti celebrates his first Cup win along with the Yarborough team at Daytona. Photo: Daytona International Speedway

He didn’t top it by later winning a summer Cup race at Daytona for team owner Cale Yarborough or by winning at Martinsville for team owner Richard Petty, or by winning poles at Darlington and Talladega. He didn’t top it by pursuing an ongoing bout with the Indy 500, where he raced 12 times and suffered the ill fortune that has followed the Andretti clan at the Brickyard. (Cousin Michael led the most laps of any driver who never won the race; John suffered a different type of family luck, failing to land enough rides capable of leading the field, a prerequisite to winning.)

At Indy, Andretti scored two Top 10 finishes with the Hall/VDS team in 1991 and 1992. Photo: IMS

Eventually, John would top his Indy-Charlotte double and an impressive career across multiple disciplines by how he faced the fact he was diagnosed with colon cancer in his early fifties. He stepped up big time by publicly engaging a problem faced by many who were dodging the well-known, but often shunned, method of early detection—a colonoscopy once every five years after the age of 50. By creating the hashtag #CheckIt4Andretti and speaking publicly about his illness, John knew he could make a difference.

“That’s the only reason I went public,” he later confided to a writer for a medical magazine called Coping with Cancer. “Because I really didn’t want people to know. I don’t want people to feel sorry for me.” Even now, trying to walk a mile in his shoes, it’s difficult to fathom how hard it must have been for such a proud man to publicly admit he could have avoided a painful and often deadly form of cancer by choosing the standard medical screening.

In round one, John beat the cancer following dastardly difficult surgery and chemotherapy. But as cancer often does, it returned with a vengeance. John fought bravely. We know this from the many accolades and tributes from those familiar with the final year of struggle before his death at age 56.

Andretti, aged 23, paired with Davy Jones and BMW to score his first IMSA Camel GT win at Watkins Glen in 1986. Photo: Tony Mezzacca

It was almost impossible not to like John Andretti. I had first met him while he was driving a GTP car for the BMW factory team shortly after he had graduated from Moravian College (and simultaneously raced USAC midgets at the Indianapolis Speedrome). Near the end of that 1986 season, at age 23 he scored a major victory for BMW in a co-drive with Davy Jones at Watkins Glen. Even then, Andretti had a disarming manner and was outgoing in a way that really engaged people—which he always seemed to enjoy. His perspective was his own and invariably unique, as later witnessed by his response to colon cancer.

It can be odd, sometimes, how a friendship strikes up. John had what might be described as an Italian temper as well as temperament, the latter being about a capacity for the joys of life and an individualistic viewpoint. As for the temper, it was easy to tell when John was angry. As far as I knew, it didn’t happen very often. But when angry, John lit up like a bulb. One day during an IMSA race weekend, he was considerate enough to lower the boom where nobody else could hear us. “When I read your race reports,” he said with a generous amount of heat, “it’s like you think everybody else on the team is responsible and I’m just along for the ride.”

John posted his first major victory at the Rolex Daytona 24 in 1989 with the Busby team, co-driving with Bob Wollek and Derek Bell, all the young age of 25. Photo: Peter Gloede

This conversation took place during IMSA’s 1989 GTP season when John was paired with Frenchman Bob Wollek on the Porsche 962 team owned by former star driver Jim Busby and sponsored by Miller beer and B.F. Goodrich. The team had won the season-opening 24-hour, where Derek Bell had been part of the three-man driving crew. Thinking back to when Davy Jones co-drove with John in what turned out to be the crucial stints in the BMW victory at Watkins Glen in 1986 and then considering the 24-hour win at Daytona, co-driven with Wollek and Bell, I realized John had raised a valid point.

“Brilliant” Bob, as Wollek was known, was regularly hired by factory teams for his deep understanding of tires and chassis. He had a Machiavellian way of dealing with journalists, alternating mild sarcasm with approachable friendliness and then, inevitably, angry tirades. Bell, the Brit who won his eighth 24-hour between Le Mans and Daytona that year, had an established reputation. The young Andretti, on the other hand, was still proving himself in my eyes, which I realized may have been a mistake, because I was paying too much attention to other story lines. At Daytona, this included John’s scheduled start in a sister Busby Porsche with cousin Michael and uncle Mario. That car departed early, allowing John to switch to what became the winning machine initially driven by Wollek and Bell.

“OK, John,” I told him, “I understand what you’re saying. From now on, I’ll pay closer attention.” I talked with a trusted member of the Busby team and got more details about John’s role entering the fifth race of the season. Then, John delivered. He and Wollek won that weekend on the fairgrounds circuit at West Palm Beach against a deep field of Porsches, two Jaguars entered by TWR and the Nissan of Electramotive. My story included this line: “Andretti was not only instrumental in setting up the Goodrich-shod Porsche, he nearly matched Wollek’s times in the race that ended Electramotive’s three-race winning streak.”

Although drivers make their own way, racing magazines always made an impression. That’s what John was angling for, understandably, the kind of third-party information in the media that would help him get a good ride in a CART Indy car. If John got a ride in CART, which he did, that was up to him. But I had to admit he had nailed me on initially adopting a wait-and-see attitude about him during the inevitable cacophony of GTP races with multiple contending teams and co-drivers. Had I fallen guilty to thinking he got the ride in the BMW and the Busby Porsche just because of his family name? Had I doubted his sports car endurance ability due to his diminutive size? Where his cousin and uncle were short and stout, at that time John was a similar height but slender by comparison, almost wispy at 135 pounds.

I’ve had young drivers tell me how wrong my reporting was and then declare, “I’m never speaking to you again.” They’re the type that usually sabotages their own career in equally disastrous relationships with teams and co-drivers. But after the West Palm Beach victory, John went back to being outgoing, engaging and funny whenever I saw him, bearing no hint of a grudge or the usual frostiness of drivers after swords have been crossed. As it turned out, our careers advanced along similar lines. John landed an Indy car ride in the legendary Pennzoil colors of Jim Hall, winning out of the box in Australia in 1991. I added the Atlanta Journal-Constitution to my publications list, the largest newspaper in the Southeast and the largest that regularly covered NASCAR. The paper sent me to Indy in 1991, where John joined uncle Mario, cousins Michael and Jeff in the starting field; John scored his best-ever finish of fifth in that year’s 500.

In the year of his double, I covered the final leg in Charlotte. In the previous year, the newspaper had me covering local drag racing, which meant reporting on John clocking 299 mph in the Southern Nationals at the Atlanta Dragway and winning two rounds in Top Fuel, before bowing out in the semi-final round of eliminations. At the time, John was an out-of-work, young race car driver who had taken the extraordinary step of doing something completely different to keep his name—and skills—in front of the racing community. It could not have been as easy to adapt to the high-powered, finicky Top Fuel machines.

The money soon ran out on the drag racing side, but then John landed a full-time gig in NASCAR as a result of the Indy-Charlotte double, once again taking it upon himself to call attention to his talent, stamina and media appeal, which led to 393 career Winston Cup starts, including 15 in the Daytona 500.

Looking back, John had driven in IMSA sports cars and taken the journeyman ride in Top Fuel to demonstrate his ability with high horsepower cars, which for young drivers was a prerequisite to entering the major series that included deeper fields and stiffer competition. If people thought maybe he wasn’t big enough or strong enough to handle major 500-mile races, it occurred to John how he might change the minds of potential team owners and sponsors. He could give himself a better opportunity to land a ride in either Indy cars or NASCAR if he created and pulled off the Memorial Day weekend double. We never talked about it, but looking back, it seems I was not the only one who had doubted this Andretti early in his career.

Not only did John and I continue to cross paths throughout his days in NASCAR, but I also got to know his father Aldo, the twin of Mario. Aldo frequented NASCAR events to watch John race, often getting around to various parts of the track to observe on his own. In conversations with Aldo, I could see where John got his insightful and wry view of the world. His father had suffered a head injury that forced him out of racing while Mario continued and achieved worldwide fame. Despite his misfortune, Aldo retained a generosity of spirit and ability to handle life’s fate with pride and humility, two attributes that run deep in each of the twin brothers whose fates were so disparate. Although he never achieved the considerable heights of his uncle or cousin Michael behind the wheel, John not only made his father extremely proud, but sustained those twin pillars of pride and humility.

As far as the world knows about the second half of his double in 1994, for example, the engine expired in his Chevy after 220 of 400 laps. The fact was that John hit the wall to bring out the first caution, which damaged the radiator and later the engine. He didn’t make any excuses, such as starting in the back after qualifying ninth, because he had missed the mandatory pre-race drivers’ meeting. “I was really loose,” he said. “It’s a tough job driving a loose car and I was hoping for a yellow. Unfortunately, it came out for me.” He soldiered on, eventually completing 830 miles of racing that day and night.

Once his driving career was over, John found himself in a world where racing had evolved into a TV-enriched state. Appearance fees started reaching five figures, even for retired stars. John, who always seemed to draw energy from those he engaged as well as give it, chose his own way. He continued to voluntarily raise money for the Riley Children’s Hospital, where he regularly visited with patients and their families, by promoting the “Race for Riley” go-kart event. He also helped promote son Jarett’s sprint car career.

The signature car design known as ‘The Stinger’ raised $900,000 for charity. Photo: unknown

John promoted the Indy 500 through the “Stinger” project, a modern car built in homage to the Marmon Wasp that won the first Indy 500. It was a joint effort by John, the Andretti Autosport team of cousin Michael and Window World, one of John’s longtime sponsors. When necessary, John traveled with the car around the U.S. to gain signatures of as many living Indy 500 veterans as possible, including every winner, before it was sold at auction in 2016 after the 100th running of the Indy 500, raising $900,000 for the St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis.

In another twist of fate for me, John and cousin Michael launched a go-karting facility in the Atlanta area, once again establishing a common link. After this first one closed, Mario eventually joined them and the trio later helped launch a new state-of-the-art indoor karting facility in Marietta, just up the road from Atlanta. The night of the opening, I had a car problem and missed the Andrettis by a matter of minutes after locating a back-up vehicle and dashing through the snarl of Atlanta’s rush hour. Looking back, how I wished I’d had one more chance to say hello in person away from the hectic environment of a race weekend. As it was, I later called John and talked with him about the karting business on behalf of a friend looking to get into that line of work. We had a long, engaging conversation, including talk about the ongoing “Stinger” project, because John always had time for people.

When fate called on him early, John answered with the #CheckIt4Andretti campaign. In the initial treatments, John shared his story on TV with local Indianapolis sportscaster Dave Calabro, helping to leverage his message. After an all-too-brief hiatus of cancer-free status, he and wife Nancy then focused on the private side of his medical struggle and on their children, including son Jarett and his sprint car career, and two college-age daughters. John vowed to see both daughters graduate.

John and Nancy never stopped sending out Christmas cards. They probably sent more than anybody in U.S. racing, cards that were high-quality and featured a family photo. As a result, each year I’d see their children growing up, experiencing the pride John and Nancy felt about their family while taking note of their understated religious conviction. The cards, including this year’s version that showed a smiling John, have been a yearly reminder of how John always did things his way.

(Editor’s Note: Jonathan Ingram is entering his 44th year of covering motor racing. His sixth book “CRASH! How the HANS Device Helped Save Racing” is in current release. To learn more and see excerpts, visit www.jingrambooks.com.)