The following contains excerpts from “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, and published by Octane Press, which tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

When IMSA started sanctioning GT races in 1971, the big prizes on the horizon for the organization were always the 12 Hours of Sebring and the 24 Hours of Daytona. Both events had achieved international fame by then, attracting the best and brightest drivers from Formula One, world endurance racing, USAC, and the SCCA. But for different reasons, both events were in trouble by 1973. The FIA had dictated track and safety improvements at Sebring, which led the Ulmann family to announce that the 1972 race would be the last. IMSA picked up the pieces in 1973 thanks to the backing of John Greenwood, the organizational efforts of Reggie Smith and the work of IMSA founder and president, John Bishop.

In the meantime, ever-changing FIA technical rules for world endurance racing were limiting interest and even the length of the Daytona event, which ran as a six-hour event in 1972 due to concerns that the fast prototypes from Ferrari and Alfa Romeo wouldn’t last a full 24 hours. Other manufacturers like Porsche had long decided to pull out of the event.

Once IMSA joined ACCUS in 1973, it successfully lobbied to take over organizing the 24 Hours of Daytona starting in 1974. Unfortunately, in October that year, Saudi Arabia- controlled OPEC organized an oil embargo in retaliation for United States support of Israel during the Yom Kippur war. Over the next few months, the price of oil spiked globally and long lines formed at the pumps as shortages spread. Things got so bad that a rationing system based on the last digit of license plate numbers dictated which days people could purchase gasoline.

The shortage quickly put pressure on motorsports, which some saw as the wasteful use of a now precious commodity. Recently promoted NASCAR President Bill France Jr. organized an effective lobbying campaign in Washington D.C. to keep Congress from legislating NASCAR and other sanctioning bodies out of business. He pointed out the reality that it took less energy to put on a race than to fly an NFL football team coast-to-coast. The strategy worked, but concessions had to be made during the embargo, which lasted until April of 1974. Some races were shortened such as the Daytona 500, which ran only 450 miles.

IMSA’s two major endurance races were canceled outright in 1974. Even though IMSA had become a full member of ACCUS and had won the right to sanction the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1974, the race was shut down due to the shortage; Daytona’s owners could not guarantee a supply of fuel to support the thousands of fans expected to attend the event. Sebring was canceled for similar reasons, making the Road Atlanta round the opening race of the 1974 Camel GT season. The event was stretched to 6 hours in homage to Daytona and Sebring and was won by Al Holbert and Elliott Forbes-Robinson in a 3.0 liter Porsche Carrera RSR.

George Dyer’s Porsche Carrera RSR at Daytona in 1975 at sunrise on Sunday. Yes, there used to be trees visible in the infield section of the road course. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Thus, the 24 Hours of Daytona became the opening round of the Camel GT Series in 1975 and marked the first time that IMSA sanctioned the event. A healthy field of 51 over- and under-2.5 liter GT cars started the race on Saturday, February, 1st. There were no prototypes running in IMSA at that time. Although the first All-American GT cars were beginning to be built, none showed for the twice-around-the-clock endurance event. Horst Kwech would debut the first production AAGT DeKon Monza later that year at Road Atlanta.

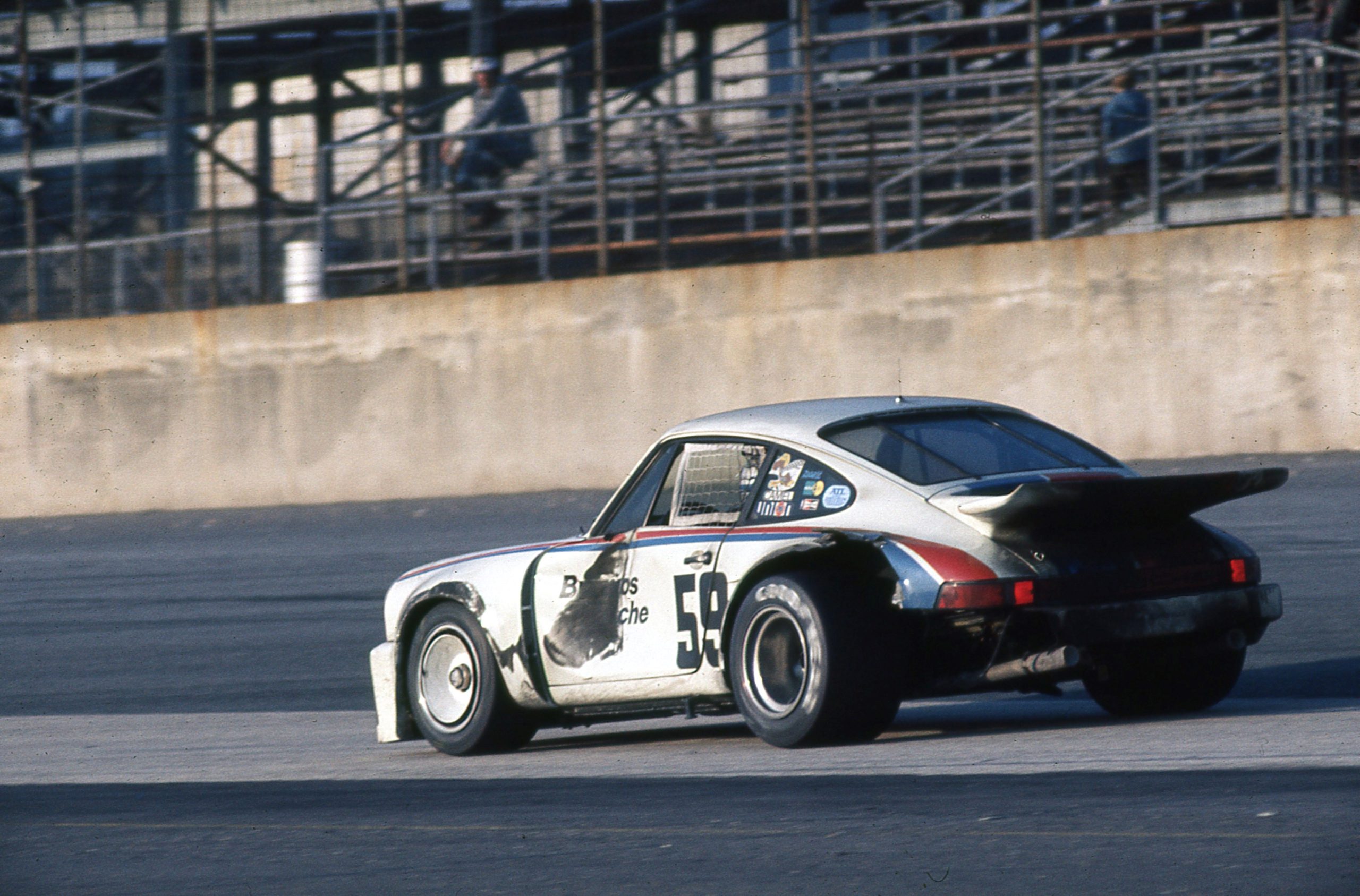

The winning Brumos Porsche Carrera RSR enters Turn One during the 24 Hours of Daytona in January 1975. Note the crash damage caused by an incident earlier in the race with Hector Rebaque that required a lengthy pit stop to repair. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Twenty-one of the entries were Porsches. By then, Porsche had been building a very successful customer car program under the direction of Jo Hoppen, the head of Porsche Motorsports USA. Hoppen aggressively drove a customer car program that became the de facto model for other manufacturers in the sport. When the International Race of Champions switched from Porsche to Camaros for the 1974 season, 15 Carrera RSRs instantly became available for IMSA racing. They had rolled off the production line at a German factory ready to race; anyone with the right-sized checkbook could buy one. The cars were sorted, reliable and fast. Hoppen placed the cars with good teams, which filled up IMSA fields for the next few years with strong entries carrying the Porsche banner. He also arranged for a fully stocked Porsche parts trailer to show up at every IMSA event, ensuring that all the teams were well supported.

John Greenwood’s Corvette was one of the Porsche antagonists. Seen here under braking for Turn One during the 1975 24 Hours of Daytona, it featured a paint scheme promoting the 12 Hours of Sebring a few weeks later. Greenwood’s big-block Corvettes with wild bodywork were fast (he won the pole for the race) but didn’t last the distance, completing just 148 laps. Photo: MarkRaffauf

In other news, one of the newcomers to IMSA at Daytona in 1975 was the first factory “super team” from Europe. Jochen Neerpasch brought the latest factory BMW CSL team to the premier IMSA series with pilots Brian Redman, Hans Stuck, Ronnie Peterson, Dieter Quester, and Sam Posey. As the U.S. market recovered from the gas crisis, BMW wanted to use racing to underscore its core marketing message: “The Ultimate Driving Machine.” The addition of BMW and top European drivers to the series also had the effect of raising the competition level significantly. A proven entity in Europe, the CSL had struggled in the U.S. in 1974 without proper factory backing.

Unfortunately, neither car finished the 1975 24 hour race, with the Redman, Petersen car dropping out after just 29 laps and the Stuck, Posey car ending up in 33rd spot. After the disappointing results against an army of Porsche Carreras, the BMW team regrouped and moved its U.S. operations deep into NASCAR country: the shops of Bobby and Donnie Allison in Hueytown Alabama. The team spent a month modifying the standard European-version of the CSL into a potent IMSA contender by removing weight, stiffening the chassis, improving engine reliability and tweaking aerodynamics. The changes worked; BMW won the 12 Hours of Sebring in March and became a contender throughout the rest of the 1975 season.

The winning factory BMW CSL of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Allan Moffat navigates the wide-open runways of Sebring in 1975 when Lockheed Constellations and Douglas DC-4s lined the course unprotected between Turns One and Two. Photo: Mark Raffauf

Against this backdrop, the 1975 Daytona 24 Hours was an all-Porsche affair. The only drama was: which Porsche would win. Peter Gregg tangled early on with the RSR that had won the Mexican round of the FIA’s World Championship of Makes the previous year. The No. 5 Café Mexico Porsche was driven at Daytona by Hector Rebaque, Fred van Beuren, and Guillermo Rojas. After the incident, both cars spent many laps in the pits to repair damage and fell back in the standings.

Peter Gregg leads the similar machine of Rebaque/Rojas/van Beuren during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1975 on Sunday morning. The two cars came together early in the race, requiring extensive repairs to both. Hurley Haywood and “Peter Perfect” came back to win with a car that was not so perfect. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Throughout the evening the Brumos car gained ground back with Gregg and Hurley Haywood alternating behind the wheel. A thick fog rolled in as the night progressed and visibility became a real issue. Haywood got into the car just past midnight for what was expected to be a three-hour stint since Gregg was never a big fan of driving at night or in lousy weather. Haywood, who had extraordinary vision, always seemed to get the nod in those conditions.

Despite the fog, Hurley kept circulating at close to qualifying speeds through the night. He drove longer than expected and probably longer than technically allowed. In the process, he dragged the battered No. 59 back onto the lead lap and eventually into the lead, the entire time his car barely visible to race control.

When asked his status by IMSA officials over the radio, he continued to report, “I can see everything fine down here on the ground,” which may or may not have been entirely true. Haywood drove an epic six hours straight, taking the lead and ultimately winning the race for the Brumos team. It would be one of five victories for each of the hall of fame drivers at the storied 24-hour event. In the end, Porsches occupied 13 of the top 15 spots in the results.

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

To many people, John Bishop became a savior in 1973. For twenty uninterrupted years, starting in 1952, the Sebring 12 Hour sports car endurance race for was held under the guidance of Alec Ulmann, one of the first members of the SCCA when it was founded in 1944. In 1950, Ulmann traveled to Le Mans to take in the sights and sounds of the 24-hour race. The experience inspired him to bring sports car endurance racing to the U.S., which he did with a six-hour race at Sebring later that year – the first such event held in America.

The Sebring track itself began life as Hendricks Army Airfield, a hastily built airport used during WWII as a training site for B-17 bomber crews. After the base was decommissioned in 1945, the airport was turned over to the local community. In the ensuing years, Ulmann convinced the airport authority to let him promote a series of races using the long runways and network of access roads as the track layout. As part of the agreement, one active runway remained in operation during the race.

The start of the first 12 Hours of Sebring in 1952. The event was the brainchild of Alec Ulmann, who organized the race on the decommissioned runways of a World War II B-17 training base. Photo: Sebring International Raceway Archives

Starting with the first 12 Hours of Sebring race in 1952, the event became a crown jewel on the international racing calendar, attracting the best and brightest drivers, manufacturers and race teams from around the world. The AAA acted as the sanctioning body for the first few years, until the organization quit the racing business after the now infamous Le Mans accident in 1955 that killed more than 80 spectators. After that, Alec and Mary Ulmann formed the Automobile Racing Club of Florida (ARCF) as an entity to produce and promote the race. Alec Ulmann was the vice president of the ARCF and also acted as race secretary for the event. The SCCA sanctioned the race from 1963 through 1972, with full backing from ACCUS and the FIA.

Nothing lasts forever, however. Years of use left the track surface broken, with large chunks of concrete regularly coming loose during events. The facilities were spartan for both competitors and spectators alike. Under pressure from the FIA to improve track safety for the ever-increasing speeds of new generation racing machines and to invest in better facilities for the growing crowds, the Ulmann family announced the 1972 running of the event would be the last. After 20 uninterrupted years, the Ulmann’s were tired and wanted to move on. Sebring appeared destined to become just another dusty footnote in racing history.

Recognizing an opportunity for IMSA to take over one of the world’s most recognized sports car events, Bishop approached Bill France Sr., the founder of NASCAR and investor in IMSA, with an idea for NASCAR to put up the money to save the Sebring race. France Sr. wasn’t convinced. According to Bishop: “Big Bill never understood why anyone would pay to see an event at Sebring, whose facilities, let’s say, fell far short of those at Daytona and Talladega.” Bishop couldn’t get his friend and partner to budge.

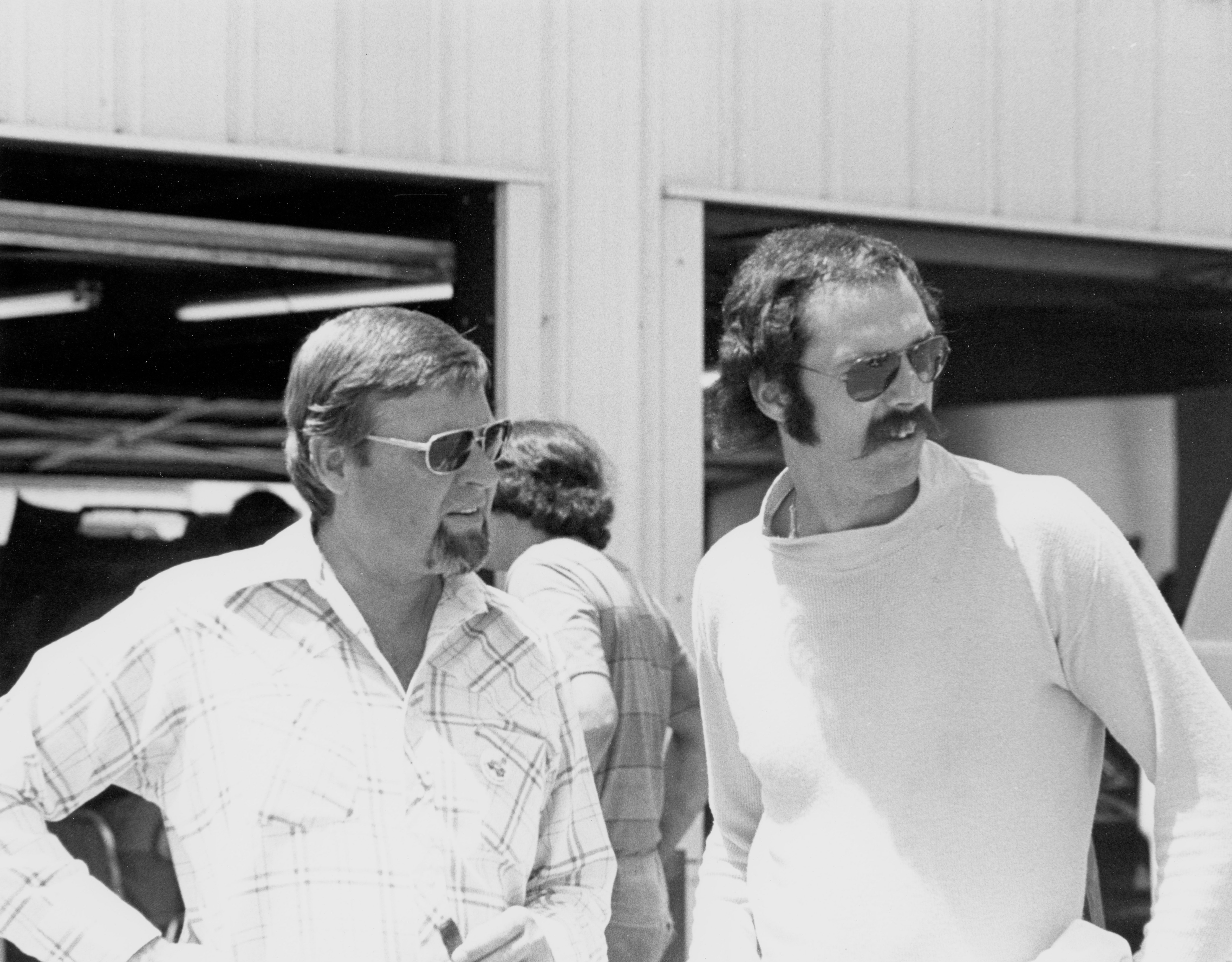

John Greenwood, on the right with Milt Minter, stepped up to bankroll the 1973 Sebring race, effectively saving the event. He would continue to be involved as a Sebring benefactor for years. IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Then, providence intervened. Bishop happened to be talking with John Greenwood about Sebring on the pit wall at Daytona in January of 1973 and to his surprise, Greenwood offered to put up the money to save the event, including making some needed safety improvements to the track like building a higher wall separating the pits from the main straight. With only a few short weeks to get it all organized and done, the pressure and the stakes were high. But Bishop recognized an enormous opportunity to elevate IMSA’s status in the racing world.

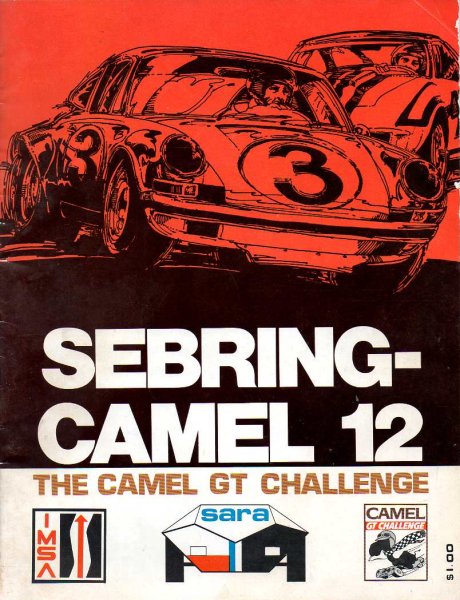

The program cover for the first IMSA-sanctioned 12 Hours of Sebring in 1973. Sebring International Raceway Archives

Reggie Smith, the ex-secretary of the ARCF, now the ex-promoter of the Sebring race, started a new organization called the Sebring Automobile Racing Association, which later on affectionately became known as the Sebring City Fathers. SARA became the official promoter of the event. Greenwood put up the prize money and made safety improvements to the track. R.J. Reynolds was more than happy to have Sebring added to the Camel GT Series calendar, which was now in its second year.

IMSA was not yet a member of ACCUS, which turned out to be a good thing, as it was not under any pressure to adhere to FIA edicts or existing ACCUS rules preventing drivers from crossing over from one member’s sanctioned race to compete in another. For unknown reasons, the SCCA board of governors voted not to interfere with IMSA taking over the race. The Club appeared to have given up on Sebring. All of this meant IMSA had a free hand to sanction an event with an almost mystical international reputation and attract drivers from any race-sanctioning body on the planet.

The runways, taxiways and access roads at Sebring have always been a challenge for racers. The Camaro shared by Luis Sereix, Tony Lilly, and Dave Voder navigates the rough pavement. Note the orange cones intended to guide the competitors at night when Sebring was pitch black and especially tricky to navigate. autosportsltd.com

The 12 Hours of Sebring became the first IMSA Camel GT event of the 1973 season. With the help of RJR’s Joe Camel advertising campaign and renewed interest in the race, a good crowd showed up, ensuring Sebring would become a fixture on the IMSA calendar for many years to come. For many people who lived through the near-extinction of the Sebring race, Bishop was recognized as one of three heroes who stepped in at the last minute to rescue this iconic event. In recognition of their contributions, Bishop, Greenwood and Smith were later inducted into the Sebring Hall of Fame.

The winning Porsche Carrera RS of Peter Gregg, Hurley Haywood, and Dave Helmick at Sebring in 1973. The traditional colors of Brumos were not used as it was Dave Helmick’s car. autosportsltd.com