by Luis Martinez

After trying to promote formula cars on ovals for its first couple of years, IMSA decided to switch its show to Grand Touring (GT) cars in 1971. The first IMSA GT race, the Danville 300, took place at Virginia International Raceway (VIR) on April 18, 1971. One of the avid spectators at the inaugural event was a U.S. Army Commanding Officer from Fort Lee, VA. The C.O. enjoyed that Sunday’s 3-hour race and the next day the Fort Lee Army Base newspaper, Fort Lee Traveller, announced the results. The C.O. discovered that one of the winning drivers of the #59 Brumos Porsche-Audi that not only won the GTU class but finished first overall was an Army conscript in his command – Army Specialist 4th Class Harris “Hurley” Haywood. Curious about this remarkable find, he summoned Haywood to present himself. When informed that he had been called, Haywood exclaimed, “Oh, (bleep)!”. Did Haywood, an active serviceman and Vietnam veteran, ask for leave to register as co-driver with racing veteran Peter Gregg? The rising IMSA Co-Champion replied with a grin: “I didn’t really ask for leave, I just sort of went.” Twenty-two year old Haywood went and chatted with his superior about the race. The C.O., realizing the talent and potential that Haywood exhibited during the race, comforted his conscript: “We have to accelerate your process-out paperwork!” How’s that for the quick application of a racing term to Army protocols?

One may ask, how did Haywood progress so quickly in life to run in front of the field for a win at the inaugural IMSA GT race? Two salient factors were in play: Haywood’s driving talent (schooled on his grandmother’s farm in Illinois), and an observant, experienced racer who recognized that talent and hired him. Haywood had often stayed at his grandmother’s farm. While there, he drove farm equipment and cars on private land learning handling techniques and getting a wheel ahead of his suburban peers. Meantime, Peter Gregg, a Harvard graduate and Navy Intelligence officer eight years Haywood’s senior, had become a successful Porsche racer. Having built an admirable racing portfolio in the middle of the 1960s, Gregg purchased an automobile dealership in Jacksonville, Florida in 1965, from Hubert Brundage – Brundage Motors. The cable address for this dealership was BRUMOS.

In the late 60’s Haywood was at college in Florida and had bought a used Corvette to compete at local autocross events. At one particular event, the experienced racer, Gregg, was also participating but the younger Haywood beat him anyway. Gregg normally won everything he entered so he decided to meet the talented youth. A friendship then ensued, a partnership that began with Gregg and Haywood collaborating to drive in the Six-Hour International Championship of Makes at Watkins Glen in 1969, winning the GT 2.0 class in Haywood’s orange #58 Porsche 911S.

But then war intervened. Haywood’s draft number came up for compulsory military service. He served a tour of duty in Can Tho, south of Saigon. While serving in Vietnam, Haywood learned a lot about situational awareness – constantly adjusting to unrelenting change while literally dodging bullets. These are lessons that he carried to podium finishes for decades as a highly successful endurance race driver.

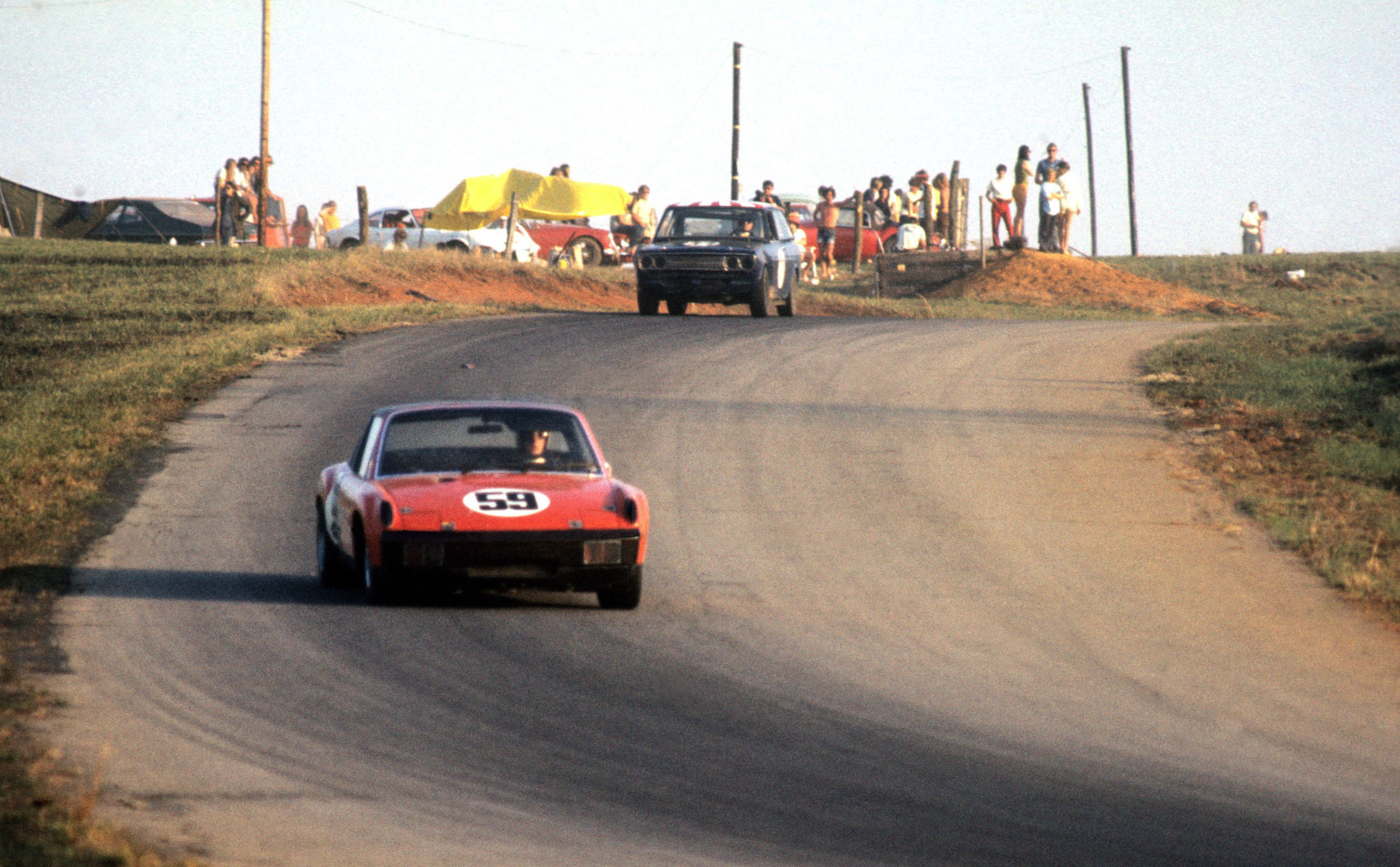

In its inaugural year, IMSA’s classification of GTU was aligned with FIA Group 2 regulations for grand touring-type cars with engines of 2.5L displacement or less (the letter U referring to “under”). With so many cars to choose from, why choose the 914-6 for 1971? Haywood responds: “The 914 GT was a ton of fun to drive. The engine is just under 2.5 liters rated at 242 hp with two Weber triple-throat carburetors. It’s caged to stiffen the chassis, and Peter drilled holes in the door panels to lighten it. It had a dry weight of 2,098 lbs with a racing suspension, a 5-speed manual transmission, and 911-type calipers. Rear tires are oversized and fit in the enlarged, squared-off wheel wells. The tires were Goodyear, 7.5 inches in front and 8.5 rear, on 15-inch wheels. With a stock capacity 16.4 gal. gas tank, the car ran in GTU. In the race, the big bore cars would run from me but I would stay on them. Going into the corners I could brake better and eventually just wore them out. It’s a giant killer.” The 914-6 had arrived from the factory as a body in white. Brumos points out that orange tangerine was Dr. Porsche’s favorite color and to pay tribute Peter Gregg chose it for his race car’s livery.

The Brumos Porsche 914-6 is seen approaching the Hog Pen corner at VIR in 1971. It was the overall winner of the first IMSA GT event ever held, beating out Dave Heinz’s more powerful Corvette in the process. Photo: Bill Oursler

The Danville 300 was actually Haywood’s third race of the 1971 season. He had already run with Gregg in the 24 Hours of Daytona where they qualified the same 914-6 in P1 but DNF’d on lap 260. A few weeks later they took the #59 car to the 12 Hours of Sebring and again qualified P1 in class and finished second in class. Haywood explains in his book, Hurley – From the Beginning, the crescendo of excitement that resulted from the win at the Danville 300: “We put the car on pole position for the class, this time starting on the front row with Dave Heinz and his 427 Corvette. That got some attention. Though the Corvette was fast and powerful, it was also heavier, with less braking power. When it started raining during the race, I found my groove and the 914 was amazing. I loved driving in the rain, especially in the perfectly balanced little car. By the end of the race we were a lap ahead in first overall, and it hit all the local papers including the Fort Lee base paper with a big photo of me on the front page.”

The car/driver combination of Porsche 914-6 GT and Gregg/Haywood proved unbeatable in IMSA GT’s first year: “ I actually owned that car when we raced it. After VIR we then went on to win our class several more times that year (Talladega, Charlotte, Bridgehampton and Summit Point) so Peter and I were co-Champions in ’71. We didn’t even bother running the 914-6 in the last race (Daytona) in November.” Haywood ran that race in a Porsche 911T.

Haywood and Gregg shared a Porsche 911S in traditional early Brumos orange at Daytona in November 1971. The car is seen here following Michal Keyser in a similar car through the infield section of the track. Photo: Bill Oursler

Haywood acknowledges in his book the positive impact that his tour of duty in Vietnam had afforded him: “The Army had changed me in ways I couldn’t have predicted. I was a calmer, more confident, cooler young man than that kid who drove at Watkins Glen in 1969. In terms of the racing itself, it was as if I never left. Instead of being rusty, my senses were sharper, my concentration more finely tuned.”

This observation about the success potential with Porsche as the ‘giant-killer’ among big-bore turned into a significant trend – from 1970 through 1984, the Porsche 917’s and other racing models accounted for 21 of the 26 overall victories in the two Florida classics – the 24 Hours of Daytona and the Sebring 12 Hours. “The 911 RSR was – and is – a great car to drive,” said Haywood, who scored three of his five overall Daytona 24-hour victories in that production-based car. “Back then, it was the car to drive because of its reliability. It was a really strong car, while the competition was not quite as reliable. The Porsche was not necessarily the fastest car on the race track, but it was certainly the most reliable.” That should settle the choice – should one go for sizzling raw power or boring reliability? Haywood is the living truth of an old saw – to finish first, you must first finish.

What happened after 1971? Haywood responds: “The 914-6 was sold and for a long time I lost track of it. I sold it to the Mexican Formula 1 racing driver, Héctor Alonso Rebaque.”

In 1972 John Bishop, co-founder of IMSA, secured a major sponsorship – R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., which put its Camel cigarette brand on the organization’s top series. As the title sponsor, the series became known as the Camel GT Challenge. Haywood remained on the roster for Brumos: “In 1972 I was given the job to run the GT car, a 911, #59 in Brumos livery and I won the championship outright.”

Over the years, the teamwork became well known, “Peter and I did so many races together, they called us Batman and Robin. We were virtually unbeatable in any car – the 914, the Carerra RSR, and the 935’s”. The driving duo lasted through the 1970s. “We had had an agreement that I would always race at least one race with Peter each year. We ran one or two races in 1979” until Gregg’s untimely death in 1980.

Besides the Danville 300 inaugural that Haywood vividly remembers, it was just two years later that ‘Batman and Robin’ registered for what became an epic race – the 1973 24 Hours of Daytona. It was in this race that the ‘dynamic duo’ unknowingly became the Porsche factory racing team. The factory had assigned two identical Porsche Carrera RSRs, which were effectively a prototype for the RSR still in development – one to Roger Penske’s team and the other to Gregg’s Brumos team. Gregg dismatled the car and noted that the flywheel was loose. He passed the information on to the Penske team but they failed to act on it. This proved to be a fatal error; Penske’s engine decomposed during the race and they DNF’d. Noting Penske’s failure Norbert Singer, then in charge of Porsche’s racing development, and his factory entourage came running to the Brumos pits which then took the mantle of ‘factory team.’ Singer then directed Gregg to tell Haywood to “slow down.” Haywood gave it only nodding attention – he had other problems – a seagull had penetrated Haywood’s windshield – literally. He needed to pit but they didn’t have a new windshield. The crew desperately “sourced” one from a spectator’s car. After the successful pit stop Haywood finished first overall. Because of that finish, the team handed the Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG factory its first international race victory using a Porsche Carrera RSR.

A single-spaced resume listing the interminable racing accomplishments by Haywood would be much longer than this article. Some of the highlights include wins at five 24 Hours of Daytona, three 24 Hours of Le Mans, two 12 Hours of Sebring, two IMSA GT championships, and one Trans-Am championship. Incredibly, Haywood started at the 24 Hours of Daytona a total of forty (40!) times by the time he retired in 2012.

Hurley Haywood at a Grand-Am event at Watkins Glen in 2010. Photo: Luis A. Martinez

But what happened to the #59 car, the tangerine orange Porsche 914-6 GT? “After I sold it to Rebaque’s father I lost track of it. Someone found it years later in 1988 in a field in Mexico. There are many 914’s out there but they called us about it. We sent our crew chief to confirm and we were able to positively identify it because Peter and I had drilled the door braces to lighten the car.” The Brumos team has meticulously restored the #59 car to its original specs and it now resides with the Brumos Collection in Jacksonville, FL.

Recent photos of the restored Brumos Porsche 914-6 at Amelia Island (photo credits: Anthony J. Bristol):

– Luis A. Martinez

The following contains excerpts from “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, and published by Octane Press, which tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

When IMSA started sanctioning GT races in 1971, the big prizes on the horizon for the organization were always the 12 Hours of Sebring and the 24 Hours of Daytona. Both events had achieved international fame by then, attracting the best and brightest drivers from Formula One, world endurance racing, USAC, and the SCCA. But for different reasons, both events were in trouble by 1973. The FIA had dictated track and safety improvements at Sebring, which led the Ulmann family to announce that the 1972 race would be the last. IMSA picked up the pieces in 1973 thanks to the backing of John Greenwood, the organizational efforts of Reggie Smith and the work of IMSA founder and president, John Bishop.

In the meantime, ever-changing FIA technical rules for world endurance racing were limiting interest and even the length of the Daytona event, which ran as a six-hour event in 1972 due to concerns that the fast prototypes from Ferrari and Alfa Romeo wouldn’t last a full 24 hours. Other manufacturers like Porsche had long decided to pull out of the event.

Once IMSA joined ACCUS in 1973, it successfully lobbied to take over organizing the 24 Hours of Daytona starting in 1974. Unfortunately, in October that year, Saudi Arabia- controlled OPEC organized an oil embargo in retaliation for United States support of Israel during the Yom Kippur war. Over the next few months, the price of oil spiked globally and long lines formed at the pumps as shortages spread. Things got so bad that a rationing system based on the last digit of license plate numbers dictated which days people could purchase gasoline.

The shortage quickly put pressure on motorsports, which some saw as the wasteful use of a now precious commodity. Recently promoted NASCAR President Bill France Jr. organized an effective lobbying campaign in Washington D.C. to keep Congress from legislating NASCAR and other sanctioning bodies out of business. He pointed out the reality that it took less energy to put on a race than to fly an NFL football team coast-to-coast. The strategy worked, but concessions had to be made during the embargo, which lasted until April of 1974. Some races were shortened such as the Daytona 500, which ran only 450 miles.

IMSA’s two major endurance races were canceled outright in 1974. Even though IMSA had become a full member of ACCUS and had won the right to sanction the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1974, the race was shut down due to the shortage; Daytona’s owners could not guarantee a supply of fuel to support the thousands of fans expected to attend the event. Sebring was canceled for similar reasons, making the Road Atlanta round the opening race of the 1974 Camel GT season. The event was stretched to 6 hours in homage to Daytona and Sebring and was won by Al Holbert and Elliott Forbes-Robinson in a 3.0 liter Porsche Carrera RSR.

George Dyer’s Porsche Carrera RSR at Daytona in 1975 at sunrise on Sunday. Yes, there used to be trees visible in the infield section of the road course. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Thus, the 24 Hours of Daytona became the opening round of the Camel GT Series in 1975 and marked the first time that IMSA sanctioned the event. A healthy field of 51 over- and under-2.5 liter GT cars started the race on Saturday, February, 1st. There were no prototypes running in IMSA at that time. Although the first All-American GT cars were beginning to be built, none showed for the twice-around-the-clock endurance event. Horst Kwech would debut the first production AAGT DeKon Monza later that year at Road Atlanta.

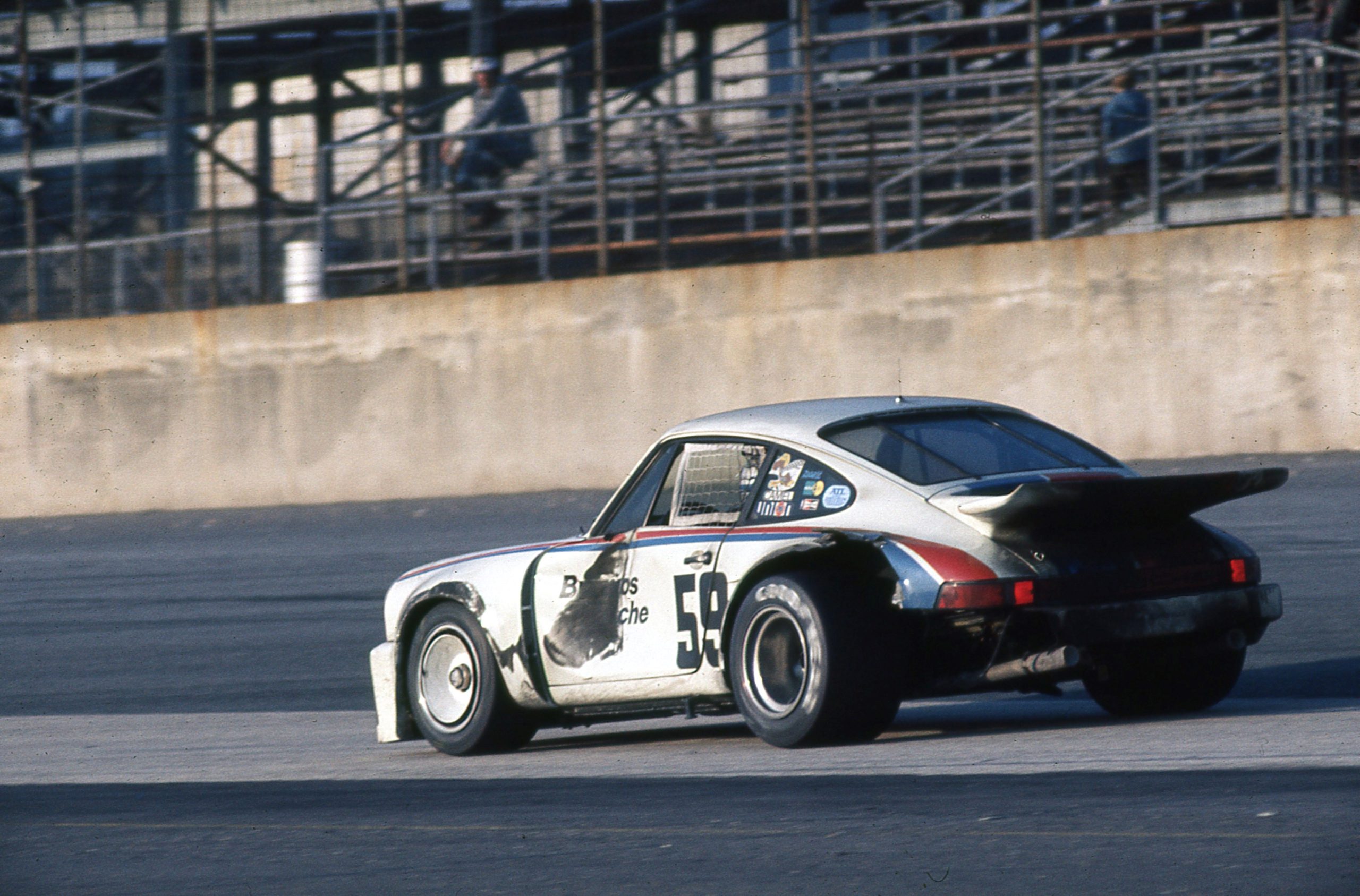

The winning Brumos Porsche Carrera RSR enters Turn One during the 24 Hours of Daytona in January 1975. Note the crash damage caused by an incident earlier in the race with Hector Rebaque that required a lengthy pit stop to repair. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Twenty-one of the entries were Porsches. By then, Porsche had been building a very successful customer car program under the direction of Jo Hoppen, the head of Porsche Motorsports USA. Hoppen aggressively drove a customer car program that became the de facto model for other manufacturers in the sport. When the International Race of Champions switched from Porsche to Camaros for the 1974 season, 15 Carrera RSRs instantly became available for IMSA racing. They had rolled off the production line at a German factory ready to race; anyone with the right-sized checkbook could buy one. The cars were sorted, reliable and fast. Hoppen placed the cars with good teams, which filled up IMSA fields for the next few years with strong entries carrying the Porsche banner. He also arranged for a fully stocked Porsche parts trailer to show up at every IMSA event, ensuring that all the teams were well supported.

John Greenwood’s Corvette was one of the Porsche antagonists. Seen here under braking for Turn One during the 1975 24 Hours of Daytona, it featured a paint scheme promoting the 12 Hours of Sebring a few weeks later. Greenwood’s big-block Corvettes with wild bodywork were fast (he won the pole for the race) but didn’t last the distance, completing just 148 laps. Photo: MarkRaffauf

In other news, one of the newcomers to IMSA at Daytona in 1975 was the first factory “super team” from Europe. Jochen Neerpasch brought the latest factory BMW CSL team to the premier IMSA series with pilots Brian Redman, Hans Stuck, Ronnie Peterson, Dieter Quester, and Sam Posey. As the U.S. market recovered from the gas crisis, BMW wanted to use racing to underscore its core marketing message: “The Ultimate Driving Machine.” The addition of BMW and top European drivers to the series also had the effect of raising the competition level significantly. A proven entity in Europe, the CSL had struggled in the U.S. in 1974 without proper factory backing.

Unfortunately, neither car finished the 1975 24 hour race, with the Redman, Petersen car dropping out after just 29 laps and the Stuck, Posey car ending up in 33rd spot. After the disappointing results against an army of Porsche Carreras, the BMW team regrouped and moved its U.S. operations deep into NASCAR country: the shops of Bobby and Donnie Allison in Hueytown Alabama. The team spent a month modifying the standard European-version of the CSL into a potent IMSA contender by removing weight, stiffening the chassis, improving engine reliability and tweaking aerodynamics. The changes worked; BMW won the 12 Hours of Sebring in March and became a contender throughout the rest of the 1975 season.

The winning factory BMW CSL of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Allan Moffat navigates the wide-open runways of Sebring in 1975 when Lockheed Constellations and Douglas DC-4s lined the course unprotected between Turns One and Two. Photo: Mark Raffauf

Against this backdrop, the 1975 Daytona 24 Hours was an all-Porsche affair. The only drama was: which Porsche would win. Peter Gregg tangled early on with the RSR that had won the Mexican round of the FIA’s World Championship of Makes the previous year. The No. 5 Café Mexico Porsche was driven at Daytona by Hector Rebaque, Fred van Beuren, and Guillermo Rojas. After the incident, both cars spent many laps in the pits to repair damage and fell back in the standings.

Peter Gregg leads the similar machine of Rebaque/Rojas/van Beuren during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1975 on Sunday morning. The two cars came together early in the race, requiring extensive repairs to both. Hurley Haywood and “Peter Perfect” came back to win with a car that was not so perfect. Photo: MarkRaffauf

Throughout the evening the Brumos car gained ground back with Gregg and Hurley Haywood alternating behind the wheel. A thick fog rolled in as the night progressed and visibility became a real issue. Haywood got into the car just past midnight for what was expected to be a three-hour stint since Gregg was never a big fan of driving at night or in lousy weather. Haywood, who had extraordinary vision, always seemed to get the nod in those conditions.

Despite the fog, Hurley kept circulating at close to qualifying speeds through the night. He drove longer than expected and probably longer than technically allowed. In the process, he dragged the battered No. 59 back onto the lead lap and eventually into the lead, the entire time his car barely visible to race control.

When asked his status by IMSA officials over the radio, he continued to report, “I can see everything fine down here on the ground,” which may or may not have been entirely true. Haywood drove an epic six hours straight, taking the lead and ultimately winning the race for the Brumos team. It would be one of five victories for each of the hall of fame drivers at the storied 24-hour event. In the end, Porsches occupied 13 of the top 15 spots in the results.