The first purpose-built, closed-course, road circuit at Watkins Glen, opened on a glorious, chilly autumn weekend in mid-September 1956, welcoming 118 racers to compete in six race events during the 9th Annual International Sports Car Grand Prix. The circuit, which has since hosted nearly every major racing series over more than six decades, almost did not open at all.

The efforts by the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation – up to the 11th hour – to ready the 2.3-mile track in time for the race weekend were extraordinary. A successful “wave the green fag” bond campaign in the local community raised initial start-up funds for the project in a single month. Contractors broke ground in late July and, after delays caused by heavy rains and unfavorable weather, completed the final touches on the asphalt paving only an hour before practice sessions began. Alterations to one of the curves, using earth-moving equipment under the glare of spotlights, were made during the night before the first race. And then officials from the Sports Car Club of America jeopardized the entre event by withdrawing their recommendation for members to participate at the last minute due to what they deemed the “serious and hazardous conditions of the course.”

Despite official concerns, not a single driver willingly withdrew from competition. A crowd exceeding 30,000 spectators enjoyed the “European carnival aspects” of the weekend and watched a “thrilling race” across the fast and tricky course as George Constantine of Sturbridge, Massachusetts in his D-Type Jaguar took the checkered fag for the Sports Car Grand Prix.

The IMRRC

With a mission to “To collect, preserve and share the global history of motorsports,” The International Motor Racing Research Center, located at Watkin’s Glen, New York, has, since 1996, been a place open to historians and to the general public and preserves an ever-growing collection that documents the history of racing in the more than 4000 books, 250 different motorsports magazines and newspaper titles, club and sanctioning body records, race results, programs and posters, papers of motorsports journalists and scholars, correspondence of race organizers and still and moving images. Its knowledgeable research and archives staff assists hundreds of scholars, journalists, authors, documentary film makers, drivers and race car owners from all over the globe with inquiries about motorsports history every year. It relies on gifs and donations from the motor sport community. See www.racingarchives.org.

Download the Original Article.

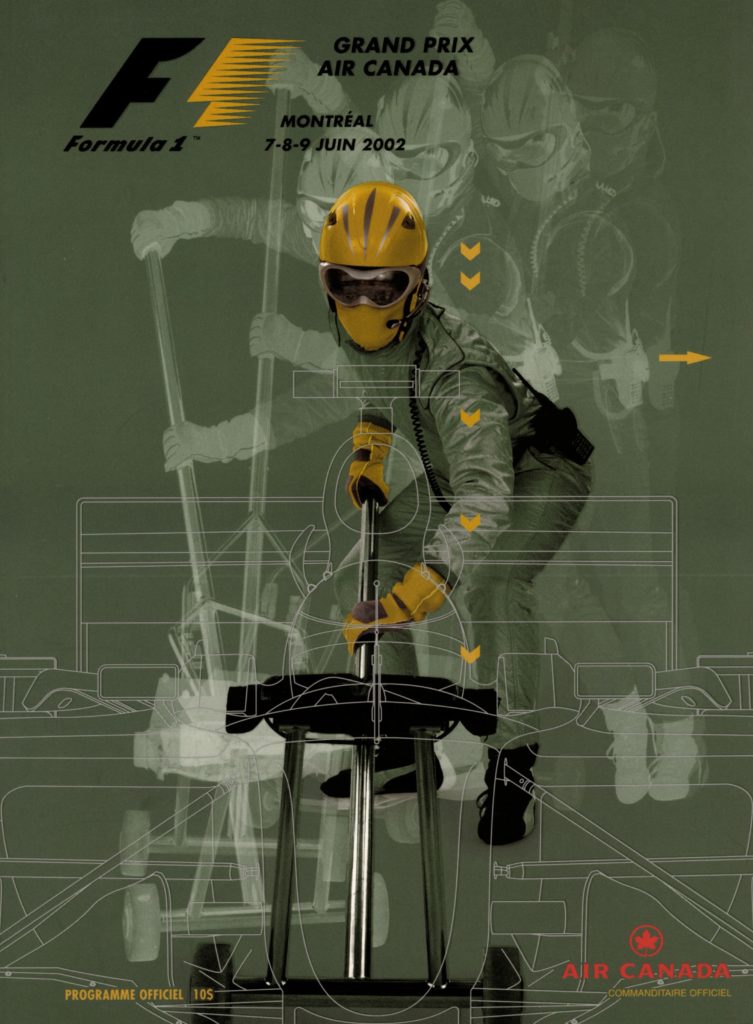

Founded in memory of David Chandler of Olive Bridge, NY, this Memorial Fund is the perfect way to honor a friend or loved one’s memory while celebrating their enthusiasm for Formula One.

Founded in memory of David Chandler of Olive Bridge, NY, this Memorial Fund is the perfect way to honor a friend or loved one’s memory while celebrating their enthusiasm for Formula One.

David’s friend, Stewart Long, wrote a letter in his memory for the start of the fund:

“Dave and I attended about 10 Formula One Grand Prix races in Montreal from the early 1990s through the mid-2000s, during which time we became fast friends by sharing our interests as Formula One fans.

We would arrive at Circuit Gilles-Villeneuve as soon as the gates opened, stay all day, and be among the last to leave. We saw everything: the mechanics opening the garage doors and warming up the cars, working on the cars, the cars on the track. We spotted drivers, team managers, and celebrities in the pits. We were there the first year Michael Andretti was in Formula One and put up a banner in the stands that said, ‘USA Supports Andretti.’ It was reported on by one of the French newspapers, so we shared our 15 minutes of fame together.

Dave was a pure and passionate enthusiast. He was a huge fan of Ayrton Senna, the brilliant driver from Brazil with exquisite car control skills and a three-time world champion. He even had a Senna tee shirt with the famous and stylistic Senna ‘S’ on it. One year, as usual, I waited outside the pits (after Dave had left since he had to drive back that evening to go to work on Monday) to see the drivers as they left. To my great pleasure, Senna came by and stopped to sign autographs. I was in a line of about eight people and thought, ‘Wow, I’m going to be able to get my program signed by Dave’s ultimate driver, and won’t he be thrilled when I send that to him.’ Unfortunately, Senna waved and moved on when I was only two people away from him. So close. Still, Dave and I shared that story many times so it had positive benefits in that regard.

Dave was a great friend and racing enthusiast. He will be deeply missed by his family, colleagues, and friends. His spirit as a Formula One fan will live on in this Memorial Fund.”

To read the complete letter, click here.

Make a contribution to the Formula One Fan Memorial Fund. Leave a note in the description box that says Formula One Memorial Fund, and the name of who you’d like to honor. You can also send a check made out to IMRRC at 610 South Decatur Street, Watkins Glen, NY, 14891.

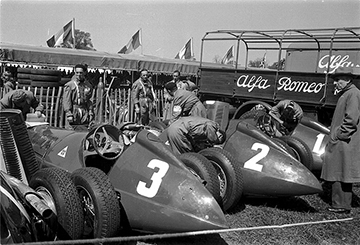

This past weekend was the 1000th Grand Prix of the modern era of Formula 1, held at Shanghai in China. Today let’s take a look back at some photographs from the first Grand Prix of this era. It was the British Grand Prix which also had the title of Grand Prix d’Europe and took place at Silverstone on May 13, 1950. In 1950 Alfa Romeo was the leading team with their 158 which was an update of a prewar design. Car number 1 in front of the lineup in the rudimentary Silverstone pits of the four Alfettas will be driven by Juan Manuel Fangio. Other Alfa drivers will be Giuseppe “Nino” Farina, Luigi Fagioli and British garagiste Reg Parnell.

Before the race started, King George VI (in the grey suit) greeted the drivers. Here he is speaking with Louis Chiron as Toulo de Graffenried awaits his turn and Prince Bira leans in patiently at the right. The Royal Family would watch the race from a small private elevated stand.

The Silverstone paddock was directly behind the pits and was pretty informal being simply a mown field inside the runways of the old RAF wartime airfield. Here again, is the Alfa Romeo team with car number 4 to be driven by Reg Parnell.

Here is another view of the Alfettas in the paddock with the pits in the background and the Alfa Romeo transporters at the right. Car number 3 will be driven by Fagioli and number 2 by Farina.

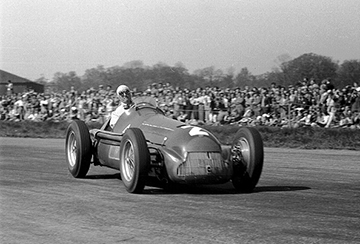

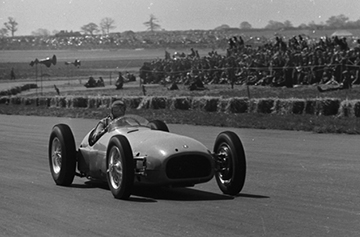

And here is Farina with his imperious driving position on the approach to Stowe Corner at the far end of the circuit. He swapped the lead at various times during the race with Fangio and Fagioli. Parnell was driving somewhat cautiously being a guest driver for the great Italian team.

The Talbot Lago 26C was really an open-wheeled sports car design of which there were five examples entered, two by Antonio Lago’s Automobiles Talbot-Darracq and three by private teams. This example was a Talbot team entry piloted by the French prewar driver Eugène Martin. He did not finish.

Monégasque Louis Chiron was a famous prewar driver who eventually became the oldest driver to start a Grand Prix when he drove a Maserati 250F at Monaco in 1958. At Silverstone, he was already 50 and drove a factory-entered Maserati 4CLT/48 but failed to finish.

In another Maserati 4CLT/48 was English amateur driver David Hampshire whose car was entered by Scuderia Ambrosiana. This Italian private team, created by Giovanni “Johnny” Lurani, allowed English drivers to maintain racing cars outside of England and thereby avoid both Purchase Tax and, by swapping expenses, the then limitation on taking Sterling funds outside of England.

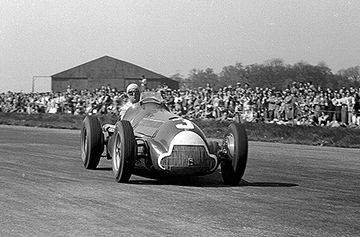

This is Fagioli seen braking for Stowe Corner with his Alfetta. He would finish second to Farina after Fangio hit a straw bale and then suffered engine failure.

Before the start of the Grand Prix, Raymond Mays drove a slow demonstration lap in the B.R.M. 15 which was not yet ready to race after numerous disappointments. Here he is coming out of Abbey Corner and past the pits which at this time were located between Abbey and Woodcote.

The race is over and the Alfa Romeo mechanics surround Reg Parnell’s third-place car as he heads to the prize-giving. The smashed grille in its nose resulted from a fatal argument with a hare during the race. There was no other damage caused by the collision.

Nino Farina receives his laurels as the winner of the first Grand Prix counting for the World Championship which he will go on to win in 1950.

The winner and World Champion to be, Nino Farina

Photos by Alan R. Smith & Louis Klemantaski ©The Klemantaski Collection – http://www.klemcoll.com

Back in 1974 at Watkins Glen for the United States Grand Prix, I got the chance to sit down with Mario Andretti – in the Vel’s Parnelli Jones team’s section of the Glen circuit’s Technical Centre – and hear from him about his life and career that far. Mario came across as a hyper-competitive sportsman of great – and continuing – achievement and experience and, as a man, he was friendly and engaging and one who conducted himself in a gently distinguished (and highly impressive) manner.

To me, as a hopeless race reporter – by temperament far too shy and reserved ever to ask questions of anyone to whom I had not yet been introduced – the time Mario gave me that day seemed incredible. How had I got to him? Well, both Vel’s Parnelli designer Maurice Phillippe and team manager Andrew Ferguson were fellow Brits, ex-Team Lotus in England.

I knew both well from Lotus days, and it was Andrew who overcame my natural reticence – called me over and said “Hey Mario – here’s someone you ought to meet – he’s OK”. So, there at the Glen that day, I taped a long conversation with America’s finest Italian-born racing driver. And here’s part two of the feature story based upon it that I put together over the next few days. – Doug Nye

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Continued from Part One…

The 1965 USAC big car season opened at Phoenix, Arizona, where Mario punched Dean’s lightweight roadster into the lead ahead of all the Lotus-based rear-engined cars. Then Johnny Rutherford spun in front of him and set him back to finish sixth.

Meanwhile, Clint Brawner had done a deal with John Zink, owner of the first Brabham Indy car, to copy it and build two updated Ford V8-powered replicas; one for the Dean team and one for Zink’s. The car was built, and it had scarcely turned a wheel before Andretti ran it so successfully at Indy. He went there with a second place at Trenton under his belt, and his fearless performance at the Speedway, swooping up within inches of the retaining wall out of the high-speed turns, finally made his name. It was Mario’s psychology which was right.

“Indy was, and is, a big myth in everybody’s mind. All the old-timers there look at ya and say ‘OK kid, don’t get too cocky, this is Indy’. So you think about it and you sit down and then you think ‘Shit, I’m not gonna get psyched. This is just a speedway like any other’. So you get prepared and you get it right and you do it right. Indy is special because everybody knows about it—you can’t do things there quietly—but otherwise, the Indy thing is a myth.

“What’s more difficult on the Championship circuit? I tell you, Trenton’s more difficult now. It’s 1½-miles and they’ve got a right-hand dogleg curve in the back-stretch. That dogleg’s a pig ’cos the cars can’t be set-up for it. You’ve gotta be so right through there. . .”

After his third place at Indy, which earned him $42,500, Mario won the Hoosier Grand Prix, was second in five more races and won the USAC Championship with 3,110 points. It had been his first full season, and he was the Rookie Champion. He was only 25 years old.

Mario Andretti circa 1966. Photo by Bernhard Cahier

In 1966, he won the title again, winning eight of the 15 qualifying races outright. At Indy, he qualified squarely on pole position with a new four-lap average of 165.899 mph and a one-lap record of 166.238 mph. He led for the first 16 laps until sidelined by valve trouble, to be classified a sorry 18th. Otherwise, his domination was complete.

Versatility is Andretti’s keynote. “I never retired from any form of racing’, he says, and early in 1967 he made his debut in NASCAR racing, taking on a Holman and Moody Ford Fairlane in the magic Daytona 500. He qualified for the race at a better than average 177 mph, but it was nothing startling. Then late in practice his red and grey Fairlane stormed around at 182 mph and some of the skeptical NASCAR faithful took a second look at the little man from Pennsylvania.

After a fierce late-race duel with Fred Lorenzen, it was Andretti who stormed to win the 500 —the first USAC and first non-NASCAR driver to do so. ‘Tis said that Kate Firestone was astonished by the man. “Look at him, he’s so teensy!”, she said. The Detroit News commented sagely, “…He’s toughsy and fastsy too…”.

Mario is one of the very few drivers ever to win the Indianapolis 500 (1969) and the Daytona 500 (1967) in their careers. He’s pictured here in the winning machine at Daytona.

Road racing was the next field to conquer. Mario had run a NART Ferrari in the Sebring 12-Hours the previous year, but a tragedy-darkened run ended in retirement. For ’67 he was paired with Bruce McLaren in the prototype 7-litre Ford Mark IV, and they won. Next day he was in Atlanta, running another 500-mile stock car race until repeated tyre blow-outs snuffed-out his drive against the wall. At Le Mans, he was paired with Lucien Bianchi, and their big Ford was running in second place in the small hours when the Belgian brought it in for refueling and a routine brake pad change.

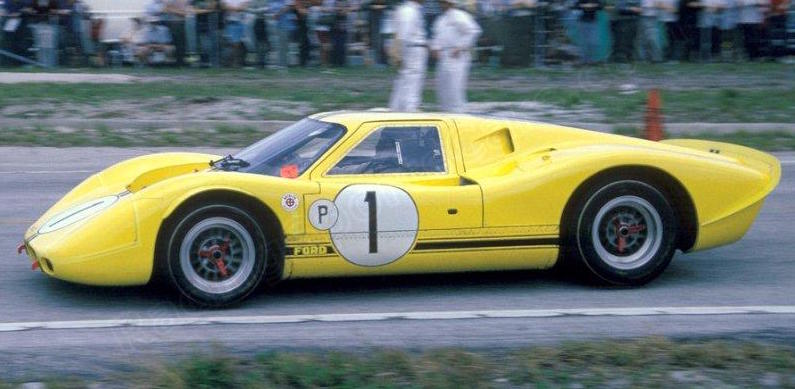

The team of Bruce McLaren and Mario Andretti won the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1967 driving this prototype of the Ford GT 40 MkIV. Photo: George Boron.

It was then that Mario had one of his biggest frights; “The pads went in backward and cracked the disc. As I braked down into the Esses, right out of the pits, they just jerked the wheel out of my hands and the bitch car hit just about everything. I got to the side of the road when Roger McCluskey appeared, thought I was still in the wreck and smashed up trying to avoid it. Then Jo Schlesser came over the top and smashed his Ford as well oh, what a bitch that was…”.

Indy that year had Andretti on pole for the second time, but he was out of the race when the right front wheel parted company. He won seven Championship rounds and was leading the Rex Mays race at Riverside with only three laps to go when a stop for fuel cost him victory, and what would have been his hat-trick of National titles. Instead, A. J. Foyt topped the ratings.

In December Al Dean died, and Andretti took over the racing stable himself, still with Clint Brawner and Jim McGee preparing the Championship cars. Indy was a disaster as he started from row two and became the first retirement after only two laps, with engine trouble. He fought back in the rest of the series, winning three times and placed second 11 times. But the Riverside race cost him the title again, this time to Bobby Unser, by only 11 points. On road circuits, he had driven for Alfa Romeo at Daytona, and then Colin Chapman offered him a Gold Leaf Team Lotus drive in the Italian and US GPs. He was ruled out of the Italian race because he had a USAC event to do within 24 hours, but at Watkins Glen, he shook everybody by taking pole position in his first Formula 1 race. It all fell apart when the car’s nosecone fell to bits and its clutch failed.

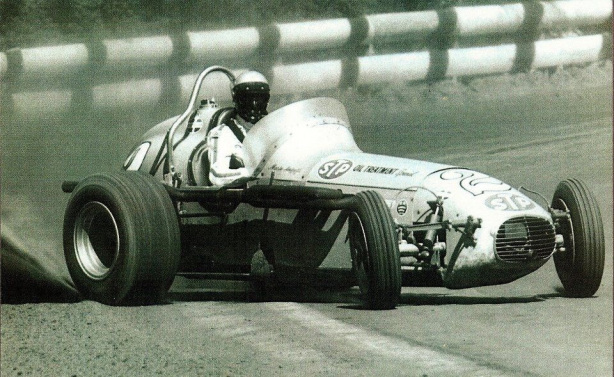

Mario Andretti poses with the STP-sponsored team owned by Andy Granatelli (far right) that won the 1969 Indianapolis 500.

Then came 1969, backing from Andy Granatelli and STP and a first win in the Indy 500. During practice, Mario crashed very heavily in the Lotus 64, and he raced his ancient Hawk-Ford. “It was just a spare car you know, not even cleaned-off since Hanford. It had just two days of practice and was never out of third. I had to back-off in the race, it showed 260-degrees oil temperature, but we won. It was the first time … it was very satisfying”.

He went on to win eight more races and his third Championship. A works Ferrari ride into second place at Sebring meant a lot to him and with a brutish McLaren-Ford he struggled manfully to two good CanAm sports car placings. Meanwhile, he had great faith in four-wheel drive, and Colin Chapman pinned his Formula 1 hopes on the American’s faith. Unfortunately, “… it was worth a try, but it proved absolutely not worthy of road racing. Tyre development solved the traction problem, and anyway, the car’s straightaway speed was down. In a high-speed corner, the things were just fantastic, which is why they worked at Indy, but otherwise, no way…”.

At the Nurburgring, Mario had a short German GP. “I’d never practised with full tanks, an’ then I got a good start and was up with them. But the thing was bottoming on the bumps and then up over that Flugplatz, it bottomed so bad, I caught a wheel on the catch fence and took it off. I didn’t crash, I just slid to a stop but then Vic Elford came over in that McLaren and hit the wheel. He rolled upside down over a drop and I went down and held the car up off his arm on my shoulder and reached in and knocked the switches off. Poor guy, I felt kind of responsible, but what can you do, you know?”

In 1970 Mario was back in a Ferrari, this time a 512 in which he helped Vaccarella and Giunti to win at Sebring. The Granatellis backed him in the ill-conceived McNamara Championship car and in a similarly unsuccessful Formula 1 March. He was fifth in the USAC National Championship, which for him was a big fall. Then came the Formula 1 signing with Ferrari for 1971. “I enjoyed that to no end. It was something I had dreamed of since I was a kid at Lucca and when I won in South Africa it was the most satisfying thing I’d ever achieved.

“Psychologically it was a very great thing, and the win at Ontario was good too because those cars were the real t’oroughbreds. It’s who you beat that matters—I’ll take wins any way they come—but to be in front of Stewart both times was great…”

That season was his last with the Granatellis (“I’m still personally good friends with Andy, but I couldn’t agree with the way things were done there, those brothers, you know?”).

He was put out of Indy in an early four-car crash, and second at Trenton was his best finish of the year. He was ninth in the point standings and left the STP fold to join Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones for 1972.

“That Vel…”, he says, indicating the big-built greying Californian motor dealer smiling happily beside his Formula 1 car, “… he’s such an ent’usiast you can’t believe it. I wanna race and be competitive and that’s why I joined Vel’s — they’re 200 percent…”

The Maurice Phillippe-designed Viceroy Special which Mario drove was not as competitive as had been hoped. “But the biggest problem with the car was its big build-up. First time we ran we had news people crawling all over it, and when it wasn’t quite right we got all the crap, you know. I could’ve killed that PR man!”

Most of Mario’s winning that season was with the Ferrari sports car team, partnering Jacky lckx, for they took the Daytona, Sebring and Brands Hatch Championship rounds. “I enjoyed that long-distance racing, it disciplines you to go quick without destroying the car”, while in USAC “I led nearly every race only to blow engines. We had a piston problem…” That was expensive, as at Indy where Mario’s detuned car was fifth at 190 laps only to run out of fuel and be placed eighth. Team-mate Joe Leonard ran his identical Samsonite Special more slowly and gained in reliability to win the Championship.

The winning Ferrari 312PB (#0888) of Mario Andretti and Jackie Ickx at Daytona in 1972. The race was shortened to 6 hours that year. The pair would repeat at Sebring two months later. (Photo: Levetto)

The ’73 season saw Vel’s Parnelli using re-designed Phillippe cars in which Andretti won early on at Trenton, and set a world’s closed-circuit outright lap record at Texas World Speedway. Thereafter fortunes again took a dive, in European eyes it seemed as though Andretti was running out of steam, we didn’t hear much of him any more…

Then in April this year, he shared the winning Alfa Romeo in the Monza 1,000 Kms, at the seat of Italian motor racing. That must have meant a lot? “Yeah, that was OK, but it was sports cars, and who did we beat? The Grand Prix …” a faraway look at the Parnelli car “…would be different”.

The ’74 Parnelli USAC car put in just one race, at Trenton, where Mario put it on pole and led until the engine failed. Vel’s Parnelli wheeled a Formula A/5000 Lola into their Torrance, California, workshops, and Mario took it out on to the American Championship road circuits, winning at Elkhart Lake, Watkins Glen and Riverside. “ On a road circuit Mario is as sharp as ever”, they said, and when it came to the team’s Grand Prix debut with their brand-new “… four-inch lower Lotus 72” he proved it.

“Formula 5000 has become good racing,” he says reflectively, “… and lucrative too, with purses of $55,000-60,000 for the races, and $16,000-18,000 for a win. But that Brian Redman, you know, he has been really tough competition, fantastically quick. Jim Hall’s operation too, they’re tough. But it’s good practice for Formula 1, and this is where I wanna be. I figure I’m not getting’ any younger, and I’m trying to do it seriously now. Next year I’m gonna do Formula 1, 5000 and the three 500-mile track races, I guess that’s enough…”

Andretti is married, has two sons and a small daughter, and still lives in Nazareth where they have named a street (Victory Lane) in his honour. His last Fl race previous to the Vel’s Parnelli venture was the Glen in ’72 when his Ferrari was placed sixth and at least some of the fans recalled that. While we were talking a teenaged kid came bursting in, eyes aflame with enthusiasm (if not much knowledge). “ Hey, Mario, I’m looking for ya, man. You racin’ this afternoon? What ya drivin’? Ya drivin’ Lotus? Ya drivin’ Ferrari?” etc, etc. Andretti’s natural reaction was “ thanks, but excuse us, we’re talking here”, slowly changing to muted irritation as the kid’s ignorance showed. He eventually backed off moaning “Hey Mario, man, I was lookin’ for ya, man…lookin’ for ya…” to be swallowed up in the crowd.

Mario Andretti turned his powerful shoulders, brown eyes darkened; “That kinda thing bugs the bell outa me”, he snorted, “…but I guess he’s got ent’usiasm”, and his tanned face creased into a grin. Maybe he was thinking where his “ent’usiasm” has put him, and next season he’s going to be running hard to improve on that.

“At Mosport, we had a little rev problem, and were over-winged, but we hung in there for seventh. Here we’ve learned a little more. We were getting it all to work for us until that pump died on the start, and we got disqualified. But that’s racing, you know… Hopefully, we can make it a better car yet, and really, it’s so good to be here again in Formula 1, it really is. It’s the thoroughbred of racing, you know it’s the top…” Mario Andretti, Watkins Glen, October 1974.

Mario Andretti wheels the Vel’s Parnelli Jones Formula One car at Watkins Glen in 1974. Photo: International Motor Racing Research Center.

Back in 1974 at Watkins Glen for the United States Grand Prix, I got the chance to sit down with Mario Andretti – in the Vel’s Parnelli Jones team’s section of the Glen circuit’s Technical Centre – and hear from him about his life and career that far. Mario came across as a hyper-competitive sportsman of great – and continuing – achievement and experience and, as a man, he was friendly and engaging and one who conducted himself in a gently distinguished (and highly impressive) manner.

To me, as a hopeless race reporter – by temperament far too shy and reserved ever to ask questions of anyone to whom I had not yet been introduced – the time Mario gave me that day seemed incredible. How had I got to him? Well, both Vel’s Parnelli designer Maurice Phillippe and team manager Andrew Ferguson were fellow Brits, ex-Team Lotus in England.

I knew both well from Lotus days, and it was Andrew who overcame my natural reticence – called me over and said “Hey Mario – here’s someone you ought to meet – he’s OK”. So, there at the Glen that day, I taped a long conversation with America’s finest Italian-born racing driver. And here’s the feature story based upon it that I put together over the next few days. – Doug Nye

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

It took just under four minutes for Mario Andretti to make himself an ace. To be precise he took 3 minutes 46.63 seconds, pelting his Dean Van Lines Special round Indianapolis to steal pole position and set new four-lap and one-lap qualifying speed records, first time out on the Speedway.

Mario Andretti poses in his Dean Van Lines Brawner-Hawk after qualifying fourth for his first Indianapolis 500 in 1965. He would finish in third and win rookie of the year honors.

That was nine years ago, in 1965, and until then Mario had been just another successful young kid from the dirt tracks, full of apparent potential in his first few USAC Championship races, but yet to deliver the goods. As he pulled his bulbous white Ford-powered car into the Indy pit lane the crowd roared themselves hoarse at his performance. But the wiry 25-year-old Italian immigrant was already looking over his shoulder. Jimmy Clark followed him out onto the Speedway, and he turned in four consecutive laps over 160 mph to steal Andretti’s pole position and his records. At the end of the day, A. J. Foyt had taken top qualifying honours, and Mario was fourth quickest, bumped back to the inside of the second row by Dan Gurney. In the race, his first Indy 500, the tough little man from Nazareth, Pa, then drove like a veteran, despite an intermittent fuel system fault afflicting his car. He lay with the leaders from the start, hounding Rufus Parnelli Jones all the way until the race drew towards its dramatic finish.

Clark rushed home to win for Lotus and Ford, nearly two minutes ahead of Jones’ year-old Lotus which was in deep trouble. It was running low on fuel, and with Andretti just 20-seconds astern, Parnell dared not stop to top-up. On the last lap, Jones zig-zagged his faltering car across the line, just managing to wash the last remaining dregs of fuel into the pick-up pipes, to hold off Andretti by just six seconds.

So the mercurial Rookie was third in his Indianapolis debut, winning a well-deserved Stark & Wetzel Rookie of the Year award, and also being voted Driver of the Year by the Hoosier Auto Racing Fans. They knew what they were talking about. He ended the season by winning the USAC National Championship, and he repeated this feat the following year.

Since then Mario Andretti has become Internationally-acknowledged as one of the most versatile and capable race drivers of all time. He has won on dirt and paved ovals; he has won stock car races on the high-banked super-speedways of the American deep south; he has won on road circuits in USAC Championship cars, long-distance sports car classics, in Formula 5000 and in Formula 1.

In 1969, he won the prestigious Indy 500, and in 1971 he won the South African Grand Prix. He is back in Formula 1, driving for the prime target in that now far-off Indianapolis 500 —for Parnelli Jones. His brand-new Maurice Phillippe-designed Vel’s Parnelli VPJ4 made its debut in ‘Super-Wop’s’ hands in the Canadian GP, and he perched it briefly on pole position for the United States GP at the Glen. Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones now have their team poised to tackle a full World Championship season next year, and after their spoiled Watkins Glen performance, they obviously mean business.

I found Andretti in the Kendall Tech Centre at the Glen after the Grand Prix’s first practice sessions had ended. He had set fastest time. The car was on pole overnight, and there was no mistaking the heart-warming rosy glow around the Vel’s Parnelli work bay.

The Tech Centre at the Glen is a great gloomy barn of a place, fenced off into a series of bays with a spectator-packed aisle down the centre. They pay a dollar a time to pack into the place for a close-up look at the great cars and great names of the day. The place is reminiscent of any English country-town’s covered cattle market, but here the all-pervasive pong is one of synthetic rubber, oil and cleaning fluid, instead of you know what.

Mario is a deceptive character, small in stature, broad-shouldered and powerfully built. He’s a big man in attainment, and he wears competitive nature like a badge. It’s as unmistakable as the Ferrari escutcheon which he still wears proudly on his Firestone jacket.

Motor racing was just starting its final pre-war season, confined to Italian territory, when Mario and Aldo Andretti were born as twins on February 28, 1940. Father was a farmer, and the family had seven farms in lstria, around Trieste where the Adriatic bites the division between Italy and Yugoslavia. At the end of the war, the Andrettis’ land was swallowed by a political settlement with Yugoslavia. The family wanted to stay Italian as the border was adjusted, so they abandoned their heritage to the new communist state and joined thousands of refugees moving westward.

Andretti is matter-of-fact about what must have been at first a confusing and later a bitter experience for a young kid. “We left in 1948, and lived in a refugee camp at Lucca—it’s near Pisa—for the next seven years. Yeah, it was tough. There were twen’y-seven families all living in one big room, about the size of this…”, he said, waving his hand at the Tech Centre’s walls.

“It was in Lucca that Aldo and I started around the local garage. The guy who ran it had ambitions for his son in racing, bought a Stanguellini and kind of pushed him into it. We were only around t’irteen or fifteen, and we used to help around and just soaked up the racing atmosphere. I remember there was one really great day, we went to Modena to pick up a ’53 Ferrari for the Mille Miglia, that was a great thing… “.

“We had an uncle, he was a priest, called Ghersa Quirino, and I guess he sympathised with our ent’usiasm. He bought us a 175cc MV motorcycle, without our parents knowing, and we raised hell with that around Lucca— all these little tight streets and alleys you know, it was the ideal training ground. We really loved motorcycle road racing…” (expansive gesture with the hands) “…any kind of road racing, and then we had great aspirations to get properly involved sometime.”

The family had relatives already living in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, and they acted as sponsors to help Mario’s folks emigrate there in the late ’fifties. By that time Mario and Aldo had driven their first motor races in an 85-horsepower Stanguellini-Fiat Formula Junior car, and they came to America hoping that at least one thing would not have changed much in their new life.

They were in luck. Three days after arriving in Nazareth they heard the rumble of modified stock cars racing on a nearby track: “We got over there quick as we could. We looked at the people driving and at the cars they drove and thought ‘hey, this looks easy’, and that was that….”.

The twins had another uncle, Louis Messenlehner (“…he was German, you know, on my mother’s side…”) who helped them to learn the language and, clandestinely so their parents would not suspect, to put together a modified stock car of their own.

“It was an old ’48 Hudson. Marshall Teague had been king in those cars until he was killed the year before we got started, but his folks and mechanics gave us all their know-how on spring-rates and shockers; it was pretty much unknown sophisticated stuff at that time.

“You had to be 21 before you could race in America, and we were only 17, but Les Young who was a newspaper editor on the ‘Nazareth Key’ helped camouflage our date of birth and we got in there. Aldo won the first race from starting at the back. We won our first three events, you know, we were quite successful all through our stock car days…”.

They had some low notes, as when in their first season (1958) Aldo got the Hudson out of shape and crashed heavily during a race at Hatfield, Pa. He suffered a concussion, and Mario had a hard time convincing Papa that Aldo had accidentally fallen off the top of a truck while watching the racing.

Unfortunately, Aldo was never again to be quite such an accomplished natural driver as his brother, and after trying hard in midget and sprint cars, he sustained severe head injuries through crashing a sprinter in 1969 and hasn’t raced since. Today he lives in Indianapolis, runs a couple of Andretti Firestone tyres stores, and accompanies his brother to most of his races.

In 1958, ’59 and ’60 Mario won over 20 modified stock car events, and in 1961 moved into the single-seater scene on the URC Sprint Car circuit. He was old enough to race legally but had some problems making the transition. “I just didn’t know which way that car was goin’ to go”. He ran with URC until the middle of 1962, when he began driving midgets in ARDC.

It was a rough and tumble schoolroom, of a type simply non-existent in Europe, which provided a staggering amount of experience: “I did 107 races in 1963, you know…

“In Midgets, you can regularly do 80 races on up each year. Sometimes we’d do t’ree races a week, and on Labour Day ’63 I won three races in two meetin’s ! Today just physically you can’t do that, but those Midgets really were the most constructive racing I’ve ever done. I tell you, you never run closer than in Midgets. You’d have 45-50 cars to qualify for only 18 places in the Final, and winning in Midgets can give tremendous satisfaction. I really felt I was accomplishin’ somethin’.”

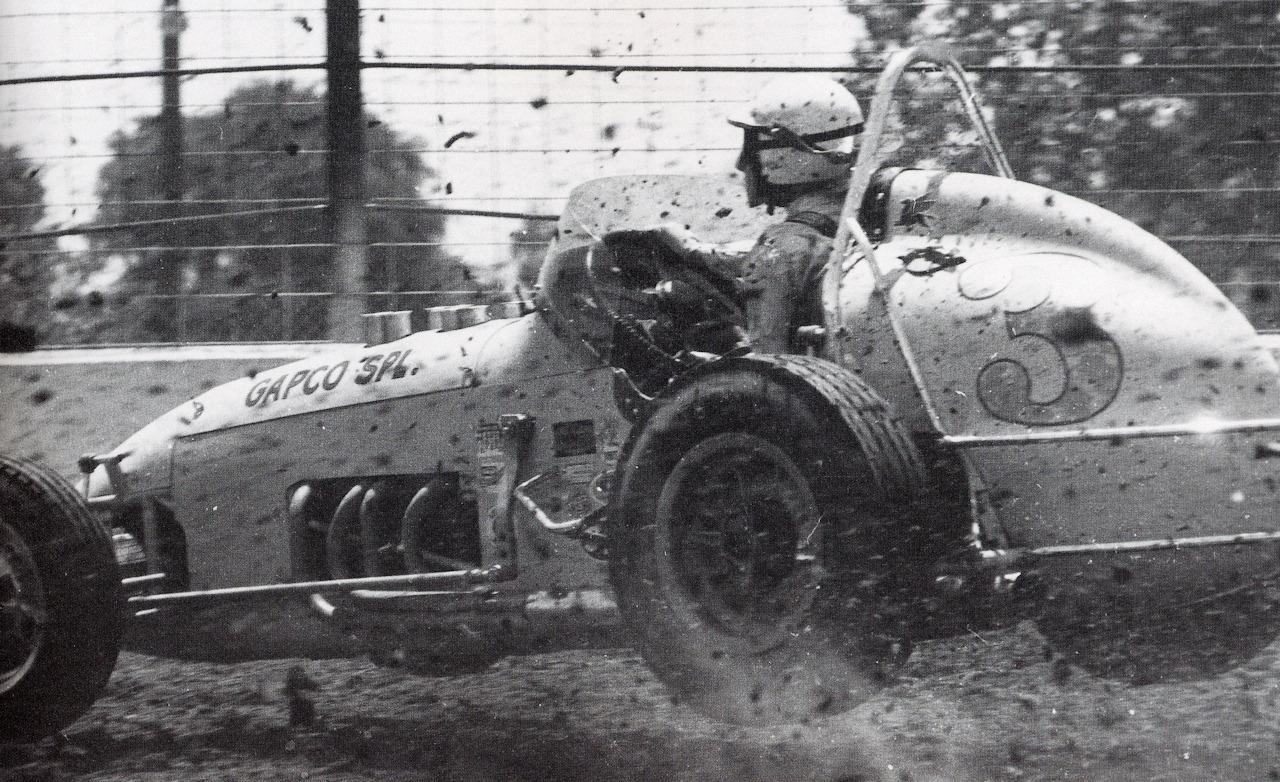

Andretti continued to race Sprint cars on dirt even as his international racing career took off, as pictured here at Terre Haute in 1965.

He drove an Offy-powered Midget for Bill and Ed Mataka that season, and early in 1964, he joined the United States Auto Club to get into Championship racing, to tackle the big-time. “That had been my goal since I started in sprints, you know. When you’re just starting you gotta set your aims high; unreasonably high at the time, and you just gotta get out and get after them. You tell yourself to do it…”, a shake of the head, “Shit, you just tell yourself these things, you know….”

Mario hangs in out in the dirt at Sacramento in 1966.

Mario’s first Championship race was at Trenton, NJ, in March ’64, and it wasn’t too happy a debut. “I was like a fish out of water. I mean I spun three times. I tell you, I just felt incapable! Those paved tracks were hard to drive at first. I was used to hanging my Sprint car out and tossing it around. In comparison those roadsters were a son of a bitch, you had to drive ’em like t’readin’ a needle…”

The story goes that Mario visited Indy that year; just a 24-year-old dirt track driver soaking up the Speedway’s carefully manufactured mystique for the first time. But he wasn’t overawed by the place. He was wandering around Gasoline Alley looking for a drive. He looked up Al Dean’s veteran crew chief Clint Brawner, who had just lost his driver when Chuck Hulse was seriously injured in a sprint crash earlier that month. Rufus Grey, who owned the sprint car Andretti was driving at the time, introduced his young protégé and tried to talk him into Brawner’s Dean Van Lines roadster. When he mentioned that Mario raced sprint cars, Brawner’s sun-sensitive neck apparently reddened, he bawled “Goddammit, sprint’s a dirty word in this garage”, and tossed the hopeful applicants out of the door!

But Brawner had heard of Andretti’s prowess from other sources, and a month later he watched Mario drive at Terre Haute and offered him the Dean drive, mere or less as a trial until Hulse recovered. The compact little Italian jumped at the chance; “In major league racing, I figured there were only a few outfits worth driving for, that were going to produce a winner. I considered Dean one of these, so I t’ought maybe I’m gettin’ into somethin’ good.”

He drove the Dean Van Lines Special in the last eight Championship races of the ’64 season, was third in the Milwaukee ‘200’ and notched sufficient points for 11th in the Championship standings. He drove in 20 sprint races, was third in the standings and highlighted with victory in the Joe James-Pat O’Connor Memorial 100-lapper at Salem.

— Continued in Part Two

Here is many Americans’ favorite Grand Prix driver Dan Gurney taking the Nouveau Monde hairpin at the bottom of the Rouen-Les Essarts public road circuit during the French Grand Prix on July 8, 1962, in the Porsche 801 flat-8 Grand Prix car. The Porsche was a rather new car and had recently undergone substantial suspension and bodywork revisions based on extensive testing at the Nürburgring. Gurney was not forecast to be particularly competitive – in fact, he was back on the third row of the grid – but with some attrition, he surprised everyone by taking an unexpected victory.

The week before the French race all the British teams, Lotus, Cooper, Lola and BRM, had been at the super-fast Reims circuit for the non-Championship Reims Grand Prix, the new name for the prewar Grand Prix de la Marne, joined by two privately entered Porsche 718s. Ferrari, although entered, as here at Rouen, did not show up due to metalworkers strikes in Italy.

To whet the attention of the spectators, race day began with two Formula Junior heats and even a bicycle race. But soon things got down to some real F1 racing. At the start, seen here, Graham Hill in his BRM 57 leapt out to small lead ahead of Jim Clark’s Lotus 25, Bruce McLaren’s Cooper T60 and new F1 driver John Surtees with the Lola 4-Climax. Gurney was back in sixth place but stayed in touch with the leaders. His teammate Joakim Bonnier had the second Porsche 801, but was not at Gurney’s level, the American having received the majority of the Porsche mechanics’ attention during practice.

Before long McLaren stopped at the pits, but continued a couple of laps in arrears while Brabham brought his Lotus in to retire with broken suspension. At half distance it was Graham Hill still out in front with Clark’s Lotus in second and now Gurney up to third. Clark set a new lap record, but the decided all was not well with his car and came into the pits which left Hill in the lead by some 30 seconds over Gurney while Surtees’ Lola was third but a lap down. Then, with 12 laps to go, Hill pulled off at Nouveau Monde with injection troubles which gave Gurney the lead which he carefully held to the finish. The tail-enders also found that it pays to keep running as Tony Maggs with his Lotus was second one lap down and Richie Ginther in the second works BRM was third, two laps behind.

Because of Ferrari’s absence, their World Champion Phil Hill was but a spectator at Rouen, busy taking photographs with his Leica.

Photos by Louis Klemantaski ©The Klemantaski Collection – http://www.klemcoll.com