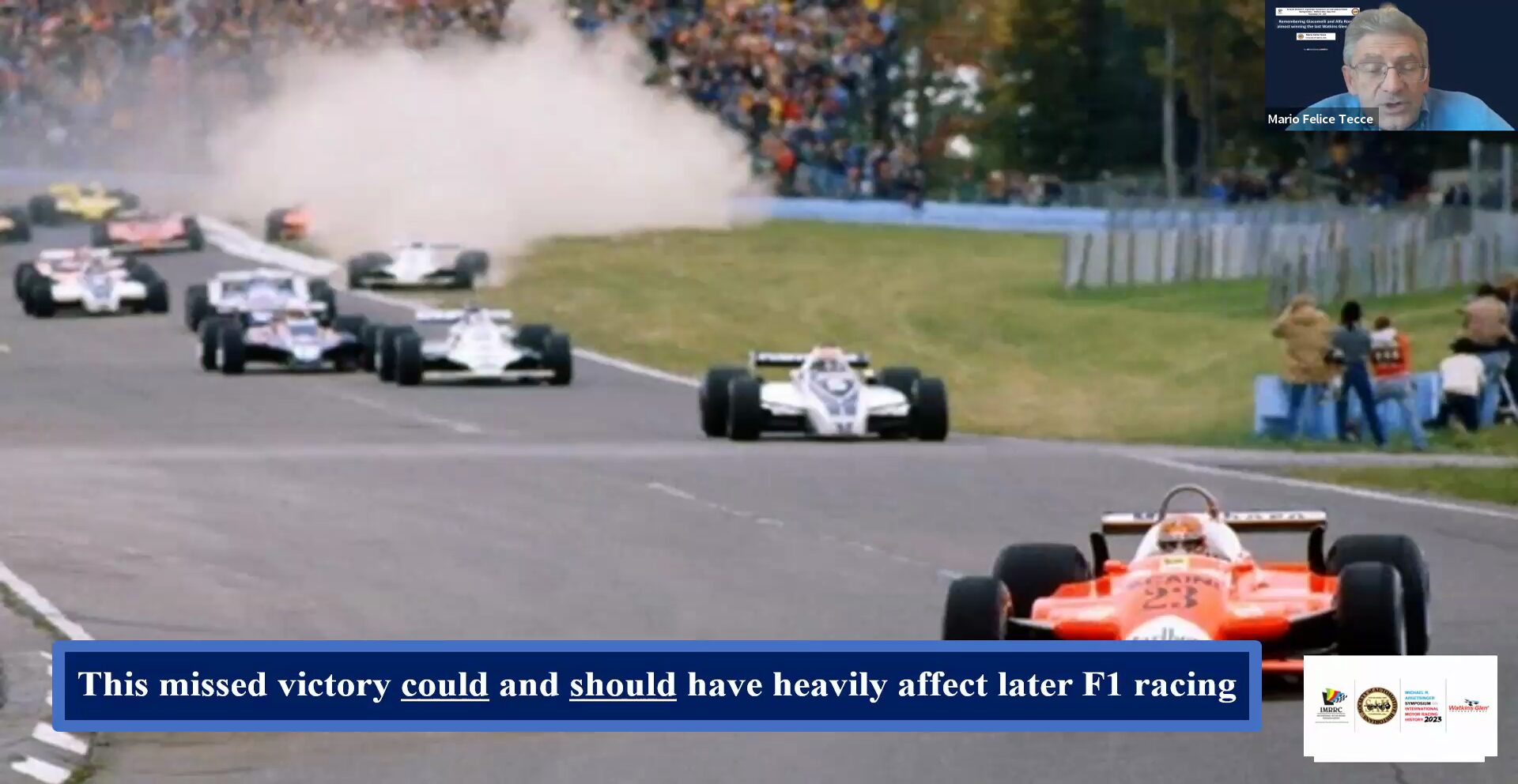

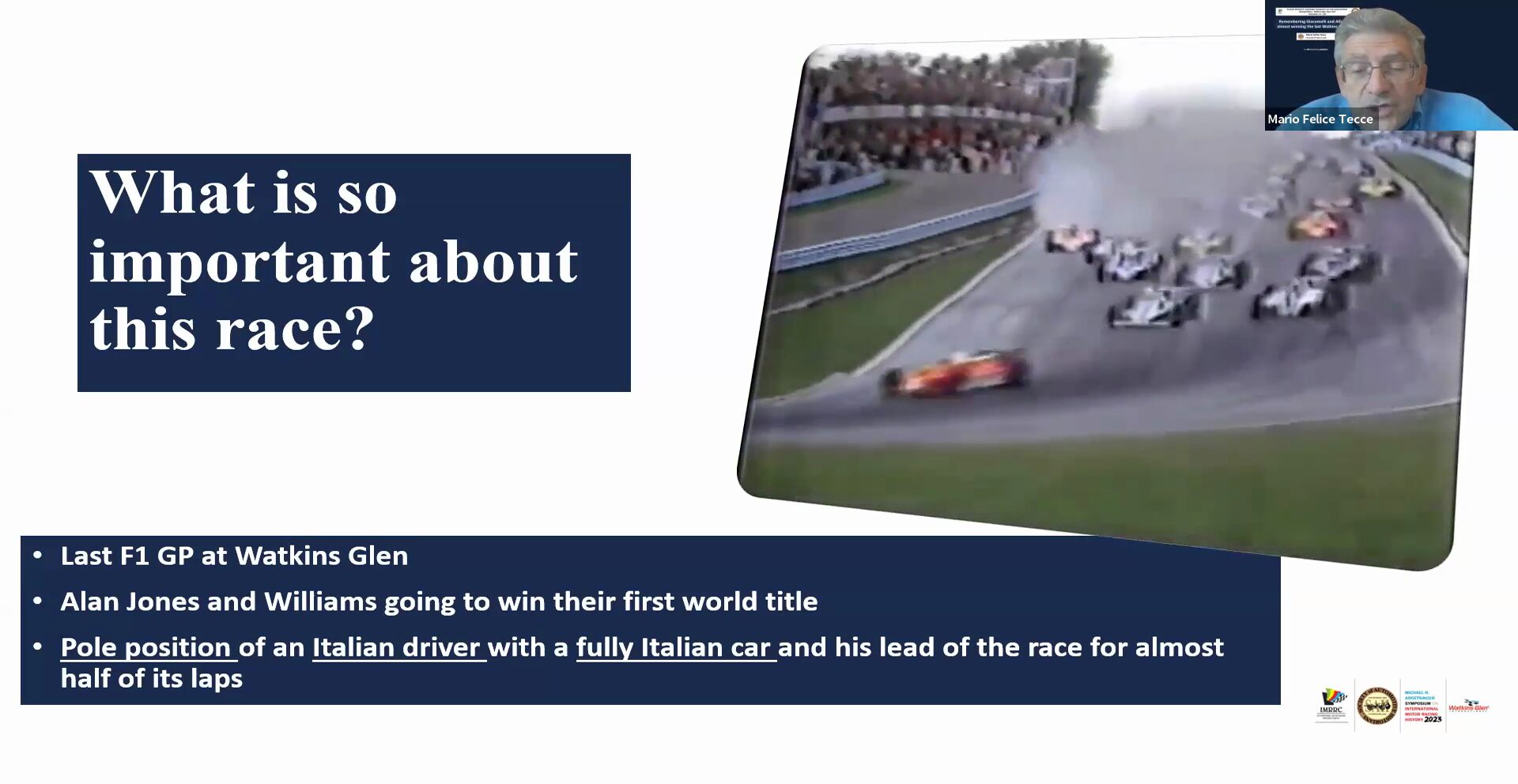

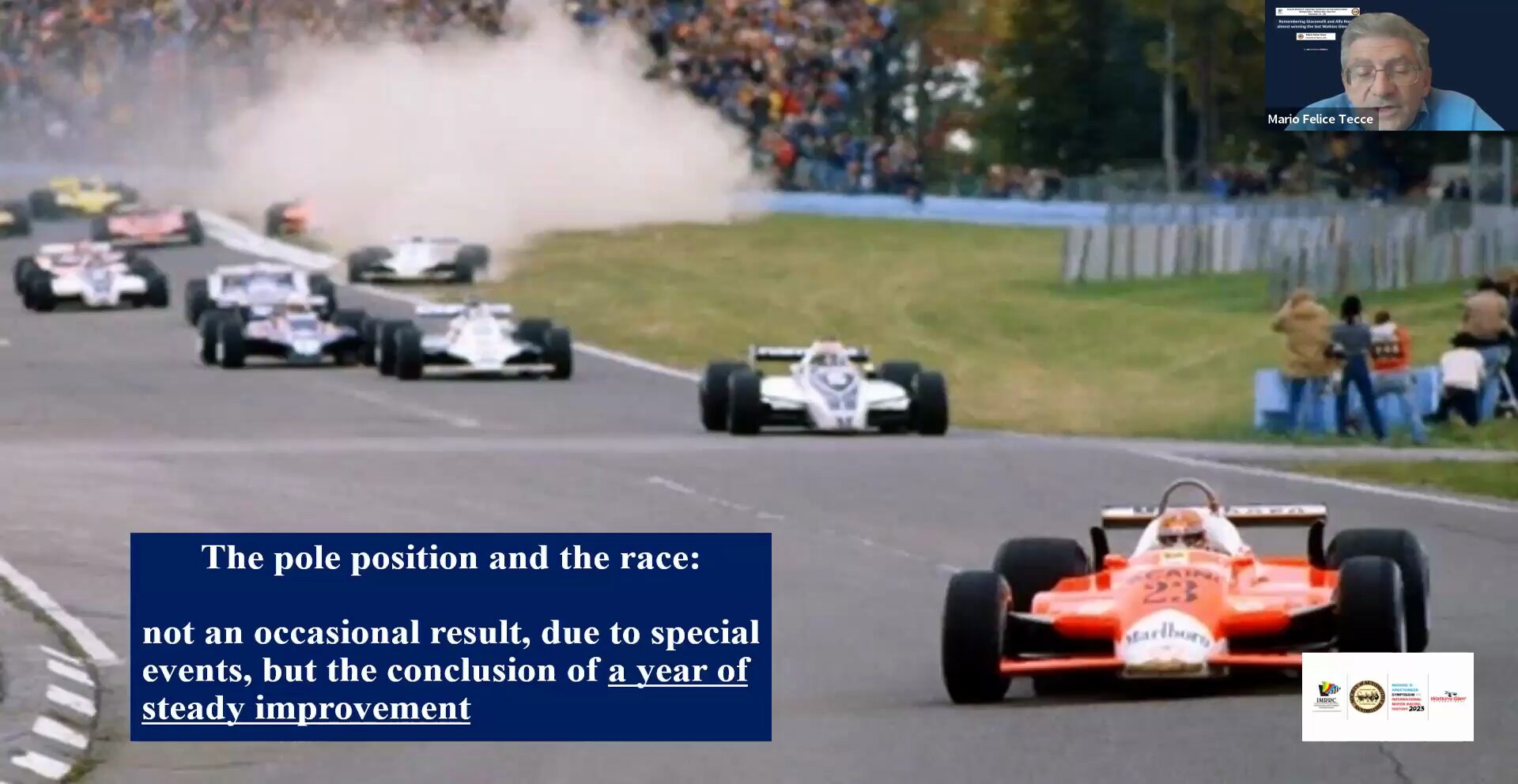

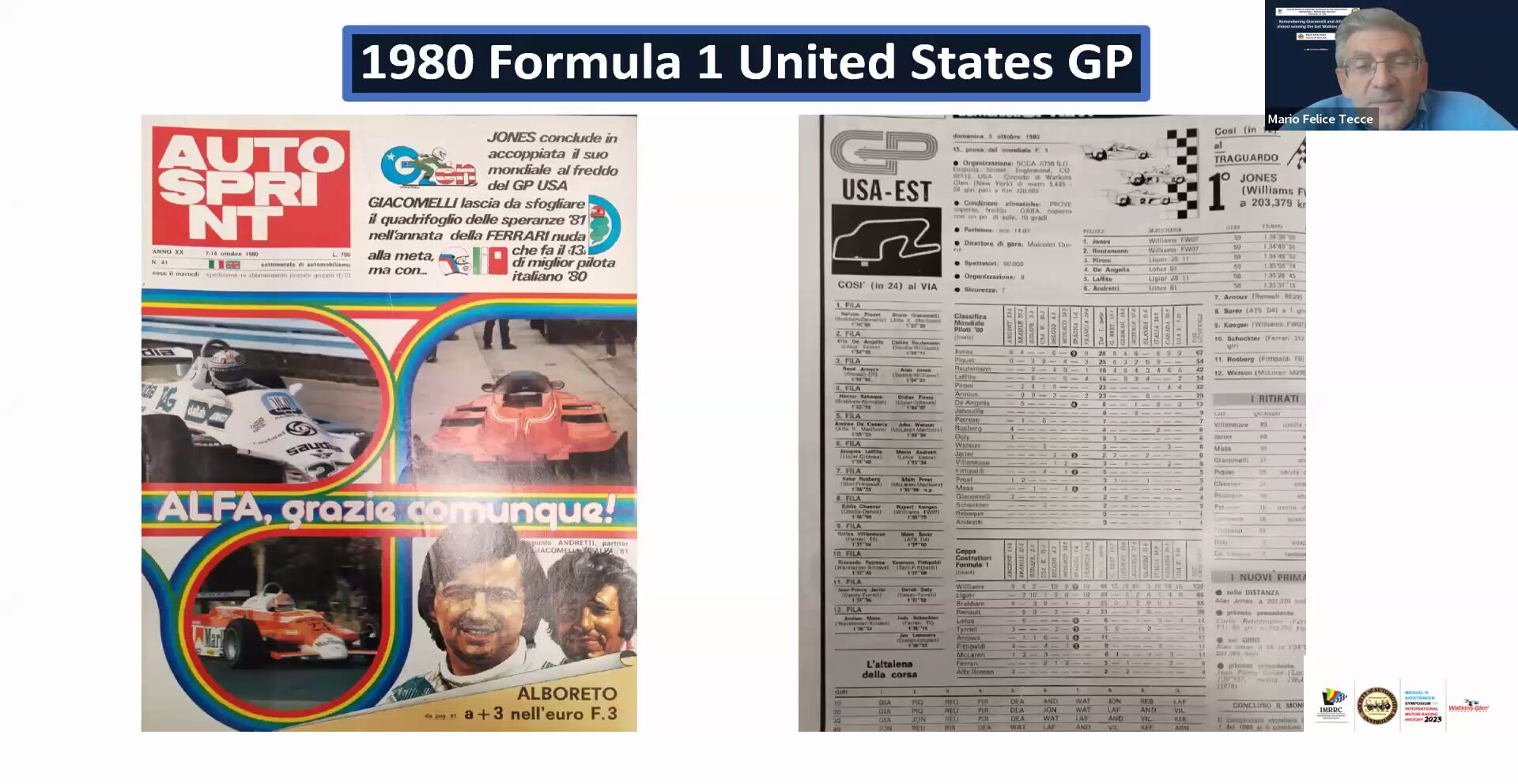

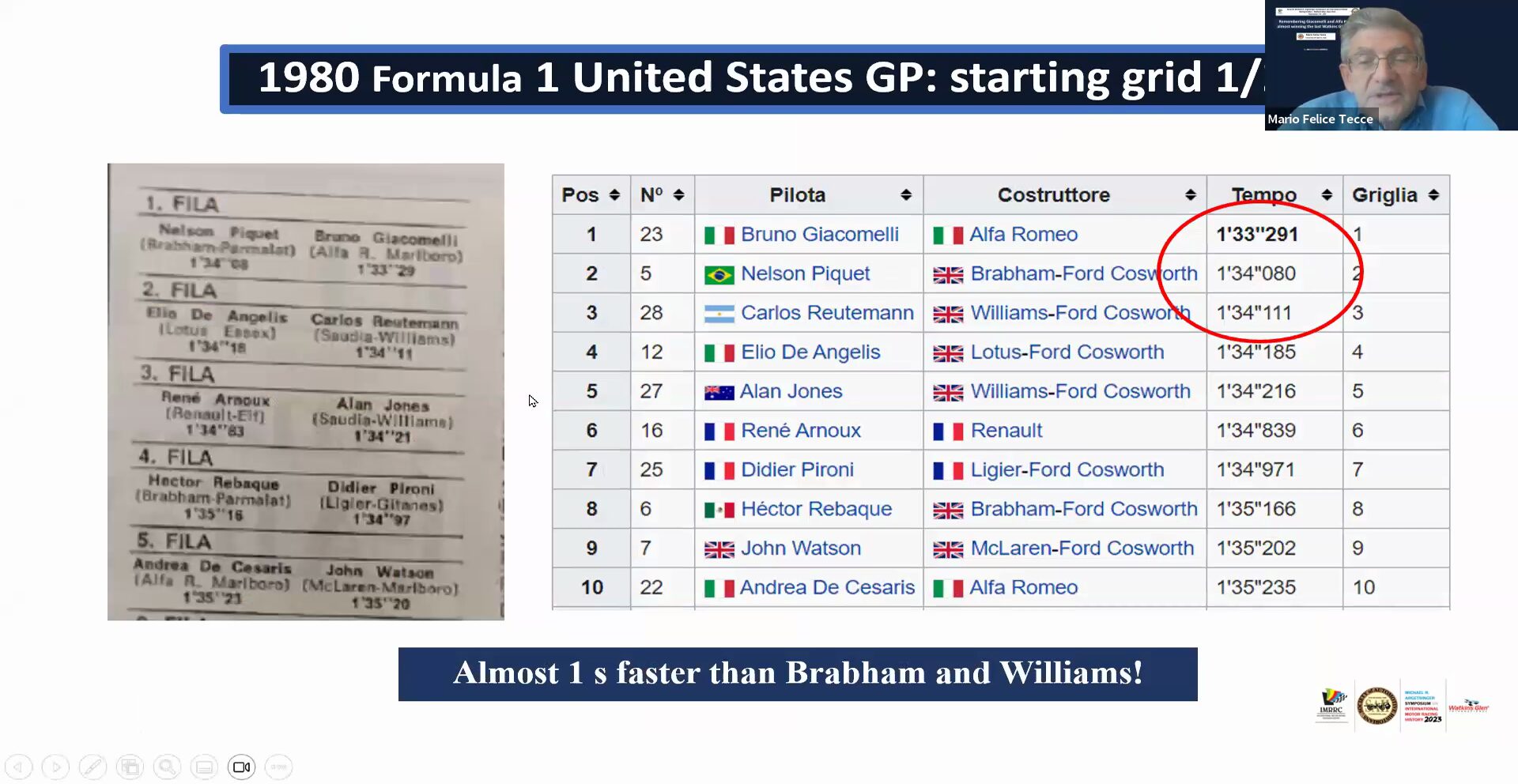

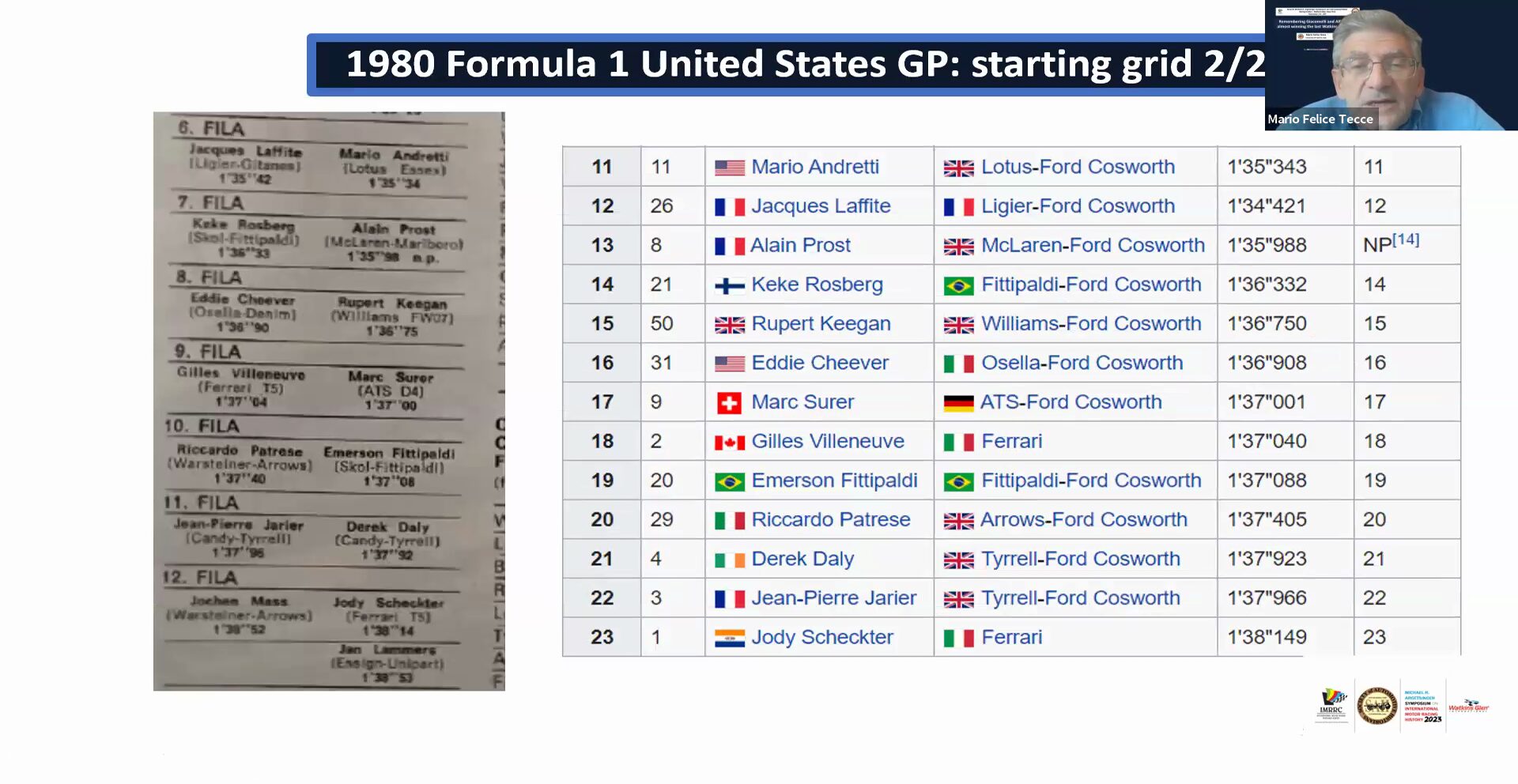

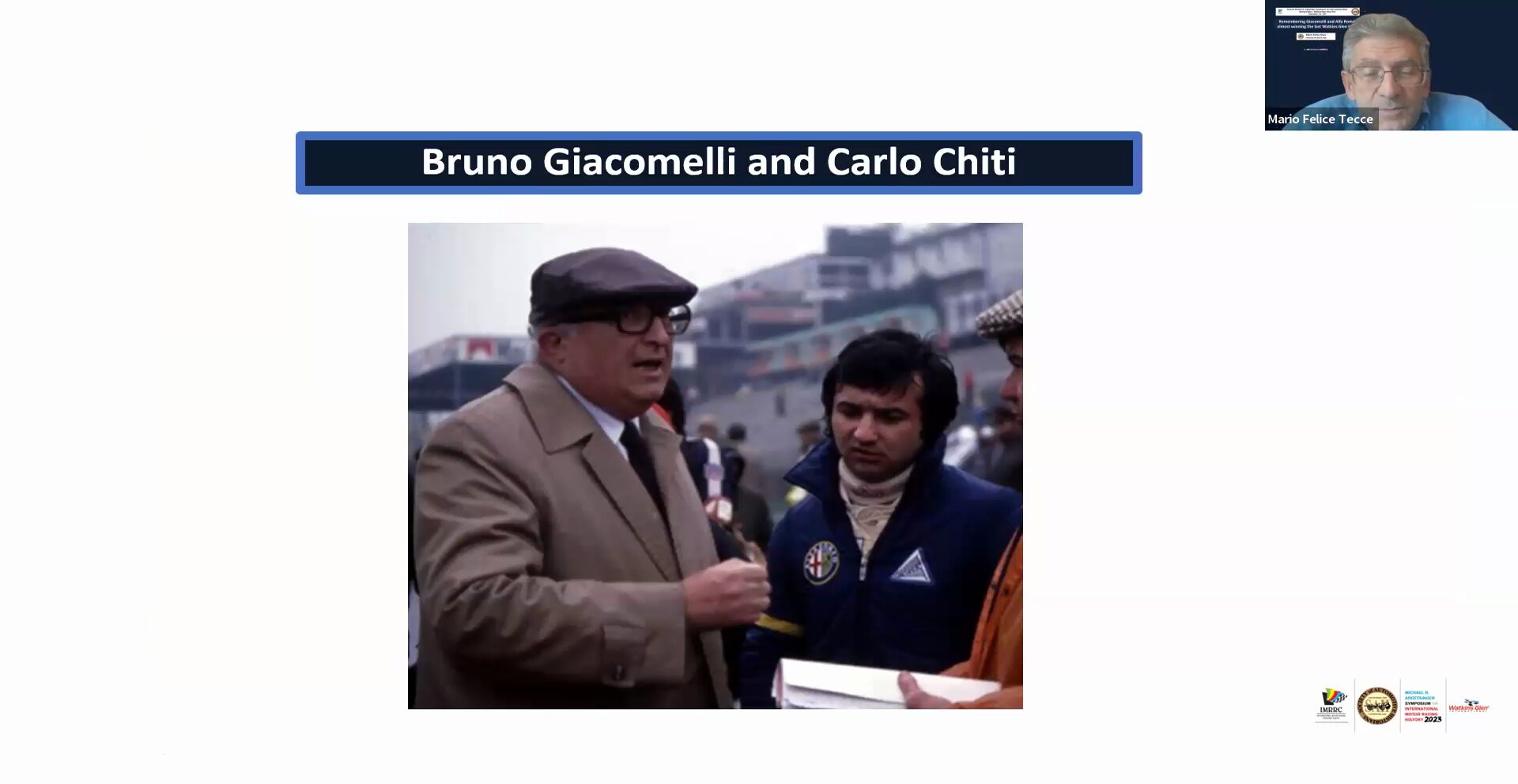

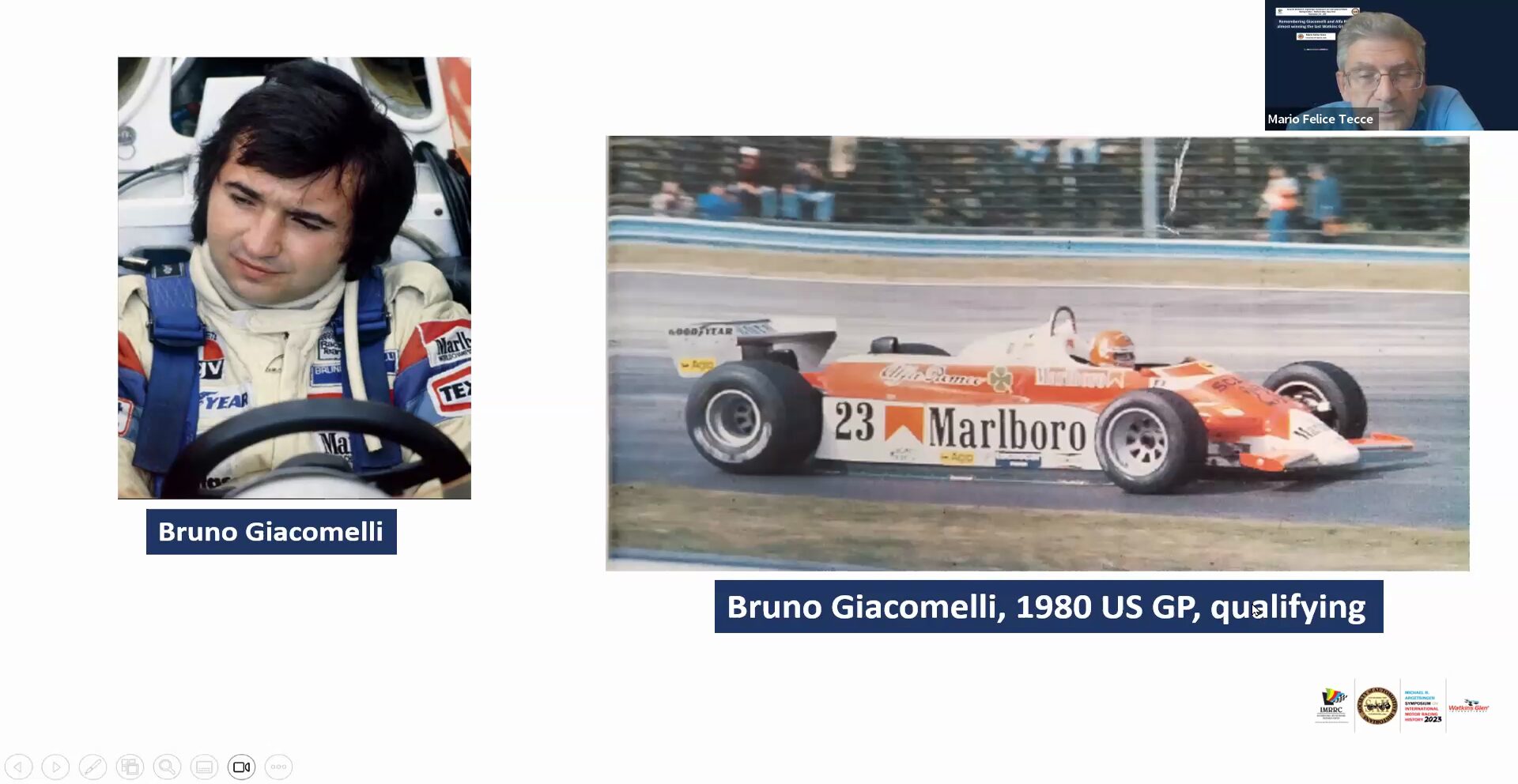

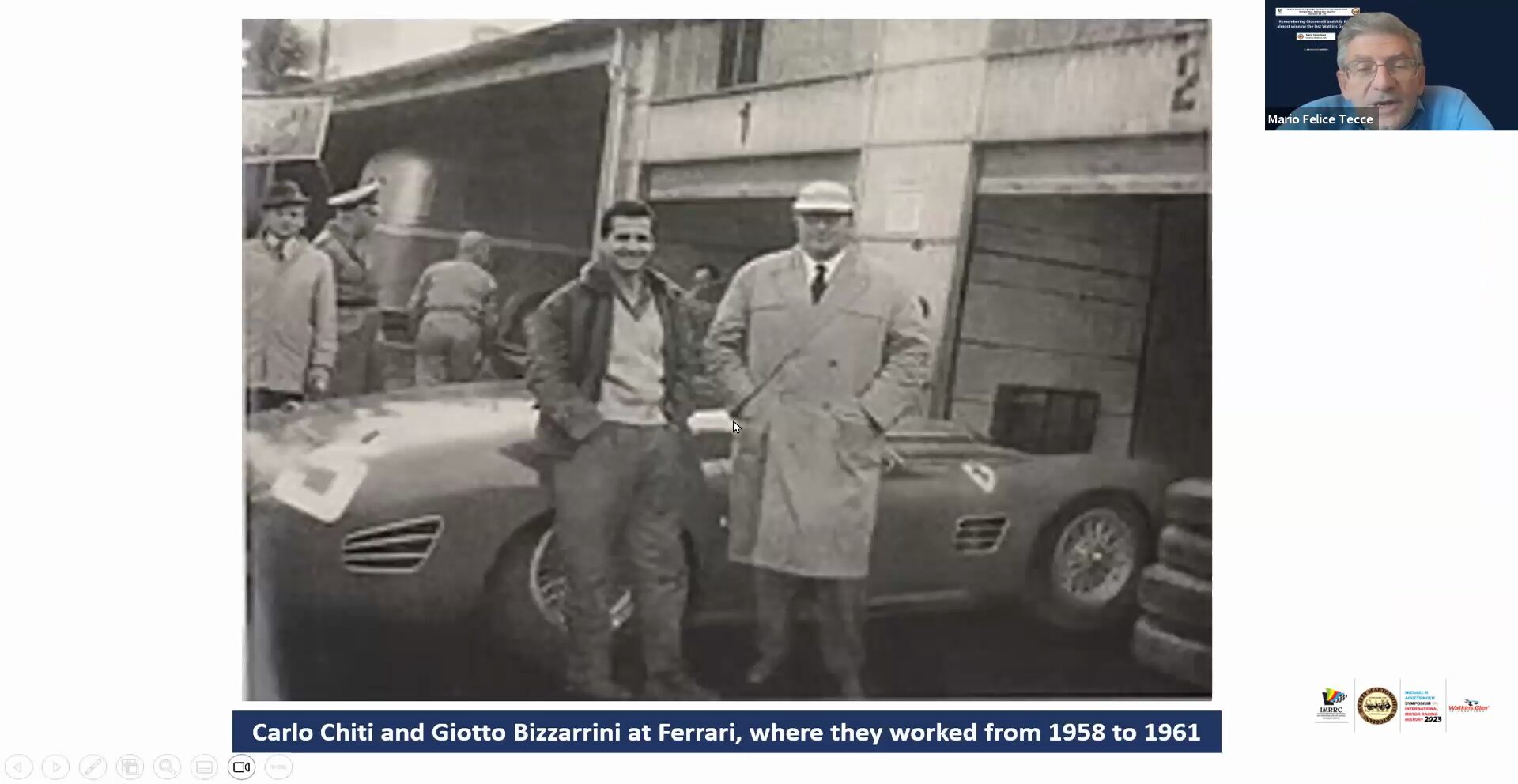

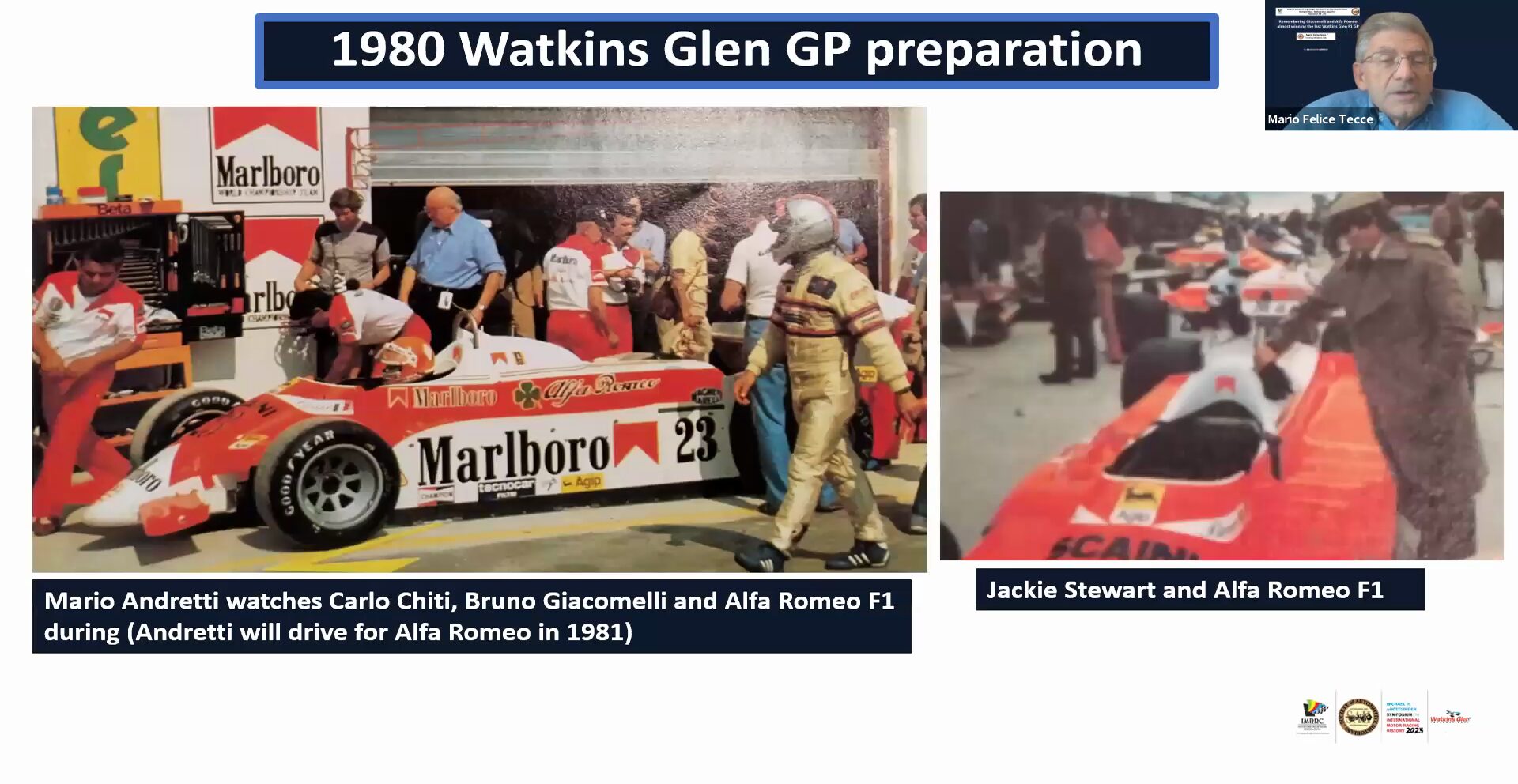

October 5, 1980, was a very important day at Watkins Glen International circuit. Historical research, including about motor racing, cannot be done with hypotheses or with “what ifs” but only with facts. However, it can indeed be conceived that the facts of that day affected many future things. This was going to be the last F1 GP at Watkins Glen. The starting grid had an unexpected pole sitter: the Alfa Romeo of Bruno Giacomelli. Those were the years of Ferrari, winner of 1979 championship, of Lotus, winning in 1978, while the age of Williams was just beginning. Alfa Romeo, although possessing ancient racing victories, was back in racing for less than 2 years.

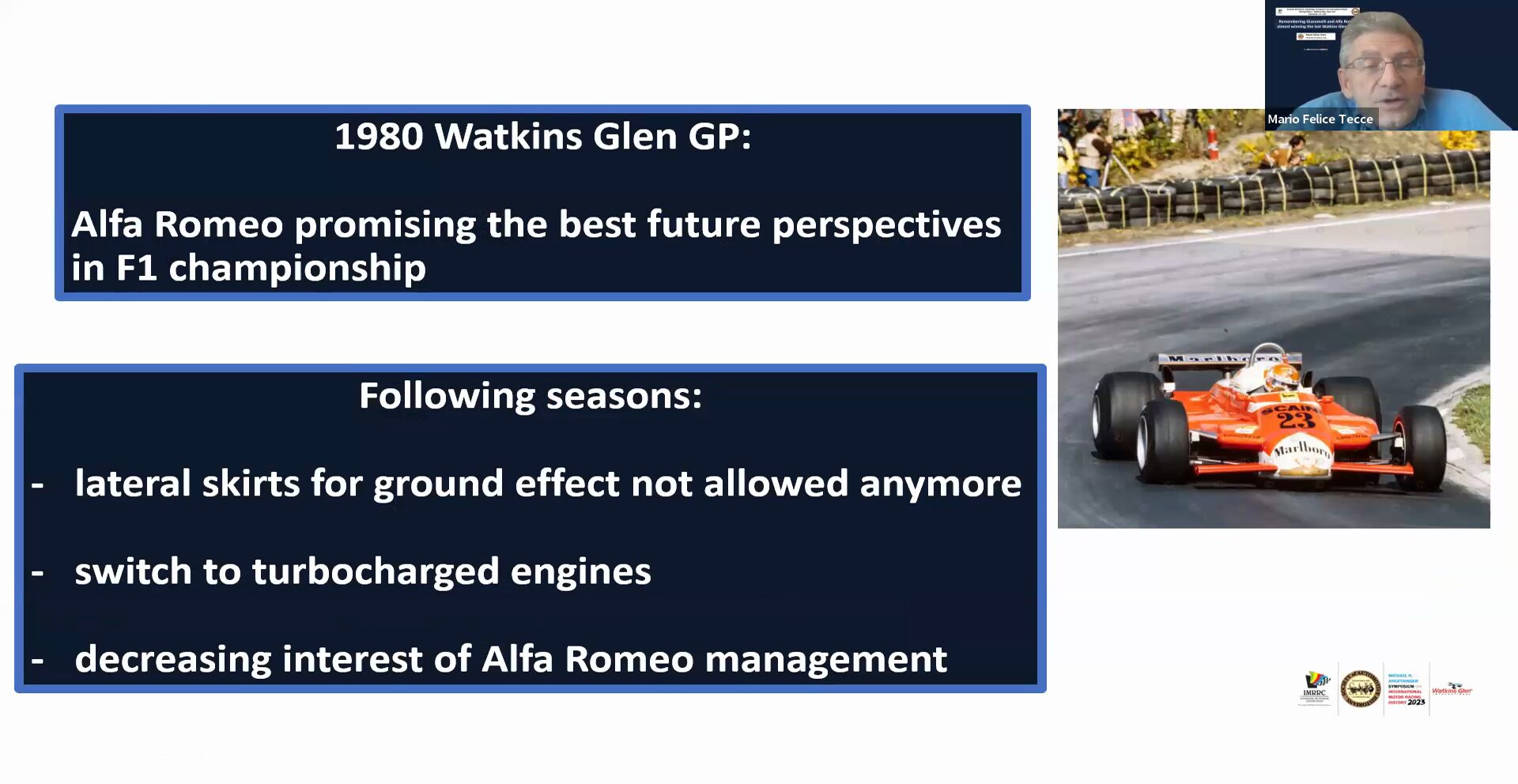

Giacomelli, an Italian driving a fully Italian car, started on the pole maintaining firmly his lead position. He kept the lead and seemed close to an extraordinary win. Suddenly, a minor electrical problem stopped him on the track and the Williams of Jones won the race. One wonders what would have been if Giacomelli had won. Perhaps Alfa Romeo’s racing efforts would not have been discontinued as happened and a second major Italian team would have stayed in Formula 1. Possibly a prestigious F1 win in the US, the major car market in the world, and eventual further successes could have improved the prospects of Alfa Romeo to remain an Italian state property and continue to progress as an independent firm.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Dr. Tecce received his M.D. and PhD. at the University of Naples, Italy, and is currently full profession of biochemistry at University of Salerno. Besides his molecular research about cancer mechanisms, he explored race car driving as a major reference paradigm of pursuing the best and of free will exercise.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

English Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

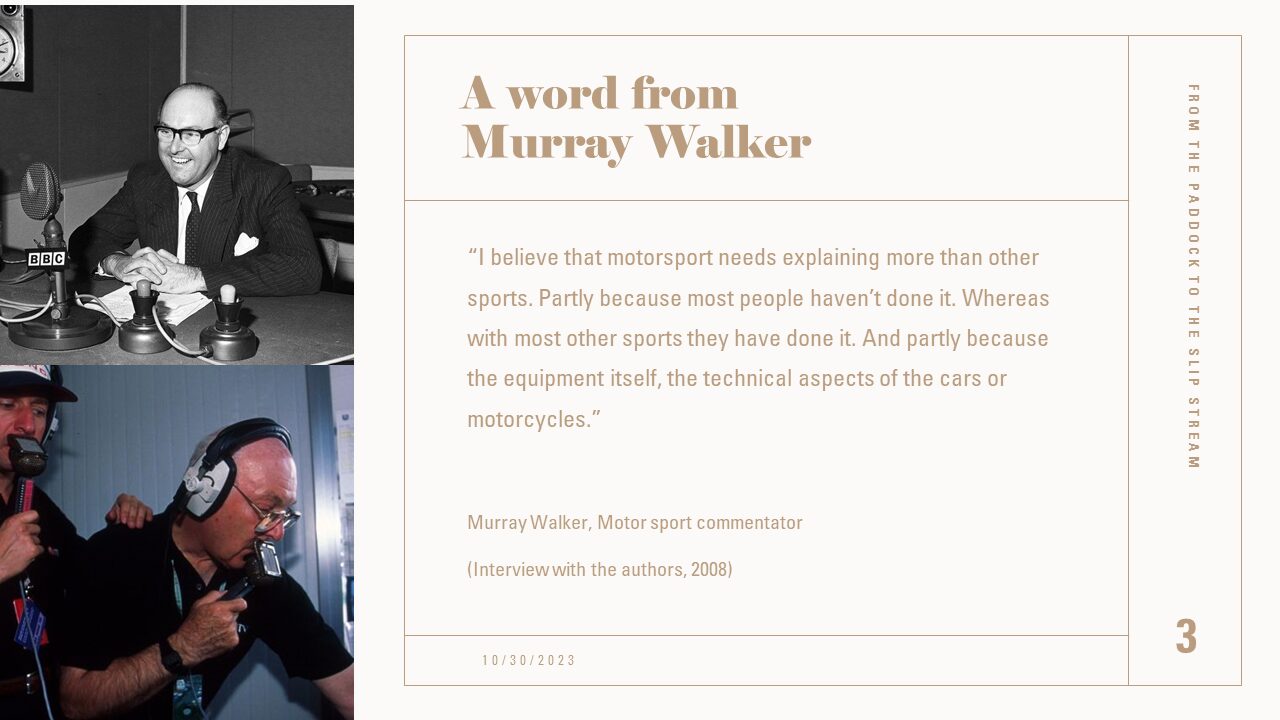

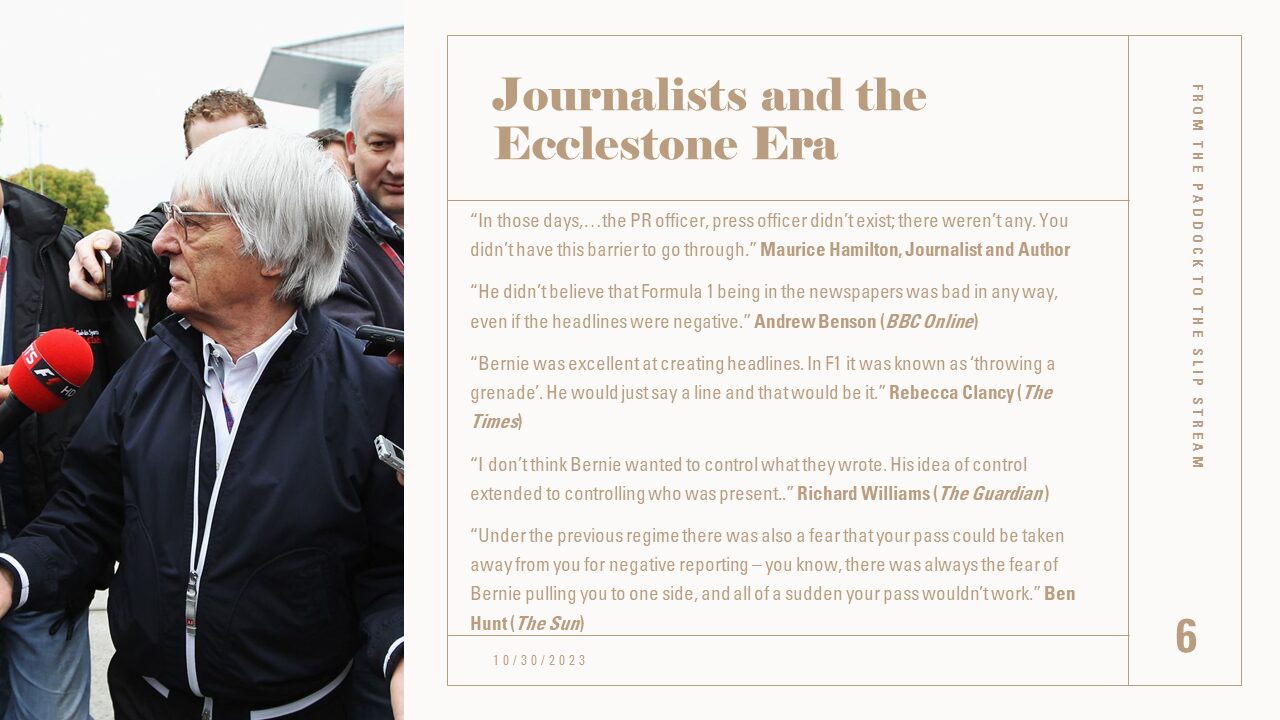

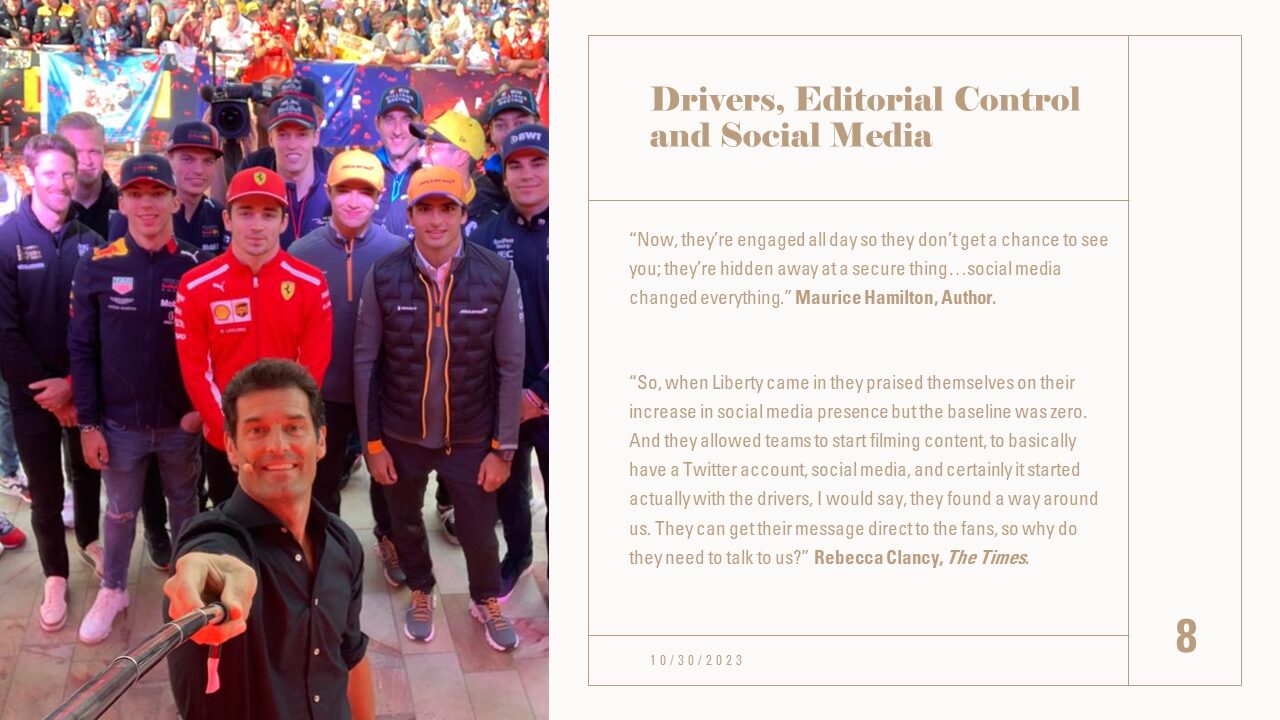

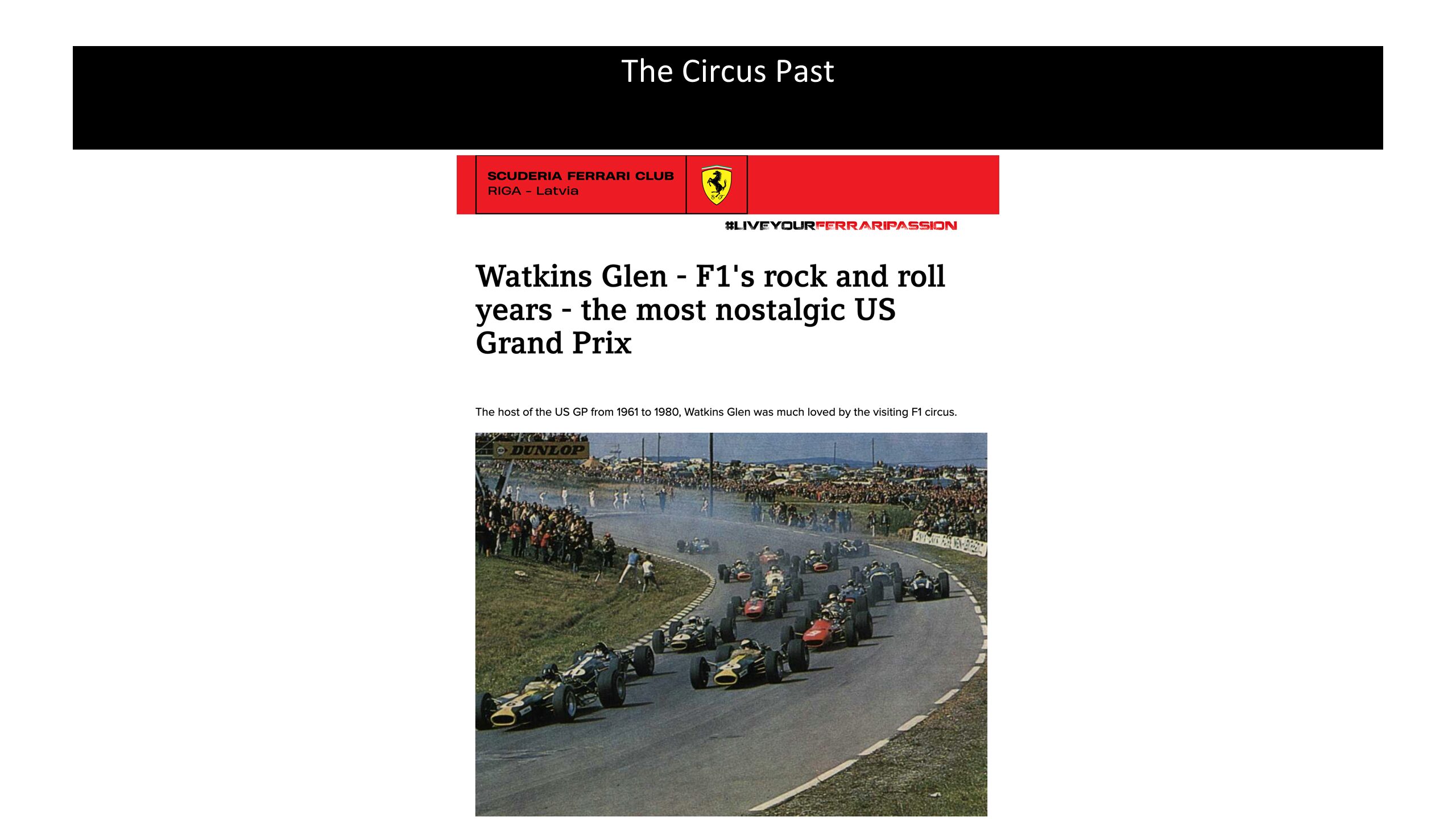

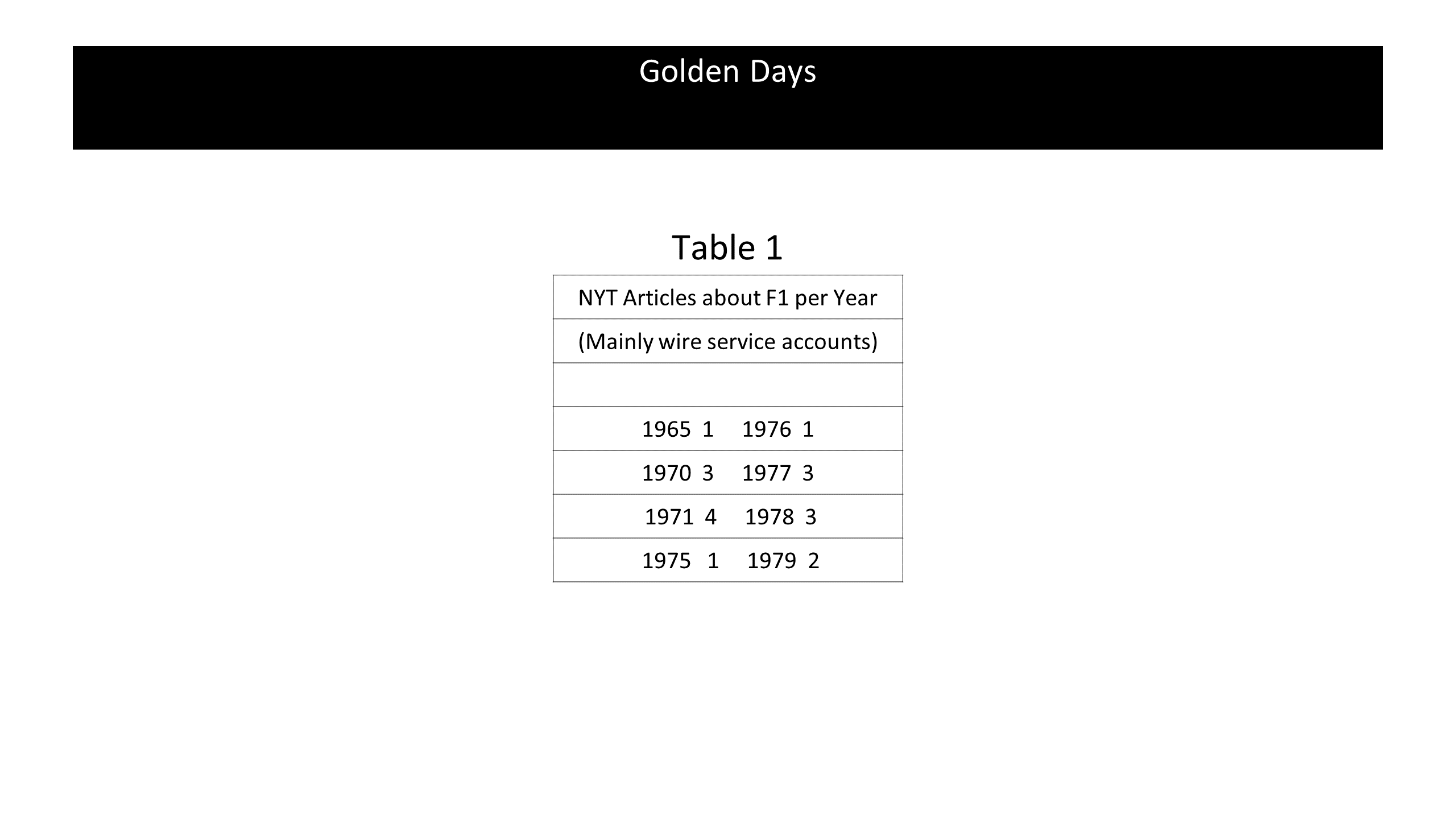

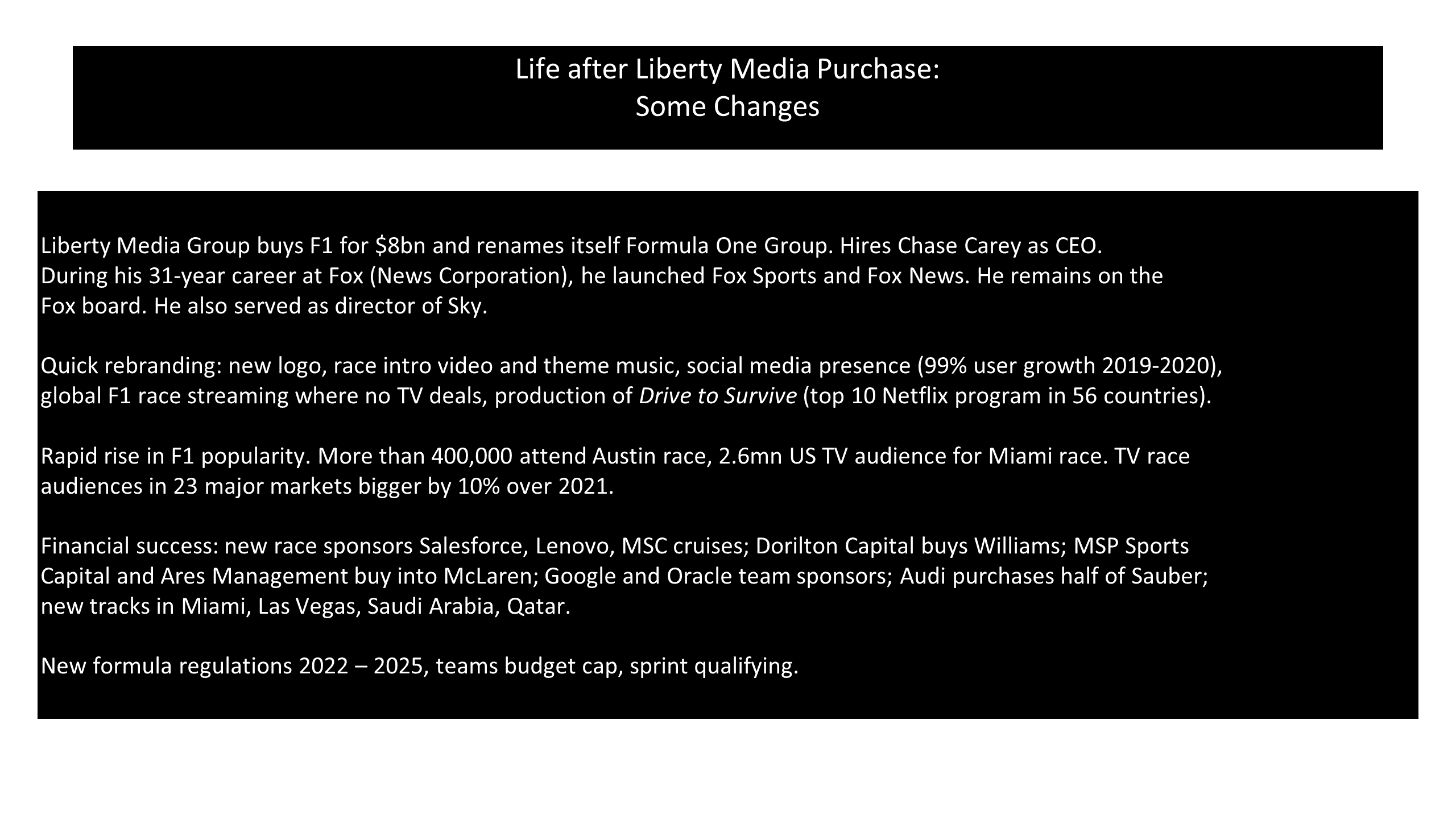

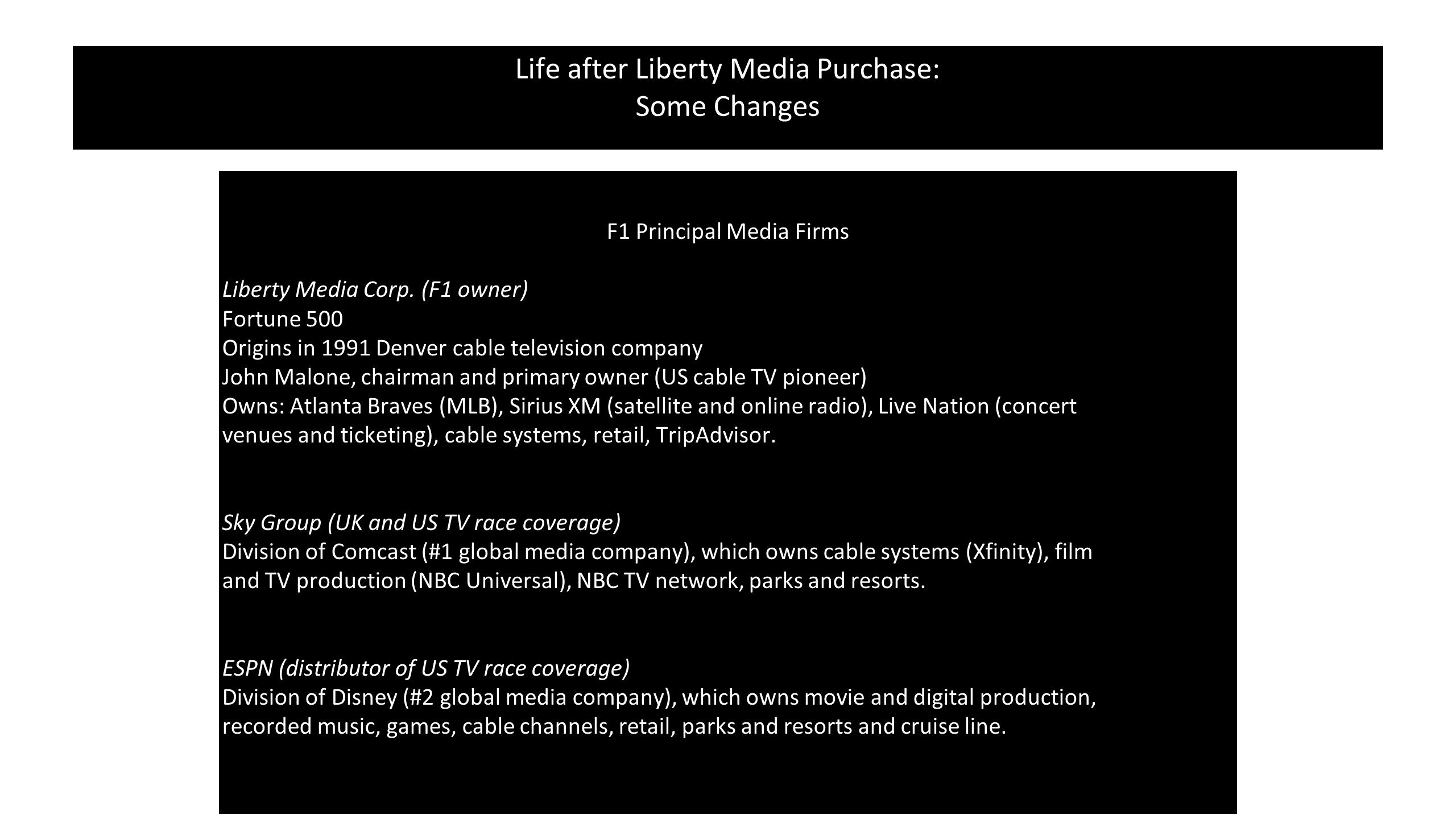

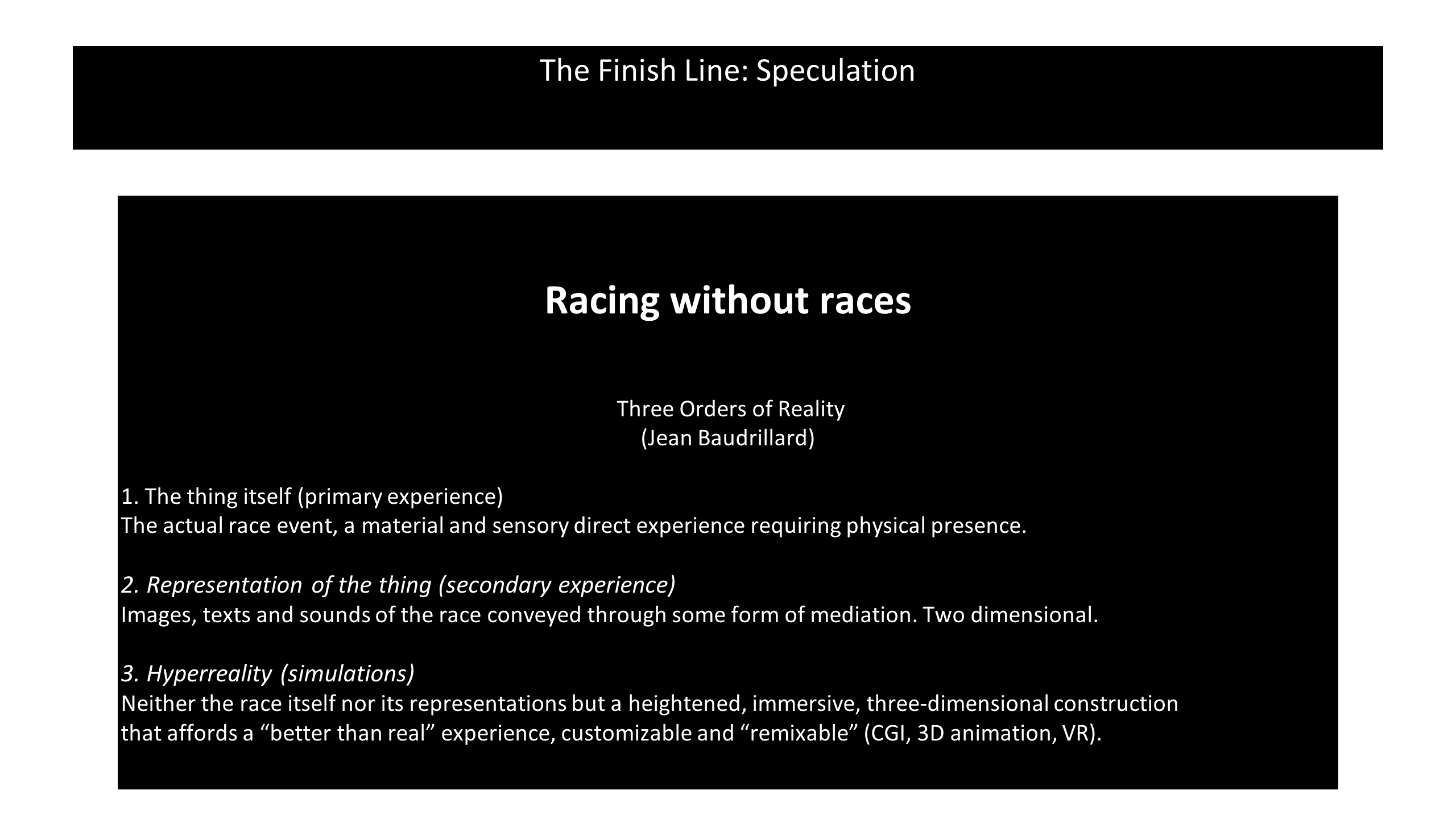

Based on archival and biographical research and interviews with British journalists, broadcasters and communications managers, this presentation provides an analysis of the transformations in media relations in Formula One from 1960s onward. The paper explores the professional careers of leading British journalists and broadcasters of F1 to explore how media relations have changed over time. We conclude with some thoughts on how F1 in the era of Liberty Media, is bringing new opportunities for F1 across different platforms, transforming again the media relations of the sport.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Richard Haynes is professor of Media Sport in the Division of Communications, Media and Culture at the University of Stirling, Scotland. He is author of seven books on sport and communications including the award-winning history BBC Sport in Black and White (Palgrave 2016) and his forthcoming book with Raymond Boyle Streaming the Formula 1 Rivalry: Sport and the Media in the Platform Age to be published by Peter Lang in 2024.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Other episodes you might enjoy

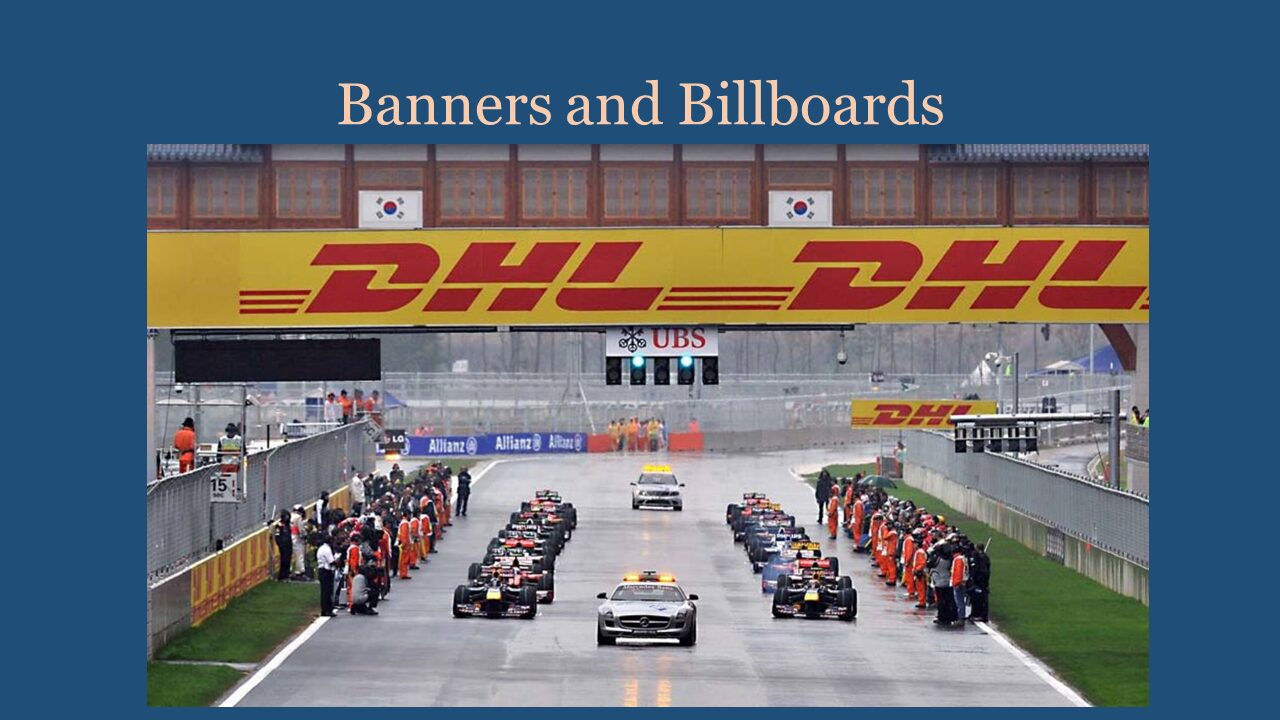

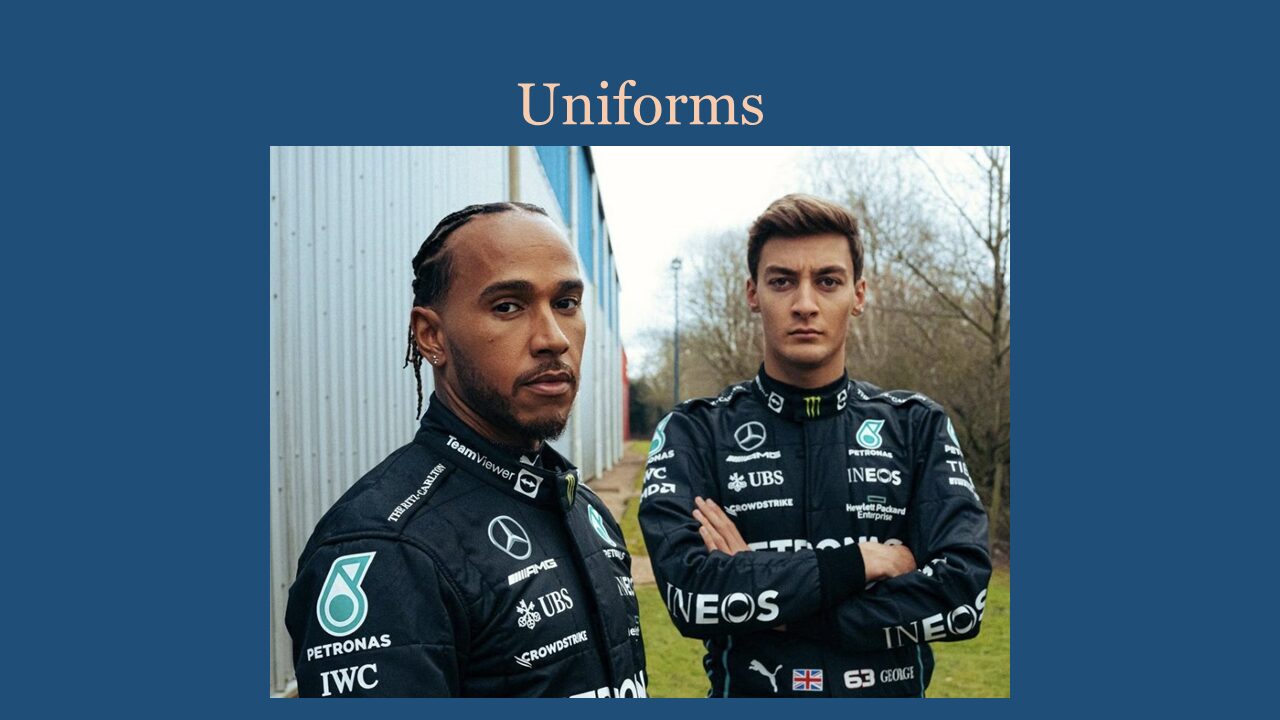

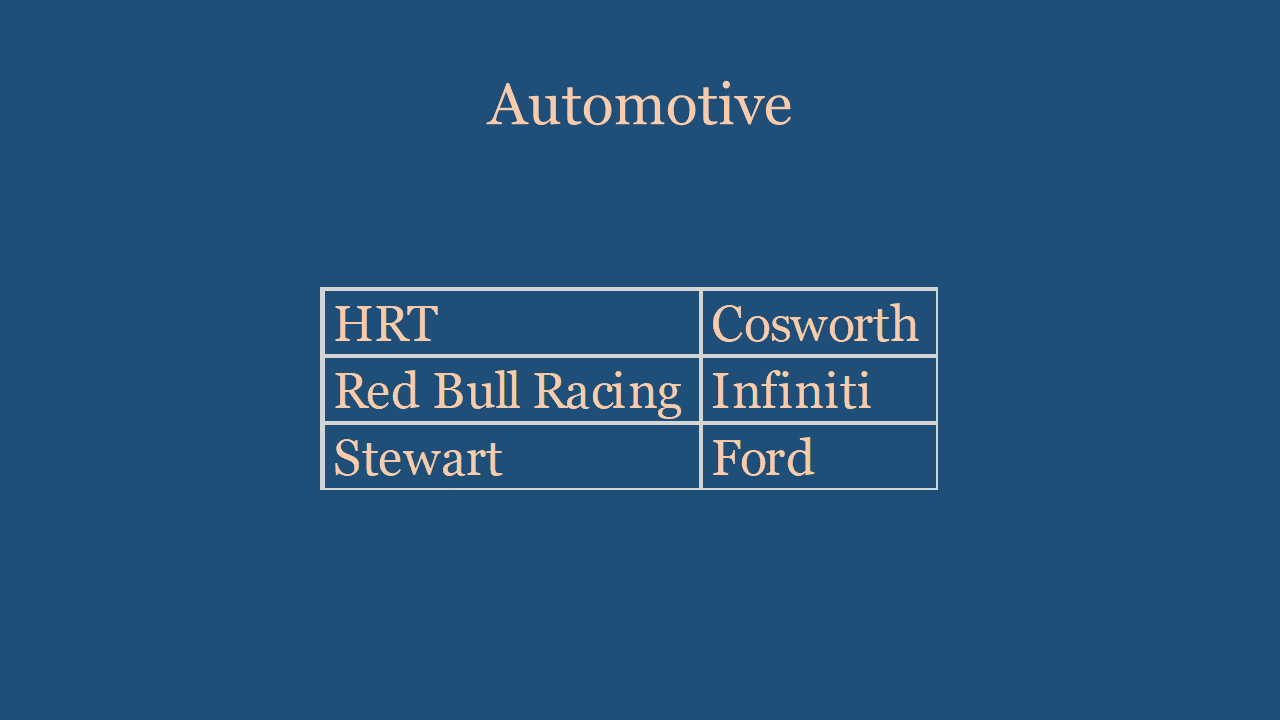

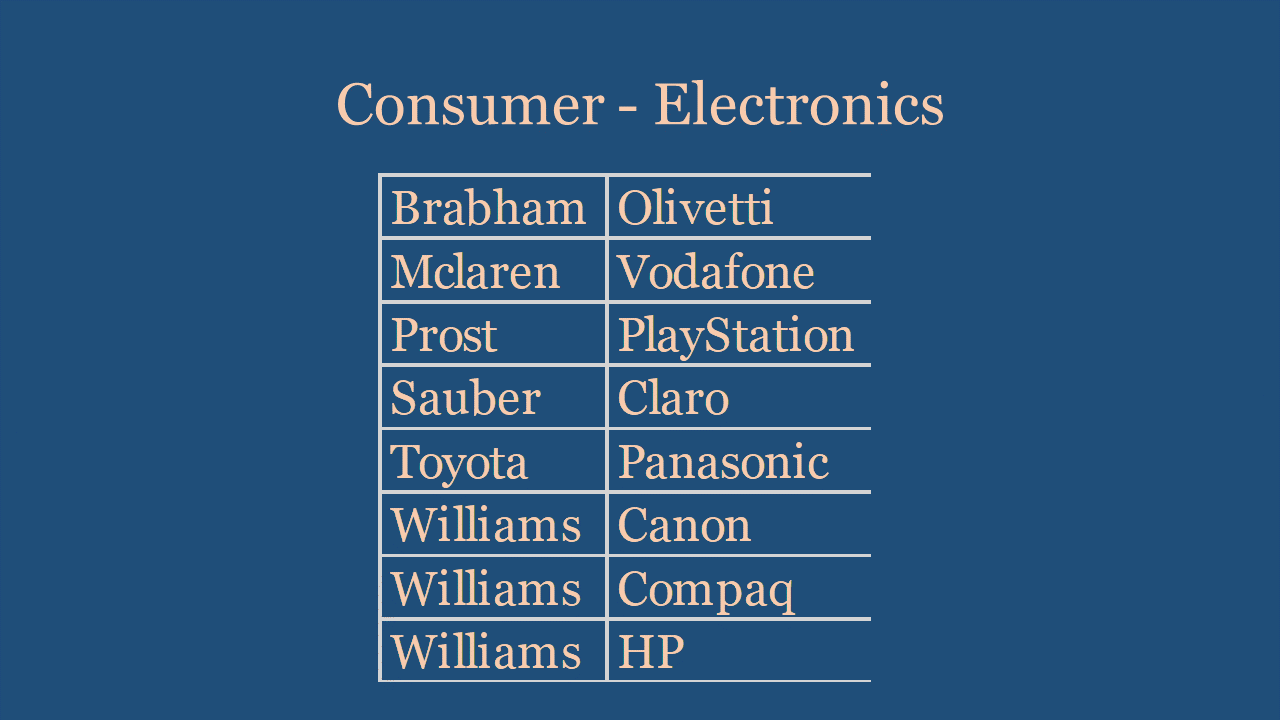

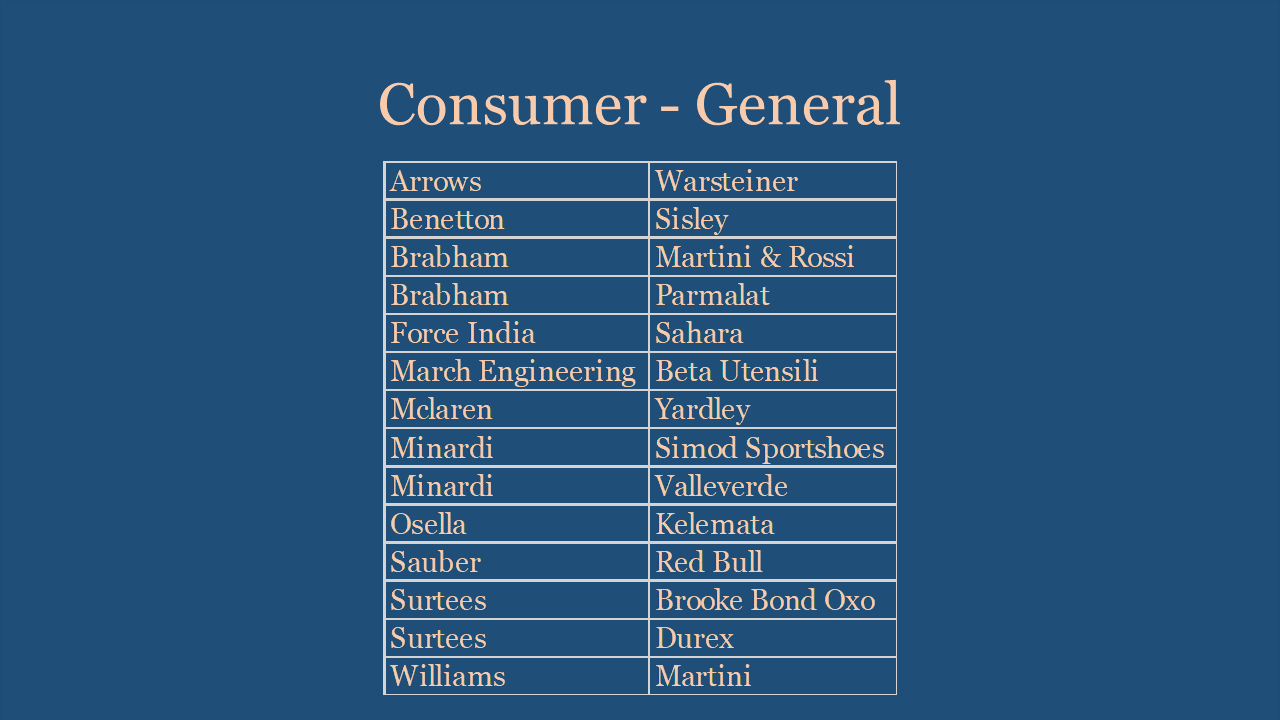

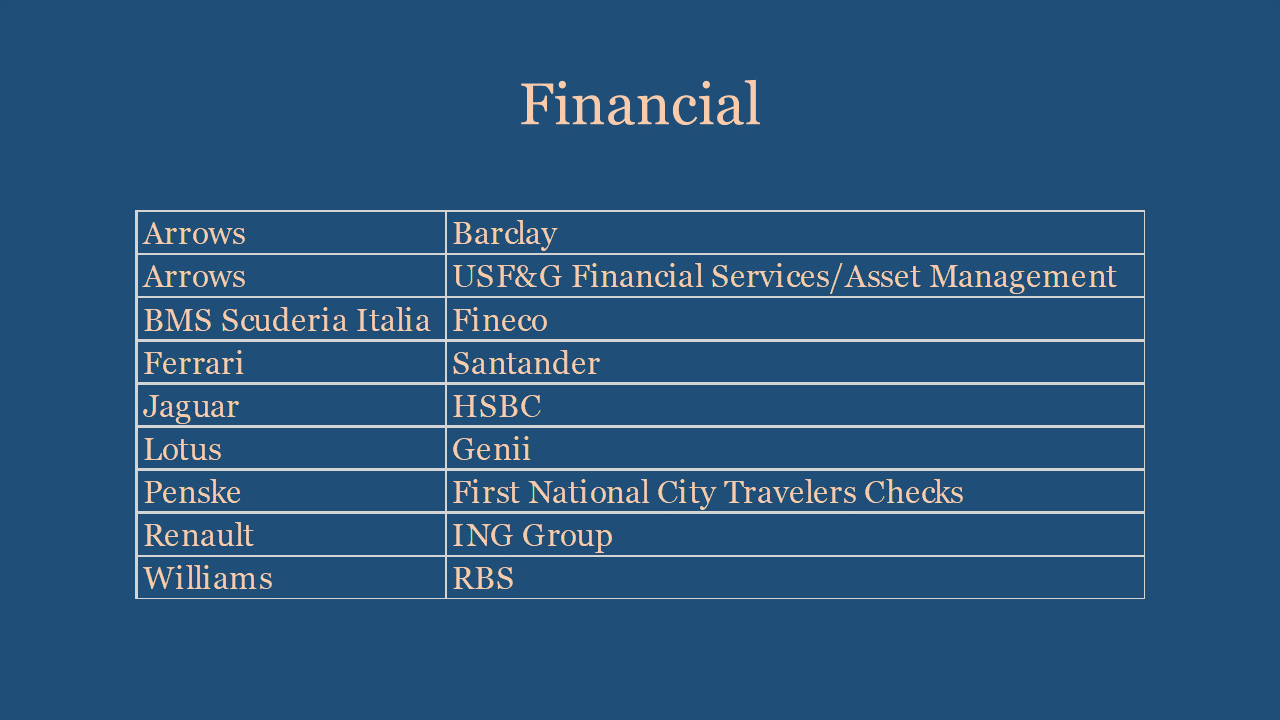

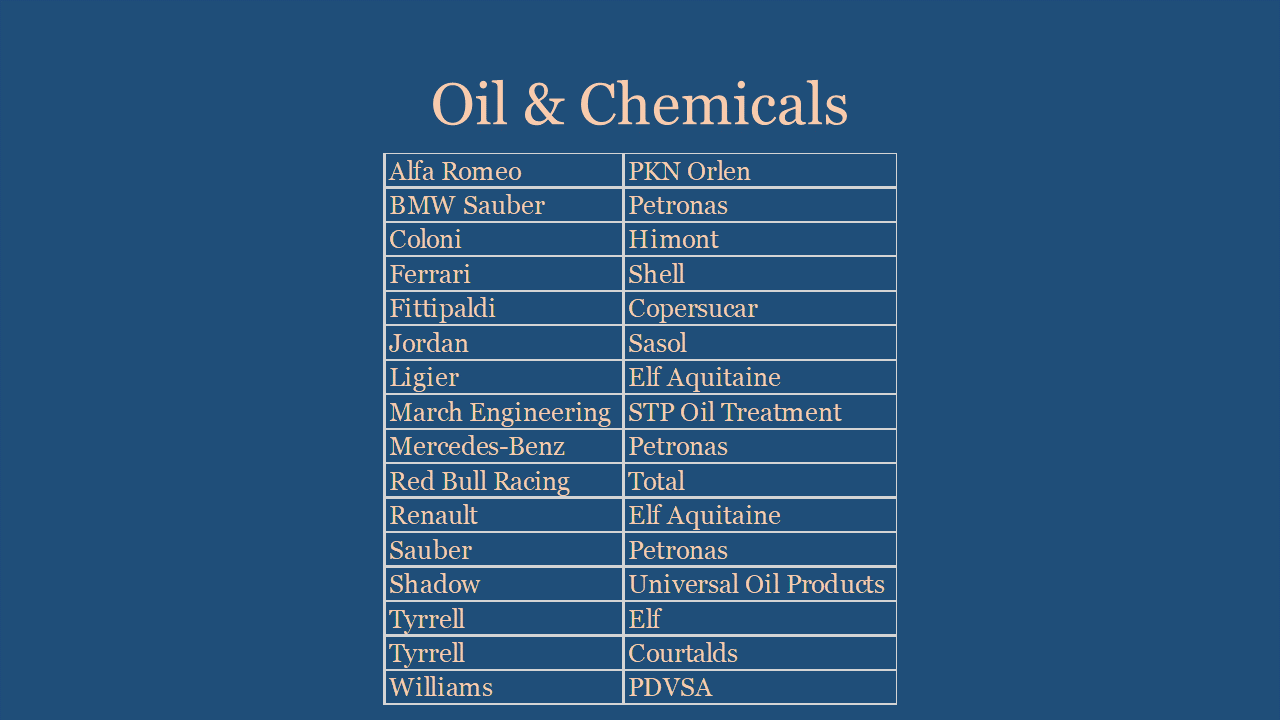

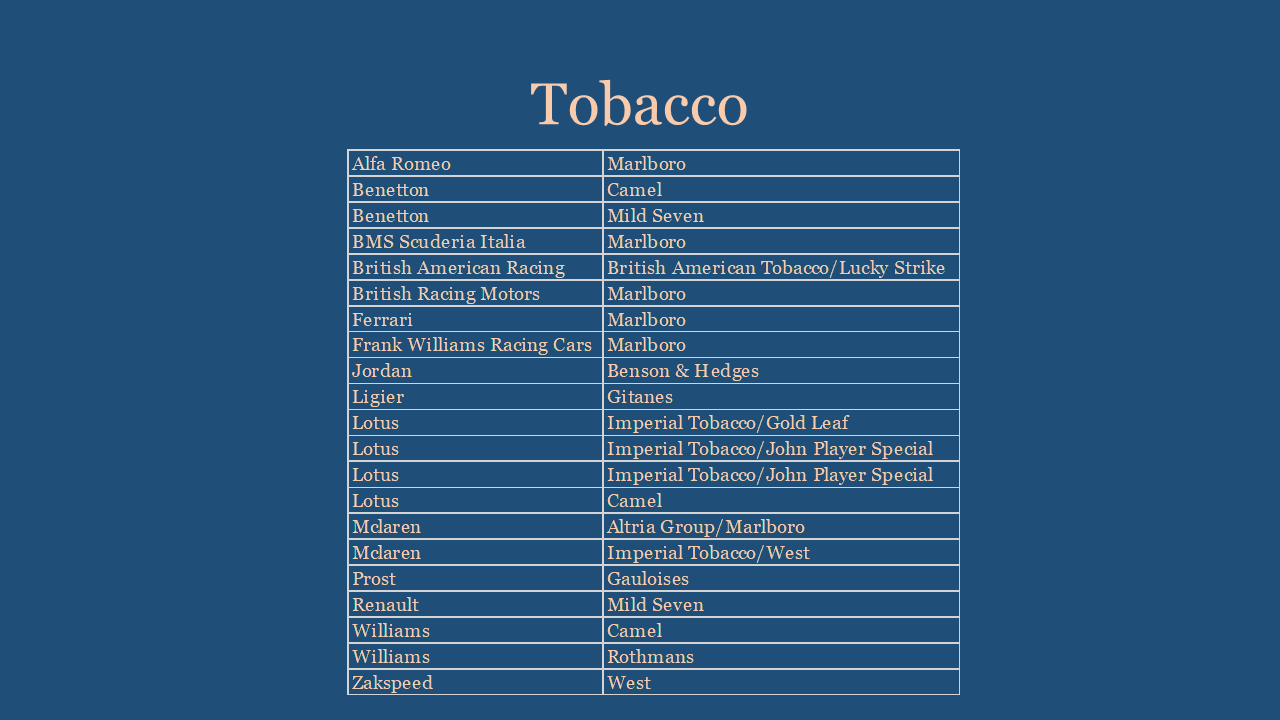

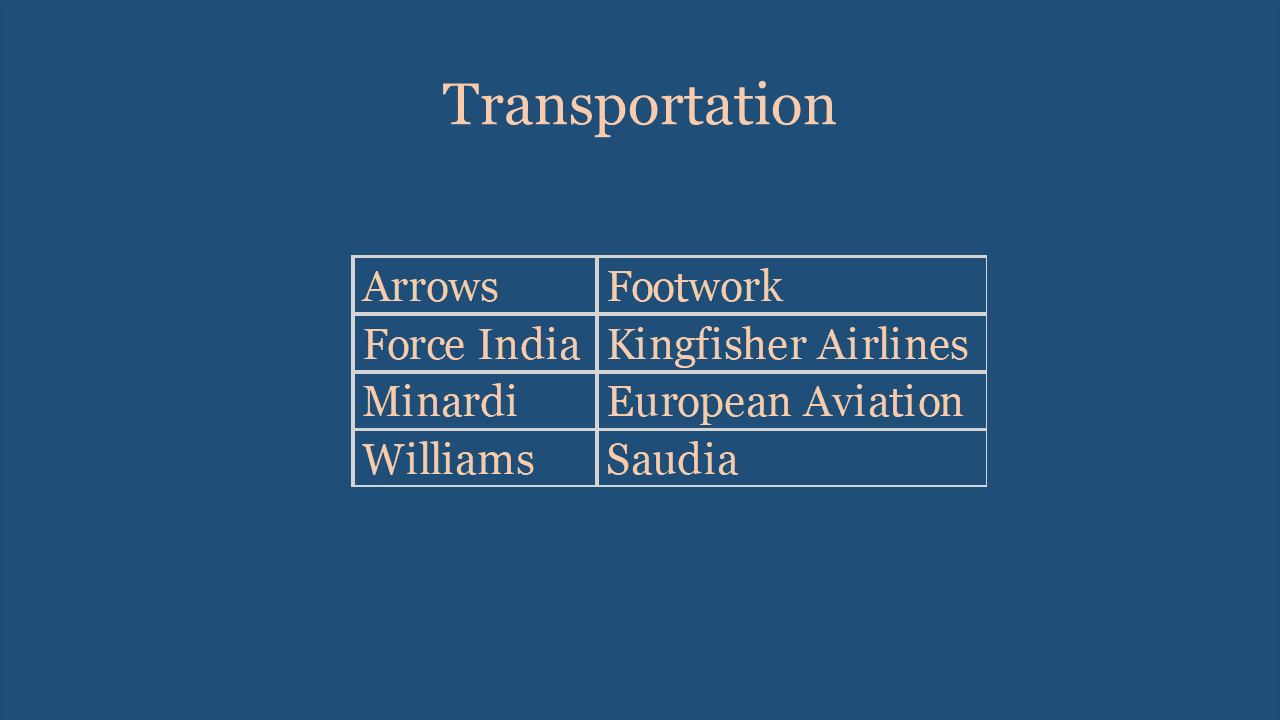

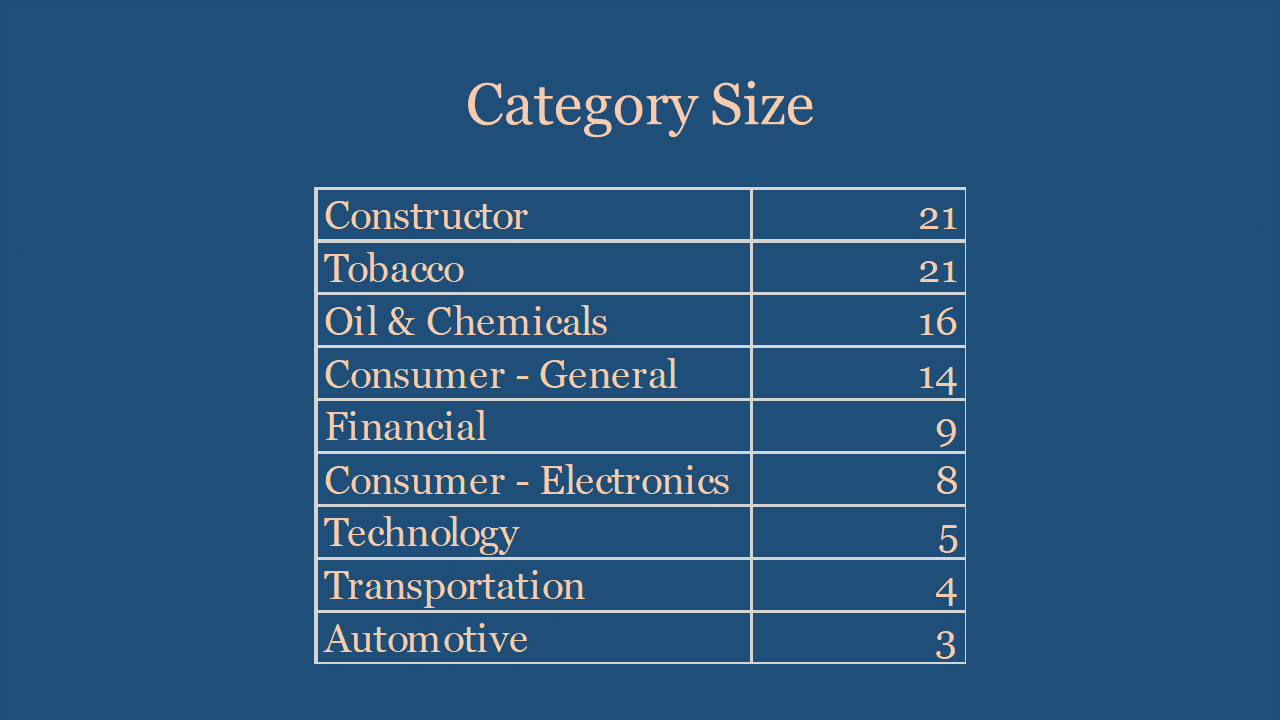

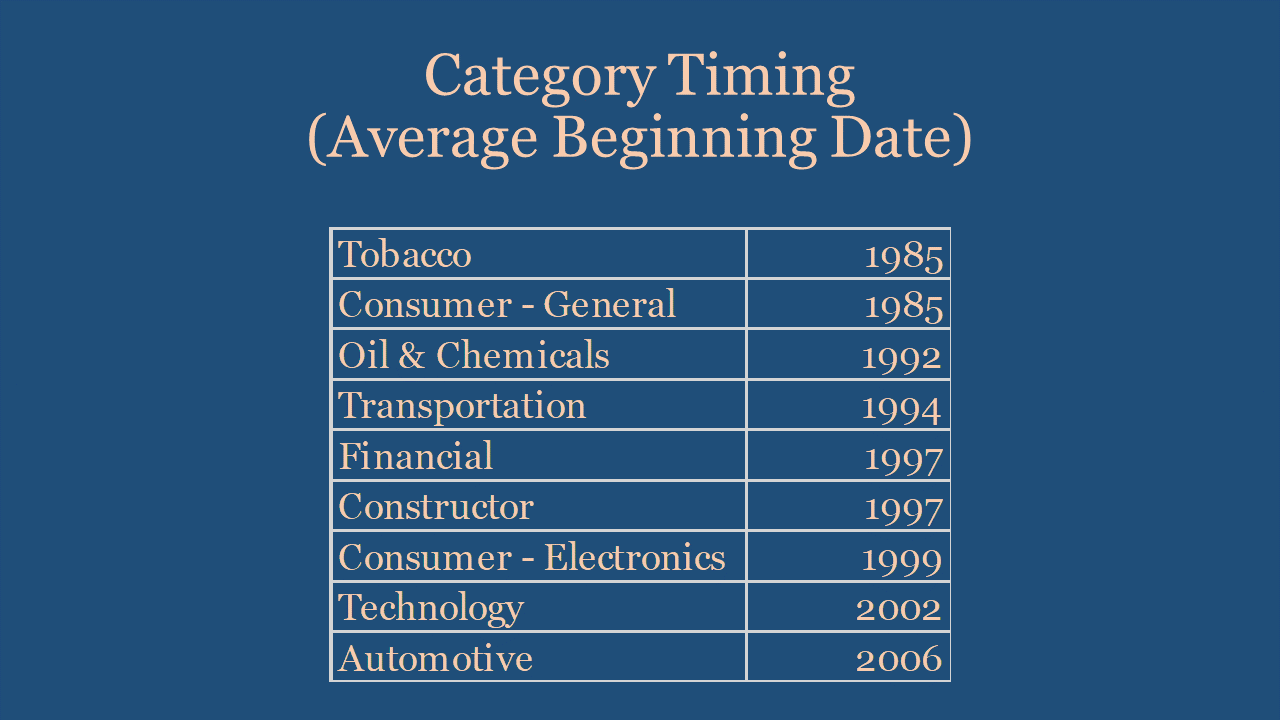

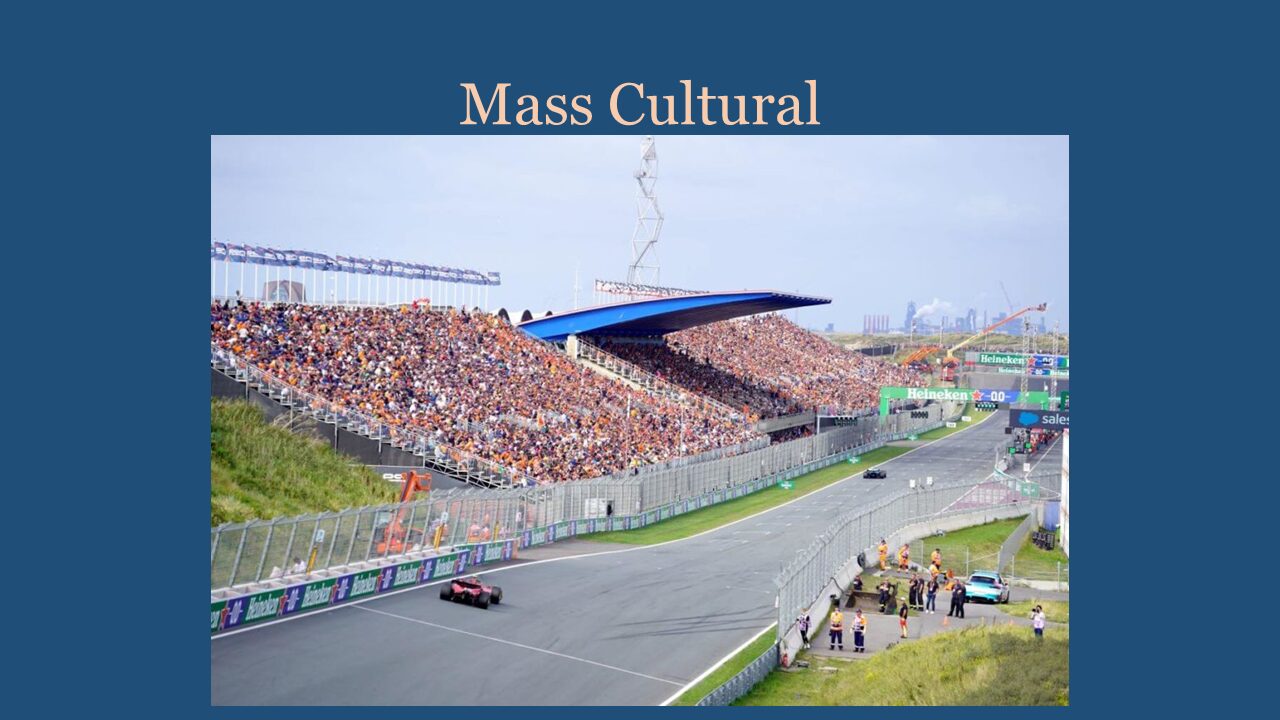

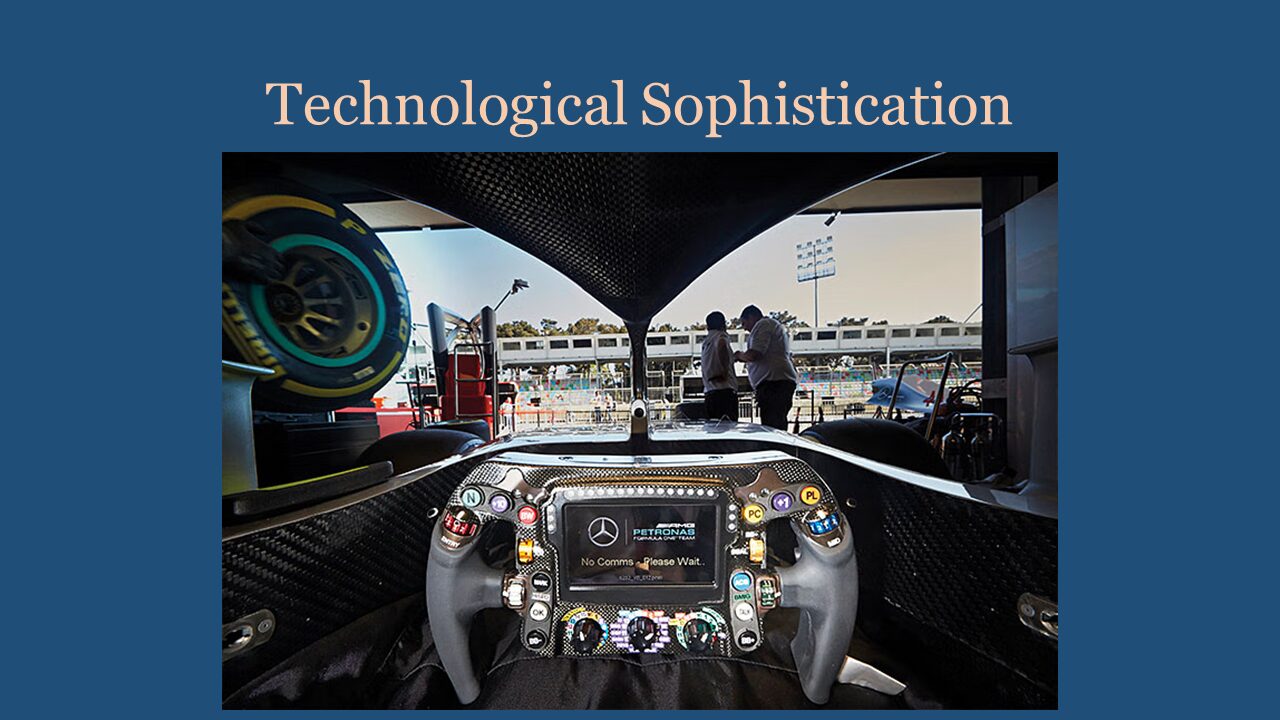

Skip McGoun examines Formula One on-track and on-vehicle sponsorships through the post-WWII period to show the evolution of the cultural appeal of the series.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Elton G. “Skip” McGoun is an Emeritus Professor of Finance at Bucknell University and a former visiting professor at the University of Donja Gorija in Montenegro. He has presented and published on both finance history and culture and automobile history and culture and served as area chair of the Vehicle Culture Section of the Popular Culture Association.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Like many research archives, the IMRRC collects selectively, not comprehensively. We don’t have the staff and space required to collect, process, and store EVERYTHING racing-related: the endless t-shirts and caps alone would overwhelm us! So, we focus on collecting items of greatest research value: books, periodicals, programs, archives of racing organizations and teams, personal papers, and photographs. But, we still want to build representative collections of other types of racing materials. Diecast and plastic models fall into the “representative” category, and while we don’t collect them comprehensively, they feature prominently at the Center. In fact, current diecast displays include a historical overview of Formula 1 cars, a selection of Richard Petty cars, and a case of McLaren F1 cars promoting our upcoming gala in honor of Zak Brown, who is receiving the 2024 Cameron R. Argetsinger Award.

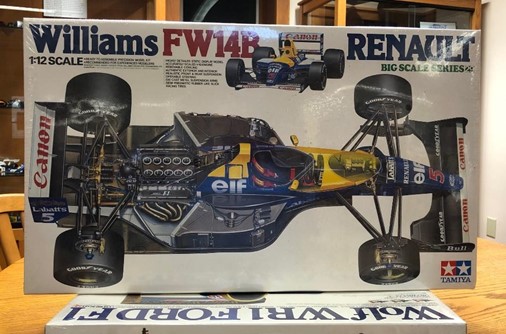

To many, Tamiya is synonymous with modeling excellence. Tamiya is well-known for its finely-detailed models of aircrafts, cars, ships, and armor, as well as radio-controlled and diecast cars. Many of us have experienced the fun/frustration of assembling and painting a Tamiya model. Recently, thanks to a generous donation from Barbara Carson, widow of the late Robert D. Carson, of 98 model Formula One cars ranging from a 1936 Auto-Union to a 2004 Ferrari piloted by Michael Schumacher, we were excited to add several new Tamiya models to our collection.

The majority of the Tamiya diecast cars are from the company’s “Collector’s Club” collection. From an historical perspective, the highlights are 1:20 models of the Lotus 102B, which raced in 1991, and the Lotus 107B, which raced in 1992. Aside from being beautiful replicas of the cars, they are interesting because Tamiya sponsored Lotus from 1991-1993. Tamiya’s logo is prominently displayed on both cars’ wings – an accurate representation of the cars’ livery in those years.

Other 1:20 Collectors Club models in the donation include models featuring prominent drivers Michael Schumacher, Ayrton Senna, and Jean Alesi. All the models came complete in their original packaging and display cases.

Another interesting diecast car included in the gift is this 1/12 model of the Honda F-1 RA272. Designed by Yoshio Nakamura and Shoichi Sano, this car raced during the 1965 Formula One season, driven by Richie Ginther. The RA272 was the first Japanese car to win in Formula One, a fact proudly noted on the front of the box, “1965 Mexico G.P. Winning Machine.”

Finally, thanks to the generosity of Mike Fuller, we have two unassembled plastic model kits, both from Tamiya’s 1:12 “Big Scale Series” and sealed in their original boxes. The first is a model of the Williams FW14B Renault, designed by Adrian Newey and raced by Nigel Mansell and Riccardo Patrese during the 1991 and 1992 Formula 1 seasons.

The second is a Wolf WR1 Ford F1 built for the 1977 racing season and driven by Jody Scheckter and Keke Rosberg.

As noted, the IMRRC does not collect models comprehensively: we could easily fill our facility with models alone. But, models are nonetheless essential to our holdings. Models illustrate, in an accessible way, the development of race cars over time; they are wonderful examples of racing merchandising; they show one aspect of race fans’ devotion to the sport – their desire to build/collect replicas of favorite cars. The Tamiya models specifically are evidence of Tamiya’s close relationship with F1 and Lotus. Model cars are excellent educational tools. They are also colorful, and look incredible when displayed, and we feel they enhance our exhibits and collections.

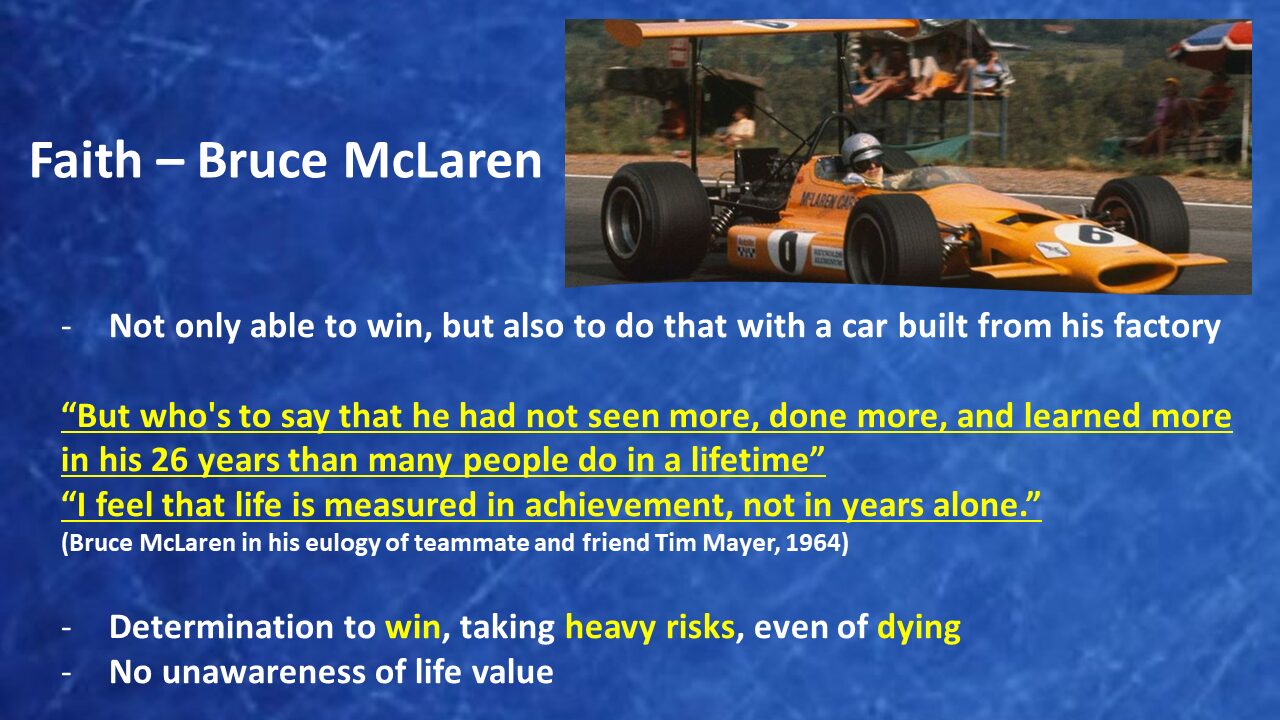

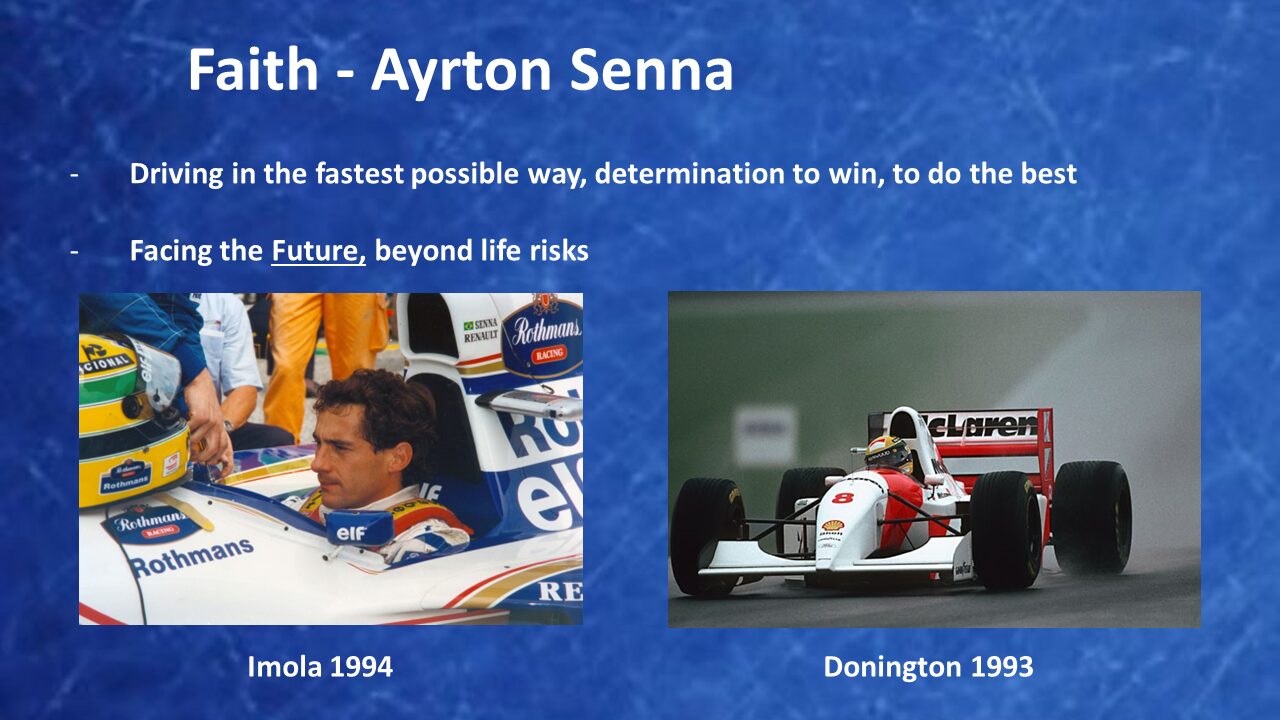

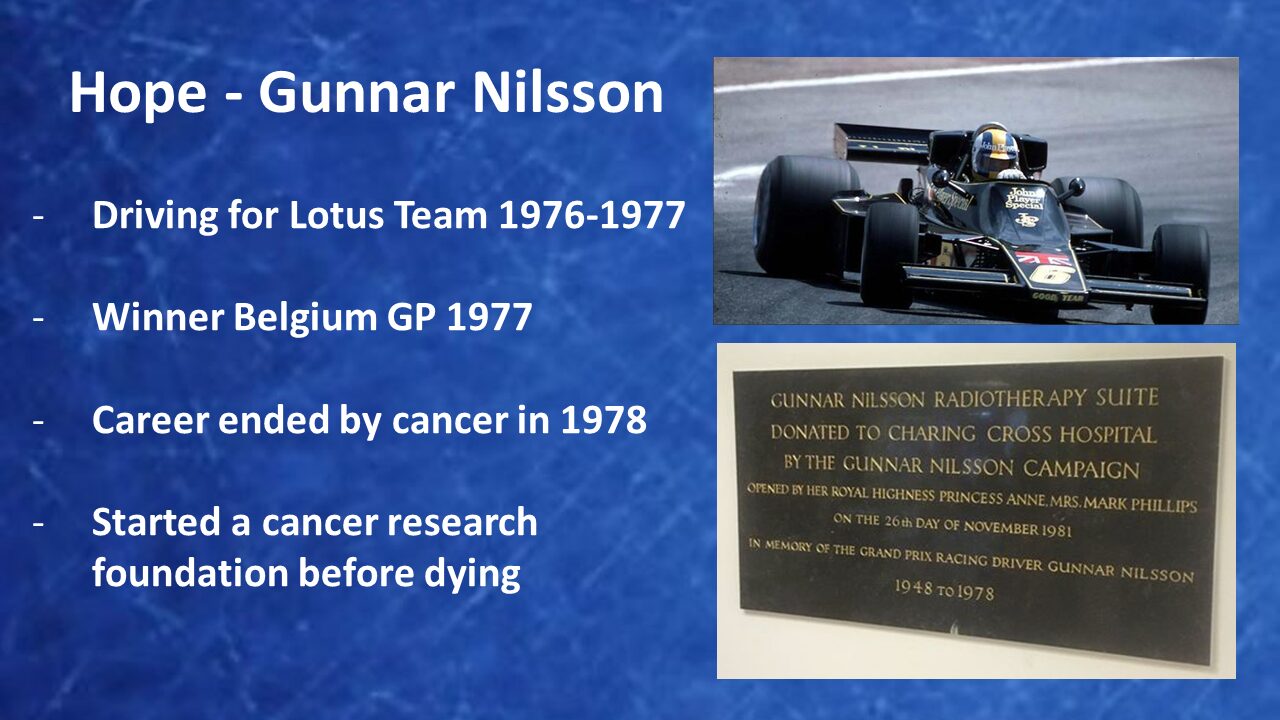

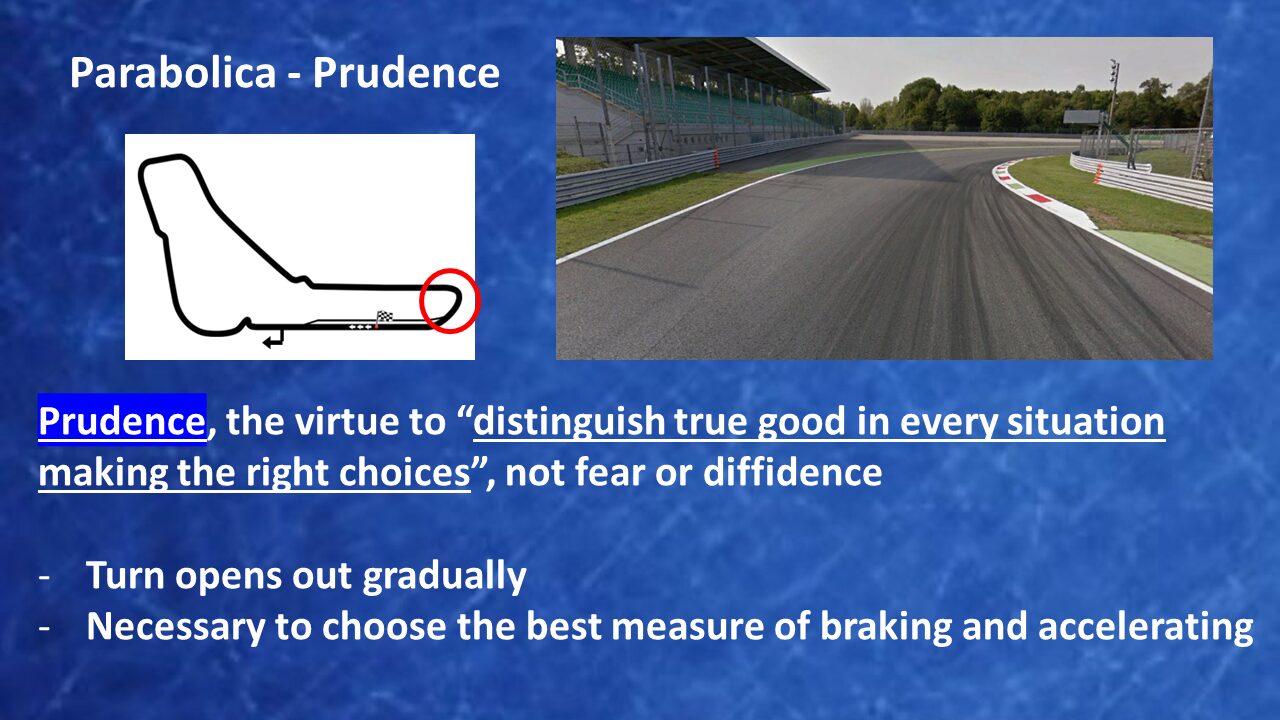

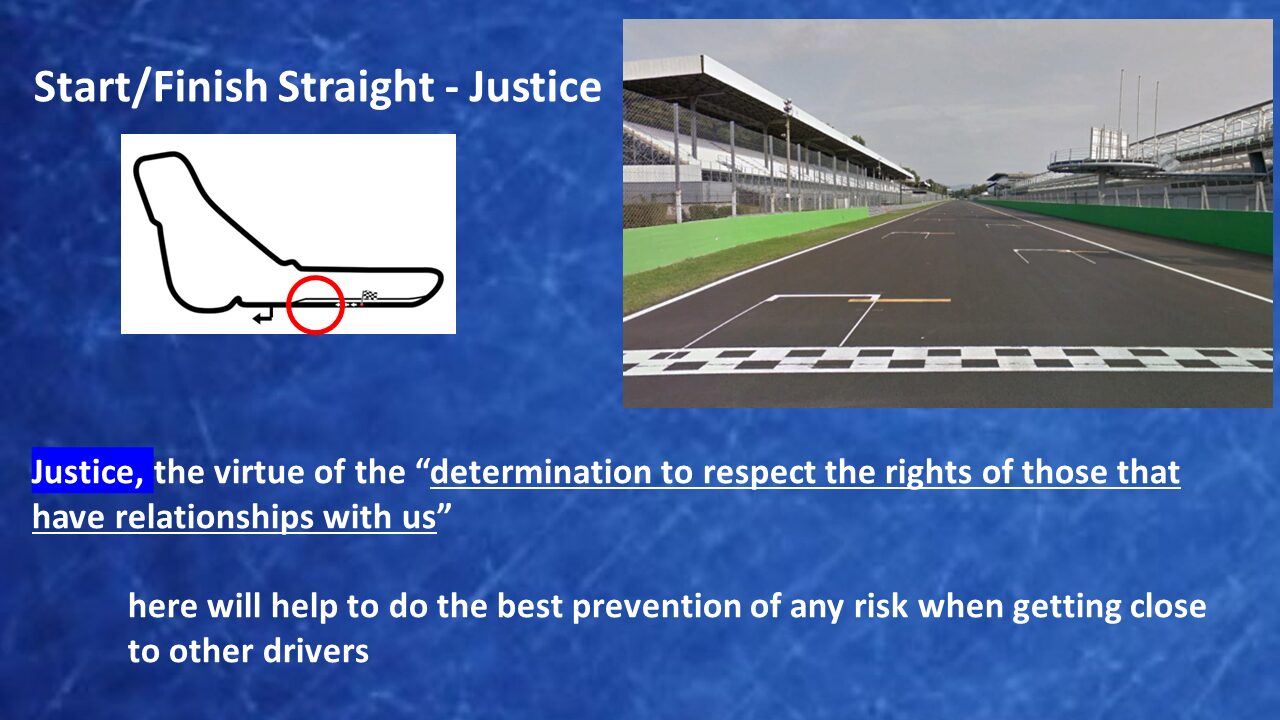

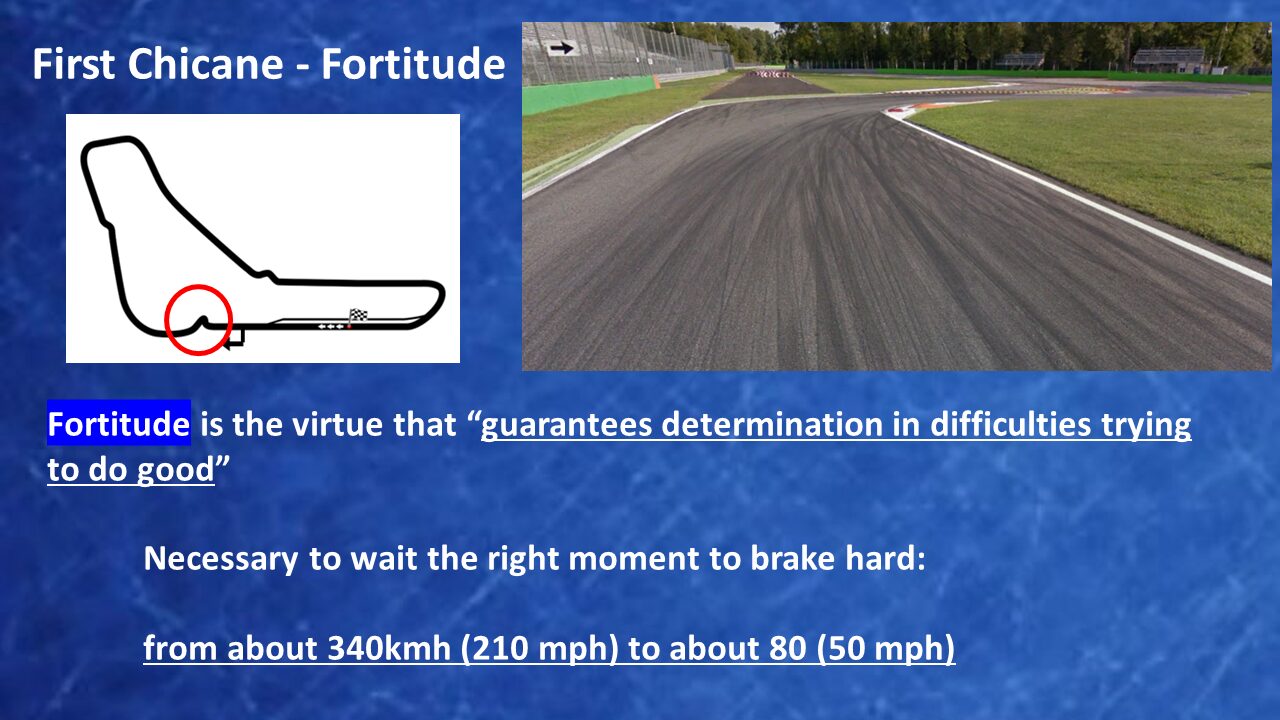

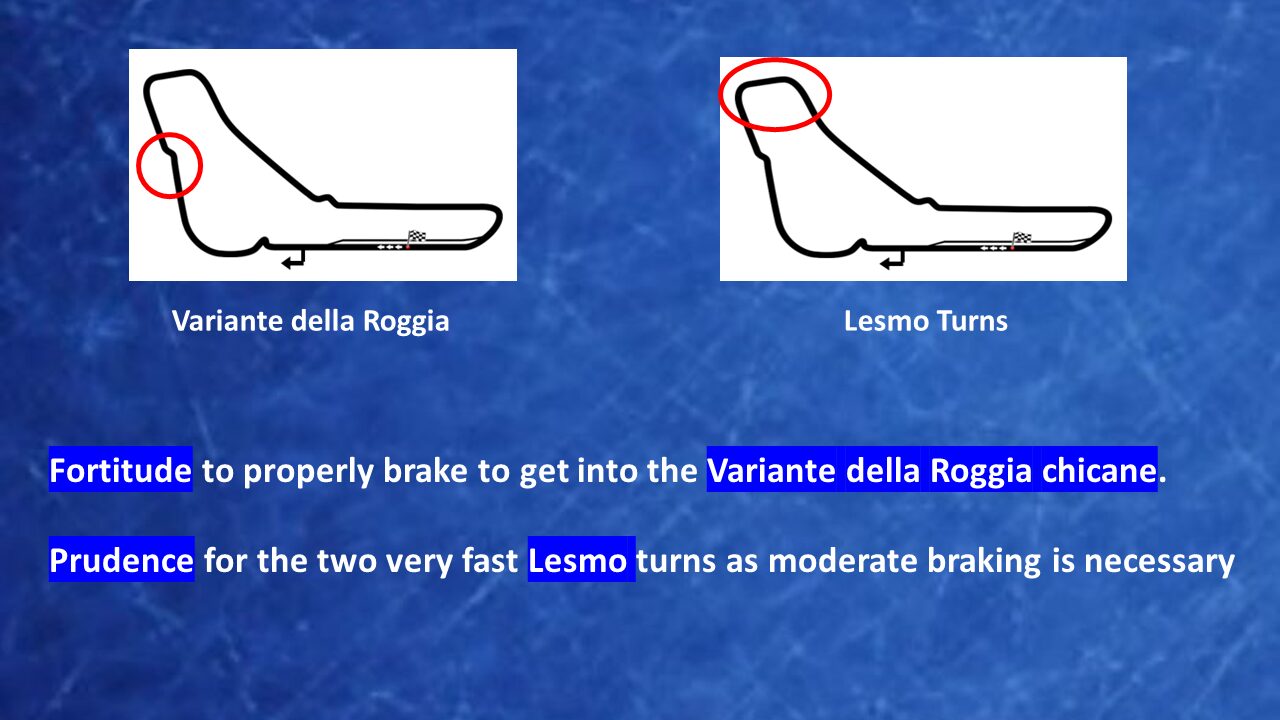

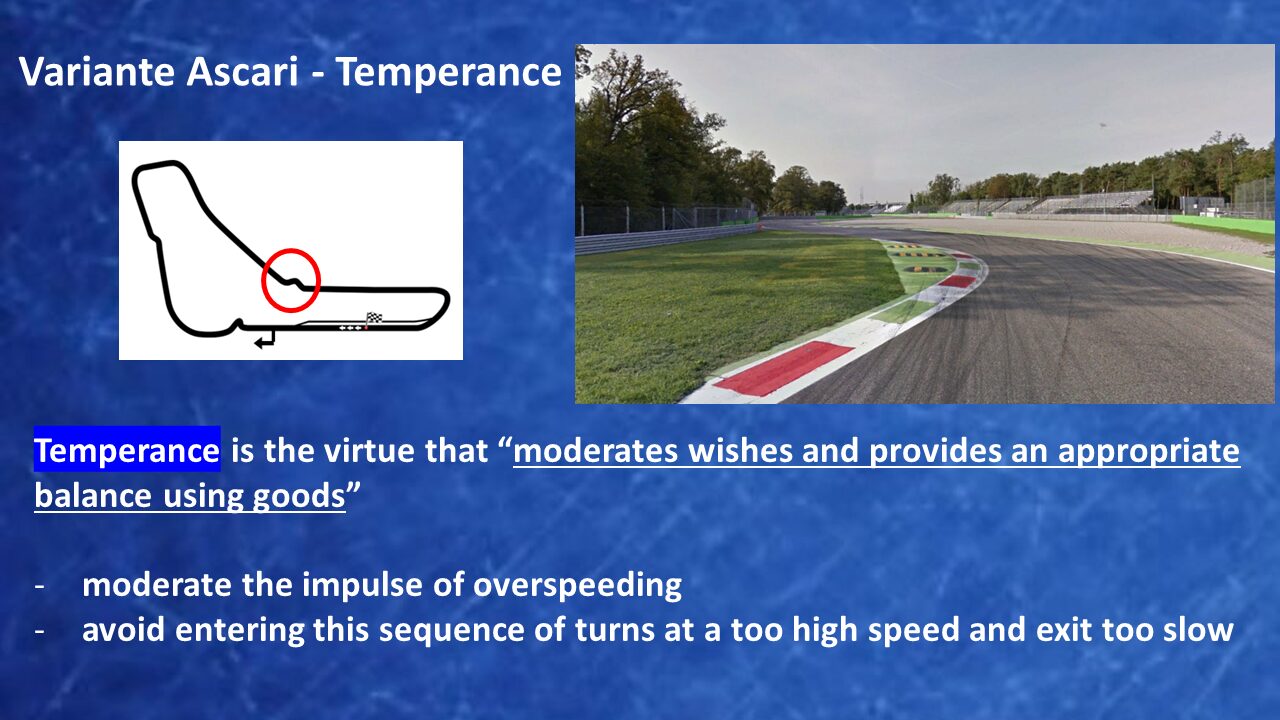

Having a strong interest and deep passion for car racing, Dr. Mario Felice Tecce analyzed Formula One seasons of the last 50 years and suggests that race car driving can be a major example of general life choices between good and bad in a joint competition to pursue the best possible.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Dr. Tecce received his M.D. and PhD. at the University of Naples, Italy, and is currently full profession of biochemistry at University of Salerno. Besides his molecular research about cancer mechanisms, he explored race car driving as a major reference paradigm of pursuing the best and of free will exercise.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

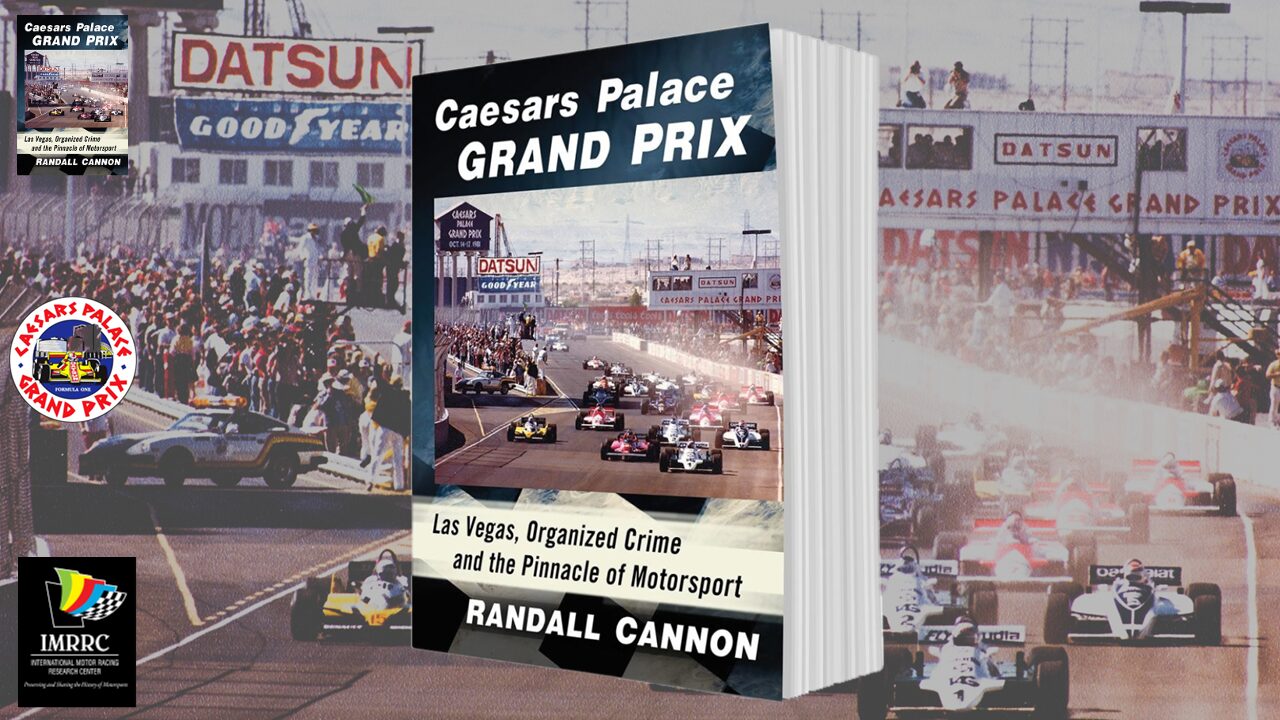

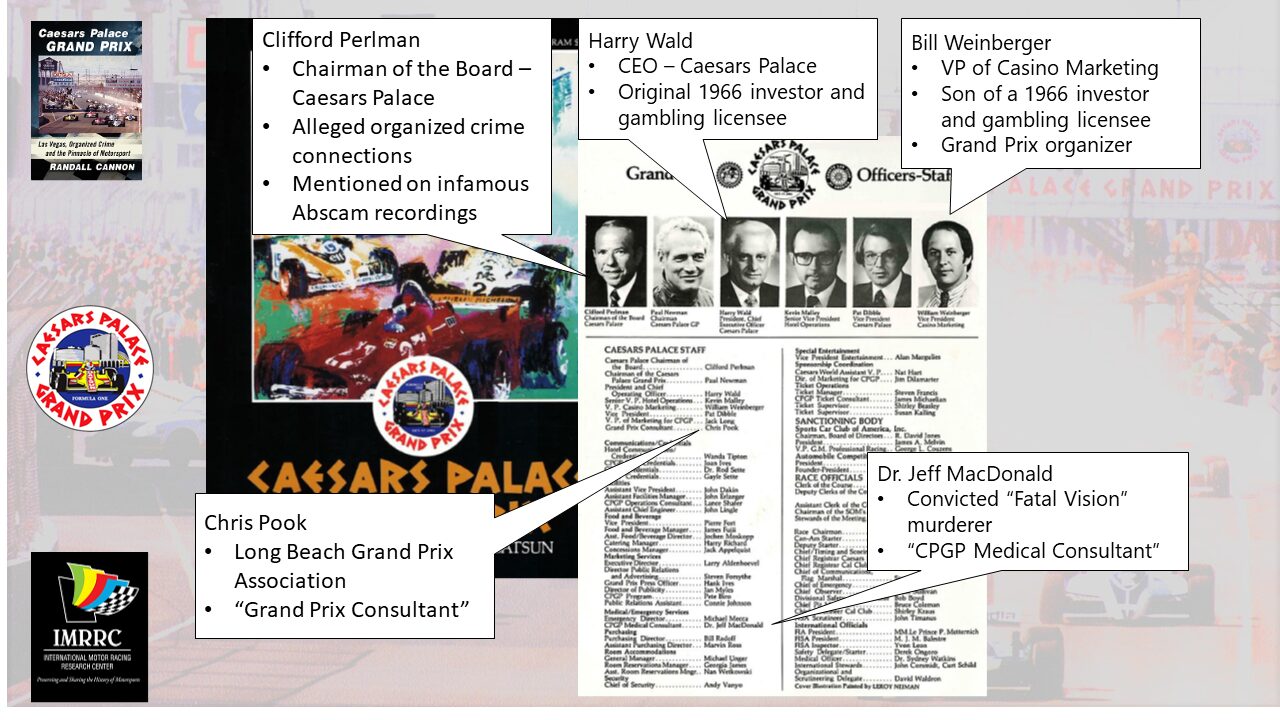

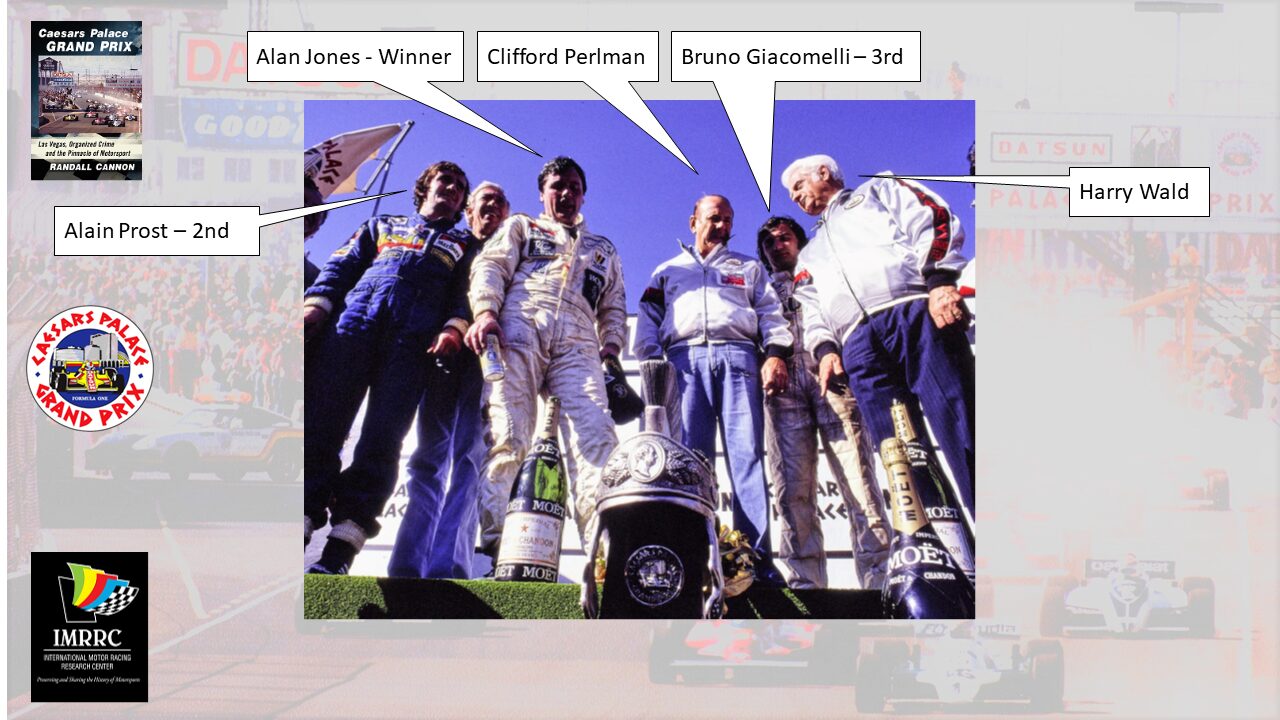

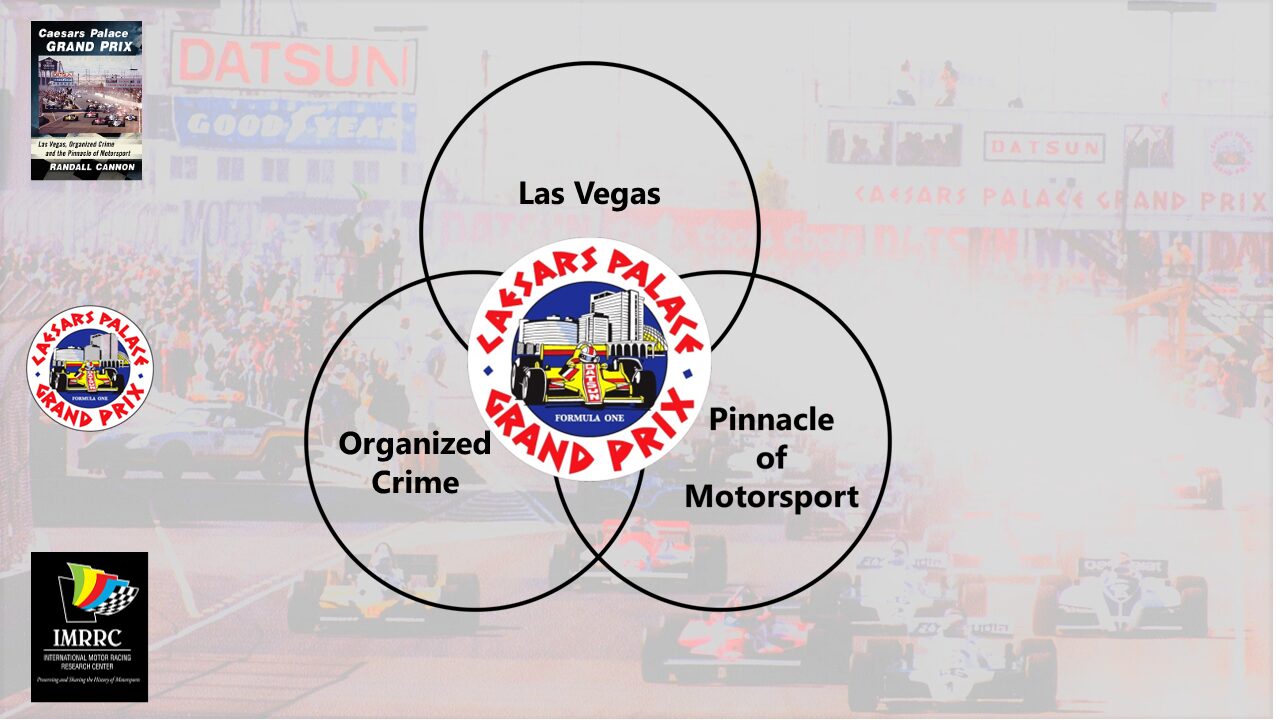

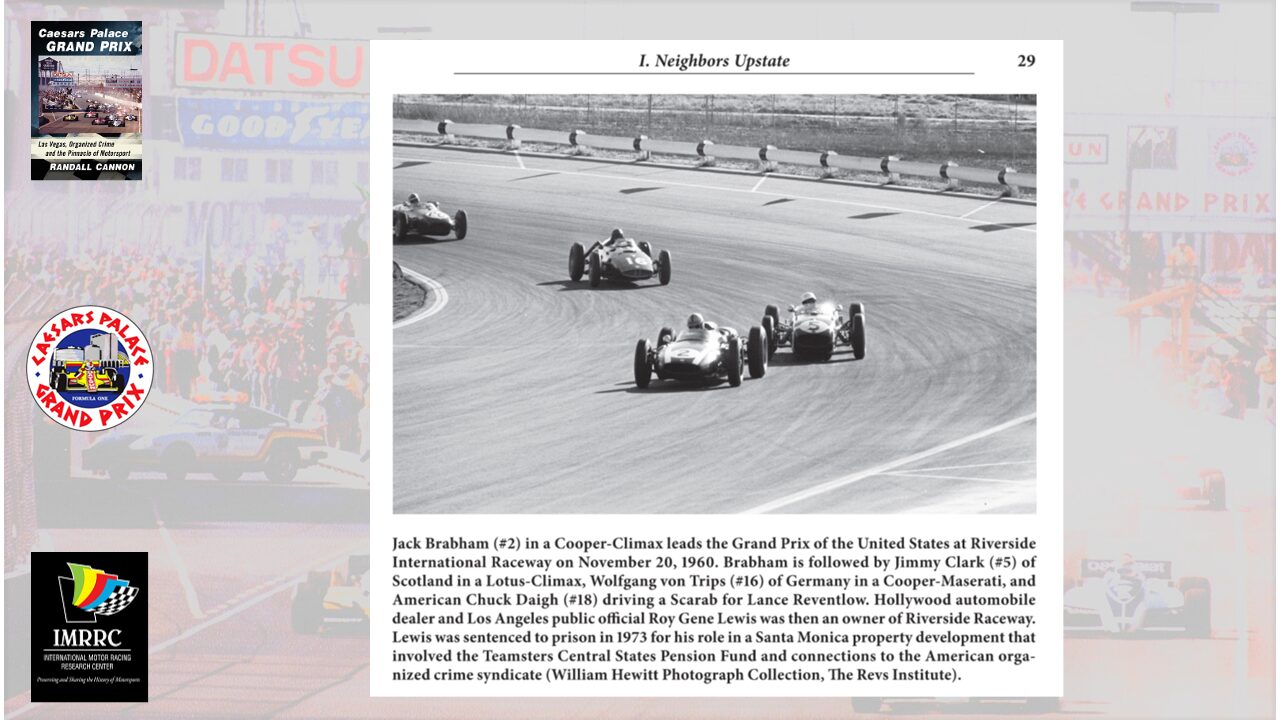

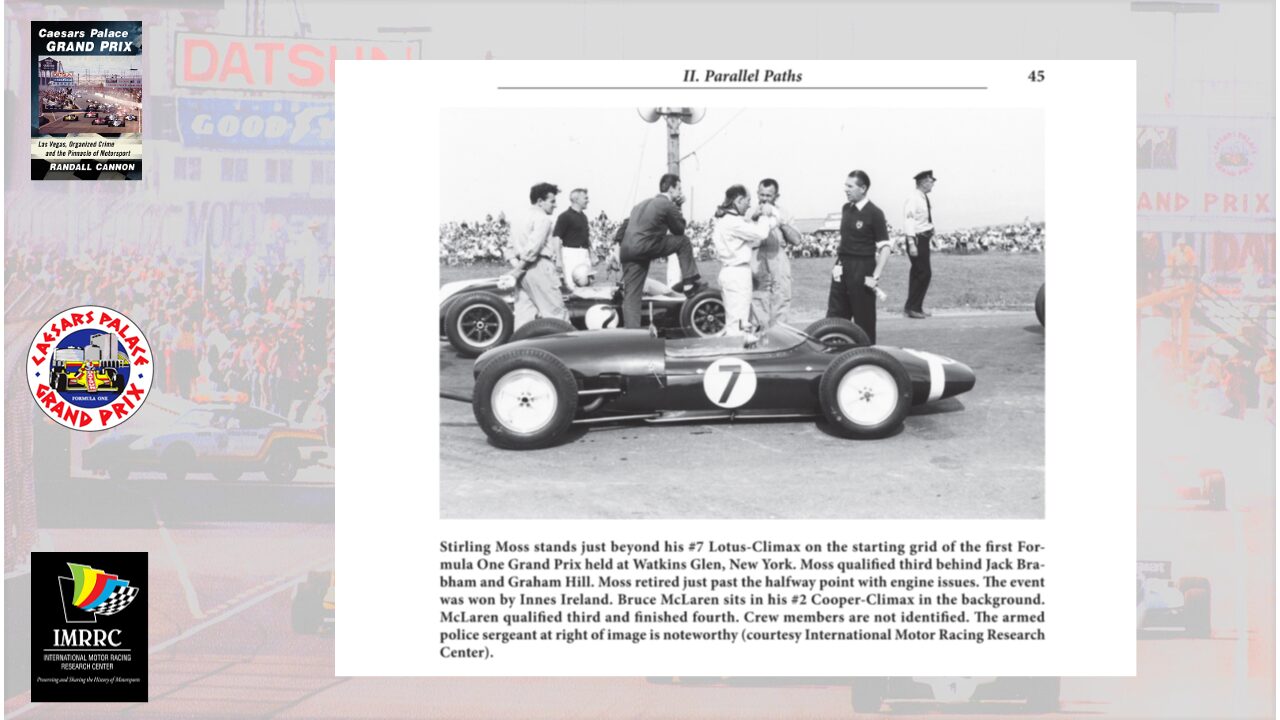

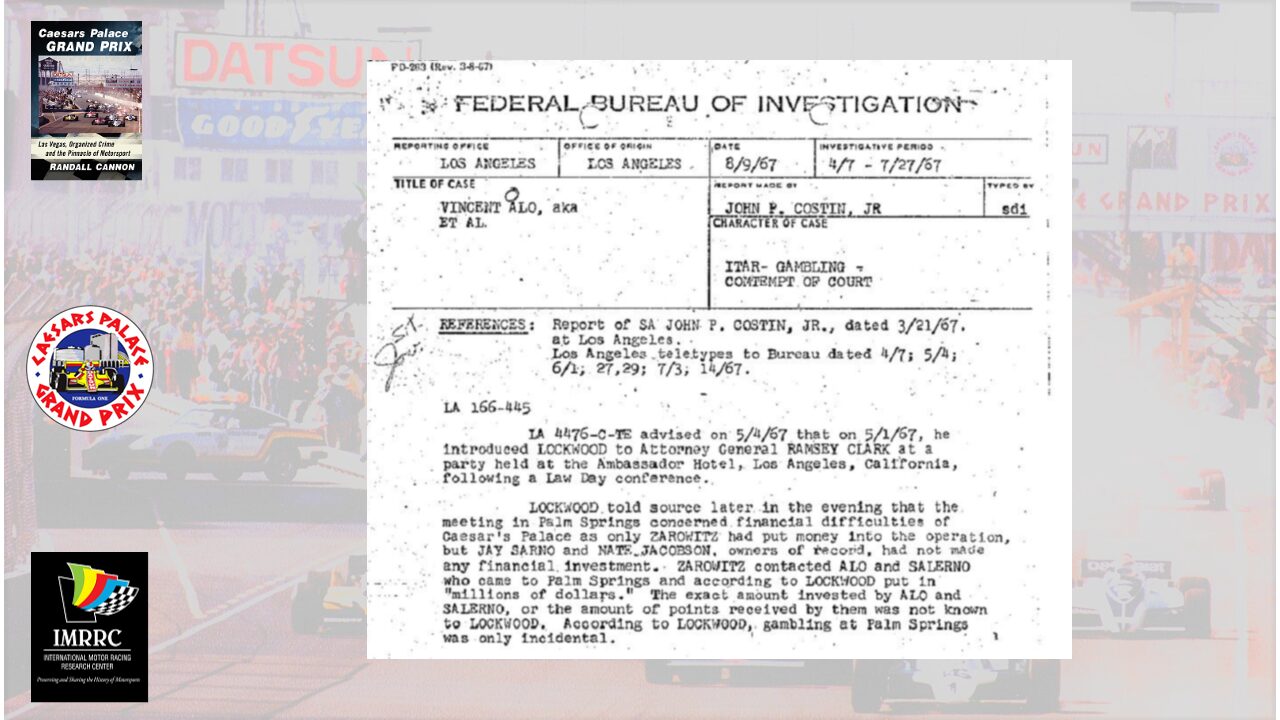

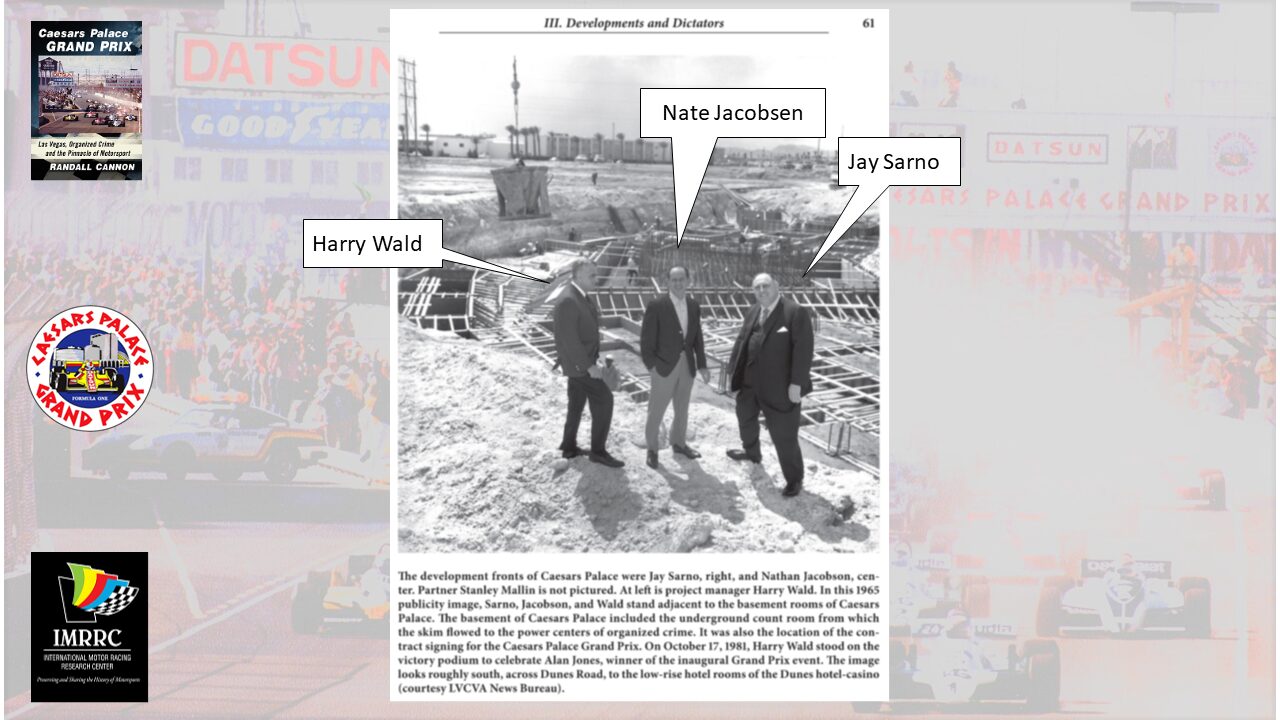

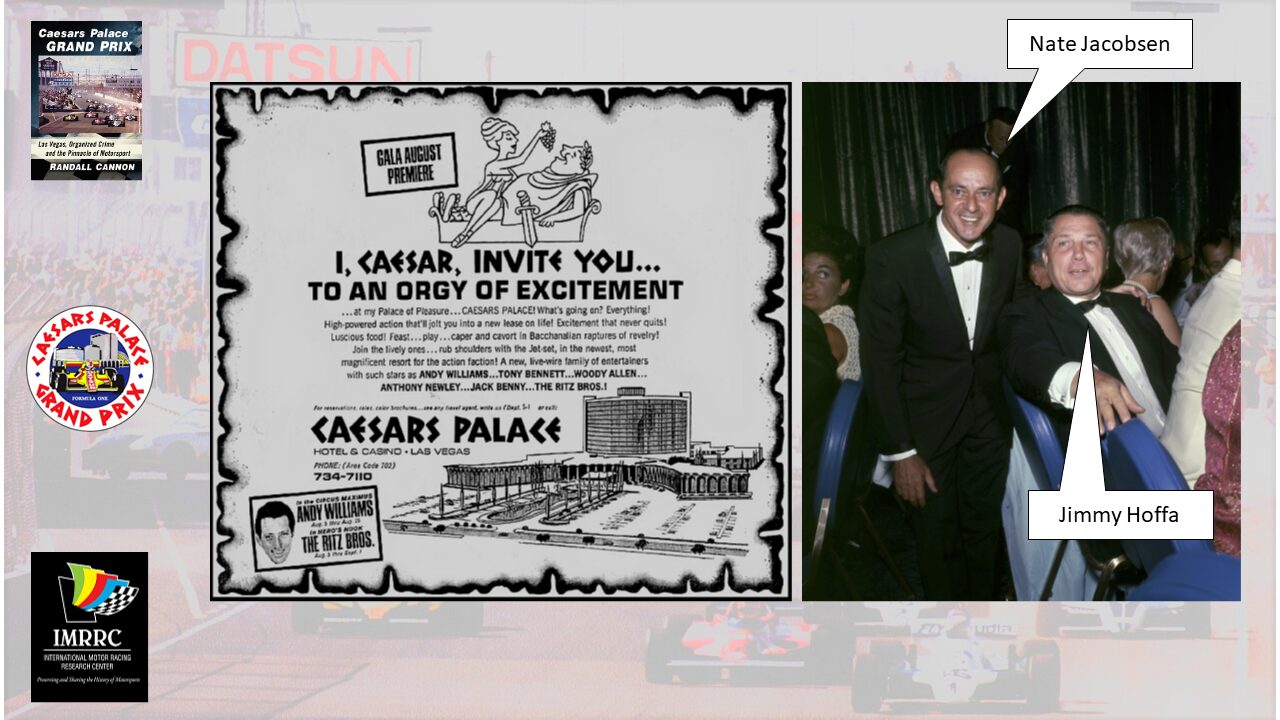

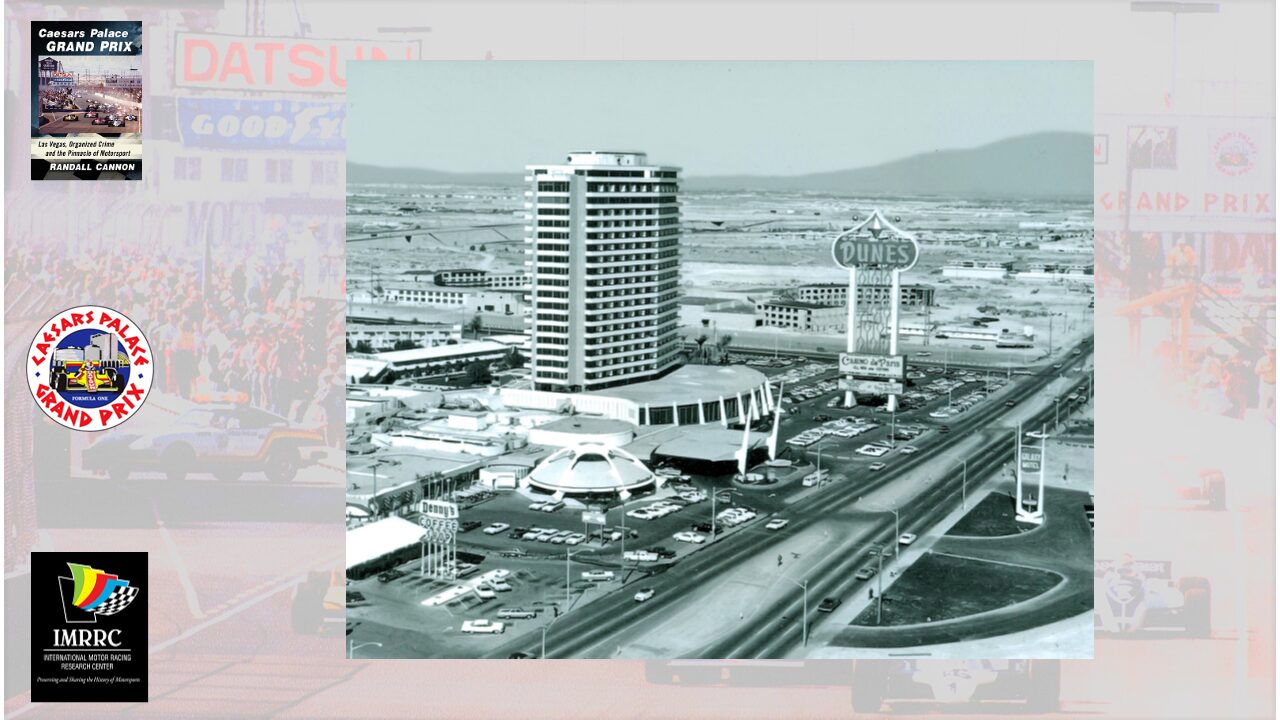

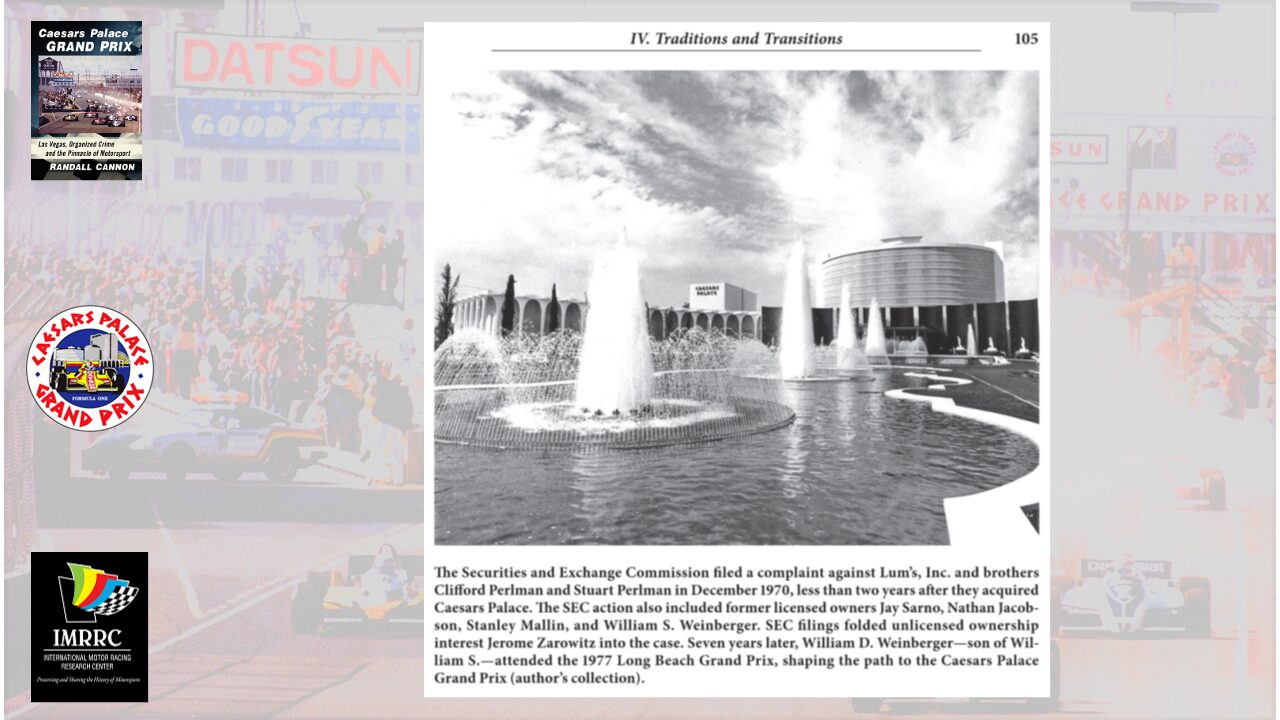

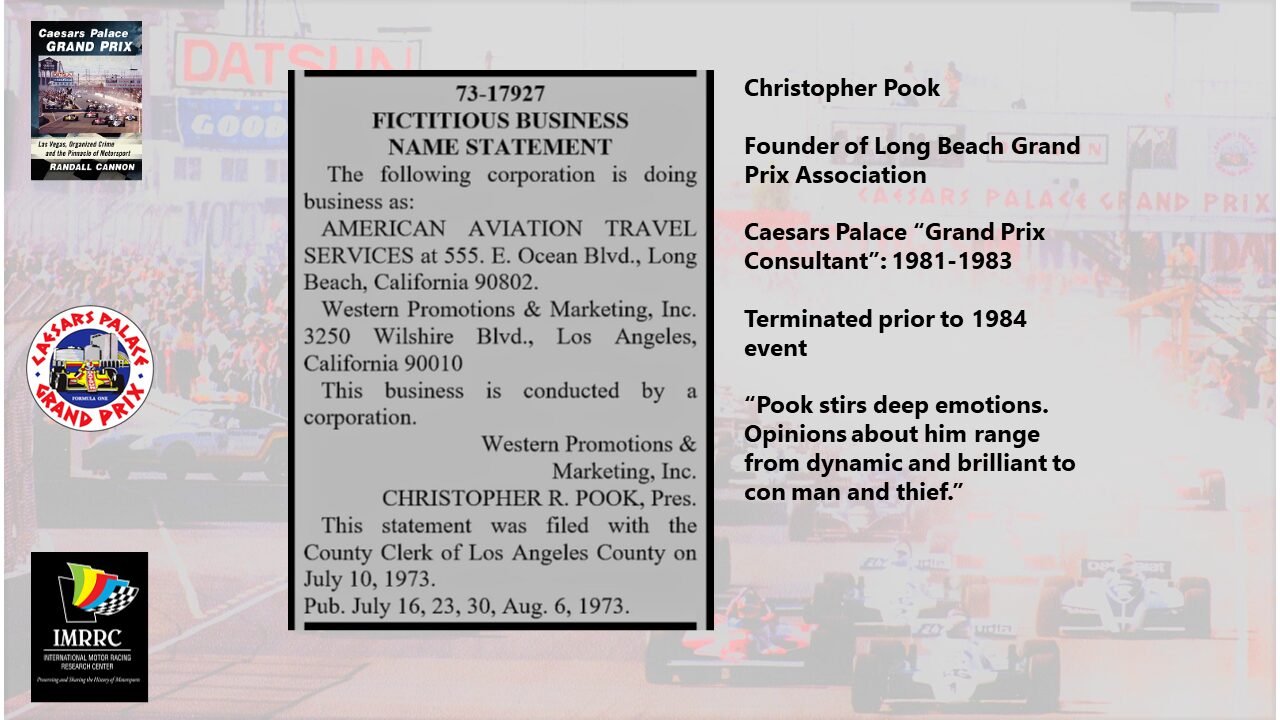

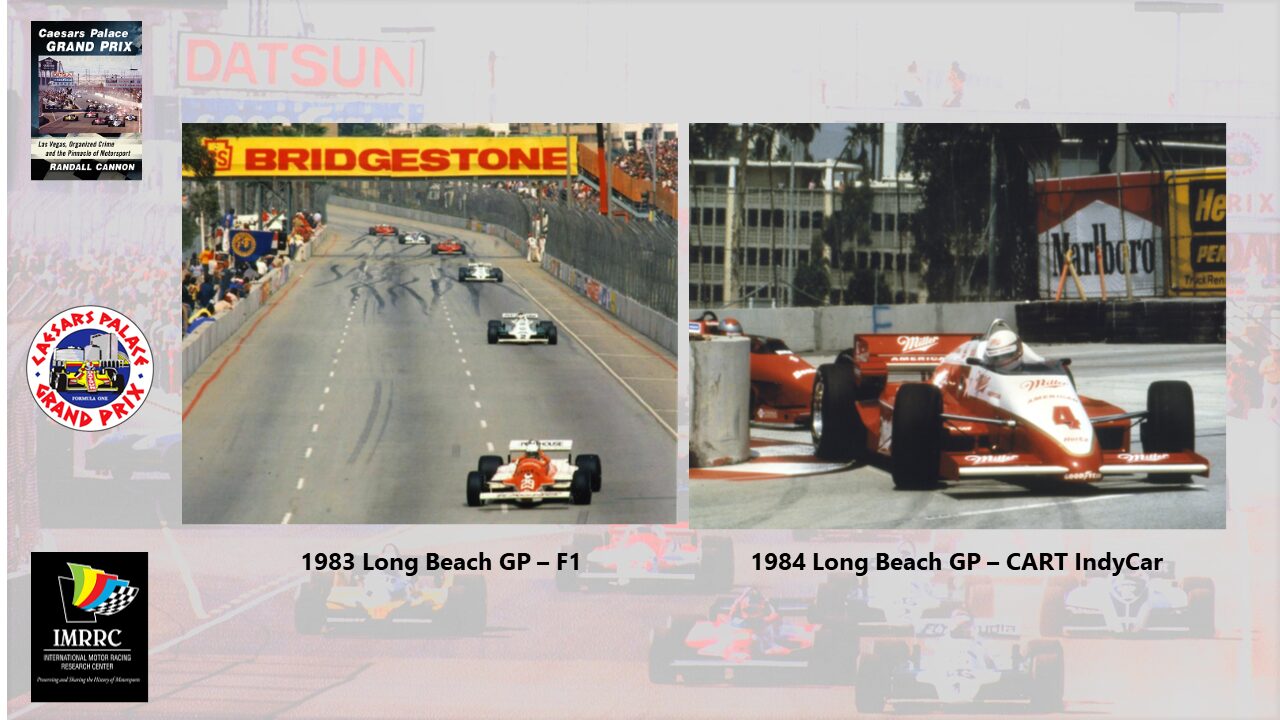

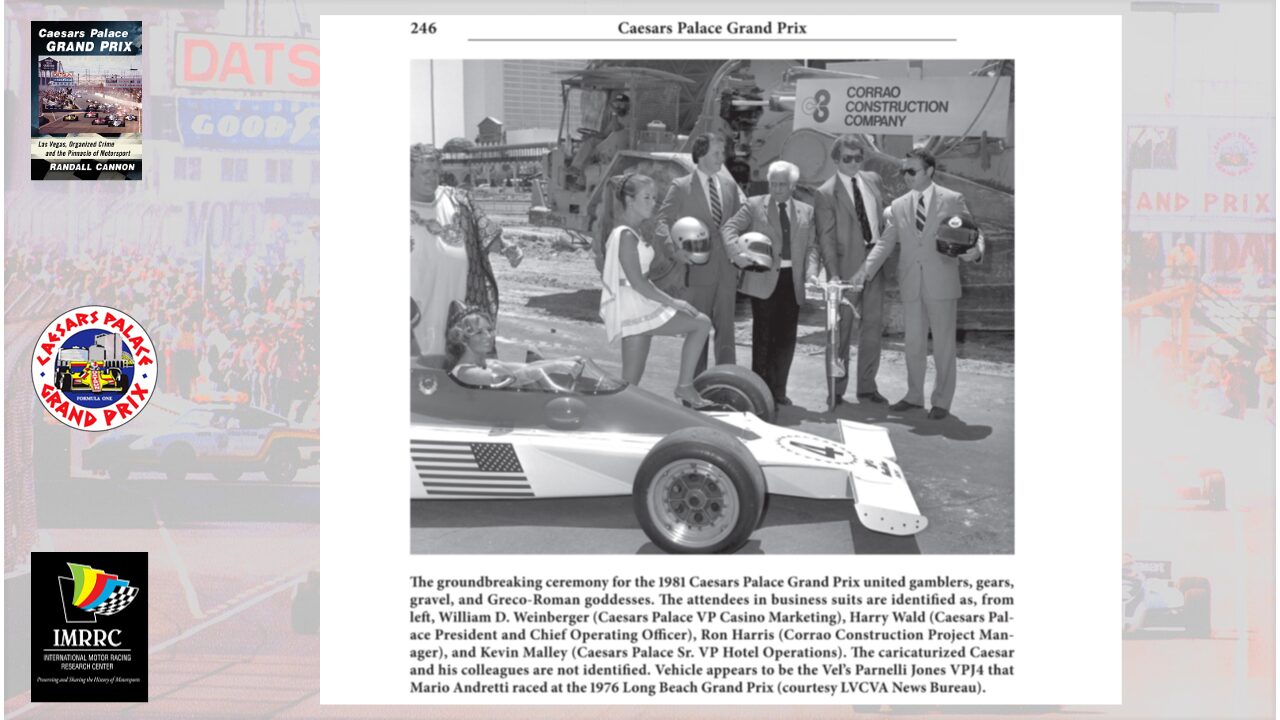

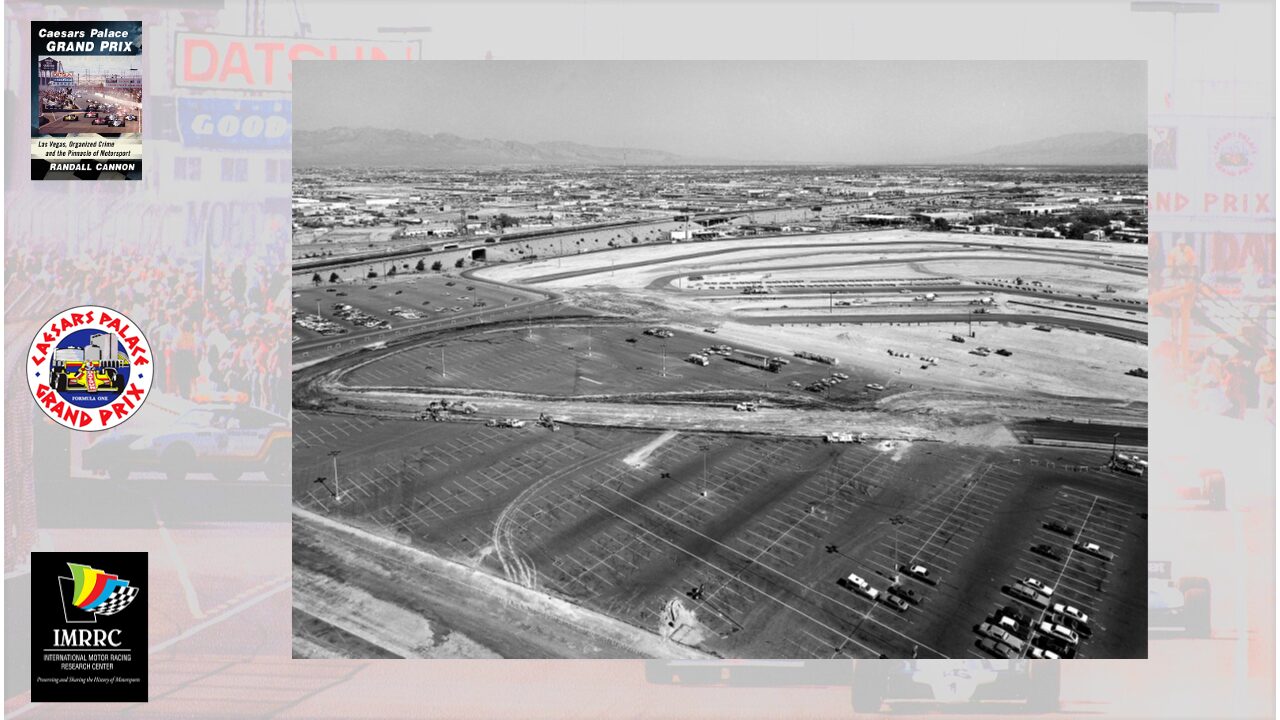

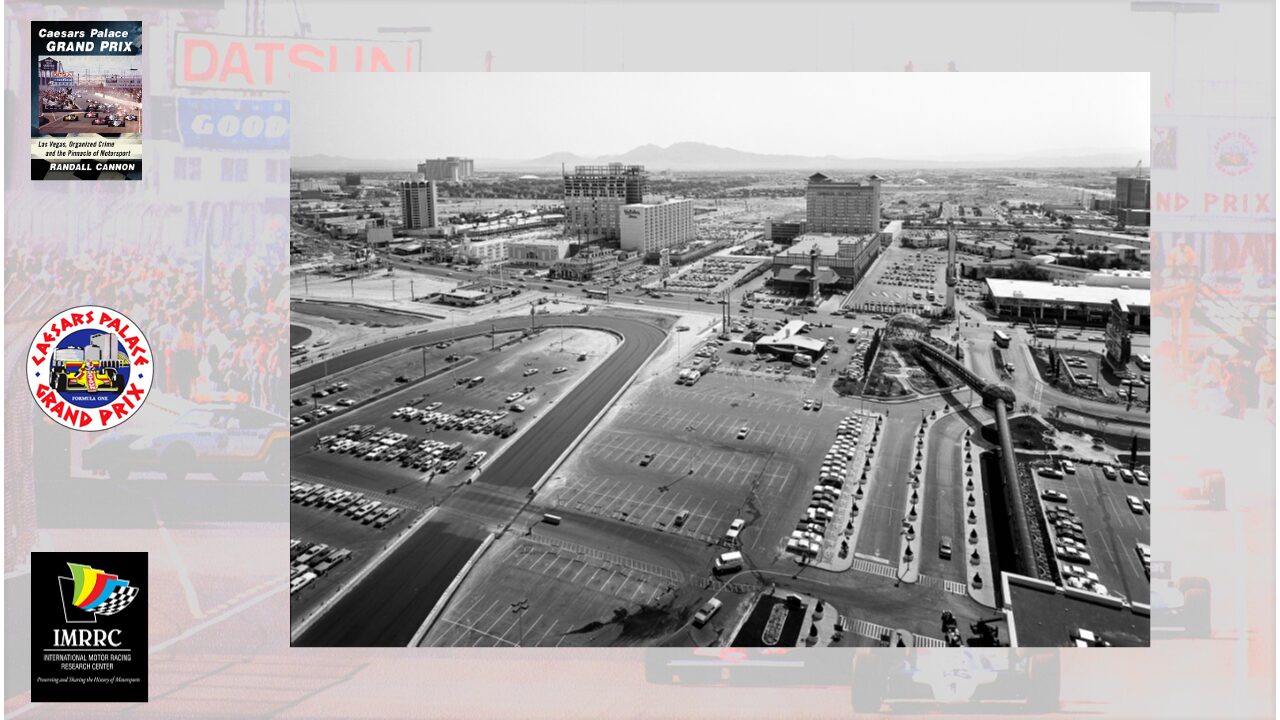

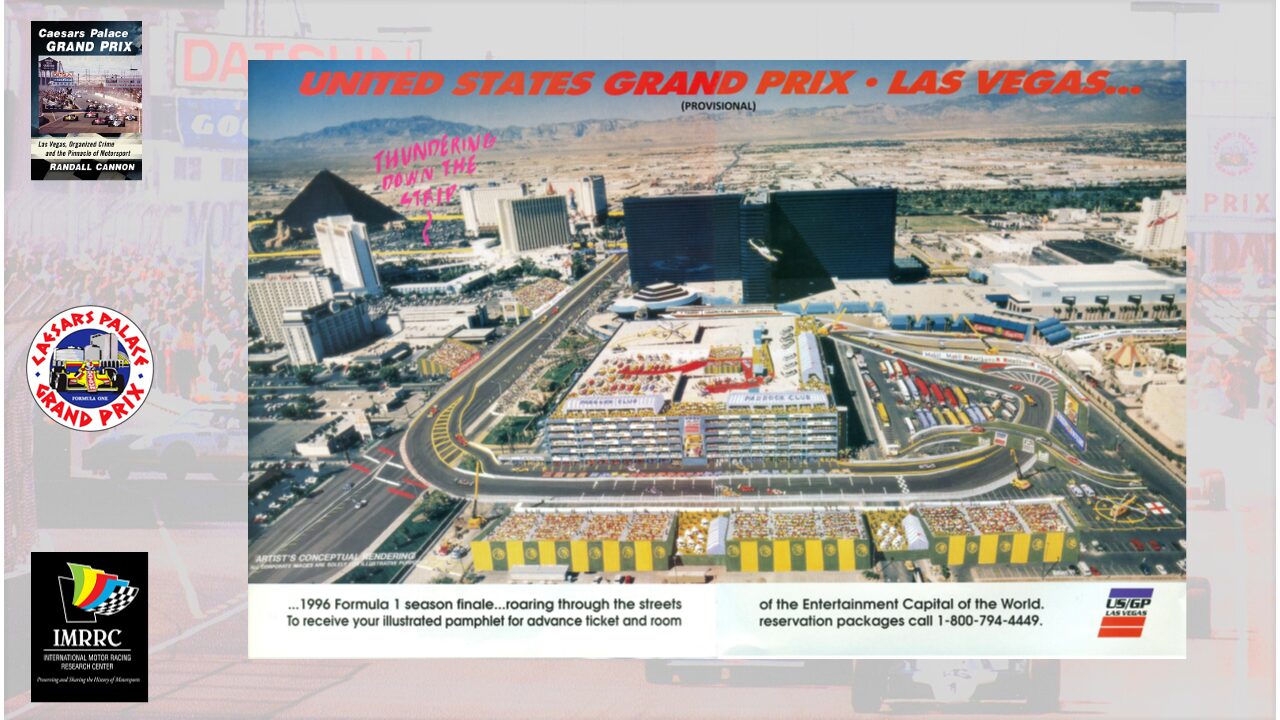

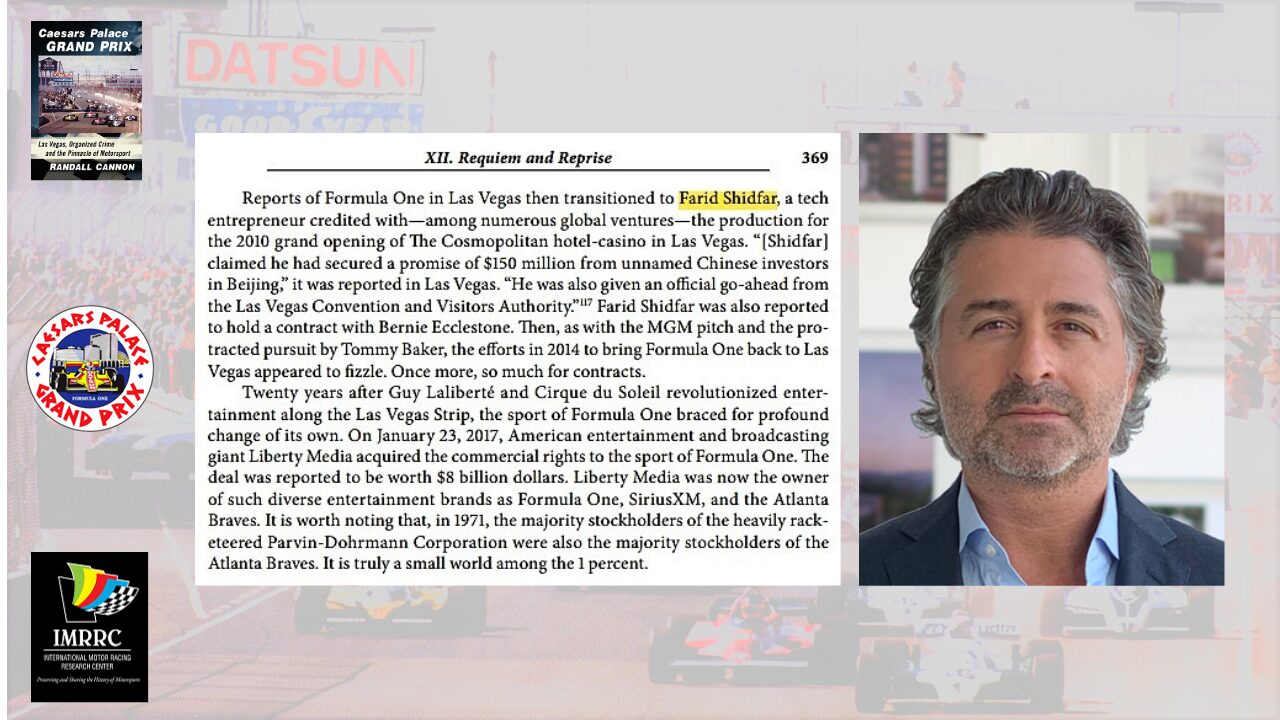

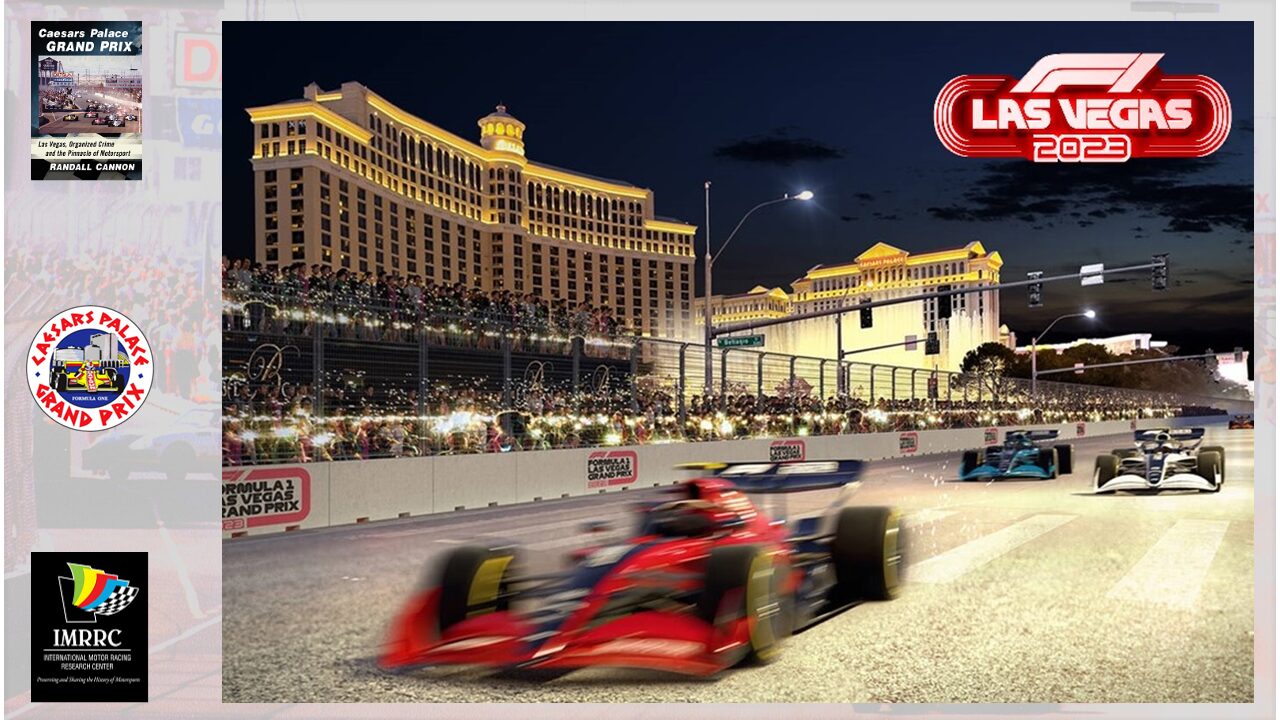

Randy Cannon’s current offering, Caesars Palace Grand Prix, drills even more deeply into that nexus while also tracing the threads of history that culminated in the only Formula One events to date in that unique city. Mr. Cannon will present at the Symposium from that research, as well as the incremental steps forward from Caesars Place that will result in the return of F1 to that destination mecca of gambling, the 2023 Las Vegas Grand Prix.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

Randy Cannon is a freelance journalist and author. His first book, Stardust International Raceway, explored the convergence of organized crime influences and motorsports interests in the international capital of legalized gambling, Las Vegas.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

This article critically evaluates the contribution of Jackie Stewart in making motor racing a safer sport for competitors. It challenges the validity of the popular assumption that Jackie Stewart by himself developed a ‘culture of safety’ that transformed the sport. Instead, the role of other individuals are identified alongside the importance of three social processes. These processes are identified as the changing balance of power between different masculine identities, the development of commercial sponsorship and a growth in the coverage of the sport on television.

The development of motor racing from the 1960s onwards as a safer sport in which to compete stems from social and cultural changes in western societies, not the isolated and independent actions of one individual. The origin story of Jackie Stewart as the originator of a culture of safety is typical of reducing a complex social process to the actions of a singular ‘prime mover’ and creates a myth that mis-represents a history of the past.

Introduction

At the beginning of the 2020 Bahrain Grand Prix Romain Grosjean had a remarkable escape from an accident which had it occurred a few years earlier would have been unsurvivable. To walk away from such an accident with relatively minor injuries was not a fortunate escape, it did not happen by chance. Instead, it can be attributed to the continuous development of regulations that are intended to minimise the risks of injury associated with accidents in motorsports. Grosjean survived not because he was lucky, but because he was the beneficiary of a process that has increasingly approached the dangers of motorsports from a rigorous risk management perspective.

This process started seriously in the 1960s and is often attributed to a pioneering campaign led by three times Formula One World Champion driver Jackie Stewart. Tremayne (1997, p. 75) for example argues that contemporary standards of safety in motor racing are a legacy of ‘Jackie Stewart’s crusading days’, whilst Hotten (1998, p. 266) observes that professional racing drivers can now be grateful to Stewart for not only improving their pay but ‘for helping them live long enough to spend it’. An article in Autosport (3rd December 1998) reflects the same opinion and states that: Fatalities were so commonplace in Formula One during the 1960s and 1970s that debates over driver safety were dismissed as a waste of energy. Then along came Jackie Stewart and the whole thing changed. Life was worth something after all. He injected ideas and standards which revolutionised the sport turning it from a risky high-speed route to the graveyard into the modern high-tech, media massaged coliseum it is today. Not completely safe, perhaps, but a lot more so.

These opinions reflect a popular assumption that the development of current safety standards stem directly from Jackie Stewart’s actions, that he is the person who started the process of making the sport safer for racing drivers. The aim of this article is not to dismiss or undermine the contribution made by Jackie Stewart, but to challenge the simplicity of assuming that he alone was responsible. Through a deeper evaluation of the past, and by situating the actions of Jackie Stewart and others into a wider social context, a different analysis will be developed. This analysis will countenance the origin story that it was Stewart who alone initiated a culture of safety which drivers like Romain Grosjean and many others have benefitted from.

A Perilous Past

Concerns about the dangers of motorsport have been ever present. The prominent Town to Town competitions established at the outset of the sport during the 1890s were stopped after several fatalities were caused by accidents during the first leg of the Paris-Madrid race in 1903. The curtailment of these races was mainly associated with the unacceptable dangers posed to spectators by racing on open public roads. Only by competing on circuits of closed roads, where the dangers to spectators could be managed more safely, could motor racing continue. When looking ahead to the forthcoming Gordon Bennett Trophy race, that was taking place in Ireland on a closed circuit of 130 miles soon after the Paris-Madrid race, The Autocar (30th May 1903) reported that: …some 7000 police officers will guard the Gordon Bennett route (and) will have strict instructions to keep people out of harm’s way; in fact, it is doubtful whether some of the spectators will get a view of the race at all. It is only a question of putting them far enough off the course for them to be perfectly safe.

The same article in The Autocar also expressed the opinion that; ‘it is idle to preach against racing, so long as it is conducted in a way that the life and limbs of the participants only are endangered. It would be a strange world in which no one was allowed to engage in a sport which was not as safe as walking in a country lane.’

This sentiment reflected a widely held belief that when accidents occurred it was spectators only, and not racing drivers, who should be protected from injury. This belief persisted from the earliest races through to the 1960s, and it is evident in a letter to The Times written by the Chairman of the Royal Automobile Club (RAC) the Earl Howe after an accident at Le Mans in 1955 when over 90 spectators were killed when a competing vehicle left the circuit and crashed into a spectator enclosure. In his letter Earl Howe wrote that; ‘drivers take the risk, must accept the risks incidental to a great contest of this sort, but if we can keep spectators from injury or worse something at any rate has been achieved.’

Similarly, the authoritative journalist Denis Jenkinson wrote in his book The Racing Driver published in 1958 that: To reach the ultimate one must ‘dice with death’ and often death claims a victim, but when he does so under such circumstances let us not bewail the fact, but rather salute and admire a man who died doing his utmost in his own specialised sphere. (p. 86)

A similar view is also expressed in the editorial of the monthly journal Motor Sport when commenting of the death of three competitors during the RAC Tourist Trophy race in September 1955. It stated that whilst sincere sympathies are offered to their bereaved parents, relations and friends they are reminded that ‘these young lives were lost in a sport calling for special qualities and the very best type of manliness on the part of participants.’

During the 1950s and into the 1960s many racing drivers competing at the top level of the sport were killed in accidents at motor racing events. Fatalities were a common occurrence, and five time Grand Prix Formula One World Champion Juan-Manuel Fangio records in his autobiography that over his 10 year career 30 of his fellow competitors were killed in motor racing accidents. Yet such a fatality rate appears to have been normalised as an accepted aspect of the sport. Apart from protecting spectators from injury there seems to have been little interest in protecting racing drivers from the dangerous risks associated with accidents.

Racing drivers were expected to courageously confront such potentially perilous risks as an integral part of a manly challenge, and even racing drivers themselves seemed uninterested in doing much to make this challenge any safer. As Tony Brooks (interview 3rd February 1997), a competitor in Grand Prix Formula One racing during the 1950s explains:

It was largely accepted as it was…I think there was the occasional circuit inspection but what was considered dangerous was probably a pointed piece of concrete about six inches from the edge of the road or something, it was very mild stuff, so there was a half-hearted effort, but it had no real clout. What then happened to make a normalised and deep-rooted belief in the risks that competitors were endangered by becoming less acceptable? Why from the 1960s onwards was there a gathering momentum to make motor racing and all

motorsports safer for competitors as well as spectators?

An era of change

To trace why a more concerted focus on protecting racing drivers from injury emerged in the 1960s, and to understand Jackie Stewart’s role, a layered documentary analysis was undertaken. This analysis was part of a broader project investigating a sociological history of safety in motorsports (Twitchen, 2004). The first layer of analysis involved researching general books on the history of motor racing alongside biographies and autobiographies of racing drivers and others involved in the sport. A further layer involved interviews with six individuals all of whom raced in Formula One racing during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. A third layer involved the systematic review of every edition of two popular English language motorsports publications, Autosport and Motor Sport, between 1965 and 1975 as this coincided with Jackie Stewart’s participation in Formula One. The final layer used the archives of The Times as a newspaper of record to cross-reference the reaction and response to important events and moments. These layers of analysis provided a mosaic of data from which the role of Jackie Stewart could then be assessed and critically evaluated. It also initially pointed to the formation of the Grand Prix Drivers Association (GPDA) as an important element in promoting better standards of safety to protect racing drivers from injury.

The formation of the Grand Prix Drivers Association

In 1961 several Grand Prix Formula One drivers met in Monte-Carlo to form the GPDA. Stirling Moss was elected chairman and Joakim (Jo) Bonnier, a Swiss driver, vice-chairman. The purpose of the GPDA was to act as a collective voice and lobby the Commission Sportif Internationale (CSI), at the time the sporting arm of the Fédération Internationale de l’ Automobile (FIA), over issues affecting the sport. One of these issues was safety and Bonnier initiated a campaign to improve safety standards at Grand Prix events. However, as Louis Stanley (1994), owner of the British Racing Motors (BRM) Grand Prix team, recalls this campaign was heavily resisted. This was because, in his view, the owners of circuits viewed the introduction of additional safety measures, for example the presence of more medically trained personal, as an unnecessary economic burden, especially if they were not required by the regulations of the CSI. This was compounded by the team’s reliance on circuit owners who often doubled as race promoters and therefore provided the teams with their main source of income. To antagonise the circuit owners by applying pressure to implement safety measures could jeopardise the amount of start and prize money the teams could expect to receive since circuit owners might justifiably point towards the extra costs incurred in meeting the demands of the GPDA. Given this dependency, and the absence of other sources of income such as commercial sponsorship, as well as disinterestedness amongst some members of the GPDA, the campaign floundered at the start and failed to initiate

any significant change. Yet the formation of the GPDA was a pivotal moment in the development of safety standards in motor racing. It may not have achieved much initially, but this was to change significantly in the space of a few years.

In 1966 Jackie Stewart crashed whilst competing in the Belgium Grand Prix at Spa in a BRM. According to his team owner Louis Stanley (letter to Autosport 24th June 1966) the response to the accident was a debacle and a complete overhaul of emergency aid provided to injured drivers was needed. Stanley suggested the creation of a system which could ensure a consistently state of the art medical response to injured drivers and in 1967 he created the Grand Prix Medical Service. (GPMS). The GPMS was an articulated truck with a specially designed trailer that contained an advanced surgical unit capable of conducting all but the most acute and specialist emergency procedures. Stanley foresaw this truck attending every Grand Prix event to reinforce and supplement the local medical facilities, and makeup for the deficiencies that were often present.

Acceptance of the GPMS was not however universal amongst circuit owners, race promoters and officials who often viewed it as an unnecessary addition to their existing medical facilities. Stanley (1994, p. 103) remembers the words of one official at Silverstone during the 1967 British Grand Prix who referred to the truck and trailer with the words that; ‘we have never had this type of vehicle before. If a driver gets injured, he will just have to take his chances like anybody else. I don’t believe in mollycoddling any fellow.’

This reaction, according to Stanley, was typical of the attitudes prevalent amongst officials at that time that were generally dismissive of attempts to raise standards of safety and emergency medical treatment. By contrast racing drivers appear to have welcomed the introduction of the GPMS. Mike Parkes, who raced for the Ferrari team, benefitted from its services following his severe accident at the 1967 Belgian Grand Prix. He wrote to Autosport (29th September 1967) how: It is deplorable to think that such a valuable piece of equipment…should have been the subject of political arguments by some race organisers who regarded it only as an insult to existing medical facilities. Any sensible person should realise that it is a valuable complement to existing facilities which could make the difference between life and death, and that it should be not be grudgingly given a site.

The introduction of the GPMS was a sign that addressing the dangers which racing drivers were exposed to was beginning to be taken more seriously by some, but not everyone. Equally it was not the only initiative being undertaken.

In 1967 the GPDA established a series of working parties to explore safety issues (Autosport 18th August 1967). One working party examined a proposal to form a professional group of marshals who would attend each Grand Prix and replace the often less effective system of part-time volunteer marshals.

Furthermore, the invention of synthetic fireproof fibres, such as Nomex that was developed by Du Pont, were also being used to make overalls for racing drivers. Pioneers here were Les Leston, a former Grand Prix driver from Britain, and Bill Simpson in North America. An Autosport editorial (21st July 1967) claimed that these fireproof suits would be an ‘invaluable investment for any racing driver, and that the CSI should give serious consideration to making their use compulsory.’

By 1967 a series of initiatives and innovations focused on either protecting racing drivers from the risks of injury caused by accidents, or better managing any injuries sustained, had been introduced. A momentum of change was being established, albeit that resistance to this change was often encountered. As Bruce McClaren (Autosport 26th May 1967) concluded: We are all doing our utmost to make the sport safer…When I first drove at Monaco I wore a short-sleeved blue sports shirt, now its fireproof Nomex underwear and overalls. Drivers didn’t wear crash helmets not long ago and when they were first suggested as a safety measure there were those who thought they were ‘sissy’.

In 1968 Dr. Michael Henderson also published his book Motor Racing in Safety: The Human Factors where in the introduction he observed that ‘the serious study of safety in motor racing is a new concept.’ In the book Henderson analysed the physics and forces involved in motor racing accidents and their impact on the human body. One significant finding concluded that in the event of an accident it was better to be restrained in a racing car by a harness (seatbelts) rather than being thrown clear. This did much to dispel the prevailing orthodoxy that remaining in a racing car during an accident was more dangerous, and consequently the finding convinced the CSI and other governing bodies to make the use of harnesses compulsory. Henderson’s book is significant for it is the first known scientifically based analysis of the dangers associated with motor racing accidents, and it is a forerunner to the contemporary approach to risk-management in motorsports as a process based on science and calculative analysis rather than subjective judgement.

In 1968 the CSI also convened a sub-committee to examine four main areas of safety. These were, circuit design, the standards of racing car design and construction, protection of racing drivers and the organisation of events. The committee would also examine the practicality of onboard fire extinguishers, the introduction of stronger ‘roll-over’ hoops and how the benefits of harnesses could be maximised. By now the momentum to better protect racing drivers was being responded to not just by motivated individuals but by the governing body as well.

The rising prominence of the GPDA

In 1969 the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa was boycotted by the GPDA because the circuit authorities had not undertaken to install crash barriers at places requested by them. The cancellation of the race because of insufficient safety preparations prompted a heated debate evidenced in the pages of both Autosport and Motor Sport. Writing in Motor Sport (May, 1969) Denis Jenkinson wrote: I have always thought that one of the enduring features of a Grand Prix driver was that he had GUTS and would accept a challenge that normal people like you and I would not be brave enough to face; now I am not so sure… If any of our so-called Grand Prix drivers would like to take-up knitting, using special needles without sharp points, I am sure I could arrange some private tuition.

Support for and against the comments expressed by Jenkinson was published in the following months edition of Motor Sport. Alan Gayfer writes for example, ‘thank heavens for Denis Jenkinson, who brings a note of sanity to the safety Grand Prix controversy’. Likewise, L.S. Coleman writes, ‘Hoo-bloody-ray! At last somebody has seen the light! Thank you for writing your courageous and naturally outspoken article…To see the TRUTH as I see it in print is worth a year’s subscription for the one issue alone.’ In contrast reader Brian Belsey wrote that he, ‘must write to express my astonishment and disgust at the views expressed by D.S.J. concerning the boycott of the Belgian Grand Prix by the GPDA.’ R.N. Tooze similarly writes, ‘I feel aggravated by the opinions expressed last month’.

In Autosport a similar range of contrasting opinions is also evident. W.B. Cope (Autosport 25th April 1969) for example expressed the view that: Racing, gentleman, came into being because motor racing provided a form of competition which meant that participants held their lives in their hands…Removing an unnecessary tree from the side of the road does not

make a circuit any less demanding, challenging or difficult. I suggest that this statement is a completely erroneous one. A tree placed on the outside of a corner…sorts out the good from the average driver. In response to this letter Neil Franklin (Autosport 2nd May 1969) writes that, ‘somebody should tell W.B. Cope that motor-racing is not about drivers gambling

with their lives.’ Whilst in another letter Terry Wright (Autosport 2nd May 1969) states that he is, ‘disgusted with Autosport for agreeing, in a recent editorial, with the aims of the GPDA over the Belgian Grand Prix.’

The influence of the GPDA and their actions in boycotting the Belgian Grand Prix over, in their view, the provision of insufficient safety standards at the circuit stirred a controversial debate. This debate oscillated between those who believed in the traditional image of the brave courageous manly racing driver who gambled with their life and an emerging belief that this was now a dated and romantic ideal.

In 1970 the switching of the German Grand Prix from the Nürburgring circuit to the Hockenheim circuit continued to inflame this debate. The switching of the 1970 German Grand Prix

The Nürburgring was considered one of the most challenging but dangerous circuits in motor racing. Since 1968, and as Jo Bonnier explained in a letter to Autosport (10th September 1970), the GPDA had been in discussions with the owners of the Nürburgring regarding the introduction of safety improvements at the circuit. Although agreeing to undertake the work by July 1970 only about a third of the work requested had been completed. The GPDA threatened to boycott the German Grand Prix and in the face of this threat the German Automobile Club, who organised the Grand Prix, switched the race to the newer and perceived to be safer Hockenheim circuit.

This move prompted Denis Jenkinson to use in his monthly column in Motor Sport to suggest that the GPDA had too much power and influence and this was being used to undermine the essence of the sport. He wrote that: I am well aware that motor-racing, or any other form of racing is dangerous, bloody dangerous, but that is what makes it exciting for spectators and competitors alike, and I know we have recently had a series of nasty accidents…but we must not get hysterical.

Support for this view was again evident in letters published by Motor Sport and Autosport. Trevor Pavitt wrote (Autosport 16th July 1970) that; ‘If Stewart and Co don’t want to drive at certain circuits, or in certain conditions, then why not let some of the brilliant crop of Formula 2 or Formula 3 drivers take their place?’ Similarly, A.R. Weller (Autosport 23rd July 1970) wrote critically of the previous week’s Autosport editorial, which had supported the switching of the race, calling it ‘childish.’ In contrast Mr. Shorrock (Autosport 23rd July 1970) expressed the opinion in his letter that, ‘can GP drivers be blamed for wanting safer cars and safer circuits?’ Similarly, and in the same edition of Autosport, Mr. Biscombe wrote to support the magazine’s view of the switch adding, ‘one hopes it may do something to nullify the Jenkinson-inspired tirade in another weekly.’

The activism of the GPDA to improve safety standards in Grand Prix Formula One racing, which would eventually filter down to all levels of motor racing, caused a heated debate and many feared the traditional values of the sport were being threatened. The nature of the debate, as expressed in Autosport and Motor Sport, can be summarised by the comments of Geoffrey Charles, the motoring correspondent of The Times who wrote that: …however well intentioned the advocates of greater safety may be, they are slowly eroding one of the basic elements and attractions of the sport for both drivers and spectators – namely the built-in danger. Give the mis-guided safety fanatics any more freedom…and every circuit will become just a harmless watered down nursery track on which only completely protected drivers will dare to race. Remove the dangers from racing and you destroy its appeal and challenge. (The Times 11th June 1968) Jackie Stewart, now a Grand Prix winning driver and leading member of the GPDA, figured prominently in these debates and as such attracted much criticism.

Fuller (1978) describes Stewart as an unloved hero and given little respect by many followers of motor racing in Britain. Likewise, Gavin (Autosport 20th July 1972) wrote of Stewart that; ‘he is an enigma, a man who contributes perhaps more than any other to the cause of motor racing yet is scorned by many of those who have the most to gain from his efforts.’ In the same article Stewart is reported as saying: The criticisms they are offering of me are abstract in most cases, its very backwards against progression. Now if I am being criticised at all for being backward in my movement, then I think it’s fair, but when I am being criticised for doing what I can to improve the sport, to make it safer and therefore a better sport, then this I think is unfair.

Autosport columnist Paddy McNally also aired his opinion following an interview with Stewart that, ‘surely for Stewart to make every possible provision for personal safety is common-sense – not being soft.’ (Autosport 9th May 1969) Such comments highlight the importance of the contribution made by Jackie Stewart, but they should not imply that Stewart was the only person taking action to make motor racing safer, that he was the lone individual. Jo Bonnier, in his capacity as vice-chairman of the GPDA, was also highly influential in galvanising the drivers’ campaign for greater safety standards. A contribution recognised by Stewart who in his own words (Autosport 20th July 1972) stated that, ‘there has never been in the history of the sport a man that has done so much to save lives as Jo Bonnier.’ The contribution of Louis Stanley should also be recognised, and as Autosport (9th August 1973) noted the GPMS which he created saved as many as 10 lives and, ‘when it comes to circuit safety and drivers lives he has attempted to do more than any individual in motor sport.’

Added to the list of influential individuals could be Michael Henderson for his inventive work on the science of safety in motorsport; Bill Simpson and the company he formed to provide safety equipment to racing drivers; and John Hugenholtz, the owner of the Zandvoort circuit in the Netherlands, who pioneered the use of crash barriers and catch-fencing. The emerging culture of safety in moto racing was the product therefore of more than one individual. It was created by individuals rather than an individual, and whilst Jackie Stewart was prominent this emerging culture should not be reduced to just his influence or actions.

Furthermore, it is insufficient to suggest that improvements to safety stem from a serendipitous collection of individual actions. What motivated these individuals to pursue their actions and enable them to overcome the resistance and criticisms they faced? Answers to this question are best understood, I would argue, by exploring the influence of three significant long-term social processes. Emerging masculinities, mediatisation and commercialisation: Their influence on safety in motorsports

In October 1964 a letter published in Motor Sport complained about the coverage given to a motor racing meeting on the BBC TV programme Wheelbase. The programme focused on an accident in which a competitor had been seriously injured and the author of letter complained that: What could have been an interesting programme was thus marred completely

and one is left to assume that the producer was bought up on one of the publications of the gutter press, concerned with providing ‘sensational’ news for the more sadistic members of the general public.

The letter is not significant so much for the words of the author, but for the fact that it is one of the first occasions when a motor racing accident is mentioned as having been seen on television. It is the beginning of a growing trend, and in the following years more correspondence and articles mention television as the media through which accidents were witnessed. For example, a letter in Autosport (19th May, 1967) begins with, ‘after having seen the fatal crash of Lorenzo Bandini on television…’, whilst the death of Roger Williamson after his car caught fire during the Dutch Grand Prix of 1973 prompts a reader of Motor Sport to write; ‘For the third time I have just witnessed on my television set the sickening spectacle of a

young man being burnt to death in a Grand Prix car.’ Commenting on the same accident the editorial of Autosport expressed the opinion that; ‘Anybody who saw the television film…will have been shocked, horrified and disgusted.’

Comments such as these are absent in the past, and two trends that gained momentum in the 1960s are evident. First motor racing events were being increasingly covered by television, and secondly television ownership was growing significantly in the more economically developed countries of the world. The consequence of these trends meant that motor racing accidents were increasingly exposed to the visible scrutiny of more people and provided them with what Peters (2001, p. 718) describes as an unparalleled sense of presence at the ‘nasty stuff of disasters’. Furthermore, television provides a visually rich form of communication which is connected to the increasingly ‘scopic regimes of modernity’ (Jay, 1992)

that have come to dominate global cultures. More extensive television coverage consequently creates the possibility of generating far more witnesses who have a relatively intimate involvement in unfolding dramas and tragedies.

The growing coverage of motorsports on television, whilst welcomed for the opportunities it provided to popularise the sport, also made the life-threatening dangers associated with accidents far more visible. Managing the balance between popularising the sport whilst not exposing it to unacceptable scenes of tragedy provided a powerful stimulus to improve the safety of the sport. The harrowing sights broadcast on television of racing drivers being trapped in burning wrecked cars for example were unacceptable and would do little to sustain the sports increasing presence as a televised form of entertainment. As Jackie Stewart (Autosport 20th July 1972) suggested after the death of Jo Siffert, who burnt to death in an accident at Brands Hatch in the UK, ‘it took a live TV camera to witness this terrible incident before people got off their arses and got something done.’

The exposure to a wider audience that television provided motor racing with, particularly for categories such as Grand Prix Formula One racing, is an important reason in explaining why the sport took the safety of racing drivers more seriously. It is also inter-related with another development namely the introduction of sponsorship from companies not directly associated with the automobile industry, an aspect of commercialism that was previously mostly only evident in North American motorsports.

Commercialisation of motorsports

There has always been a commercial element associated with motorsports. The sport was essentially born as a means for automobile manufacturers to prove the superiority of their vehicles over those of their rivals. The ‘Win on Sunday: Sell on Monday” expression has been an almost ever-present explanation for why automobile manufacturers invest in motorsports. Up until the late 1960s commercial sponsorship in Grand Prix Formula One racing was restricted to trade companies such as oil, tyre and other vehicle component suppliers. In 1968 the CSI relaxed the ban on non-trade sponsors and the Lotus team were amongst the first to take advantage by securing sponsorship from Imperial Tobacco. This arrangement saw the Lotus Formula One racing cars painted in the gold and red livery of Imperial Tobacco’s Gold Leaf brand of cigarettes and it marks the beginnings of where nontrade sponsorship flourishes in Formula One and other categories of motor racing.

The rapid growth in commercial sponsorship, whilst a welcome source of income, provided a further impetus to improve the safety of the sport. Tobacco companies were particularly attracted to the sport as they had been banned in many countries from advertising on television and given the growing presence of motor racing on television the sponsorship of a team was an effective way of circumventing this ban. However, the growth of commercial sponsorship might be jeopardised if serious and fatal accidents remained commonplace and subsequently generated negative press coverage. As Paddy McNally wrote in his weekly Autosport (11th June 1970) column; ‘Modern motor racing depends very much on sponsorship, but major companies are going to think twice if there is ever the sort of national catastrophe which would occur if a Formula One car left the circuit and went into the crowd at 180mph.’

The growing coverage of motor racing on television and the increasing sponsorship of teams by a range of organisations other than those associated with the motor trade is an example of the sponsorship-advertising-media axis (Hargreaves, 1986) which has been a significant development in sport since the second half of the twentieth century. In motorsports this axis has had the unintentional consequence of providing an additional layer of momentum towards making the sport safer for racing drivers. As motor racing has incorporated the

sophisticated advertising and marketing methods (Wernick, 1991) of consumer culture (Baudrillard, 1998), in which racing cars and drivers have become 200mph billboards (Yost, 2007), so the sport has had to protect itself from forms of negative publicity that might discourage sponsors from investing their money. As a former Grand Prix driver commented when reflecting on the fatal accident to Ayrton Senna in 1994, ‘Senna’s death happened in front of 350 million viewers and that as a PR exercise was pretty damming and it must never be allowed to happen again.’

Together then with the increasing visibility of motor racing on television, coupled with the development of commercial sponsorship, it is possible to see how the circumstances of the time were becoming amenable to the introduction of more stringent safety standards that would better protect racing drivers from injury and death. However, the shifting balance of power between different masculinities is a further social process that has further contributed to this development.

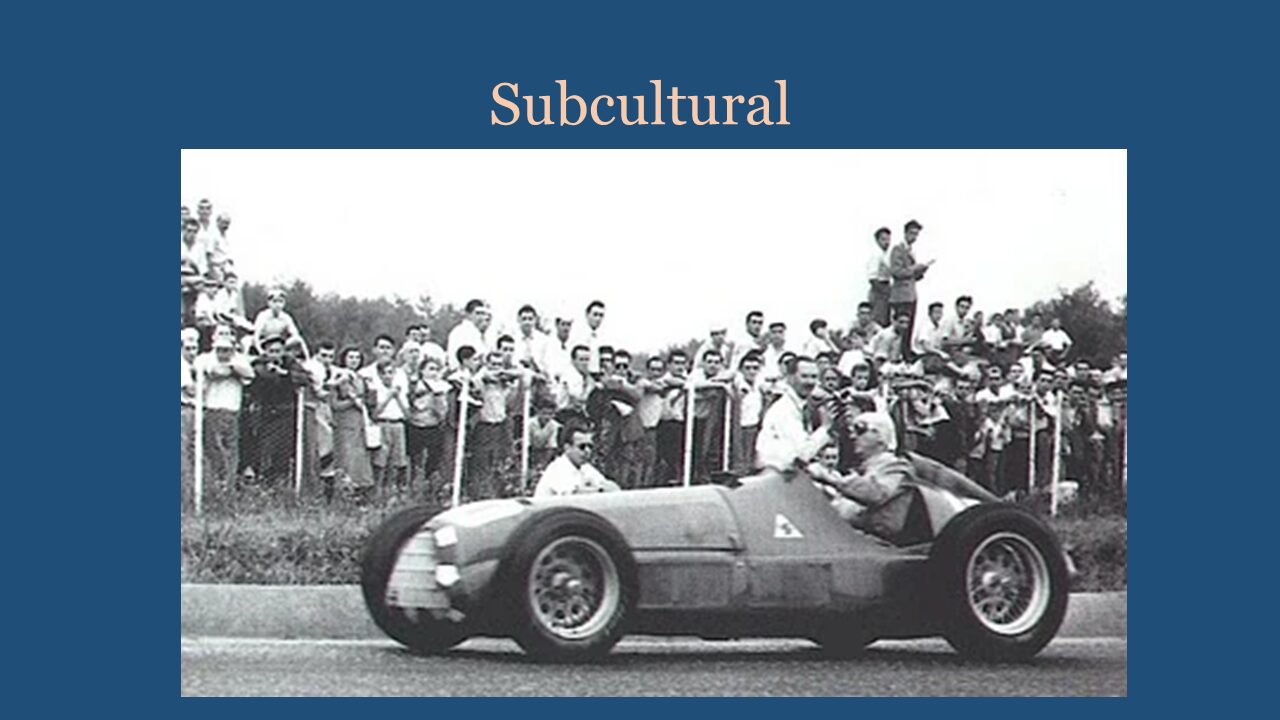

Motorsports, masculinities and the male preserve Motorsport is a ‘male preserve’ (Dunning, 1986), a social space dominated by men. Only in recent years has the growing presence of more female competitors addressed this gendered power imbalance (Matthews & Pike, 2016). Motor racing is also a social space that has traditionally been dominated by a particular form of masculinity. The traditional masculine image of the racing driver prevalent throughout much of the history of the sport is symbolised by one that is courageous, rugged, fearless and heroic in the face of mortal danger. It is a masculine identity that Mangan (1995) refers to as ‘muscular, militaristic and manly’ and associated with the noble virtues of military service. Edwards (1997) captures this when he describes racing drivers in the 1950s as being the ‘spiritual successors’ to the Royal Air Force pilots of the Second World War.

By the 1960s this dominant masculine identity was being challenged by a different masculine identity, a masculinity more associated with style and consumerism. Within sport, and especially motor racing, the balance of power between different masculinities was changing. Manliness was becoming more fluid and complex and no longer encoded within the narrower confines of a militaristically influenced masculinity. The effect of this meant that the narrative of serious and fatal accidents in motor racing was less likely to be justified or

explained through the virtues of a heroic masculinity. The death of a racing driver, as the inevitable consequence of a dangerous sport participated in by fearless individuals who ‘diced with death’, was becoming less acceptable and less legitimate. Yet this was not a sudden transformative process, instead it was an emerging longer term social process that was to have a growing impact on the motivation to make motor racing a safer sport. This is captured by former Formula One World Champion Jacques Villeneuve, whose own father Gilles was killed in an accident at the Belgian Grand Prix in 1982, when he suggested in Autosport (27th April 1997) that, ‘twenty years ago racing drivers were presented as being different

and special now we are just assumed to be like normal athletes.’

In stating this observation Villeneuve is highlighting the significant shifts in the balance of power between different masculinities that have taken place and witnessed in motor racing. Differences that have undermined fatal accidents in motor racing as the normal consequence of a dangerous sport in which special men with gallant and adventurous virtues compete against each other. I have therefore presented here three social processes that converged significantly in the 1960s to inform the beliefs, decisions and actions of individuals. These processes undermined the opinions of those who believed racing drivers were a special breed of men, and that fatal accidents were the inevitable occurrence of a dangerous sport of which little could or should be done to prevent. Instead, the social processes outlined provided a powerful stimulus to support those attempting to make the sport safer. By explaining the relationship between the actions of individuals and the changing social circumstances of the time it is possible to better understand how making motor racing a safer sport for racing drivers was a process of decisions and actions taken by individuals situated in the context of changing societies.

Conclusions

In June 2000 the FIA launched a policy document called Formula Zero. This policy sought to transfer the approach undertaken in motorsports towards safety improvements and apply it to the public highways. The document also states that although ‘motorsport is inherently dangerous and that accidents will inevitably happen the fundamental starting point for the FIA’s safety philosophy is the principle that no deaths or injuries on the track are acceptable.’. This principle is a significant shift in the beliefs and approach evidenced in the past. The document also observes that this shift has witnessed responsibility for safety moving from the racing driver to the administration and system suppliers. Yet since 2000 fatal accidents involving competitors, spectators and officials have occurred, albeit with nowhere near the frequency and sense of inevitable expectation as before. This transformation in the normality of fatal injury, and the subsequent actions to improve the safety of racing drivers, cannot be seen as originating from the influence of Jackie Stewart alone. Stewart had an important role, and he should be recognised for his contribution, but many others should also be recognised for their contribution as well. The populist explanation that it was Jackie Stewart who initiated the safety culture in motor racing therefore typifies the type of monocausal explanation that reduces a complex social process to the actions of a primemover (Maguire, 1988).

This article has sort to address this complex social process and explain how the motivation of individuals to improve the safety of racing drivers from the 1960s onwards can be better understood when situated in a wider context. The growing commercialisation of motor racing the increasing coverage of the sport on television and the shifting balance of power between different masculinities are just three important social processes that have converged to render the previous almost normal and acceptable level of fatal accidents involving racing drivers unacceptable. As Watkins (1996) has argued the ‘sociological changes’ widely occurring in western societies has made the old panache of motorsports no longer acceptable. In this article these sociological changes have been described and explained to provide a more detailed and evidence informed history of the past.

Furthermore, by doing so the task of sociologists and social-historians to be, as Elias (van Krieken, 1998) argues, the destroyer of myths has been at the forefront of the evaluation process. In undertaking this task the origin story of Jackie Stewart’s role in making motor racing a safer sport has been critically challenged and shown for the reductive and simplistic explanation that it conveys.

References

- Baudrillard, J., 1998. Consumer Society. London: Sage.

- Dunning, E., 1986. Sport as a Male Preserve: Notes on the Social Sources of Masculine Identity and its Transformations. In: Quest for Excitement: Sport and Leisure in the Civilizing Process. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 267-283.

- Edwards, R., 1997. Managing a Legend. Sparkford: Haynes.

- Fuller, P., 1978. The Champions: The Secret Motive in Games and Sport. London: Allan Lane.

- Hargreaves, J., 1986. Sport, Power and Culture. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Henderson, M., 1968. Motor Racing in Safety: The Human Fcators. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens.

- Hotten, R., 1998. Formula 1: The business of winning. London: Orian Business.

- Jay, M., 1992. Scopic regimes of modernity. In: Modernity and Identity. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 178-195.

- Jenkinson, D., 1958. The Racing Driver. London: B.T. Basford.

- Maguire, J., 1988. Doing figurational sociology: Some prelimanary observations on methodological issues and sensitizing concepts. Leisure Studies, pp. 187-193.

- Mangan, J., 1995. Duty until death: English Masculinity and miltariusm in the age of new imperialism. Interantional journal of the history of sport, pp. 10-37.

- Matthews, J. a. P. E., 2016. ‘What on Earth are they doing in a racing-car?’: Towards an Understanding of Women in Motorsport. The International Journal of the History of Sport, pp. 1532-1550.

- Twitchen: Stewart’s Crusade: Unpicking a Myth Published by University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository, Peters, J., 2001. Witnessing. Media, Culture and Society, pp. 707-723.

- Stanley, L., 1994. Grand Prix:The Legendary Years. Harpenden: Queen Anne.

- Tremayne, D., 1997. The Science of Speed. Sparkford: Haynes.

- Twitchen, A., 2004. The body, sport and risk: A historical sociological of motorracing.Unpublished PhD thesis van Krieken, R., 1998. Norbert Elias. London: Routledge.

- Watkins, S., 1996. Beyond the limit. London: Macmillan.

- Wernick, A., 1991. Promotional Culture: Advertising, Ideology and Symbolic Expression. London: Sage.

- Yost, M., 2007. The 200mph Billboard. St. Paul: Motorbooks

Twitchen, Alex (2023) “The Crusading Days of Jackie Stewart: Evaluating the Development of Safety in Motor Racing During the 1960s.,” Journal of Motorsport Culture & History: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: https://scholars.unh.edu/jmotorsportculturehistory/vol3/iss1/4

This article is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Motorsport Culture & History by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository. For more information, please contact Scholarly.Communication@unh.edu.

About the Journal of Motorsports Culture & History

The Journal of Motorsport Culture & History aims to provide quality motorsport based academic research based on cultural or historical inquiries. Issues will be released once per year in the fall, starting in October of 2019. Manuscripts will be subject to a desk review for fit, and a double-blind peer review for quality and rigor. Student authors are encouraged to submit their research. The scope of JMCH includes, but is not limited to, motorsport research or interpretive essays within: sociology, cultural studies, communication studies, and history (books & newspapers, films, movies, radio & television, museum exhibits, resource guides).

Has Formula One left behind its gritty, dangerous and somewhat esoteric past to become a cross between the World Cup and Disneyland? How much of its new global popularity can summed up as (perhaps merely) “media spectacle?”

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Bio

James Miller’s engagement with Formula 1 includes chatting about race strategy with Nikki Lauda at the 1977 US Grand Prix, where Lauda won his second world championship. Now it involves at-home viewing of real-time, in-car camera images on a flat screen TV.

Dr. Miller is professor emeritus of communications at Hampshire College. He has studied new media as a Fulbright researcher in Paris and a visiting professor at MIT’s Media Lab.

Slides

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides as you follow along with the episode.

Livestream

Other episodes you might enjoy

The first purpose-built, closed-course, road circuit at Watkins Glen, opened on a glorious, chilly autumn weekend in mid-September 1956, welcoming 118 racers to compete in six race events during the 9th Annual International Sports Car Grand Prix. The circuit, which has since hosted nearly every major racing series over more than six decades, almost did not open at all.

The efforts by the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation – up to the 11th hour – to ready the 2.3-mile track in time for the race weekend were extraordinary. A successful “wave the green fag” bond campaign in the local community raised initial start-up funds for the project in a single month. Contractors broke ground in late July and, after delays caused by heavy rains and unfavorable weather, completed the final touches on the asphalt paving only an hour before practice sessions began. Alterations to one of the curves, using earth-moving equipment under the glare of spotlights, were made during the night before the first race. And then officials from the Sports Car Club of America jeopardized the entre event by withdrawing their recommendation for members to participate at the last minute due to what they deemed the “serious and hazardous conditions of the course.”

Despite official concerns, not a single driver willingly withdrew from competition. A crowd exceeding 30,000 spectators enjoyed the “European carnival aspects” of the weekend and watched a “thrilling race” across the fast and tricky course as George Constantine of Sturbridge, Massachusetts in his D-Type Jaguar took the checkered fag for the Sports Car Grand Prix.

The IMRRC

With a mission to “To collect, preserve and share the global history of motorsports,” The International Motor Racing Research Center, located at Watkin’s Glen, New York, has, since 1996, been a place open to historians and to the general public and preserves an ever-growing collection that documents the history of racing in the more than 4000 books, 250 different motorsports magazines and newspaper titles, club and sanctioning body records, race results, programs and posters, papers of motorsports journalists and scholars, correspondence of race organizers and still and moving images. Its knowledgeable research and archives staff assists hundreds of scholars, journalists, authors, documentary film makers, drivers and race car owners from all over the globe with inquiries about motorsports history every year. It relies on gifs and donations from the motor sport community. See www.racingarchives.org.

Download the Original Article.

Founded in memory of David Chandler of Olive Bridge, NY, this Memorial Fund is the perfect way to honor a friend or loved one’s memory while celebrating their enthusiasm for Formula One.

Founded in memory of David Chandler of Olive Bridge, NY, this Memorial Fund is the perfect way to honor a friend or loved one’s memory while celebrating their enthusiasm for Formula One.

David’s friend, Stewart Long, wrote a letter in his memory for the start of the fund:

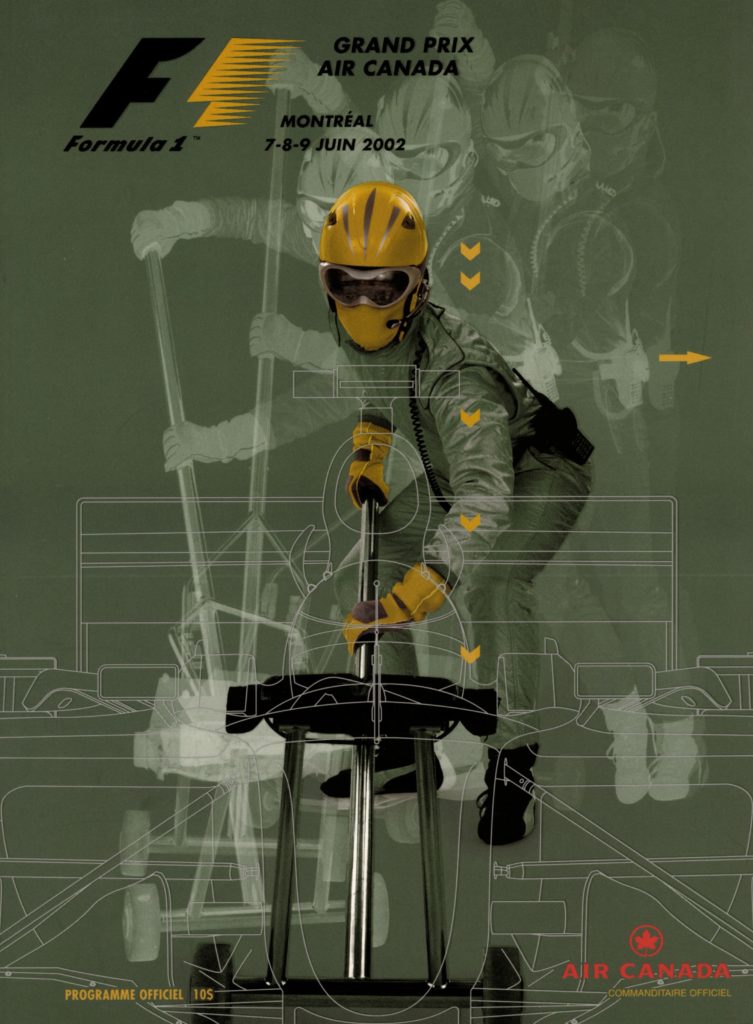

“Dave and I attended about 10 Formula One Grand Prix races in Montreal from the early 1990s through the mid-2000s, during which time we became fast friends by sharing our interests as Formula One fans.

We would arrive at Circuit Gilles-Villeneuve as soon as the gates opened, stay all day, and be among the last to leave. We saw everything: the mechanics opening the garage doors and warming up the cars, working on the cars, the cars on the track. We spotted drivers, team managers, and celebrities in the pits. We were there the first year Michael Andretti was in Formula One and put up a banner in the stands that said, ‘USA Supports Andretti.’ It was reported on by one of the French newspapers, so we shared our 15 minutes of fame together.

Dave was a pure and passionate enthusiast. He was a huge fan of Ayrton Senna, the brilliant driver from Brazil with exquisite car control skills and a three-time world champion. He even had a Senna tee shirt with the famous and stylistic Senna ‘S’ on it. One year, as usual, I waited outside the pits (after Dave had left since he had to drive back that evening to go to work on Monday) to see the drivers as they left. To my great pleasure, Senna came by and stopped to sign autographs. I was in a line of about eight people and thought, ‘Wow, I’m going to be able to get my program signed by Dave’s ultimate driver, and won’t he be thrilled when I send that to him.’ Unfortunately, Senna waved and moved on when I was only two people away from him. So close. Still, Dave and I shared that story many times so it had positive benefits in that regard.

Dave was a great friend and racing enthusiast. He will be deeply missed by his family, colleagues, and friends. His spirit as a Formula One fan will live on in this Memorial Fund.”

To read the complete letter, click here.

Make a contribution to the Formula One Fan Memorial Fund. Leave a note in the description box that says Formula One Memorial Fund, and the name of who you’d like to honor. You can also send a check made out to IMRRC at 610 South Decatur Street, Watkins Glen, NY, 14891.