The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Standing at just 5 feet, 6 inches tall, Charlie Rainville’s small stature didn’t seem at first glance to be a good fit in the high stakes, high-pressure world of big-time sports car racing. But competitors and manufacturers that underestimated him quickly learned the hard way that Charlie was not a man to be trifled with. He was tough as nails, a kid that grew up on the wrong side of the tracks in Providence, Rhode Island. He was street smart, savvy and ready for a fight. But he was also immensely clear thinking and eminently practical when it came to managing the many conflicting personalities that were each vying for an unfair advantage. The ever-present twinkle in his blue eyes and ready smile were Rainville’s main weapons for disarming tense situations, but he also commanded immense respect from competitors familiar with his experience.

One of the original pioneers of U.S. road racing, Charlie had earned a reputation as a tough competitor and brilliant race car preparer, starting as a mechanic at Jake Kaplan’s Import Motors shops in Providence in the late 1950s. Known for being able to massage anything to go faster than originally intended, he was the go-to guy for preparing sports cars in New England for the growing groups of enthusiasts importing them from Europe. Charlie became an expert on all of the exotic cars of the day, including Alfa Romeo, Jaguar, Lotus, Ferrari, Porsche, OSCA, Iso Grifo, Datsun, and Corvette. In addition to engines and suspension setup, he became a true artist, hand forming aluminum body panels for all sorts of makes and models.

An accomplished racer, Charlie Rainville drove for the factory Plymouth Trans-Am team in 1966, including the opening round at Sebring, where the Trans-Am cars had a four-hour race ahead of the 12 Hour classic. Photo: REVS Institute

As a driver, Rainville had a brief career in sprint cars and on short tracks until he gravitated to SCCA track events, hill climbs and rallying in the New England area, campaigning in aluminum- bodied XK120 Jaguars, Alfas, OSCAs, and Cobras. He then jumped to the professional ranks by competing in SCCA Trans-Am series events in Barracudas as part of the first works team from Detroit in 1966. A few podiums and a fifth-place overall finish in the points that first year of the Trans-Am would mark the pinnacle of his driving career. Along the way, Charlie built a reputation for helping anyone in the paddock with parts, labor, and advice, and then going out and beating them on the track.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Don’t Lean Too Hard on the Doors

The cars for the first-ever Trans-Am race were run as a separate class at the Sebring 12 Hour in 1966. As both John Bishop and Charlie Rainville relayed it, they met on the grid just before the race. John went over to the driver’s side of Charlie’s car to wish him good luck in the race. As he leaned in on the door to talk, the door started collapsing. John knew that the SCCA had approved alternative thin steel door panels for the Plymouth, but he was unprepared for how thin! Charlie laughed and promptly pounded the panel back out with his fists from inside the car and made no reference to the fact the door was, in fact, aluminum which, needless to say, was not a standard Barracuda part in 1966. John gave his apologies for damaging the car, along with a wry smile and walked away. Charlie went on to finish seventh that day.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By the end of the 1960s, Rainville had retired from racing and evolved into one of the top SCCA race stewards in the country. He and Bishop had crossed paths many times by this point. Bishop saw that Rainville’s view of how racing should be conducted matched his own and when the opportunity came to forge a partnership of philosophies, he became the obvious choice to lead the charge for IMSA at the track when it came to technical and competition matters.

The man who made the tagline “Racing with a Difference” come to life at IMSA events for many of the participants was Rainville. He was IMSA’s chief steward, race director, technical director and director of competition from IMSA’s start through the early 1980s. In appointing him to these positions, Bishop understood that Rainville brought decades of useful experience in car construction, race preparation, competition driving and race officiating to the table. He knew instinctively that Charlie would command immediate respect from competitors, team owners, race organizers and manufacturers.

The solid partnership forged between Charlie Rainville and John Bishop made IMSA tick for many years. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Rainville’s no-nonsense, common sense approach to technical rules, race regulations and race management confirmed he was the logical choice to run the competition side of the new organization. He introduced a new style of series management: benevolent dictatorship, something competitors had not experienced in the highly political world of the SCCA.

Hurley Haywood had this to say about Rainville: “He would look at the situation and say, “That’s a good idea,” or “No, that’s not a good idea.” There was no discussion. Whatever he said was final. You could talk until you were blue in the face, and you weren’t going to change his mind. Most of the time, he was pretty reasonable. John softened these situations by playing the ultimate diplomat. John would never put his foot down and say “This is the way it’s going to be. You’re going to do it my way or hit the bricks.” John always left the door open where you could see some light shining through. There was always hope.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: The Chopped Camaro

One story that illustrated Charlie Rainville’s practical approach to policing rules happened at Laguna Seca in 1976. Carl Shafer, a regular on the IMSA circuit in his orange Camaro, had towed all the way to California along with a bunch of other East Coast competitors. At the time, IMSA was still building a foothold with the West Coast races and needed every entry it could get. As the Camel GT cars were sitting in pit lane, waiting for practice to begin, Charlie stood next to Shafer’s Camaro, just staring at it long and hard; something just didn’t look right. Charlie called Shafer over and the two of them faced each other. Shafer was 6 foot, 3 inches tall, so he towered over Charlie, who asked him: “The car doesn’t look right, Carl. Did you chop it?” Shafer, knowing he had been caught, looked down and replied in his slow Midwestern drawl: “Yeah Charlie, I did.” Turns out the car’s roofline was four inches too short from the standard Camaro template. But rather than throw him out and not let him race, Charlie told him to weld a four-inch spoiler to the top of his roofline, which the team did that night. It looked like hell and acted as a boat anchor at speed, but at least he didn’t have to tow home to Wyoming, Ill. without racing and IMSA had another car in the field.

Michael Keyser leads the first lap of the Camel GT Challenge race at Laguna Seca in 1976. Al Holbert, Peter Gregg, and Carl Shafer follow. A four-inch spoiler is visible on Shafer’s Camaro, mandated by Charlie Rainville after IMSA found that the roofline had been chopped. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Passing Tech Inspection

Jim Busby recalled: “Charlie’s policing was fascinating to me. We’d be doing something really bad, so far out of the box that it was ridiculous. One example was when we modified the wheelbase of a Porsche Carrera RSR to take the weight off the rear end. Having the weight there was great, for the first half of a stint, but we burned off the rears after that. We had to find a way to move weight forward.”

“Right before Mid-Ohio one year, I got to thinking. What if we just move the holes in the fenders forward like three or four inches and move the engine forward three or four inches and misalign the half shafts forward three and a half inches? We made Porsche A-arms that looked stock but moved the wheelbase forward, which shifted the engine and transmission weight forward and shortened the rod that went from the shifter to the transmission and off we went. We took the car to Mid-Ohio and were getting ready to race, but first, we had to get the car through inspection.”

“We’re standing there in the tech shed and Charlie was standing there looking at the car, then looking at me. Over and over again. Back and forth between the car and me, like he was asking with his eyes: “You’re up to something, I just don’t know what it is yet.” Finally, I turned around and I looked at him and he looked at me and he had a look in his eye like, “Is there something you want to tell me?” I responded: “Oh hey, Charlie! How are you?” He nodded his head and walked away. John did that to me a lot too. His patience for me would really grow thin.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Charlie’s stature within the SCCA was solid and influential, particularly the corner workers and other officials. He felt most at home with the hundreds of volunteer officials and course marshals that showed up every race weekend. This allowed him to diffuse some of the early politics that the SCCA had with IMSA. The workers respected him and loved working with him at the track. He quickly added a number of key SCCA stewards, notably, Roger Eandi in California, K.C. Van Niman in the Midwest and Charlie Earwood in the Southeast into IMSA’s fold as race officials. They remained a significant part of the organization for the balance of their careers well into the 1990s.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR: Shicklegruber Fuel Injection

Mark Raffauf remembers a classic Charlie Rainville story: “Charlie worked in the IMSA office in Connecticut a few days a week when there wasn’t a race meeting to attend. Although he was an integral part of the behind-the-scenes rules process, Charlie wasn’t really at home working in an office. He preferred the smells, the grime and the comradery of the track or garage. We were working on finalizing the rule book for the 1977 season when one day, Charlie walked into my office and asked: “What’s the name of the fuel injection that BMW wants us to allow for the 320i?” Both Roger Bailey and I answered: “Kuglefischer.” Charlie thanked us and went back to his office. A month later, after we published the rule book, we received a frantic call from Jim Patterson, who ran BMW’s racing program in North America at the time. Apparently, Charlie had published the rule book with the name of the approved BMW fuel injection as “Shicklegruber,” which is how Charlie apparently translated “Kuglefischer.” We never lived it down with the BMW folks.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

John Bishop and Rainville together forged a philosophy and organization that set new standards of professionalism, communication and empathy that were soon copied everywhere. Although emotions often ran high, drivers respected the decision-making process and often would admit that it was fair, even if it went against their position. Charlie looked out for the competitors in ways very different from previous attitudes about the relationship between officials and participants. They were his drivers and he went to great lengths to take good care of them. And he started every day with a clean sheet of paper, nothing from the previous day was held over anyone.

Charlie Rainville and John Bishop in 1979. Photo: IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

The staff that worked for IMSA were mentored and taught how to do the right thing, how to be straight-forward and how not to be afraid of making decisions or the resulting consequences. Sure, mistakes were made, but Rainville was generous and forgiving the first time. The second time was not so pretty. From this process, a new generation of professionally trained, full-time officials was developed who eventually held the reins well into the 1990s. Because of this training, when Charlie retired in 1983, the transition to Mark Raffauf was virtually seamless. Though still attending the races for another year he never injected himself into the activity unless asked, but he was always there for support if needed.

When Rainville passed away in February of 1985, sports car racing lost one of its true pioneers. At the time, Ken Parker of the Providence Journal-Bulletin wrote; “No man is irreplaceable, but one cannot help but feel a twinge of sympathy for the person who steps into Charlie Rainville’s shoes. During his many years as Racing (and Technical) Director of IMSA, Charlie was known, loved and respected nationwide, not only for his competence but also his fairness and quiet generosity. John Bishop, President of IMSA, gives Charlie much of the credit for making IMSA the world’s foremost professional racing organization, and Charlie raised IMSA to that level in less than 10 years.”

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

BMW of North America’s racing group was established in 1975 in an effort to support the company’s growth in the lucrative US performance car market. Unfortunately, the company did not have an IMSA championship to show for the investments in the BMW 3.0 CSL and the turbocharged BMW 320i. With just one or two cars pitted against a host of Porsches, the odds were not in their favor. The tube frame M-1 Procar did crush the GTO competition in 1981 but was underpowered in IMSA’s top GT Prototype (GTP) class.

Something had to be done to narrow the gap. Former SCCA executive Jim Patterson, who took over the BMW North America racing program in 1978, saw the newly minted IMSA GTP rules in 1980 as a way to get back in the game. Working with partner March Engineering, a unique new prototype was unveiled in early 1981 that would become the basis for a long, successful supply of GTP cars to the IMSA field from the British company.

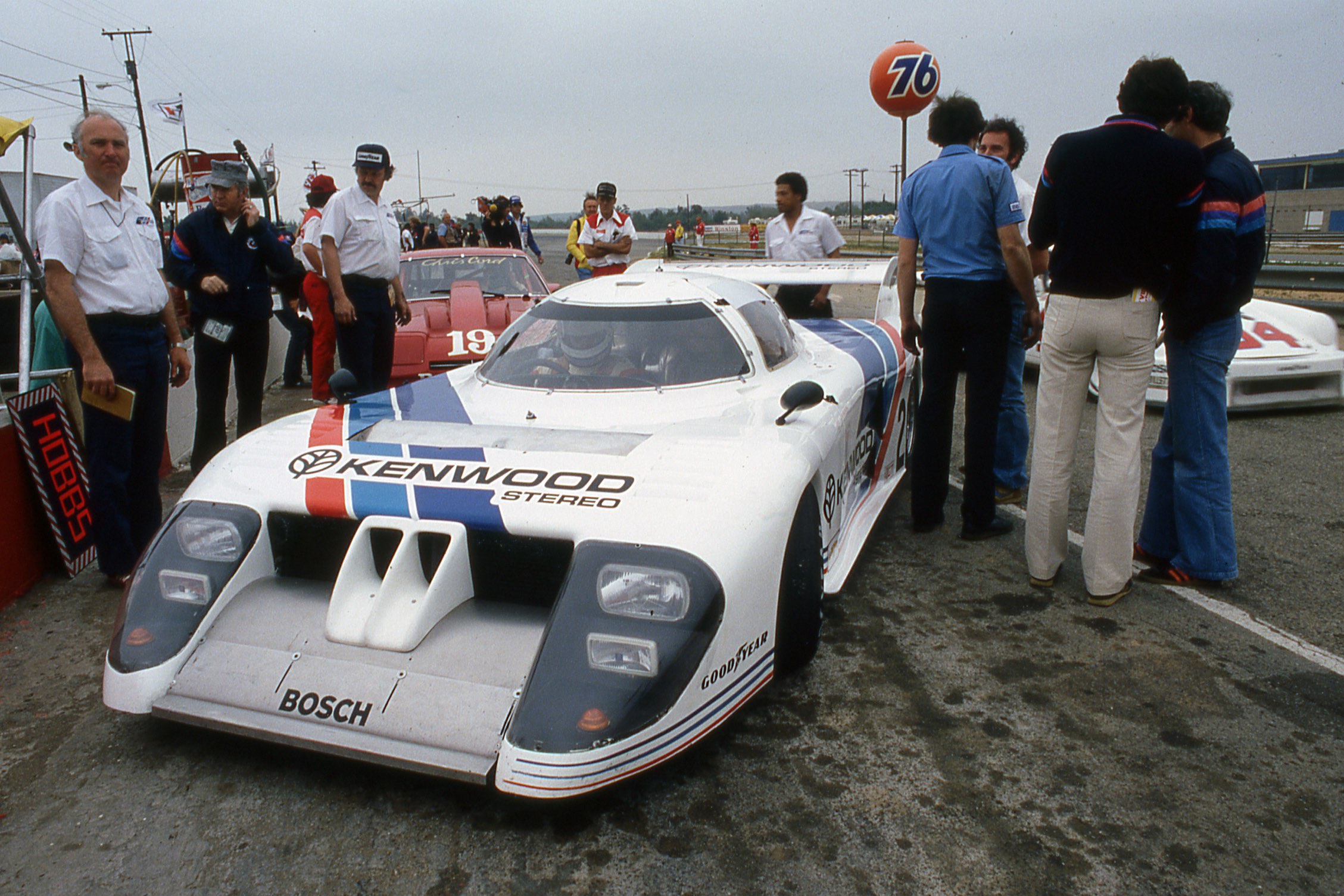

The BMW M1/C debuted at Riverside in April 1981. The March chassis featured a modern aluminum monocoque that was mated to a normally aspirated 3.5-liter BMW engine. The team would upgrade to a 2.0-liter turbocharged motor later in the year. Photo: Don Hodgdon

Designed by French aerodynamics expert Max Sardou and BMW engineer Raine Bratenstein, the car was dubbed the BMW M-1/C. It was built around a March Engineering aluminum monocoque and featured two distinctive pontoons at the front that were designed to channel airflow to both the radiators and twin ground-effects tunnels for maximum downforce. The car was initially fitted with a 3.5-liter, six-cylinder, normally aspirated BMW engine, and entered for the first time at the Riverside 6 Hours in April 1981 with David Hobbs and European endurance veteran Marc Surer at the wheel. Featuring sponsorship livery from Kenwood audio, the pair finished a credible sixth place, albeit eleven laps down to the winning 935 piloted by Fitzpatrick and Busby.

The lone BMW M1/C is swamped by a host of Porsche 935s at the start of the 1981 Riverside Camel GT race. The M1/C would go on to finish sixth, eleven laps down from the winning Porsche 935 of John Fitzpatrick/Jim Busby (#1). Photo: Don Hodgdon

A week later at Laguna Seca, Hobbs placed sixth again, this time one lap down to the new Lola T-600 with Brian Redman at the wheel. Although down on power, Hobbs managed to put the car on the front row at both Lime Rock and Mid-Ohio. The first few races proved the M-1/C had real potential and the decision was made to further develop the chassis and engine. The long-term plan was to install the 1.5-liter turbocharged BMW motor being developed for Formula One, but that engine wasn’t ready and would never be used in the March. Instead, the team force-fit the same turbocharged 2.0-liter, four-cylinder engine that had been used successfully in the McLaren-engineered BMW 320i program. Since the M-1/C had not been designed for that power plant, it required a cooling workaround for a motor that produced 600 to 675bhp with the boost turned up.

Results were mixed after the change. The new engine debuted at Sears Point in August. The car was fast and competitive, but ultimately unreliable. A fourth place at Portland would turn out to be the team’s best finish. Despite stating long-term commitments early on, BMW again left IMSA racing at the end of the year, this time to focus on its Formula One program.

Even with this setback, March Engineering took what it had learned from the M-1/C experience and produced a viable, stable GTP customer car for 1982, dubbed the 82G, that was designed by Gordon Coppuck. The first two customer March 82Gs appeared in January for the 24 Hours of Daytona. One of them was a Chevrolet V8-powered version driven by Bobby Rahal and Jim Trueman and fielded by Garretson Enterprises. Rahal would campaign the car in later rounds with Michelob backing.

The first March 82G customer car was fielded by the Garretson team at Daytona in January 1982. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

The other March was campaigned by Dave Cowart and Kenper Miller’s Red Lobster team. After winning the 1981 GTO championship in the dominant BMW M-1, the team commissioned an 82G from the March factory with the now well-tested 3.5-liter BMW M-1 engine. The distinctive twin pontoons of the March turned out to be a perfect canvas for two Red Lobster claws, a design that became iconic almost instantly. Unfortunately, the normally aspirated BMW engine was no match for the Chevy V8 or Porsche 935s, and for 1983 the team campaigned with Porsche 935 turbo power, only to suffer from overheating issues. The team took the midsummer Daytona race off in 1983 and came back later in the year with Holbert’s second March 83G powered by a Chevy V8.

The twin pontoons of the March 82/3G were ideally suited for the paint scheme of the Red Lobster team, pictured here in 1983 at Daytona, leading the similar Porsche-powered March of Al Holbert. Photo: Richard Bryant

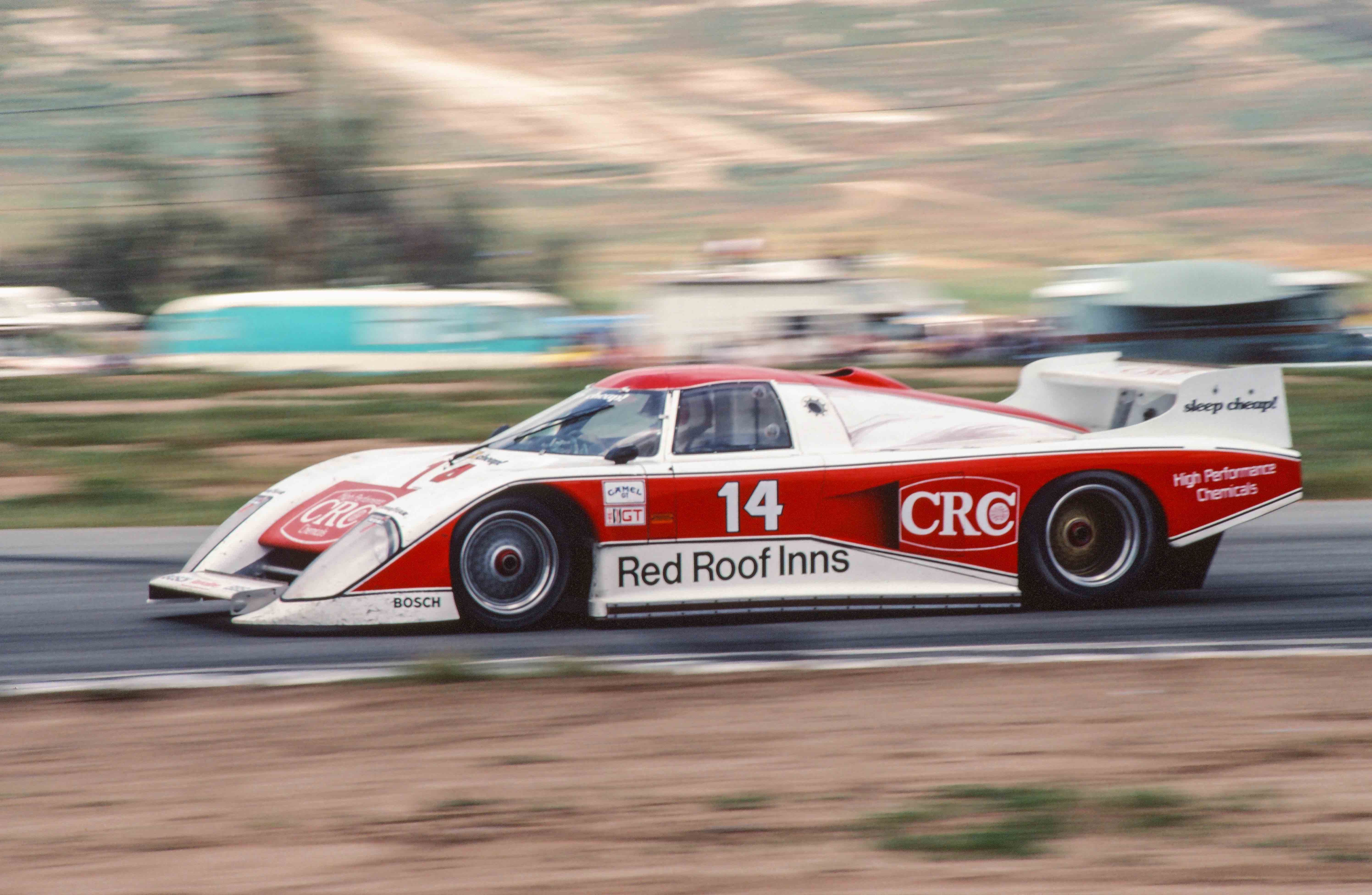

The biggest news of the 1983 season was the return of Al Holbert, who had been pursuing Indy Car and Can-Am glory. Holbert started the season by sharing Bruce Leven’s Bayside Disposal 935 with Hurley Haywood at Daytona and Sebring. But his main focus was on a CRC Chemicals–sponsored March 83G, initially fitted with a small-block Chevy V8. Holbert won with the car the first time it was entered, at the inaugural, but rain shortened, Grand Prix of Miami. After skipping the Road Atlanta round, Holbert finished second at Riverside and won Laguna Seca, after which he sold the car to Kenper Miller and Dave Cowart’s Red Lobster team.

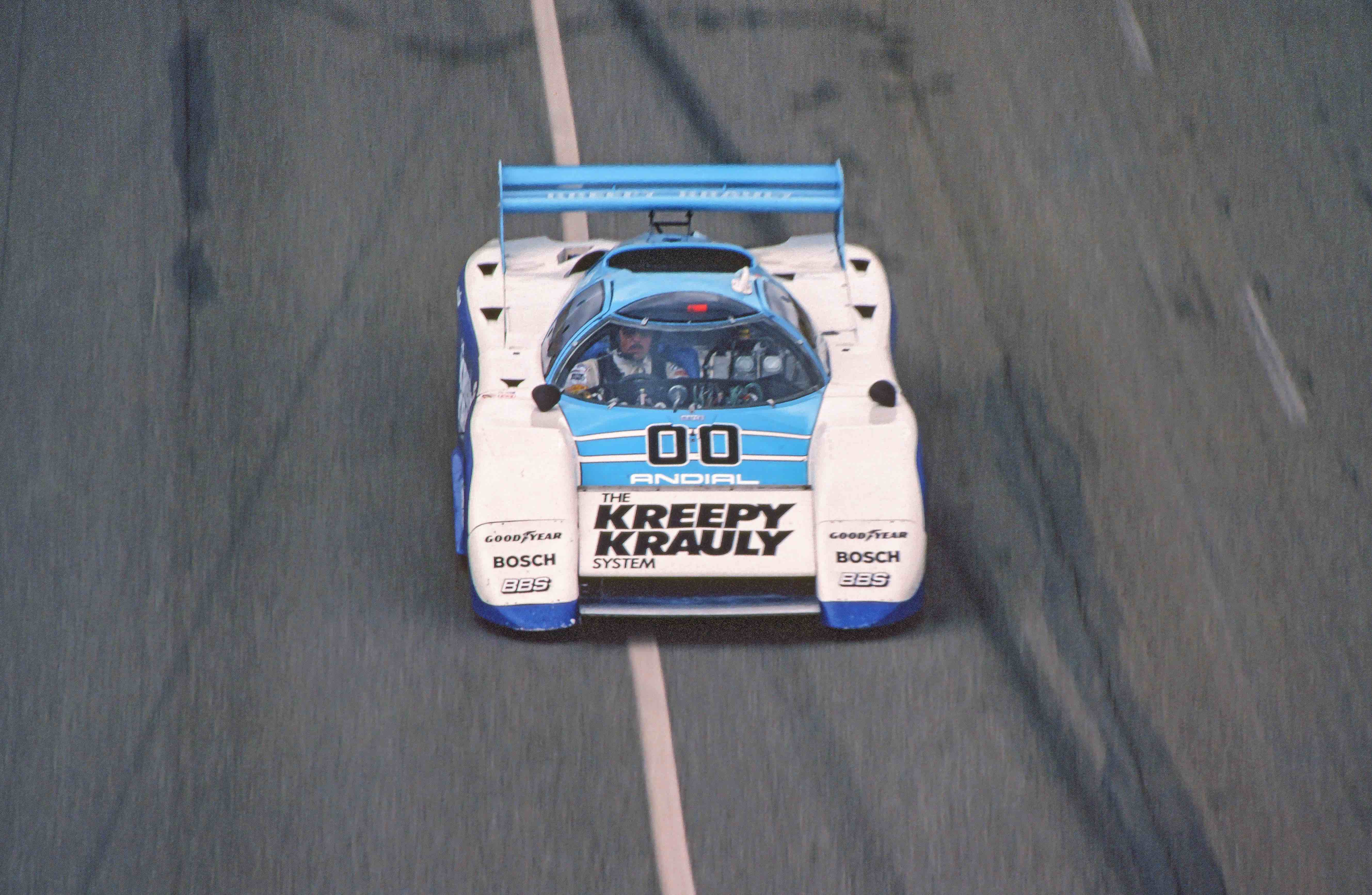

Holbert had another ace up his sleeve: a brand-new March 83G, this time fitted with an ANDIAL-prepared Porsche 934 single-turbo engine. Despite skipping the Mid-Ohio and mid-summer Daytona events, Holbert easily took the 1983 Camel GT title by winning with the new Porsche-powered car four times and scoring points in another seven races.

Al Holbert’s triumphant return to IMSA competition in 1983 came at the wheel of a March 83G fitted with small block Chevy V8, shown here at Riverside. He later switched to a new March 83G chassis fitted with a single turbo Porsche 934 motor and won the 1983 Camel GT championship. Photo: Kurt Oblinger

One of the prettiest GTP cars of the era, the ex-Holbert Racing Porsche-powered Kreepy Krauly March 83G of Sarel Van der Merwe, Tony Martin, and Graham Duxbury, won the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1984, pictured here at Riverside in the 1984 season. Photo: Kurt Oblinger

The Blue Thunder Marches of Bill Whittington and Randy Lanier, sponsored by Apache Powerboats, dominated the 1984 Camel GT season with six wins, including one here at Watkins Glen, giving the title to Lanier. Photo: Whit Bazemore

With the introduction of the Porsche 962 into the Camel GT Series in 1984, it wouldn’t take long for Porsche to once again dominate U.S. sports car racing. The 1984 championship in the hands of Randy Lanier driving a Chevy-March would turn out to be the last for a March-based car in the series. But not without a fight.

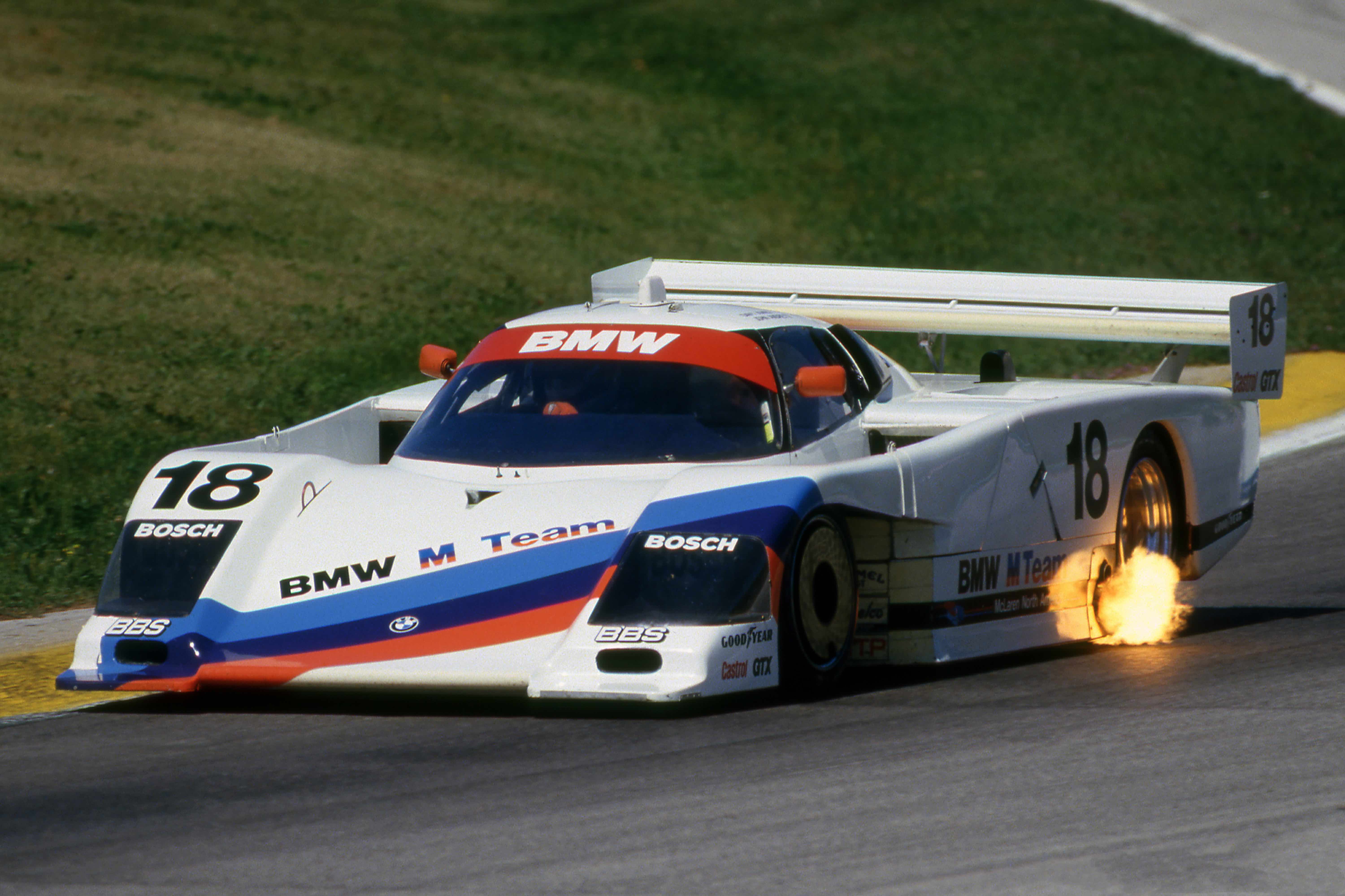

BMW decided to renew its Camel GT program by entering a March 86G chassis for David Hobbs and John Watson in the 1985 season-ending race at Daytona. As before with the 320i program, McLaren North America prepared the cars and ran the team. By this time, BMW’s 1.5-liter turbocharged Formula One engine was well developed and reliable. It was the same engine used by Nelson Piquet to secure the 1983 Formula One World Championship. It was adapted in a 2.0-liter form for the March 86G, the first prototype designed entirely using computer-aided design equipment. Power output was a reputed 1,100bhp with the boost turned up.

A second car for John Andretti and Davy Jones was built early in 1986, but during testing at Road Atlanta, it was destroyed in a fire caused by a fuel line that had been loosened by an engine vibration. The same vibration caused a serious, end-over-end crash in practice at Sebring when the rear cowling flew off, destroying a second tub, and forcing the team to withdraw.

Given the teething issues and destroyed cars, Bob Riley and a host of all-stars were brought in to help sort things out. After working flat out, the team turned the BMW-March into a very fast but still inconsistent car. The team skipped a few races during the 1986 season, but the car’s outright speed was evident whenever it showed up. After winning the pole at Road America, Jones survived a horrific high-speed crash in the race just after the kink in the backstretch when he put two wheels off in the grass on driver’s left. Bad luck and mistakes seemed to dog the team.

The BMW March 86G was a generation ahead of the rest in terms of aerodynamic grip and raw speed in 1986. Reliability issues kept it from doing well much of the season. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

However, the team’s triumphant moment arrived in one spectacular win at Watkins Glen with Andretti and Jones at the wheel. The two BMWs started on the front row and the winning car lapped almost everyone else in the field. In spite of the promising result and the car getting faster without direct factory support from Germany, BMW once again withdrew from IMSA after the Daytona finale at the end of 1986. David Hobbs lamented the decision, saying, “We could have cleaned the table with that car in 1987, it was probably the fastest prototype I ever drove.” Two of the March 86G chassis were sold to Gianpiero Moretti, who installed Buick V6s (one was a turbocharged 3.0-liter and another was a 4.5-liter normally aspirated motor) and raced them the following year.

The BMW March team scored its most impressive weekend at Watkins Glen, with both cars on the front row and John Andretti/Davy Jones taking the overall win in convincing fashion. Photo: Tony Mezzacca

When BMW canceled its IMSA GTP program at the end of 1986, Gianpiero Moretti purchased the March 86G chassis and installed turbo-powered Buicks for the 1987 season. He co-drove here at Sears Point with Whitney Ganz. Photo: Richard Bryant