“At Mosport, we had a little rev problem, and were over-winged, but we hung in there for seventh. Here we’ve learned a little more. We were getting it all to work for us until that pump died on the start, and we got disqualified. But that’s racing, you know… Hopefully, we can make it a better car yet, and really, it’s so good to be here again in Formula 1, it really is. It’s the thoroughbred of racing, you know it’s the top…” Mario Andretti, Watkins Glen, October 1974.

Mario Andretti wheels the Vel’s Parnelli Jones Formula One car at Watkins Glen in 1974. Photo: International Motor Racing Research Center.

Back in 1974 at Watkins Glen for the United States Grand Prix, I got the chance to sit down with Mario Andretti – in the Vel’s Parnelli Jones team’s section of the Glen circuit’s Technical Centre – and hear from him about his life and career that far. Mario came across as a hyper-competitive sportsman of great – and continuing – achievement and experience and, as a man, he was friendly and engaging and one who conducted himself in a gently distinguished (and highly impressive) manner.

To me, as a hopeless race reporter – by temperament far too shy and reserved ever to ask questions of anyone to whom I had not yet been introduced – the time Mario gave me that day seemed incredible. How had I got to him? Well, both Vel’s Parnelli designer Maurice Phillippe and team manager Andrew Ferguson were fellow Brits, ex-Team Lotus in England.

I knew both well from Lotus days, and it was Andrew who overcame my natural reticence – called me over and said “Hey Mario – here’s someone you ought to meet – he’s OK”. So, there at the Glen that day, I taped a long conversation with America’s finest Italian-born racing driver. And here’s the feature story based upon it that I put together over the next few days. – Doug Nye

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

It took just under four minutes for Mario Andretti to make himself an ace. To be precise he took 3 minutes 46.63 seconds, pelting his Dean Van Lines Special round Indianapolis to steal pole position and set new four-lap and one-lap qualifying speed records, first time out on the Speedway.

Mario Andretti poses in his Dean Van Lines Brawner-Hawk after qualifying fourth for his first Indianapolis 500 in 1965. He would finish in third and win rookie of the year honors.

That was nine years ago, in 1965, and until then Mario had been just another successful young kid from the dirt tracks, full of apparent potential in his first few USAC Championship races, but yet to deliver the goods. As he pulled his bulbous white Ford-powered car into the Indy pit lane the crowd roared themselves hoarse at his performance. But the wiry 25-year-old Italian immigrant was already looking over his shoulder. Jimmy Clark followed him out onto the Speedway, and he turned in four consecutive laps over 160 mph to steal Andretti’s pole position and his records. At the end of the day, A. J. Foyt had taken top qualifying honours, and Mario was fourth quickest, bumped back to the inside of the second row by Dan Gurney. In the race, his first Indy 500, the tough little man from Nazareth, Pa, then drove like a veteran, despite an intermittent fuel system fault afflicting his car. He lay with the leaders from the start, hounding Rufus Parnelli Jones all the way until the race drew towards its dramatic finish.

Clark rushed home to win for Lotus and Ford, nearly two minutes ahead of Jones’ year-old Lotus which was in deep trouble. It was running low on fuel, and with Andretti just 20-seconds astern, Parnell dared not stop to top-up. On the last lap, Jones zig-zagged his faltering car across the line, just managing to wash the last remaining dregs of fuel into the pick-up pipes, to hold off Andretti by just six seconds.

So the mercurial Rookie was third in his Indianapolis debut, winning a well-deserved Stark & Wetzel Rookie of the Year award, and also being voted Driver of the Year by the Hoosier Auto Racing Fans. They knew what they were talking about. He ended the season by winning the USAC National Championship, and he repeated this feat the following year.

Since then Mario Andretti has become Internationally-acknowledged as one of the most versatile and capable race drivers of all time. He has won on dirt and paved ovals; he has won stock car races on the high-banked super-speedways of the American deep south; he has won on road circuits in USAC Championship cars, long-distance sports car classics, in Formula 5000 and in Formula 1.

In 1969, he won the prestigious Indy 500, and in 1971 he won the South African Grand Prix. He is back in Formula 1, driving for the prime target in that now far-off Indianapolis 500 —for Parnelli Jones. His brand-new Maurice Phillippe-designed Vel’s Parnelli VPJ4 made its debut in ‘Super-Wop’s’ hands in the Canadian GP, and he perched it briefly on pole position for the United States GP at the Glen. Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones now have their team poised to tackle a full World Championship season next year, and after their spoiled Watkins Glen performance, they obviously mean business.

I found Andretti in the Kendall Tech Centre at the Glen after the Grand Prix’s first practice sessions had ended. He had set fastest time. The car was on pole overnight, and there was no mistaking the heart-warming rosy glow around the Vel’s Parnelli work bay.

The Tech Centre at the Glen is a great gloomy barn of a place, fenced off into a series of bays with a spectator-packed aisle down the centre. They pay a dollar a time to pack into the place for a close-up look at the great cars and great names of the day. The place is reminiscent of any English country-town’s covered cattle market, but here the all-pervasive pong is one of synthetic rubber, oil and cleaning fluid, instead of you know what.

Mario is a deceptive character, small in stature, broad-shouldered and powerfully built. He’s a big man in attainment, and he wears competitive nature like a badge. It’s as unmistakable as the Ferrari escutcheon which he still wears proudly on his Firestone jacket.

Motor racing was just starting its final pre-war season, confined to Italian territory, when Mario and Aldo Andretti were born as twins on February 28, 1940. Father was a farmer, and the family had seven farms in lstria, around Trieste where the Adriatic bites the division between Italy and Yugoslavia. At the end of the war, the Andrettis’ land was swallowed by a political settlement with Yugoslavia. The family wanted to stay Italian as the border was adjusted, so they abandoned their heritage to the new communist state and joined thousands of refugees moving westward.

Andretti is matter-of-fact about what must have been at first a confusing and later a bitter experience for a young kid. “We left in 1948, and lived in a refugee camp at Lucca—it’s near Pisa—for the next seven years. Yeah, it was tough. There were twen’y-seven families all living in one big room, about the size of this…”, he said, waving his hand at the Tech Centre’s walls.

“It was in Lucca that Aldo and I started around the local garage. The guy who ran it had ambitions for his son in racing, bought a Stanguellini and kind of pushed him into it. We were only around t’irteen or fifteen, and we used to help around and just soaked up the racing atmosphere. I remember there was one really great day, we went to Modena to pick up a ’53 Ferrari for the Mille Miglia, that was a great thing… “.

“We had an uncle, he was a priest, called Ghersa Quirino, and I guess he sympathised with our ent’usiasm. He bought us a 175cc MV motorcycle, without our parents knowing, and we raised hell with that around Lucca— all these little tight streets and alleys you know, it was the ideal training ground. We really loved motorcycle road racing…” (expansive gesture with the hands) “…any kind of road racing, and then we had great aspirations to get properly involved sometime.”

The family had relatives already living in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, and they acted as sponsors to help Mario’s folks emigrate there in the late ’fifties. By that time Mario and Aldo had driven their first motor races in an 85-horsepower Stanguellini-Fiat Formula Junior car, and they came to America hoping that at least one thing would not have changed much in their new life.

They were in luck. Three days after arriving in Nazareth they heard the rumble of modified stock cars racing on a nearby track: “We got over there quick as we could. We looked at the people driving and at the cars they drove and thought ‘hey, this looks easy’, and that was that….”.

The twins had another uncle, Louis Messenlehner (“…he was German, you know, on my mother’s side…”) who helped them to learn the language and, clandestinely so their parents would not suspect, to put together a modified stock car of their own.

“It was an old ’48 Hudson. Marshall Teague had been king in those cars until he was killed the year before we got started, but his folks and mechanics gave us all their know-how on spring-rates and shockers; it was pretty much unknown sophisticated stuff at that time.

“You had to be 21 before you could race in America, and we were only 17, but Les Young who was a newspaper editor on the ‘Nazareth Key’ helped camouflage our date of birth and we got in there. Aldo won the first race from starting at the back. We won our first three events, you know, we were quite successful all through our stock car days…”.

They had some low notes, as when in their first season (1958) Aldo got the Hudson out of shape and crashed heavily during a race at Hatfield, Pa. He suffered a concussion, and Mario had a hard time convincing Papa that Aldo had accidentally fallen off the top of a truck while watching the racing.

Unfortunately, Aldo was never again to be quite such an accomplished natural driver as his brother, and after trying hard in midget and sprint cars, he sustained severe head injuries through crashing a sprinter in 1969 and hasn’t raced since. Today he lives in Indianapolis, runs a couple of Andretti Firestone tyres stores, and accompanies his brother to most of his races.

In 1958, ’59 and ’60 Mario won over 20 modified stock car events, and in 1961 moved into the single-seater scene on the URC Sprint Car circuit. He was old enough to race legally but had some problems making the transition. “I just didn’t know which way that car was goin’ to go”. He ran with URC until the middle of 1962, when he began driving midgets in ARDC.

It was a rough and tumble schoolroom, of a type simply non-existent in Europe, which provided a staggering amount of experience: “I did 107 races in 1963, you know…

“In Midgets, you can regularly do 80 races on up each year. Sometimes we’d do t’ree races a week, and on Labour Day ’63 I won three races in two meetin’s ! Today just physically you can’t do that, but those Midgets really were the most constructive racing I’ve ever done. I tell you, you never run closer than in Midgets. You’d have 45-50 cars to qualify for only 18 places in the Final, and winning in Midgets can give tremendous satisfaction. I really felt I was accomplishin’ somethin’.”

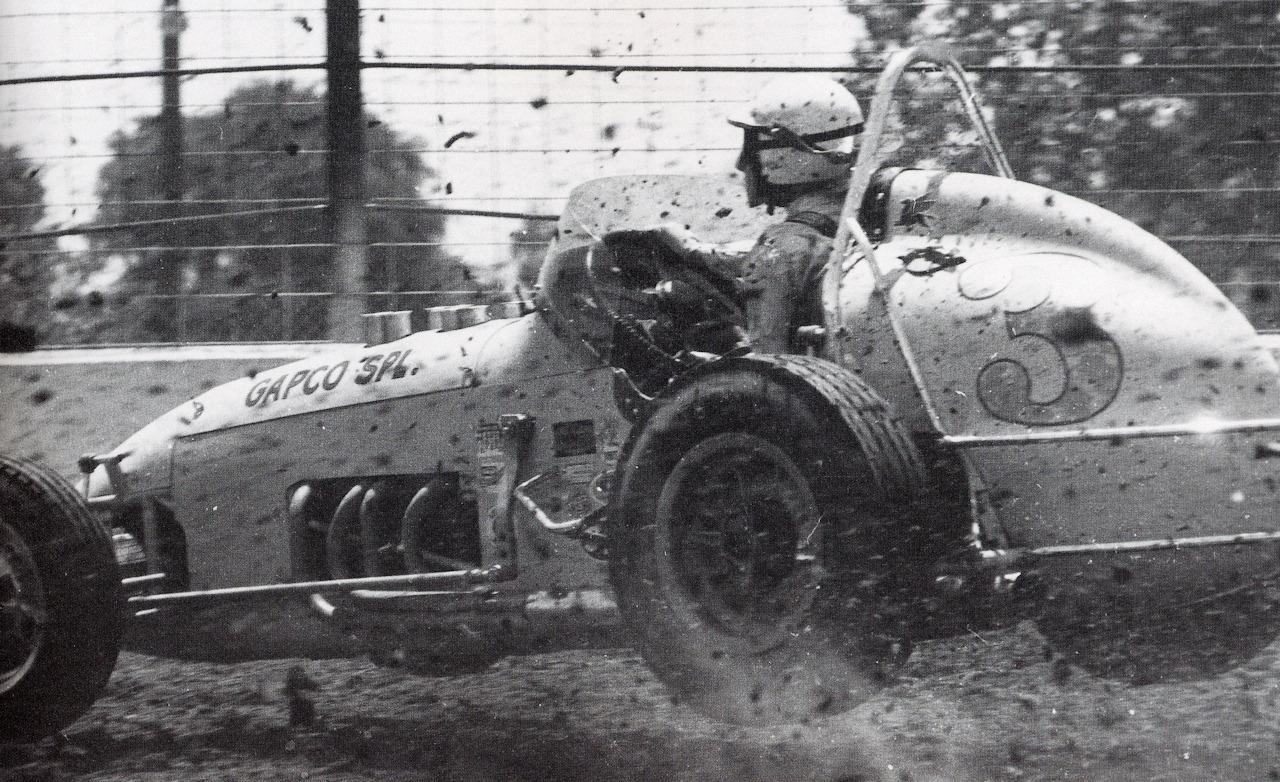

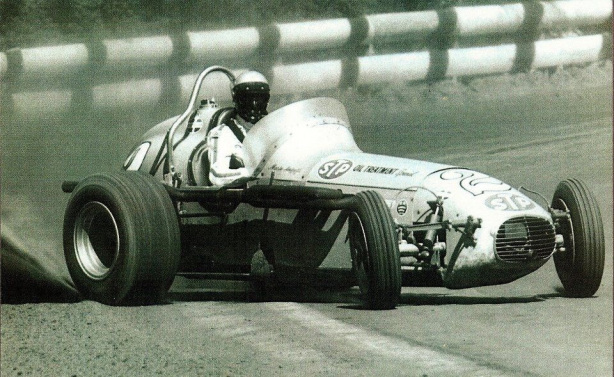

Andretti continued to race Sprint cars on dirt even as his international racing career took off, as pictured here at Terre Haute in 1965.

He drove an Offy-powered Midget for Bill and Ed Mataka that season, and early in 1964, he joined the United States Auto Club to get into Championship racing, to tackle the big-time. “That had been my goal since I started in sprints, you know. When you’re just starting you gotta set your aims high; unreasonably high at the time, and you just gotta get out and get after them. You tell yourself to do it…”, a shake of the head, “Shit, you just tell yourself these things, you know….”

Mario hangs in out in the dirt at Sacramento in 1966.

Mario’s first Championship race was at Trenton, NJ, in March ’64, and it wasn’t too happy a debut. “I was like a fish out of water. I mean I spun three times. I tell you, I just felt incapable! Those paved tracks were hard to drive at first. I was used to hanging my Sprint car out and tossing it around. In comparison those roadsters were a son of a bitch, you had to drive ’em like t’readin’ a needle…”

The story goes that Mario visited Indy that year; just a 24-year-old dirt track driver soaking up the Speedway’s carefully manufactured mystique for the first time. But he wasn’t overawed by the place. He was wandering around Gasoline Alley looking for a drive. He looked up Al Dean’s veteran crew chief Clint Brawner, who had just lost his driver when Chuck Hulse was seriously injured in a sprint crash earlier that month. Rufus Grey, who owned the sprint car Andretti was driving at the time, introduced his young protégé and tried to talk him into Brawner’s Dean Van Lines roadster. When he mentioned that Mario raced sprint cars, Brawner’s sun-sensitive neck apparently reddened, he bawled “Goddammit, sprint’s a dirty word in this garage”, and tossed the hopeful applicants out of the door!

But Brawner had heard of Andretti’s prowess from other sources, and a month later he watched Mario drive at Terre Haute and offered him the Dean drive, mere or less as a trial until Hulse recovered. The compact little Italian jumped at the chance; “In major league racing, I figured there were only a few outfits worth driving for, that were going to produce a winner. I considered Dean one of these, so I t’ought maybe I’m gettin’ into somethin’ good.”

He drove the Dean Van Lines Special in the last eight Championship races of the ’64 season, was third in the Milwaukee ‘200’ and notched sufficient points for 11th in the Championship standings. He drove in 20 sprint races, was third in the standings and highlighted with victory in the Joe James-Pat O’Connor Memorial 100-lapper at Salem.

— Continued in Part Two

Born in Milan in 1905, Luigi Chinetti is best known for being the exclusive distributor of Ferraris in the U.S from the beginning of Ferrari’s firm immediately after World War II. Long before that happened, he began to build a resume when he secured a minor’s work permit from the Italian government as a lathe operator when he was twelve and another as a machinist when he was fourteen. He met Enzo Ferrari when they both worked for Alfa Romeo in the 1920s.

With the rise of Fascism under Mussolini, Chinetti became uncomfortable in Italy and moved to Paris the mid-1920s. He began to race, winning Le Mans in 1932 and 1934. Before the war, he was associated as both a driver and team manager with private and factory entrants that ran Alfa Romeos, Talbot-Lagos, Delahayes, Delages, and Maseratis, bringing a pair of the latter to the 1940 Indianapolis 500 in 1940. His Indianapolis adventures before the war led to his becoming the most important bridge between the European and American road racing worlds after the war, at a time when much more than an ocean separated them. He secured an entry for many Americans at Le Mans and other European events as well as promoting Americans through his North American Racing Team and by placing some with the Ferrari works team. The latter included Phil Hill, the only American-born World Grand Prix Champion, who drove a Ferrari to the title.

While Chinetti was at the 500 in 1940, the Germans were completing their invasion of France and would take Paris on June 10, 1940, just ten days after the Indianapolis race. Chinetti remained in the U.S., during the war. Afterward, he spent long periods in Milan, Modena, and Paris and was the sole French importer for Ferrari for a while. He also added to his racing reputation, winning Ferrari’s first big international victory in a 12 Hour race in 1948 at Montlhéry, France, where he drove the entire race by himself. He also won his third Le Mans the following year in another Ferrari. These early victories led to Ferrari putting some orders on the books at a time he desperately needed them. Despite his European connections in France and Italy, Chinetti’s primary home remained in New York, and he became a U.S. citizen in 1950.

The Montlhéry car was a 166 Spyder Corsa, and after some successful record runs late in 1948, the car was sold to the leading entrant in the post-war revival of U. S. road racing, Briggs Cunningham, a wealthy sportsman. When he bought the 166 in the fall of 1949 to take part in a race at Bridgehampton, it had not been freshened since the record runs. This did not sit well with either Cunningham or Alfred Momo, an Italian immigrant who prepared Cunningham’s cars. Nonetheless, the Ferrari led easily until an oil line behind the exhaust header broke and could not be repaired in time, so the car was retired, becoming the first Ferrari to race in America. Once Momo got the parts he needed, the 166 also became the first Ferrari to win a race in America (Suffolk County Airport 1950).

There was some friction between Cunningham and Chinetti because of the condition of the car when delivered, but Cunningham’s later success with it softened Cunningham’s view and he was soon ordering another Ferrari from Chinetti. This was a 195 S, featuring bodywork by Touring of Milan, a beautiful Le Mans coupe.

American sports car racing was run at the time by the Sports Car Club of America, which had a strictly amateur policy. This was to discourage professional oval drivers from taking part in SCCA events. There was no prize money and anyone who raced for money anywhere would lose their SCCA license. The SCCA people did not want the professionals beating them. Another consideration was a class one. Many SCCA participants were preppies from St. Mark’s, St. Paul’s, Andover and the like and had matriculated to Harvard and Yale. The leaders of the club definitely believed in “the right crowd and no crowding.” The Indianapolis drivers were working class and were looked down upon socially, if not in talent. This type of attitude also led to discrimination against Jewish membership applicants, let alone blacks and Latinos. More enlightened leadership was soon elected.

Alec Ulmann was a Russian émigré who had an aviation business at a largely unused airport in Sebring, Florida. He had been involved in the organization of the earlier Watkins Glen and Palm Beach Shores races and was a proponent of professional racing in America. He organized a six-hour event at a leftover B-17 bomber training base in Sebring, Florida, to be run on New Year’s Eve 1950, hoping to create a race as prestigious as Le Mans and other classic European endurance races.

Photo credit: Jack Cansler

The image here of Cunningham’s coupe at Sebring that day brings to mind a number of historic events. One is that when the car arrived at Momo’s, it smoked badly when it was started. Cunningham was outraged, as he planned to drive the car in the race. Chinetti simply told him that the rings had not yet seated and everything would be fine. Cunningham switched his ride to an Aston Martin DB2 and suggested that Chinetti and Momo drive the Ferrari.

As was so often when cars and their engines were concerned, Chinetti was proven to be correct. Once again driving alone, he brought the little Ferrari coupe home in 7th on handicap and fifth on distance. Cunningham’s Aston was 17th and 8th.

Another dust bunny of history is that despite the notoriety of Luigi Chinetti’s North American Racing team from the mid-1950s, this was the only time Chinetti himself raced in America. He came from the European tradition of prize, accessory and starting money and had little interest in entering one of his $12,000 Ferraris in a race where the winner would receive a silver cup or engraved tray.

Cunningham and Chinetti would share one more dispute about a Ferrari, four years later. But that’s another story.

-Michael Lynch, Member of the IMRRC Historians Council

Here is many Americans’ favorite Grand Prix driver Dan Gurney taking the Nouveau Monde hairpin at the bottom of the Rouen-Les Essarts public road circuit during the French Grand Prix on July 8, 1962, in the Porsche 801 flat-8 Grand Prix car. The Porsche was a rather new car and had recently undergone substantial suspension and bodywork revisions based on extensive testing at the Nürburgring. Gurney was not forecast to be particularly competitive – in fact, he was back on the third row of the grid – but with some attrition, he surprised everyone by taking an unexpected victory.

The week before the French race all the British teams, Lotus, Cooper, Lola and BRM, had been at the super-fast Reims circuit for the non-Championship Reims Grand Prix, the new name for the prewar Grand Prix de la Marne, joined by two privately entered Porsche 718s. Ferrari, although entered, as here at Rouen, did not show up due to metalworkers strikes in Italy.

To whet the attention of the spectators, race day began with two Formula Junior heats and even a bicycle race. But soon things got down to some real F1 racing. At the start, seen here, Graham Hill in his BRM 57 leapt out to small lead ahead of Jim Clark’s Lotus 25, Bruce McLaren’s Cooper T60 and new F1 driver John Surtees with the Lola 4-Climax. Gurney was back in sixth place but stayed in touch with the leaders. His teammate Joakim Bonnier had the second Porsche 801, but was not at Gurney’s level, the American having received the majority of the Porsche mechanics’ attention during practice.

Before long McLaren stopped at the pits, but continued a couple of laps in arrears while Brabham brought his Lotus in to retire with broken suspension. At half distance it was Graham Hill still out in front with Clark’s Lotus in second and now Gurney up to third. Clark set a new lap record, but the decided all was not well with his car and came into the pits which left Hill in the lead by some 30 seconds over Gurney while Surtees’ Lola was third but a lap down. Then, with 12 laps to go, Hill pulled off at Nouveau Monde with injection troubles which gave Gurney the lead which he carefully held to the finish. The tail-enders also found that it pays to keep running as Tony Maggs with his Lotus was second one lap down and Richie Ginther in the second works BRM was third, two laps behind.

Because of Ferrari’s absence, their World Champion Phil Hill was but a spectator at Rouen, busy taking photographs with his Leica.

Photos by Louis Klemantaski ©The Klemantaski Collection – http://www.klemcoll.com

If the idea of a blog post is to pass along personal history having subject matter that might appeal to others, then here goes.

For me, autumn of 1948 was a pivotal time. I was fifteen and already riding an Ed Iskenderian-tuned 500cc Triumph Tiger, getting about on it, nicely enough, quickly enough, but my father decided I should step up and learn to handle a four-wheeler. The car of choice, his daily driver 1938 Type 57C Bugatti, offered me the first real steering wheel to grasp while comprehending the left-handed shift pattern of that straight-8 drophead French classic. Perceived as totally unearthly, the affair launched my sensibilities into what the outrageous world of cars truly was and, by the second day of October, I was all set to savor the outcome of America’s first post-WWII grand prix race run in anger over a 6.6-mile road course skirting, and slicing through, the hamlet of Watkins Glen, New York. The impression formed was permanent.

Invited 64 years later to speak on sports car racing in America at the Glen’s International Motor Racing Research Center, brought me to meet IMRRC’s president, J.C. Argetsinger, son of Cameron and Jean Argetsinger, founders of the first Watkins Glen Grand Prix and, later, the IMRRC facility. We talked about how it all began.

“Cameron Argetsinger,” J.C. said of his father, “was fascinated with the Roosevelt Speedway before the war when Mercedes and Auto Union came over, and after the war he bought an MG TC and joined the new Sports Car Club of America.” The story goes—during the SCCA members’ dinner at Indianapolis the night before the 1948 “500”, Cameron, a willing enthusiast from New York State, daringly announced he was “going to have a road race next fall” and invited everyone to join his entry list. The nerve of that young visionary! But they did join; not all, yet there were enough drivers and cars signed on to fill that historic grid for Watkins Glen’s inaugural Grand Prix on October 2, 1948.

“I sold programs that first year at age six,” Cameron’s son J.C., now 78, said. “There were ten or fifteen thousand spectators, and our city fathers liked the idea. Next year there were fifty thousand. By 1950 it was colossal.” Watkins Glen’s racing and the later research center grew hand in hand.

The IMRRC’s archives, after years of database streamlining and simplifying, is expediently searchable—punch in a name or date, place or car, it brings up anything out of a collection, and it’s right there. “We’re not a museum, per se,” informed an IMRRC archivist, even though renowned race cars are often displayed there, “and I think that’s important for people to know. It’s about the history of motor racing worldwide. It’s not just about Watkins Glen.”

Bygone beginnings are fascinating for anyone who fancies automotive history, as do I, especially American motor-racing’s golden era. Take, for example, the Italian gem bodied by Carrozzeria Touring that won that very first Watkins Glen race—an Alfa Romeo 8C2900B Berlinetta then owned and driven by Cameron Argetsinger’s colleague, Frank Griswold. Like my father’s Bugatti, Griswold’s Alfa was a straight-8, also built in 1938. Throughout high school, I penciled pictures of the swoopy 8C during study hall. I made it my dream car, even more so than the Bug. Sure, I could hop in and drive our Bugatti, but that Alfa—it was unobtainable! You might even say it only existed for me through shapes clouds made in the sky. And then.

Eleven years ago, on a chilly, damp November day while photographing and writing article notes about a Washington State vintage car shop called Dennison International, proprietor Butch Dennison led me to a bay where they were frame-up restoring a car to have ready for Pebble Beach’s Concours d’Elegance. And there it was!—the exact same Alfa Berlinetta that had won the Glen’s initial race and that had been stuck in my mind for all the decades since!

“Butch,” I gasped, “come August this car is going to win Best of Show!” He laughed, smiled, shaking his head in that fashion of possessing desire but not audacity to be certain. “You’ll see,” I said.

On August 17, 2008, the superbly restored Alfa Romeo 8C2900B was called forward to the Pebble Beach awards ramp where its owners, Jon and Mary Shirley, received the Concours d’Elegance’s Best of Show distinction—the Alfa’s second major historic win of its 70-year car life. I was there and was camera-ready. From a storm of swirling yellow and white confetti appeared the perfect story.

The conservancy of significant cars and keeping of their valued histories are both pursuits and obligations. But more than that, they are what we enjoy doing—and are the spirit of what I have seen grow from 1948 to today as the International Motor Racing Research Center at Watkins Glen, New York.

These narratives to be born from the IMRRC are for everyone caring about what we love.—William Edgar

Author: Martin Raffauf

All photos: Jerry Woods

Dick Barbour raced at the 24 Hours of Le Mans as an entrant for the first time in 1978, where he entered two Porsche 935’s in the special IMSA class at the classic French enduro. Barbour had started racing in IMSA in 1977 after having bought one of the original ten Porsche 934/5 models offered by the factory for IMSA racing that year. He ran some of the IMSA races with mixed success, but towards the end of the season, he and Bob Garretson signed an agreement that committed Garretson Enterprises to prepare Dick’s car(s) for the 1978 season.

Garretson Enterprises was an independent Porsche repair shop in Mountain View, California that had made a name for themselves in 1977 by preparing Walt Maas’ IMSA GTU championship-winning Porsche 914-6. The team entered eleven races that year and won eight of them, and finished second, third and fourth in the others, winning the championship over the factory Datsun 240Z of Sam Posey run by Bob Sharp. They had also prepared the winning car at the 1976 Pikes Peak hill-climb, a Porsche-powered buggy for Rick Mears.

Dick was looking to expand in 1978, so he ordered a new 935-78 (77A) for Daytona. His old 934/5 from 1977 would need some work and investment to update it to full 935 specifications. With Johnnie Rutherford and Manfred Schurti as co-drivers, he finished second overall at Daytona with the new car, after being delayed by a blown tire in the banking which lost a lot of time for repairs. For Sebring, two cars were entered, and although Dick’s main car faltered when a shock broke and punctured an oil line, the second car driven by Bob Garretson, Brian Redman and Charles Mendez (the race promoter), won the race. That car was immediately sold to John Paul Sr. after Sebring.

After Sebring, where I started with the team, we started preparing for two more US races, Talladega and Laguna Seca, then Le Mans. The second-place Daytona car (serial number 930 890 0033) ran at Talladega and finished third with Dick and Johnnie Rutherford driving. For Laguna Seca, we entered two cars, one for Dick, who finished sixth and one for Bob Bondurant (which was the updated 934/5) who ended up seventeenth. Then came the big push to get everything ready for Le Mans. In those days transportation for the car was usually done by boat, so a long lead time was required.

Although I was working with the team quite a bit by then, I was not going to the races (except for Laguna and Sears Point), as the traveling schedule had already been determined. I helped get everything prepared and loaded and then wished the team well. Steve “Yogi” Behr from New York (an IMSA racer from time to time) came and drove one of the trucks back to New York for us to get it to the ship, as there were no other people available to make the drive.

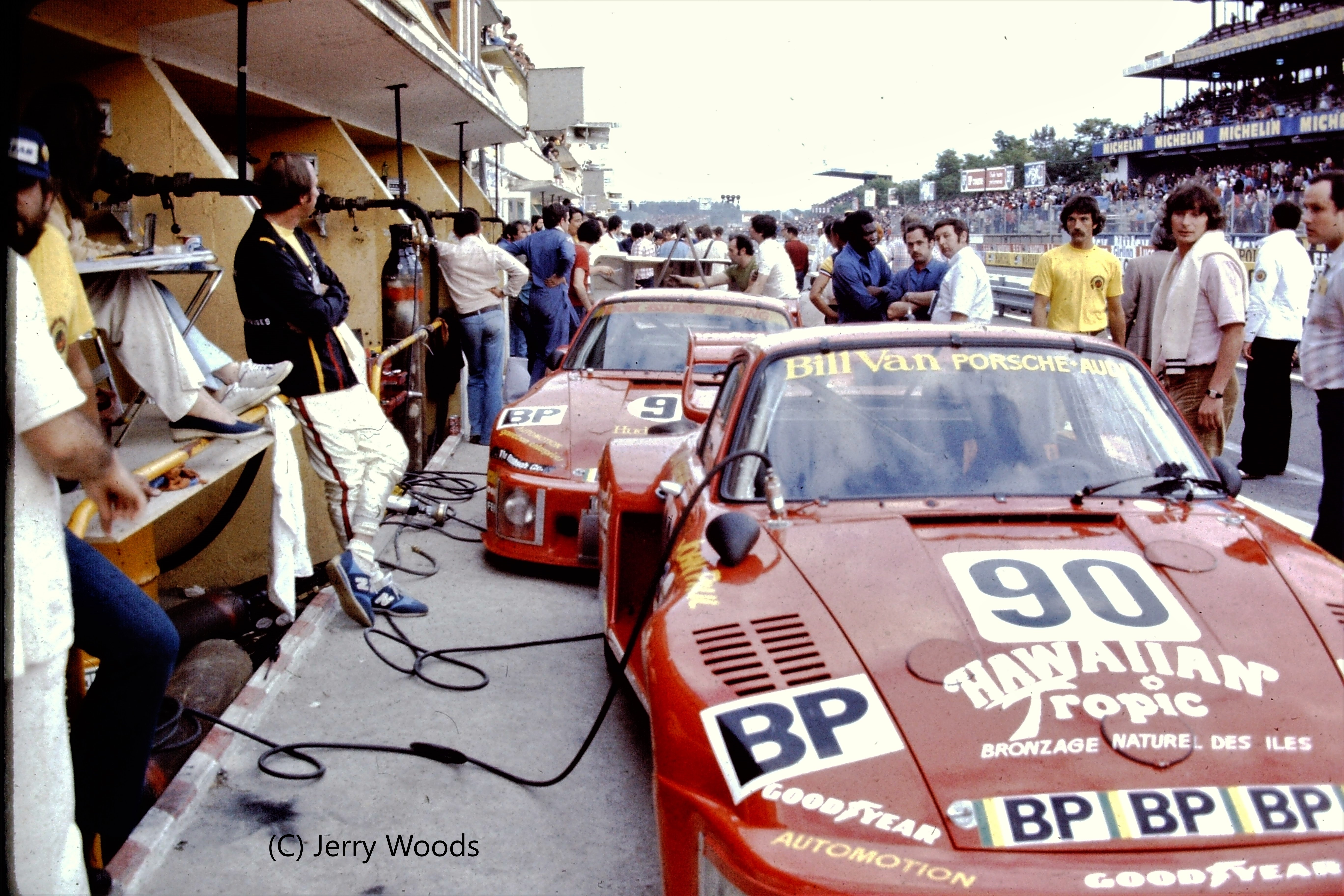

Dick had ordered a brand- new twin turbo 935 from the Porsche factory for the race. Gary Evans, the team manager, had gone over to Germany to order it earlier in the year (serial number 930 890 0024). Gary and Jerry Woods went to the factory to take delivery before the Le Mans race. It was then delivered to the track by Porsche with the rest of their cars. It would run as #90, and be driven by Dick, Brian Redman, and John Paul Sr. The second car, which we had prepared in California, was a Porsche 935 (serial number 930 890 0033). This 935 was a single turbo model and would be driven by Bob Garretson, Bob Akin, and Steve Earle.

Dick Barbour Racing picks up a brand-new Porsche 935 from the factory just prior to the 1978 24 Hours of Le Mans. Gary Evans at Left, Bob Garretson and Sharon Evans at right.

The majority of the team had arrived the weekend before and set up in the Le Mans paddock. Several of the team stopped on the way and watched the Spanish Grand Prix at Jarama. At the Madrid airport, they ran into none other than Bill France Sr. of NASCAR, who gave them directions to the circuit. Ron Trethan, Greg Elliff, Brian Carleton, and Alan Brooking watched Mario Andretti win the Spanish Grand Prix in a Lotus 79. Many years later, Greg Elliff would restore the very same Lotus 79 for Duncan Dayton. At the race, they ran into Bill Broderick (the hat swap guy in victory lane!) from Union Oil (NASCAR). After the race, at the airport, all the drivers had already arrived from the track via helicopter. They had a beer with Jody Scheckter while waiting for the plane to France. By the time they got to the team hotel in Pontvallain France, it was very late and the place was already shut down as everyone had gone to bed. They slept on the sidewalk in front of the hotel and were woken early by the street sweepers. I guess that’s what happens when you travel from Mountain View, California to Pontvallain France for the first time! Pontvallain was just not set up for “late arrivals.”

Dick Barbour Racing crew gets set up in the grass paddock at Le Mans in 1978. As newcomers, we did not get prime paddock space in 1978.

The Le Mans circuit back then was very different from today. The Mulsanne had no chicanes, and the pits were old, and quite decrepit. The signal pits were at the far end of the circuit, many miles away at the Mulsanne corner. Radios back then were problematic, and in any case, the American radios did not work too well in France and were technically illegal to use, as you were supposed to have a French license to use any radios. Communications to the signal pits were via old crank up phones on the wall in the pit boxes. Paddock and team working conditions, were basic at best. Much of the paddock was not even paved, and as “newcomers”, the team got a prime grass corner in the back. The hotel was a small one in the town of Pontvallain which was well to the south of Le Mans, about a one hour drive.

The car as delivered by Porsche, needed some work to become IMSA legal as the rules for FIA Group 5 and IMSA were slightly different. IMSA rules required windshield retaining tabs, rear window straps, and a driver’s window net. New front air dams that had been built in California were fitted. These had been built by Jeff Lateer, and contained two headlights per side, thereby alleviating the need for the night hood mounted extra lights (lessening drag on the Mulsanne). The delivered drilled brake rotors were removed and replaced with longer lasting solid rotors.

Both Dick Barbour cars sit in the pits at Le Mans prior to the start of the 24-Hour classic.

Both cars were entered in the IMSA class, along with a bunch of Ferrari 512BBs, a few RSRs, one BMW CSL, and Brad Frisselle’s Monza. There were Group 6 prototypes from Both Porsche (936) and from Renault, as well as Mirage. These would be the cars to beat for overall victory. There were also quite a few Group 5 Porsche 935s and Group 4 Porsche 934s as well as 2.0-liter sports cars. All the 935s ran the 3.0- liter engine, some twin turbo, some single, except for the 935-78 from the factory which ran a 3.2 engine with water cooled heads. All the Group 5 935s weighed less than the IMSA version, as we had to run at the IMSA minimum weights to run in the class.

Both our cars qualified without difficulty. Redman got the pole in the IMSA class with a 3:52.6, Dick did a 3:56.6, and John Paul Sr. a 4:02. Bob Garretson qualified the #91 at 4:05, Bob Akin at 4:09 and Steve Earle at 4:13. Rolf Stommelen set a blistering time in the 935-78 of 3:30.9 to start third overall behind Ickx in the 936-78 at 3:27.6, and Depallier in the Renault at 3:28.4. The battle for the IMSA class would come down to our two cars, and most likely the Ferraris of Charles Pozzi and NART. Dick, having finished second at Daytona, was in an advantageous position to win the Daytona-Le Mans trophy for 1978. This trophy was awarded to the driver/team who did the best in the two races combined. Since the Brumos (Peter Gregg) team, which won Daytona, was not running at Le Mans, Dick just had to finish well up and he would get that trophy. That was a secondary goal of winning the IMSA class.

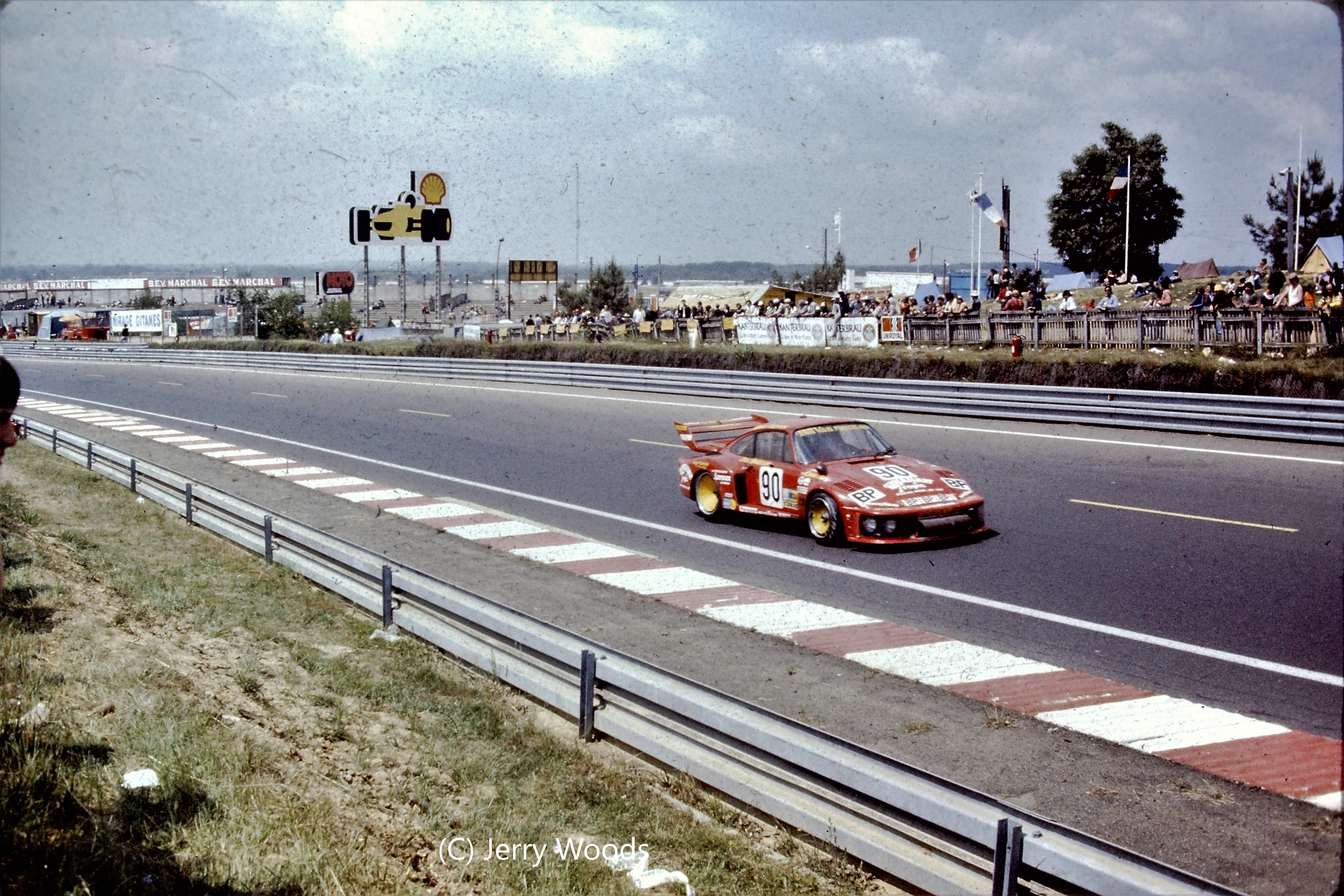

The number 90 Porsche 935 at speed at Le Mans in 1978. The car was shared by Dick Barbour, Brian Redman, and John Paul, Sr. and would win the special IMSA class that year.

The race started well enough. The strategy was to drive conservatively, finish, and win the class. Starting in the early stages, the #90 led the class and ran like clockwork. The #91 had a few issues, including troubles changing brake pads and a crash by Steve Earle, which required new front fenders and air dam. Around 3:50 am Sunday, #91 had an issue with the exhaust system, and 14 minutes were lost, but the car was still running. At 4:55 am Sunday, Bob Garretson went off the road at the Mulsanne kink, vaulted end over end on the side of the track on driver’s left. He doesn’t really remember what happened, and although he was dazed, he walked away from the crash. About the only thing he recalled was that the door was so smashed he had to crawl out thru the windscreen area. The windshield was gone completely. The car was pretty much destroyed. Brian Redman stopped at the site in the #90 car, checked to see if Bob was ok, then pitted to give a report to the rest of the team. Several of the crew went out to the crash site once it became daylight, and found Bob’s glasses in the dirt by the car.

The number 91 Porsche 935 wasn’t so fortunate, having crashed at high speed on the Mulsanne straight in the middle of the night. Driver Bob Garretson escaped unhurt, although he had to crawl out the hole the windshield used to occupy. The car was almost completely a write-off.

By the time we got it back to the shop in California, about all that was salvageable were a few gauges from the dashboard, some of the engine parts, and some of the gearbox parts. Most of the suspension, bodywork, chassis, roll cage etc. was all trash.

The #90 car ran trouble-free, just making normal pit stops for fuel, tires and changing of brake pads. The only real issue occurred at one point when team manager Gary Evans went looking for Brian Redman to get him ready for the next pit stop. He was getting worried when he didn’t find him in any of the driver caravans, which were all full of sponsors and others who weren’t supposed to be in there. Eventually, he was found sleeping in the canvas tire slings in the truck – disaster averted.

Brian Redman catches a nap between stints. Everyone, even the drivers, had to grab sleep when and where you could find it.

Since John Paul Sr. was driving with us, he brought his main mechanic, Graham Everett along. He and Greg Elliff changed the brake pads and did it well. According to Le Mans records, not one stop for this car was longer than two minutes. Even the Porsche factory guys on the 936 next door to us were impressed, as the #90 car was changing brake pads quicker than they were. Most of the race we were in a battle with the Group 5 leader, which was the Kremer car of our IMSA buddies Jim Busby, Rick Knoop, and Chris Cord. In the end, we finished fifth overall and won the IMSA class, and they finished sixth overall and won the Group 5 class. The Porsche factory at Werks 1 – Zuffenhausen had certainly done an outstanding job building 930 890 0024. Not one issue, and a class winner, first time out. The drivers did an excellent job and avoided any on-track issues, and the pit work was exemplary.

Dick Barbour had accomplished both goals – winning the IMSA class and winning the Daytona-Le Mans trophy for 1978. After that experience, he was hooked and would return to Le Mans again in 1979. But that’s another story.

Reprinted with Permission from PorscheRoadandRace (www.PorscheRoadandRace.com)

This is Part TWO of the behind-the-scenes story of how sports car racing emerged in America during the post-war era, who organized the races and the all-out war that erupted for control. This post is excerpted from the book: “IMSA 1969-1989: The Inside Story of How John Bishop Built the World’s Greatest Sports Car Racing Series”, authored by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, scheduled for publication in January 2019 from Octane Press.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

There was plenty of professional racing going on in the world by the late 1950s. Outside of the U.S., international racing was governed by the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). Some Americans like Phil Hill, Dan Gurney and Carroll Shelby achieved professional status by racing in Europe against the best drivers of the day, but for most drivers in the U.S. racing for money risked the loss of their SCCA licenses.

Bringing international caliber drivers to the U.S. became an obsession for early race organizers like Bill France Sr., the founder of NASCAR, and the leaders of the FIA correspondingly saw the U.S. market as a huge opportunity. With the withdrawal of the AAA from race sanctioning in 1955, representatives from the FIA came to America in 1956 with the intention of hitching their wagon to one of the established sanctioning bodies already functioning in the U.S.: NASCAR, USAC and the SCCA.

The emissaries from Europe met with France Sr., Colonel Arthur Harrington, former president of the AAA Contest Board and one of the founders of USAC, and Jim Kimberley, who represented the SCCA. The leadership at USAC saw this as an enormous opportunity to take control of professional road racing if they could convince the FIA representatives to give them their seal of approval. But France Sr. had other ideas. He understood that if just one organization owned the FIA relationship, it would quickly put the others at a disadvantage. He instead proposed a committee comprised of all three sanctioning organizations, each with the ability to apply for the FIA’s international listings for their events. The FIA agreed and the Automobile Competition Committee of the United States (ACCUS) was formed in 1957. ACCUS continues to operate today as the representative of American racing to the FIA, albeit with more member organizations.

Shortly after the creation of ACCUS, race organizers secured FIA listings for Formula One Grand Prix events at Sebring in 1959 and Riverside in 1960, running them under the FIA banner without a U.S. sanctioning body. These professional events were groundbreaking; they introduced world-class race drivers and their exotic machines to American audiences. By 1961, USAC had taken over the sanction of the L.A. Times Grand Prix and a similar event held at Laguna Seca.

The first Watkins Glen-based Formula One race was held in 1961 under direct FIA sanction. These races, along with Alec Ulmann’s 12 Hours of Sebring held in March, became a powerful magnet for American drivers who wanted in on the action.

Despite the success of these major events, SCCA races were still understood to be strictly amateur. Drivers began to bristle at the draconian restrictions being imposed on them by the Club. They wanted to compete at the next level of motorsport, test themselves against the best from the rest of the world and make some money along the way. But was the penalty for participation worth it?

In response, in the summer of 1961, the SCCA began to ease its restrictions on members participating in certain, designated professional events. But confusion reigned – it wasn’t clear which events were approved and which were not. Ultimately, after much hand-wringing, the Club’s Board once again withdrew public support for professional racing, leaving American drivers in limbo. Privately, however, the Board voted that summer to move forward with a plan that had been drawn up by John Bishop. It was a blueprint for professional racing that put a high priority on reclaiming the sanction of the most important races in the U.S. operating at the time: the 12 Hours of Sebring, The L.A. Times Grand Prix at Riverside, The U.S. Grand Prix at Wakins Glen, and the San Francisco Examiner Grand Prix at Laguna Seca.

Roger Penske on his way to winning the L.A. Times Grand Prix in the Zerex Special at Riverside International Raceway in 1962. The race was sanctioned that year by USAC. Photo credit: IMRRC Archives

USAC held six road racing events in1961 with limited support from SCCA drivers, although some did cross the line. The SCCA licenses for these transgressors were promptly revoked, further fanning the flames of discontent. But the door had been cracked open and it was now just a matter of time before professional racing became a reality at the Club.

There was mass confusion during the 1962 season as USAC and the SCCA sparred over dates, rules and drivers. In the December 1962 issue of Sports Car magazine, the Club announced the formation of the United States Road Racing Championship (USRRC) to be run the next year in classes of cars with engines over 2.0 liters and under 2.0 liters. This was the Club’s first openly professional series, starting with the Daytona Continental in January of 1963.

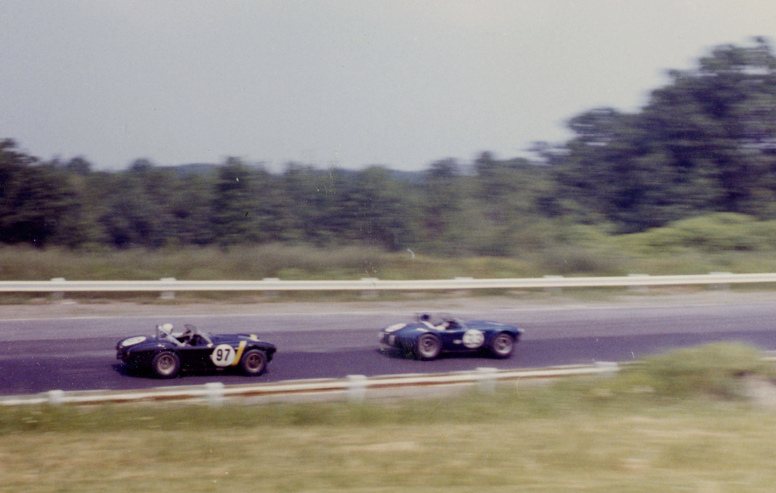

Bob Johnson leads Dave MacDonald during the 1963 USRRC event at Watkins Glen. Both are driving Shelby Cobras, a mainstay of the series in its first year. Photo credit: IMRRC Archives

With full FIA listings and open invitations to professional drivers from both the U.S. and Europe, the USRRC quickly became the go-to sports car racing series in the country. Support for USAC’s road racing events withered, never to return. Over the next two years, the SCCA took over the sanction of the L.A. Times Grand Prix, the San Francisco Examiner Grand Prix at Laguna Seca, the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen and the 12 Hours of Sebring. SCCA drivers that had been patiently sitting on the fence were now able to put both feet in with the new series.

The start of the USRRC race at Watkins Glen in 1964. Photo credit: Ozzie Lyons/© Pete Lyons at petelyons.com

The SCCA quickly followed up the USRRC success with the Can-Am, Trans-Am and Formula 5000 series, further cementing its status as the sanctioning body with the most competitive professional road racing circuits in the U.S. by the late 1960s.

The Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) was founded in 1944 by a group of wealthy sports car enthusiasts from Boston as a kind of gentleman’s club, according to Peter Hylton, SCCA archivist and historian. The original members were all friends that shared the same economic status and liked cars, the more exotic the better. Joining was not easy. Prospective members of the SCCA had to be formally endorsed by an existing member and voted into the Club by the rest of the membership.

Those first meetings consisted of shared meals and conversation followed by rallies on public roads. Soon, the footprint of the SCCA began to grow as it began to sanction races over fixed courses on public roads. The Club expanded westward and southward by formally chartering regional chapters. But even as the Club grew, it always adhered to the notion that racing was strictly an amateur activity and for Club members only.

By 1955, the SCCA had become the sports car road racing alternative to the American Automobile Association (AAA), which sanctioned champ car, sprint car and midget racing on ovals and to the National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR), which ran stock car races in the South and through alliances with promoters in the Northeast, Midwest and on the West Coast. In many respects, the early success of the SCCA reflected the post-war economic boom. As the economy grew, so did the ranks of the middle class. New prosperity brought increased interest in European sports cars like MGs, Jaguars, Porsches, Ferraris, Alfa Romeos, and others. And once these cars were on the street, competition was inevitable.

Racing through the streets of Watkins Glen began in 1948 and Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin in 1950, but racing on public roads was deemed too dangerous after a spectator fatality at Watkins Glen in 1952. Demand for road racing venues escalated quickly, but there were simply not enough purpose-built tracks at the time – building permanent race tracks was an expensive and slow process. The shortage was partly relieved with the help of Curtis LeMay, an Air Force General in charge of the Strategic Air Command (and car guy), who opened up a few decommissioned WWII airfields for racing events.

The 12 Hours of Sebring was held on a decommissioned B-17 training base south of Orlando, Florida starting in 1952. As this photo shows, the condition of the pit area had improved only slightly by 1957. Photo credit: IMRRC Archive

Mike Hawthorne in a D-Type Jaguar during the 12 Hours of Sebring held in 1955, when the race was sanctioned by the AAA. After the debacle at Le Mans later that year, Alec and Mary Ulmann formed the Automobile Racing Club of Florida (ARCF) as an entity to produce and promote the race. The SCCA took over sanction of the Sebring event in 1964. Photo credit: IMRRC Archive

The landscape changed dramatically and suddenly with the infamous disaster at Le Mans in 1955. Pierre Levegh, co-driving with American John Fitch, made contact with a slower car on the main straight, vaulting his Mercedes-Benz into the air, which struck a retaining wall and exploded, sending components into the crowd. Levegh and more than 80 spectators were killed. As a direct result of this horrific accident, the AAA decided to drop out of race sanctioning altogether. This left a void in the sanctioning world that was quickly filled by the newly formed United States Auto Club (USAC), organized at the behest of Indianapolis Motor Speedway owner Tony Hulman.

But rather than just focus just on the AAA’s former turf, USAC had bigger ambitions. It had designs on becoming the single dominant player in all forms of motor racing – short tracks, stock cars and road racing. Knowing the SCCA was committed to amateur racing, USAC announced a professional road racing series for 1958.

USAC ran its first road races at Lime Rock Park, Marlboro Motor Raceway and the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Circuit in 1958, which caught the attention of the top drivers of the day. The concept of racing for money instead of just trophies was enticing. The SCCA Board of Governors hotly debated whether to respond with the Club’s own professional series or to maintain strict, amateur-only status.

In the end, the Board decided to keep the status quo. But as part of this decision, the Board of Governors decreed that SCCA licensed drivers and corner workers who participated in, or assisted with, USAC events would be banished from the Club. Further, it was announced that any SCCA region participating in a racing event where remuneration was offered would have its charter revoked. This form of harsh excommunication was designed to keep the membership in line. Ultimately, this strategy failed, but a seven-year war for control of road racing in America had been formally declared.

TO BE CONTINUED…

After the end of World War II, sports car racing experienced a renaissance, unlike anything America had ever witnessed before. The post-war economy was booming. And when combined with a growing workforce of educated, skilled workers created by the G.I. Bill, it helped create a vibrant American middle class. For the first time since the Great Depression, families began to have money for more than just the basics, including sports cars, which were beginning to show up from exotic places such as Italy, Britain, Germany and other countries.

The small trickle of imported machines grew steadily and the inevitable happened – races started to emerge. This is the behind-the-scenes story of what happened next, how sports car racing emerged in America during the post-war era, who organized the races and the all-out war that erupted for control.

My father, John Bishop, started his career with the SCCA in 1956, at the very beginning of the knock-down fight between the SCCA and USAC over control of professional road racing in America. He later would take over as executive director of the SCCA at the beginning of 1962, putting him squarely in the middle of the drama. What follows is an account of that period, excerpted from the book: “IMSA 1969-1989: The Inside Story of How John Bishop Built the World’s Greatest Sports Car Racing Series,” authored by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, scheduled for publication in January 2019 from Octane Press.

-Mitch Bishop