The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of how IMSA got started and its first 20 glorious years. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

BMW of North America’s racing group was established in 1975 in an effort to support the company’s growth in the lucrative US performance car market. Unfortunately, the company did not have an IMSA championship to show for the investments in the BMW 3.0 CSL and the turbocharged BMW 320i. With just one or two cars pitted against a host of Porsches, the odds were not in their favor. The tube frame M-1 Procar did crush the GTO competition in 1981 but was underpowered in IMSA’s top GT Prototype (GTP) class.

Something had to be done to narrow the gap. Former SCCA executive Jim Patterson, who took over the BMW North America racing program in 1978, saw the newly minted IMSA GTP rules in 1980 as a way to get back in the game. Working with partner March Engineering, a unique new prototype was unveiled in early 1981 that would become the basis for a long, successful supply of GTP cars to the IMSA field from the British company.

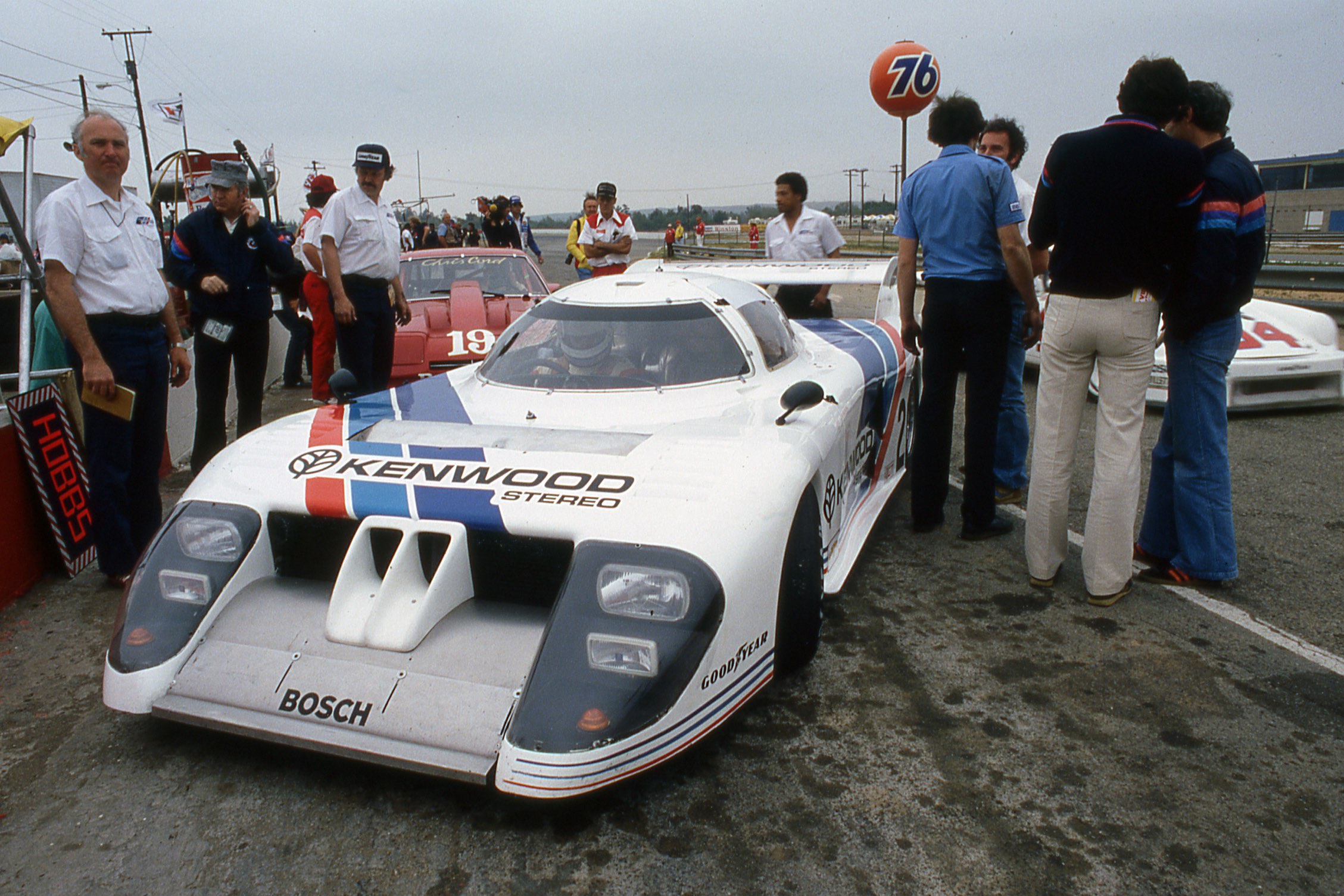

The BMW M1/C debuted at Riverside in April 1981. The March chassis featured a modern aluminum monocoque that was mated to a normally aspirated 3.5-liter BMW engine. The team would upgrade to a 2.0-liter turbocharged motor later in the year. Photo: Don Hodgdon

Designed by French aerodynamics expert Max Sardou and BMW engineer Raine Bratenstein, the car was dubbed the BMW M-1/C. It was built around a March Engineering aluminum monocoque and featured two distinctive pontoons at the front that were designed to channel airflow to both the radiators and twin ground-effects tunnels for maximum downforce. The car was initially fitted with a 3.5-liter, six-cylinder, normally aspirated BMW engine, and entered for the first time at the Riverside 6 Hours in April 1981 with David Hobbs and European endurance veteran Marc Surer at the wheel. Featuring sponsorship livery from Kenwood audio, the pair finished a credible sixth place, albeit eleven laps down to the winning 935 piloted by Fitzpatrick and Busby.

The lone BMW M1/C is swamped by a host of Porsche 935s at the start of the 1981 Riverside Camel GT race. The M1/C would go on to finish sixth, eleven laps down from the winning Porsche 935 of John Fitzpatrick/Jim Busby (#1). Photo: Don Hodgdon

A week later at Laguna Seca, Hobbs placed sixth again, this time one lap down to the new Lola T-600 with Brian Redman at the wheel. Although down on power, Hobbs managed to put the car on the front row at both Lime Rock and Mid-Ohio. The first few races proved the M-1/C had real potential and the decision was made to further develop the chassis and engine. The long-term plan was to install the 1.5-liter turbocharged BMW motor being developed for Formula One, but that engine wasn’t ready and would never be used in the March. Instead, the team force-fit the same turbocharged 2.0-liter, four-cylinder engine that had been used successfully in the McLaren-engineered BMW 320i program. Since the M-1/C had not been designed for that power plant, it required a cooling workaround for a motor that produced 600 to 675bhp with the boost turned up.

Results were mixed after the change. The new engine debuted at Sears Point in August. The car was fast and competitive, but ultimately unreliable. A fourth place at Portland would turn out to be the team’s best finish. Despite stating long-term commitments early on, BMW again left IMSA racing at the end of the year, this time to focus on its Formula One program.

Even with this setback, March Engineering took what it had learned from the M-1/C experience and produced a viable, stable GTP customer car for 1982, dubbed the 82G, that was designed by Gordon Coppuck. The first two customer March 82Gs appeared in January for the 24 Hours of Daytona. One of them was a Chevrolet V8-powered version driven by Bobby Rahal and Jim Trueman and fielded by Garretson Enterprises. Rahal would campaign the car in later rounds with Michelob backing.

The first March 82G customer car was fielded by the Garretson team at Daytona in January 1982. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

The other March was campaigned by Dave Cowart and Kenper Miller’s Red Lobster team. After winning the 1981 GTO championship in the dominant BMW M-1, the team commissioned an 82G from the March factory with the now well-tested 3.5-liter BMW M-1 engine. The distinctive twin pontoons of the March turned out to be a perfect canvas for two Red Lobster claws, a design that became iconic almost instantly. Unfortunately, the normally aspirated BMW engine was no match for the Chevy V8 or Porsche 935s, and for 1983 the team campaigned with Porsche 935 turbo power, only to suffer from overheating issues. The team took the midsummer Daytona race off in 1983 and came back later in the year with Holbert’s second March 83G powered by a Chevy V8.

The twin pontoons of the March 82/3G were ideally suited for the paint scheme of the Red Lobster team, pictured here in 1983 at Daytona, leading the similar Porsche-powered March of Al Holbert. Photo: Richard Bryant

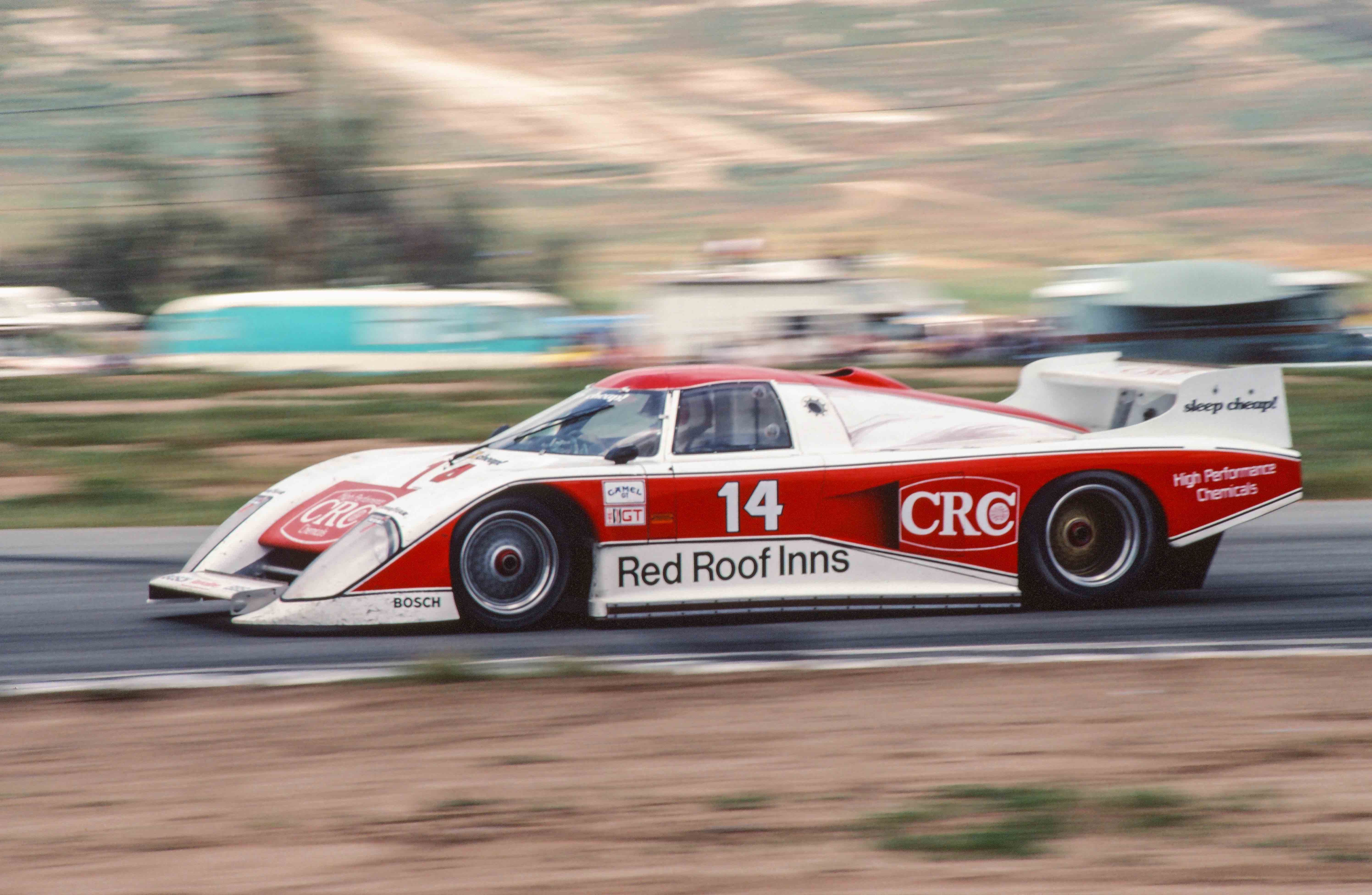

The biggest news of the 1983 season was the return of Al Holbert, who had been pursuing Indy Car and Can-Am glory. Holbert started the season by sharing Bruce Leven’s Bayside Disposal 935 with Hurley Haywood at Daytona and Sebring. But his main focus was on a CRC Chemicals–sponsored March 83G, initially fitted with a small-block Chevy V8. Holbert won with the car the first time it was entered, at the inaugural, but rain shortened, Grand Prix of Miami. After skipping the Road Atlanta round, Holbert finished second at Riverside and won Laguna Seca, after which he sold the car to Kenper Miller and Dave Cowart’s Red Lobster team.

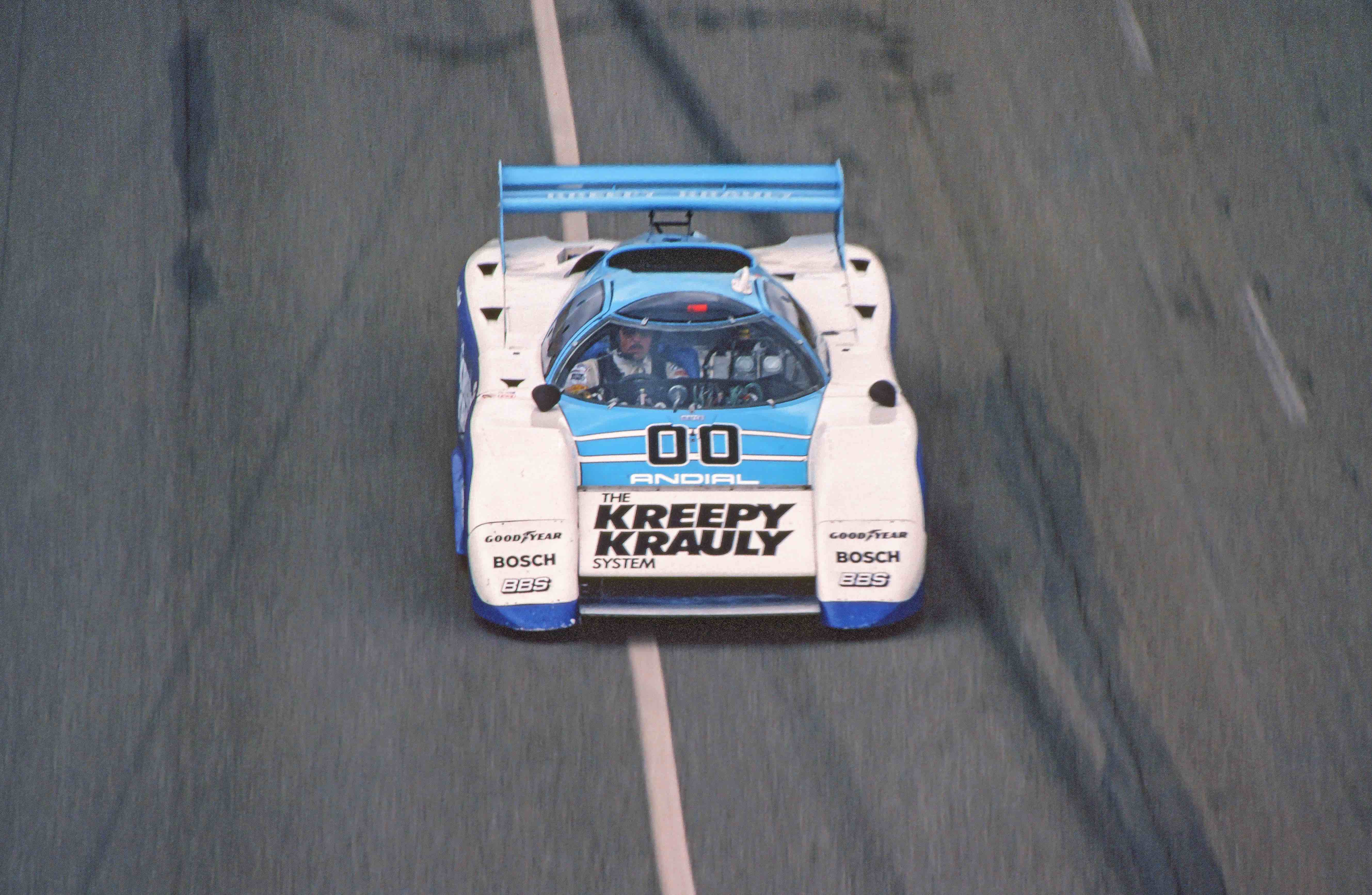

Holbert had another ace up his sleeve: a brand-new March 83G, this time fitted with an ANDIAL-prepared Porsche 934 single-turbo engine. Despite skipping the Mid-Ohio and mid-summer Daytona events, Holbert easily took the 1983 Camel GT title by winning with the new Porsche-powered car four times and scoring points in another seven races.

Al Holbert’s triumphant return to IMSA competition in 1983 came at the wheel of a March 83G fitted with small block Chevy V8, shown here at Riverside. He later switched to a new March 83G chassis fitted with a single turbo Porsche 934 motor and won the 1983 Camel GT championship. Photo: Kurt Oblinger

One of the prettiest GTP cars of the era, the ex-Holbert Racing Porsche-powered Kreepy Krauly March 83G of Sarel Van der Merwe, Tony Martin, and Graham Duxbury, won the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1984, pictured here at Riverside in the 1984 season. Photo: Kurt Oblinger

The Blue Thunder Marches of Bill Whittington and Randy Lanier, sponsored by Apache Powerboats, dominated the 1984 Camel GT season with six wins, including one here at Watkins Glen, giving the title to Lanier. Photo: Whit Bazemore

With the introduction of the Porsche 962 into the Camel GT Series in 1984, it wouldn’t take long for Porsche to once again dominate U.S. sports car racing. The 1984 championship in the hands of Randy Lanier driving a Chevy-March would turn out to be the last for a March-based car in the series. But not without a fight.

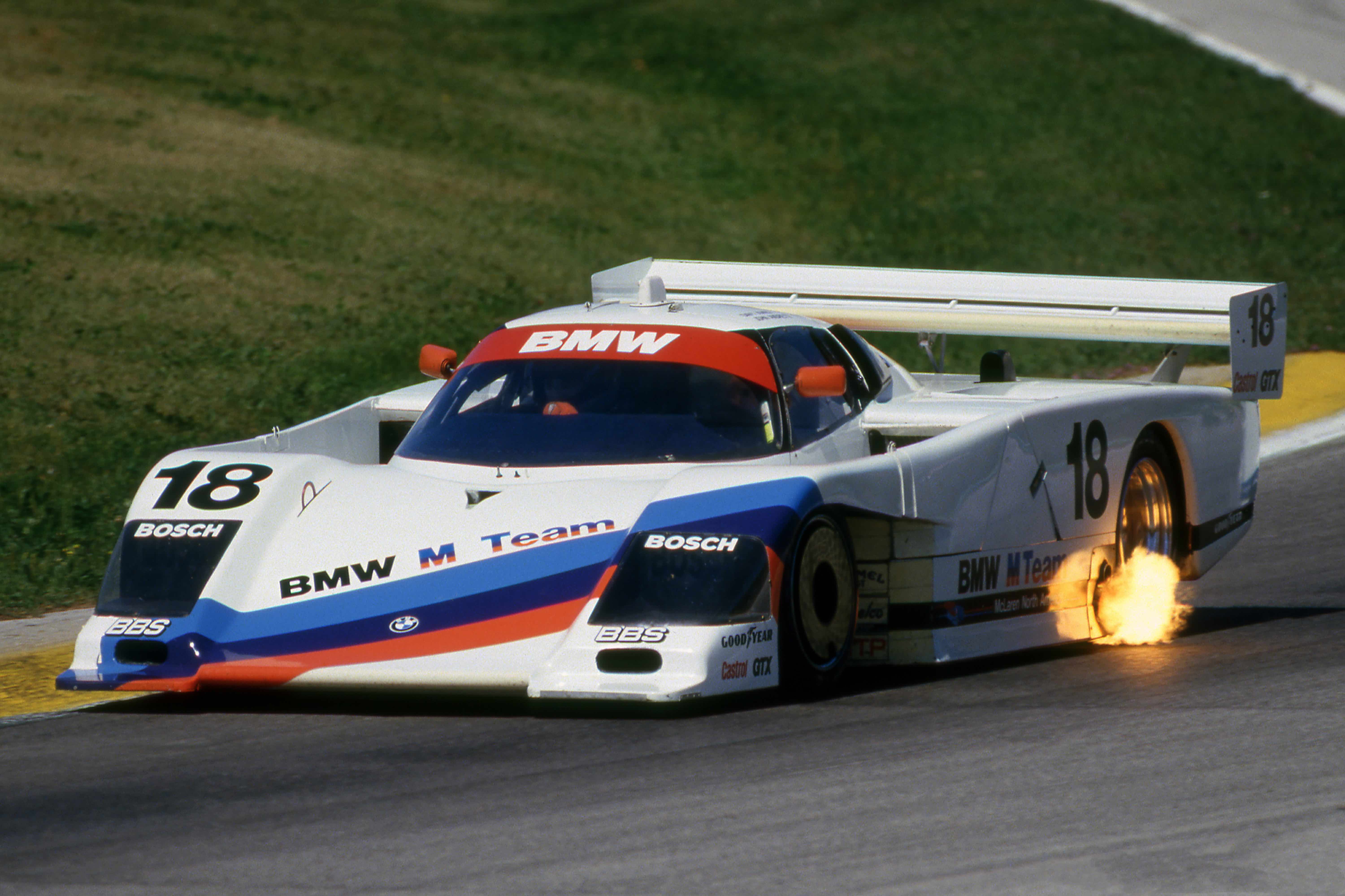

BMW decided to renew its Camel GT program by entering a March 86G chassis for David Hobbs and John Watson in the 1985 season-ending race at Daytona. As before with the 320i program, McLaren North America prepared the cars and ran the team. By this time, BMW’s 1.5-liter turbocharged Formula One engine was well developed and reliable. It was the same engine used by Nelson Piquet to secure the 1983 Formula One World Championship. It was adapted in a 2.0-liter form for the March 86G, the first prototype designed entirely using computer-aided design equipment. Power output was a reputed 1,100bhp with the boost turned up.

A second car for John Andretti and Davy Jones was built early in 1986, but during testing at Road Atlanta, it was destroyed in a fire caused by a fuel line that had been loosened by an engine vibration. The same vibration caused a serious, end-over-end crash in practice at Sebring when the rear cowling flew off, destroying a second tub, and forcing the team to withdraw.

Given the teething issues and destroyed cars, Bob Riley and a host of all-stars were brought in to help sort things out. After working flat out, the team turned the BMW-March into a very fast but still inconsistent car. The team skipped a few races during the 1986 season, but the car’s outright speed was evident whenever it showed up. After winning the pole at Road America, Jones survived a horrific high-speed crash in the race just after the kink in the backstretch when he put two wheels off in the grass on driver’s left. Bad luck and mistakes seemed to dog the team.

The BMW March 86G was a generation ahead of the rest in terms of aerodynamic grip and raw speed in 1986. Reliability issues kept it from doing well much of the season. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

However, the team’s triumphant moment arrived in one spectacular win at Watkins Glen with Andretti and Jones at the wheel. The two BMWs started on the front row and the winning car lapped almost everyone else in the field. In spite of the promising result and the car getting faster without direct factory support from Germany, BMW once again withdrew from IMSA after the Daytona finale at the end of 1986. David Hobbs lamented the decision, saying, “We could have cleaned the table with that car in 1987, it was probably the fastest prototype I ever drove.” Two of the March 86G chassis were sold to Gianpiero Moretti, who installed Buick V6s (one was a turbocharged 3.0-liter and another was a 4.5-liter normally aspirated motor) and raced them the following year.

The BMW March team scored its most impressive weekend at Watkins Glen, with both cars on the front row and John Andretti/Davy Jones taking the overall win in convincing fashion. Photo: Tony Mezzacca

When BMW canceled its IMSA GTP program at the end of 1986, Gianpiero Moretti purchased the March 86G chassis and installed turbo-powered Buicks for the 1987 season. He co-drove here at Sears Point with Whitney Ganz. Photo: Richard Bryant

Organized races through the village of Watkins Glen and surrounding roads were started by Cameron Argetsinger in 1948, marking the beginning of post-war sports car racing in this country. Crowds grew steadily in the years that followed. But it was the 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix weekend, during the running of the main Grand Prix race, when a tragic accident occurred at the beginning of the second lap that changed everything.

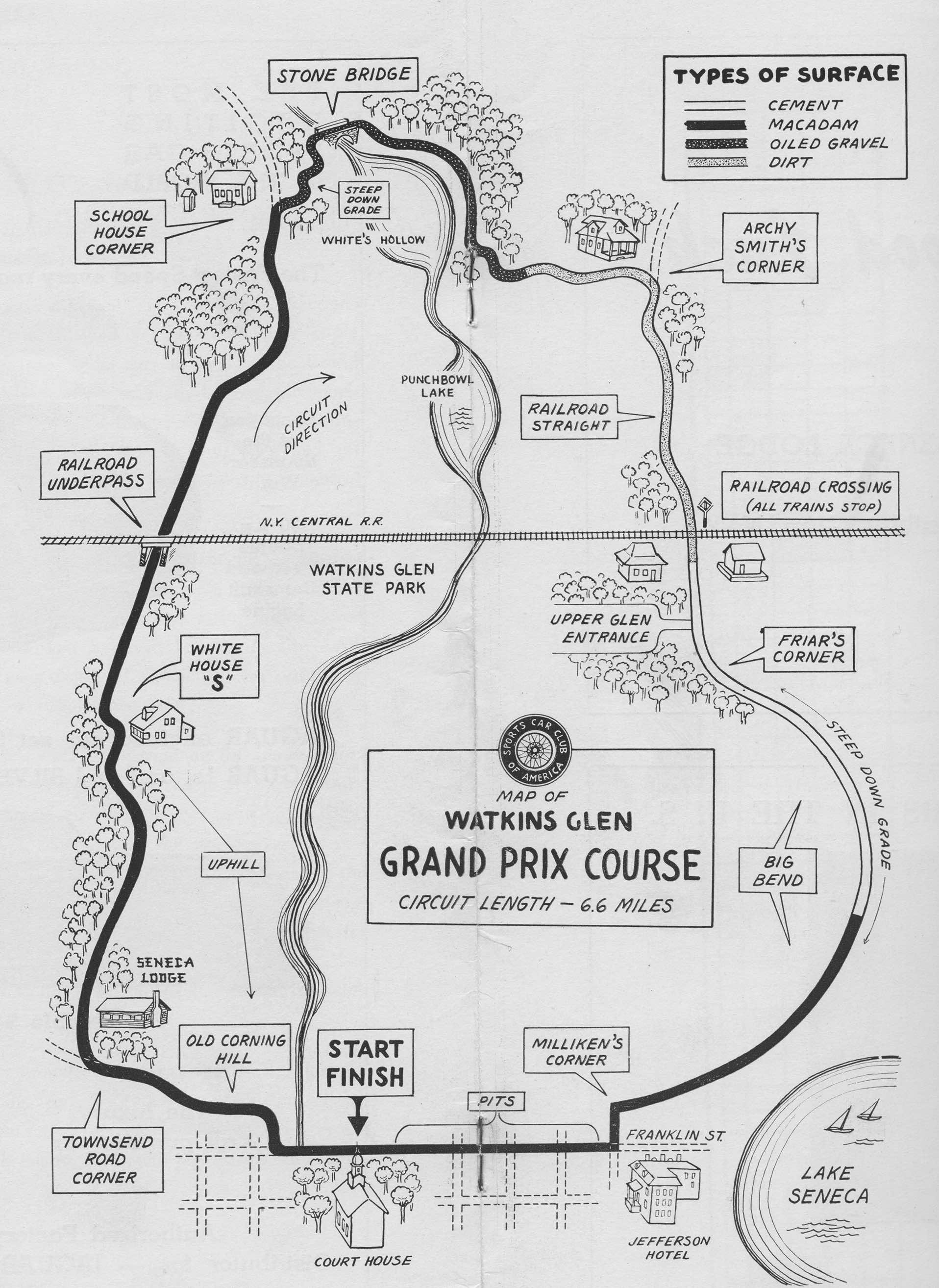

The original 6.6 mile Watkins Glen circuit utilized the main road through town, Franklin Street, as the front straight. The rest of the layout wound its way through the hills above town. Source: International Motor Racing Research Center

Fred Wacker, driving a Cadillac-Allard, attempted to pass second place John Fitch at the wheel of a Cunningham on the approach to the first turn, directly across from the main entrance of Watkins Glen State Park. Wacker brushed the crowd, injuring 12 spectators and killing a seven-year-old boy. This area of the track was designated as a no passing zone and a no spectator zone. Throughout the day police repeatedly chased spectators out of the location, but with a large crowd on hand that year it was impossible for them to keep full control of the excited swarms of spectators. After the accident, the race was stopped, never to be finished.

Because of the accident, road racing at Watkins Glen was at a crossroads in the late fall of 1952 and the early months of 1953. A short time after the September race, a public meeting was held to determine if the community would hold more races on the existing circuit or find a new circuit within Schuyler County. The general feeling was that a new, safer course should be found.

In its January 1953 session, the New York State Legislature considered two proposed laws to ban racing on public roads. One bill was passed in the Senate but never made it out of committee in the Assembly. Thus, there was never a law enacted to ban racing on public roads in New York State. What the State actually did was withhold issuing of permits for racing on state roads – dooming the use of the original 6.6-mile circuit at Watkins Glen, which was made up of more than 85% state roads. In addition, Lloyds of London, the insurer, refused coverage of the race if it ran through downtown Watkins Glen.

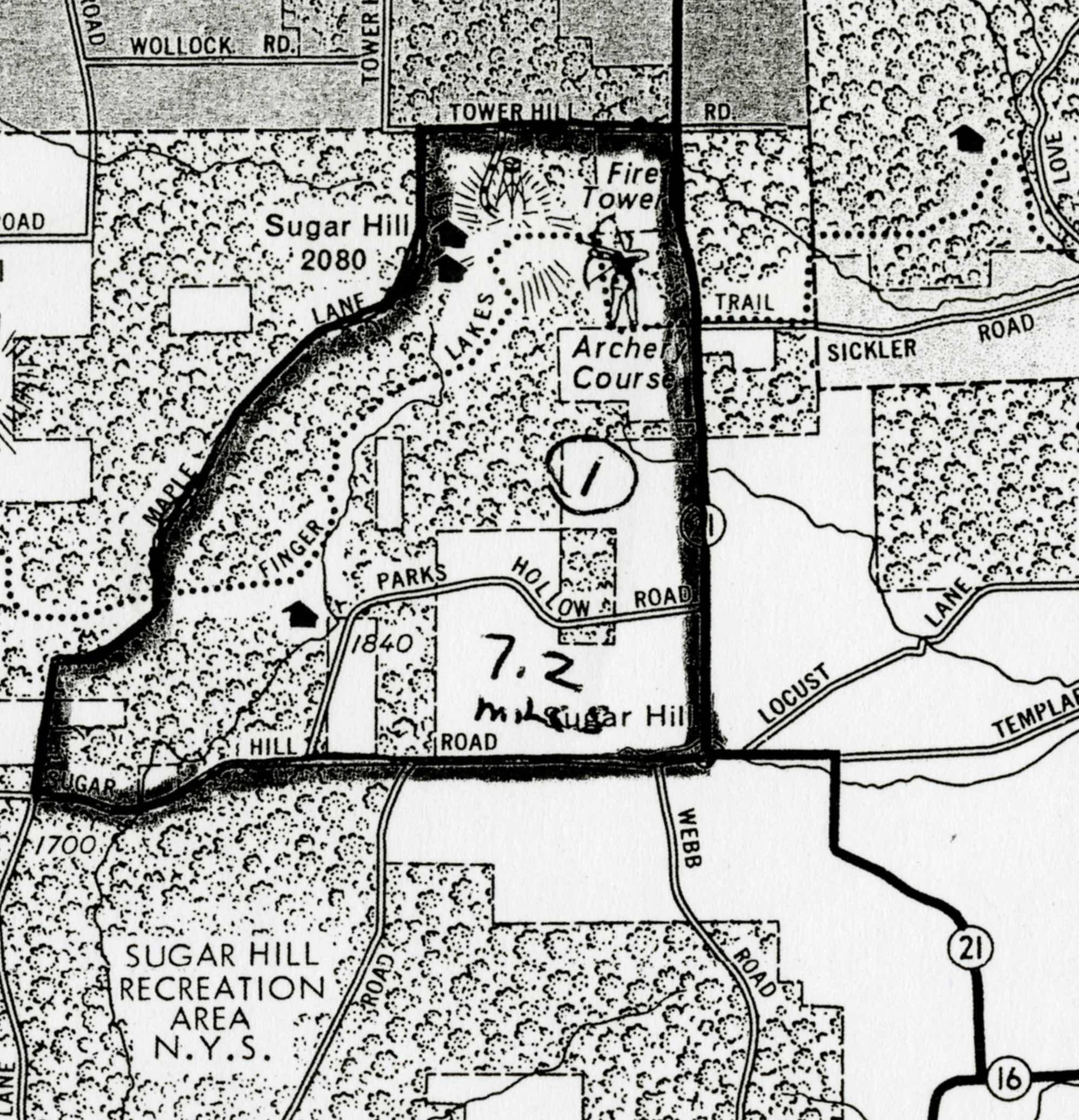

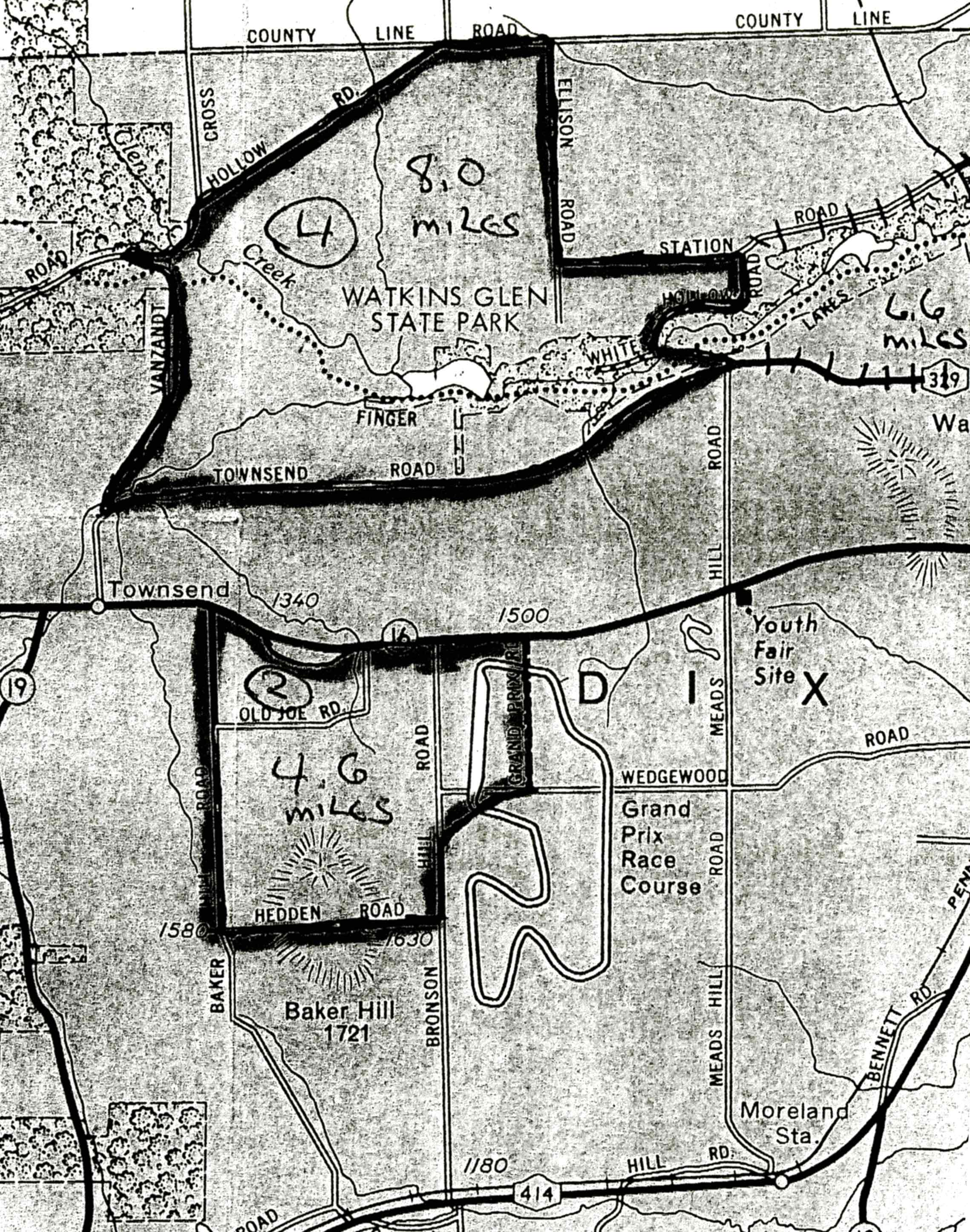

The Race Committee, empowered to make the selection of a new circuit, consisted of representatives of the community: Chamber of Commerce President Don Brubaker; Grand Prix founder Cameron Argetsinger; attorney Henry Valent; proprietor of Smalley’s Garage Lester Smalley; Watkins Glen Mayor Allen D. Erway; Schuyler County Highway Superintendent Ernest Porter; 1952 Grand Prix Chairman George Shannon; attorney Liston Coon; long-time member of the Chamber of Commerce Leon Grosjean; trainmaster for the New York Central Railroad (“the man who stopped the trains”) Frank Chase; and reporter for the Elmira Star-Gazette Arthur H. Richards, Jr. They considered five potential sites for the circuit: a 7.2 mile layout in the Town of Orange; two in the Town of Dix – one 8.0 miles and the other 4.6 miles; and, two circuits on east side of Seneca Lake – a 4.8 miles layout in the Town of Hector and a 6.7 miles layout in the Town of Montour (which overlapped in part the Hector circuit). Both the Hector and Montour layouts ran under the Lehigh Valley Railroad underpass at the Dolphsburg Road corner before making a right turn.

Most of the roads proposed for use as a replacement circuit were made up of county and town roads which were narrow and had little hard-top surface. They were largely gravel surfaces and the circuit selected would require widening and paving.

The 7.2 mile “Brigham Young” circuit layout was one of two race course sites considered by the Watkins Glen Race Committee following the disastrous 1952 Grand Prix through the streets of the town. Source: International Motor Racing Research Center

The Committee settled on two possible race course sites. One was a 7.2-mile course in the Town of Orange (called the Brigham Young Circuit) which would have run through the small hamlet of Sugar Hill. The second was a 4.6-mile course (called the Jane Delano Circuit) in the Town of Dix near the hamlet of Townsend.

Before the work was to start, the Committee asked James Lamb, Contest Board Secretary for the American Automobile Association (AAA), which then sanctioned sports car racing in the U.S., to tour the circuits and offer an assessment. He reported favorably on the circuits but was concerned that the road work could not be completed in time for the September 18-19, 1953 race date.

The 4.6 mile “Jane Delano” circuit layout through the town of Dix (bottom) became the home of the Watkins Glen races from 1953-1955 until the current track (illustrated to the right of the Jane Delano layout) was built on the hill above town. Source: International Motor Racing Research Center

The Town of Orange circuit ran through a section of the New York State Forest. The State Department of Conservation was uncooperative, fearing that spectators would cut down small trees for use in campfires during the race weekend which would lead to forest fires. For this reason, the proposed “Brigham Young” circuit was ruled out and the Town of Dix “Jane Delano” circuit was selected as the Watkins Glen Grand Prix venue.

After meeting with the Town of Dix Board, the race organizers were given permission to make use of town-maintained roads. A short time later, SCCA representatives, unable to make a complete tour of the proposed 4.6-mile circuit because of road conditions, decided they would not sanction the 1953 Grand Prix.

On July 15, the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation was formally organized and chartered. The organization originally consisted of seven directors appointed by the Watkins Glen Chamber of Commerce. The Grand Prix Corporation soon issued bonds in the form of “Six-percent Certificates of Indebtedness” in the sums of $100, $500 and $1,000. The Corporation leased all the grounds surrounding new circuit, entitling them to the exclusive and complete jurisdiction of the leased properties. In exchange, landowners received one-third of the profits from the event, with the remaining thirds shared equally by the Community Chest and the Grand Prix Corporation.

Bill Milliken and George Weaver were consulted regarding road work and related engineering considerations. Work started on August 2 with the construction firm of Martin & Son of Burdett, New York as the general contractor. All around the course trees, hedges and brush were removed and utility poles and fences were relocated. The road was widened to 28 feet and the shoulders extended to four feet on each side of the road. Extensive grading, ditching and culvert work was also required. Remarkably, on August 19, one month before the race, work was finished and the course was half completed. The remaining half, laying the asphalt, was undertaken by the Watkins Glen firms of Harry Suits and Franzese Brothers. Completed on September 9, the track was ready for the race on time.

It was decided that no spectators would be permitted inside the track or within 30 feet of the track. Spectators were not allowed to drive on the actual course to reach the designated parking areas at any time during the race weekend. RCA race safety systems and public address systems were installed around the circuit.

General admission for the races was $1.25, grandstand seats ranged from $3.00 to $5.00, and parking was $1.00 per car. For the first time in the Glen’s history, Friday prior to race weekend was used for official practice.

On Saturday morning, the first race of the day was the Seneca Cup, an 11 lap (50.6-mile) event, with 19 starters. The race was won by Dr. M.R.J. Wyllie driving a Jaguar XK120M, with Wyllie moving out on the shoulder to pass Phil Cade’s Grand Prix Maserati R1 in the final turn of the last lap, winning by less than 100 yards. He averaged 72.1 mph.

Later the same day, twenty-nine cars took the green flag in the Queen Catharine Cup, a 22 laps or 101.2 miles race. George Moffet claimed the victory, driving an OSCA with an average speed of 73.7 mph.

Looking back at the last turn before Start-Finish line at the1953 Watkins Glen Grand Prix, the #90 Jaguar XK-120 of Gled Derujinski leads the Siata of Otto Linton (#58) and the Jaguar XJ-120 of George J. Constantine (#49). Source: William Green Motor Racing Library/International Motor Racing Research Center

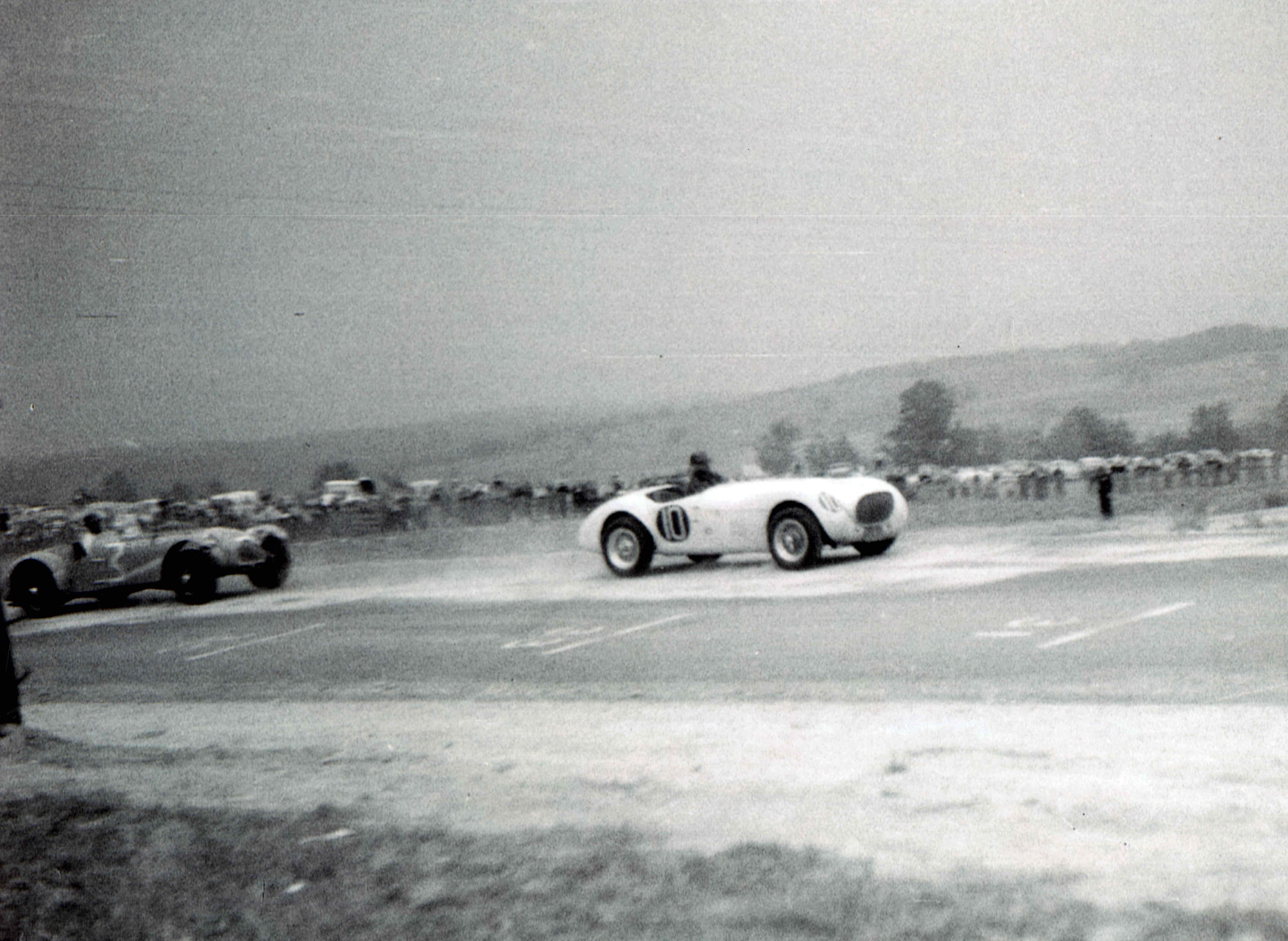

The last race of the day was the 6th Annual Watkins Glen Grand Prix, a 22 laps (101.2-mile) event with 27 cars starting. The Grand Prix featured a race-long duel between Walt Hansgen driving the Hansgen Jaguar Special and George Harris in a Cadillac-Allard. The lead changed hands four times on the last lap, with Hansgen winning by a scant 1.1 seconds at an average speed of 76.1 mph.

The 1953 Watkins Glen Grand Prix, at the last turn of the last lap. The Hansgen Jaguar Special of Walt Hansgen (#10) leads the Cadillac-Allard of George Harris (#3) across the line for the win. Source: William Green Motor Racing Library/International Motor Racing Research Center

The race on the new circuit was judged a huge success in the local press, with crowd estimates ranging from 20,000 to 60,000. The next two years’ races were sanctioned SCCA national events and run on the same circuit. Today, parts of the 1953-1955 circuit run through the current racecourse at Watkins Glen International, built in 1956 and substantially rebuilt in 1971.

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

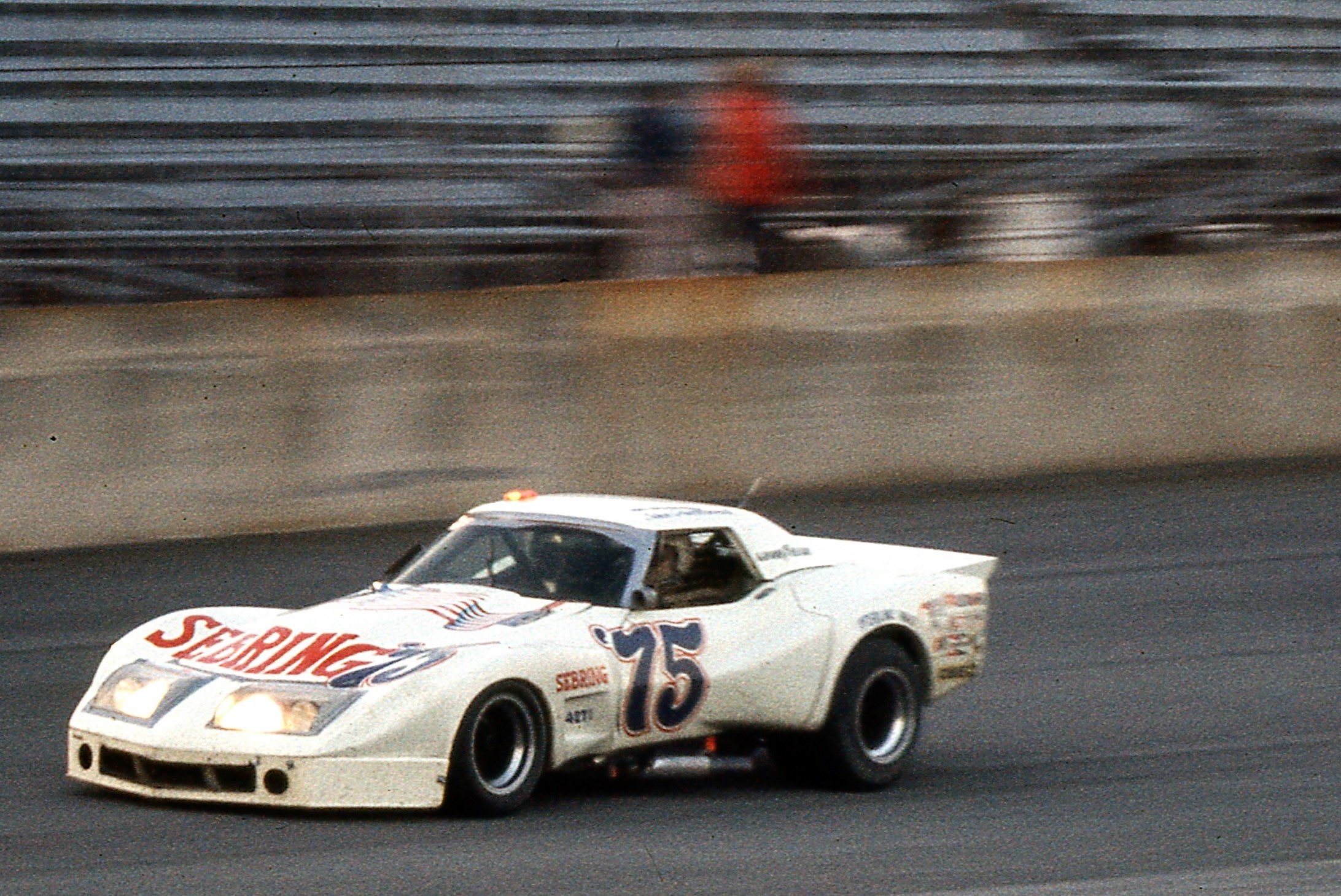

John Greenwood’s Corvette under braking for turn one during the 1975 24 Hours of Daytona, featuring his paint scheme promoting the 12 Hours of Sebring a few weeks later. Photo: Mark Raffauf

After a troublesome start at Daytona and subsequent upgrades to the car, the two-car factory BMW team showed up for the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1975 ready to mix it up. Australian touring car ace Alan Moffat supplemented the potent team of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Ronnie Peterson. The CSLs were now much improved and took advantage of specially crafted Dunlop tires. The old 5.2-mile Sebring course was a wide-open, hang-on-and-get-after-it circuit, where turns one and two were big, sweeping curves of concrete runway that required tremendous skill to navigate quickly without going off and hitting anything, including parked airplanes.

GT cars make their way down the massive back straight at Sebring in 1975. The runways of Sebring weren’t always as well marked as they are today. Nighttime navigation of the track was especially challenging. Photo: Mark Raffauf

In spite of John Greenwood’s Corvette taking pole, the BMWs stormed into an early lead. Within the first hour, Hans Stuck’s BMW was reported numerous times by corner workers at various locations not to have working brake lights. IMSA black-flagged the car to have its lights checked. Once in the pits, it was determined the lights were indeed working. A short time later the same reports started coming in: no brake lights, especially in turns one and two. The car was brought back in for another check. Again, all was good while stationary in the pits.

The winning factory BMW CSL of Hans Stuck, Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Allan Moffat navigates the wide-open runways of Sebring in 1975 when Lockheed Constellations and Douglas DC-4s lined the course unprotected between turns one and two. Photo: Mark Raffauf

When the issue arose a third time, BMW team chief Jochen Neerpasch asked IMSA officials, “Where are the lights not working?” to which race control replied, “Various locations, including turns one and two.” Neerpasch responded with, “Oh, Hans does not use the brakes there at all!” With the stickier tires and improved performance, GT cars were now able to take turns one and two flat, or at least with a slight lift instead of braking. No one had ever seen that before, hence the confusion from the corner workers and race control.

The winners of the 1975 12 Hours of Sebring celebrate in Victory Lane. Sam Posey stands on top of the BMW CSL, flanked by Brian Redman (far right), Hans Stuck (seated next to Redman) and Allan Moffat (with daughter). Photo: Bill Oursler/autosportsltd.com

In 1905, Caspar Whitney, a co-founder of Outing magazine and one of the creators of collegiate football’s All-American Team, named Yale as the season’s “national champion” in college football. Four years previously, The (New York) Sun had named Harvard as the 1901 collegiate football champions. Although the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was established in 1906, it first named national champions only in 1921, starting with track and field. Despite naming national champions in literally dozens of intercollegiate sports since then, the NCAA has not and still does not name a national champion in what is now the Football Bowl Subdivision, formerly known as Division I or Division I-A Football: it merely recognizes or accepts the decision of the College Football Playoff committee.

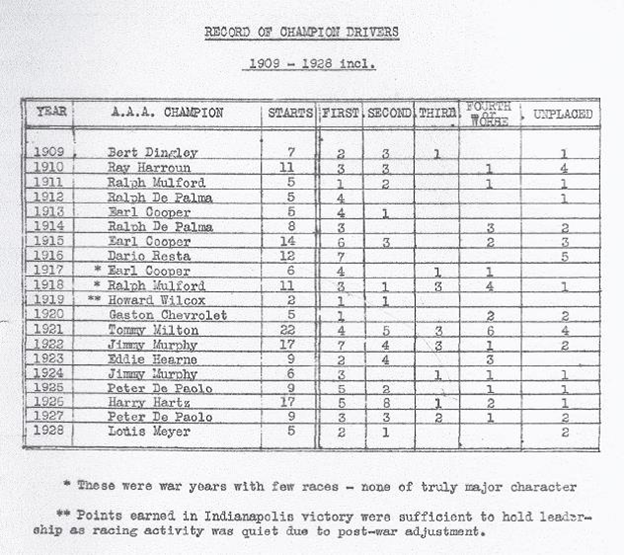

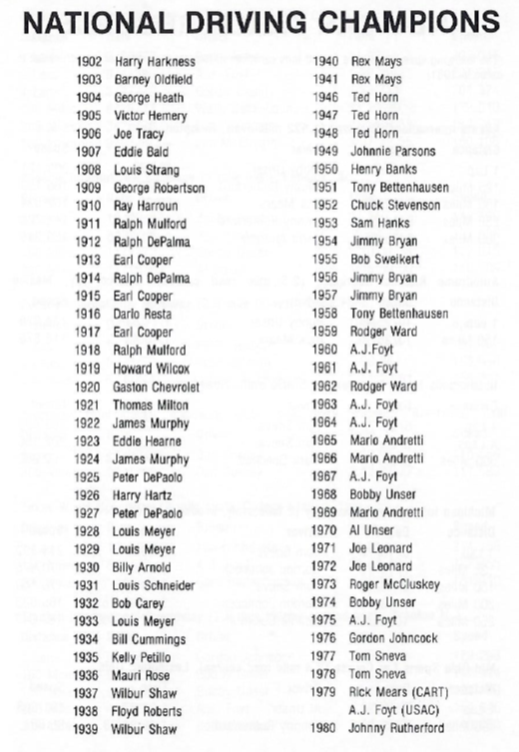

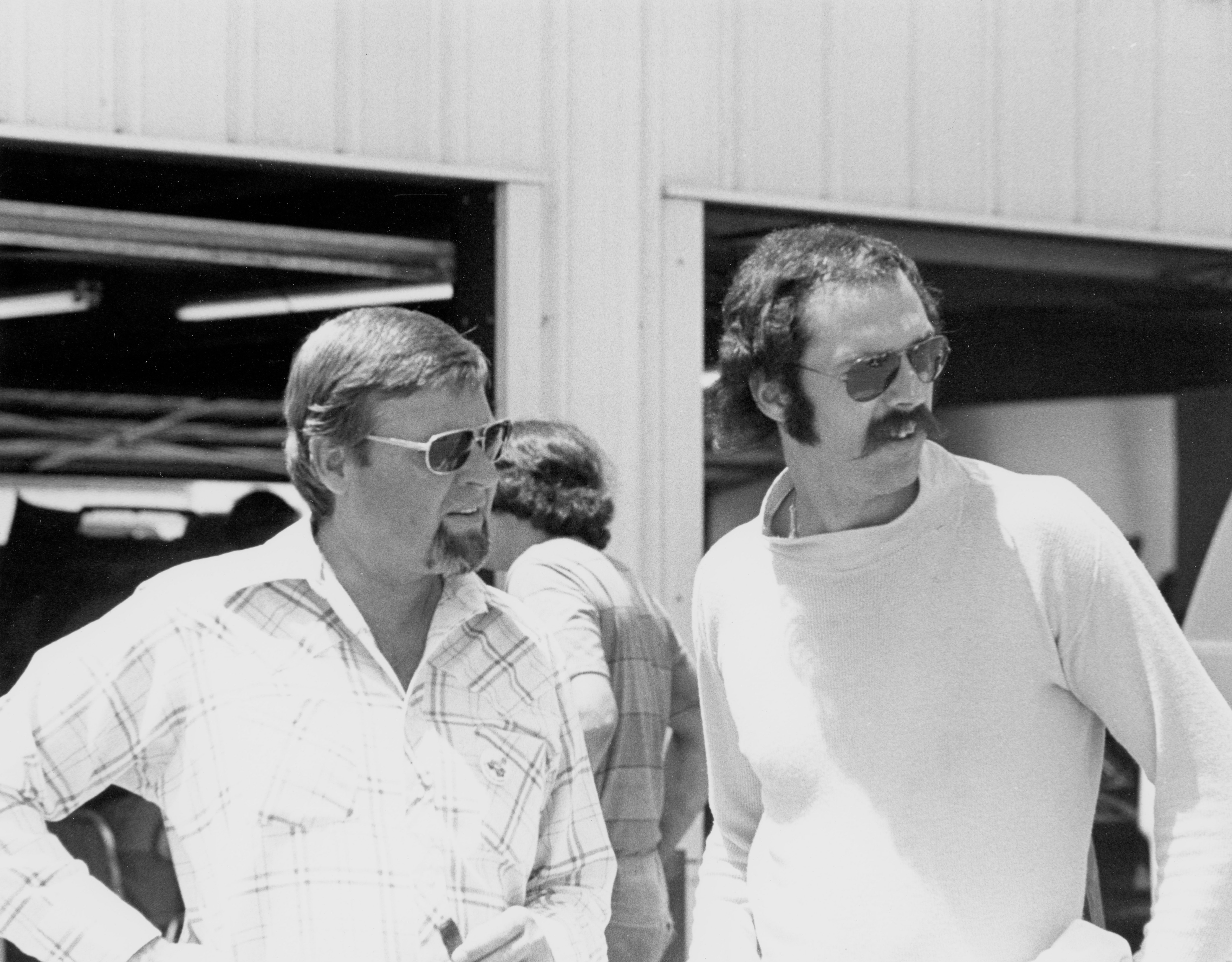

The listing of champion drivers that appeared in the 8 February 1929 bulletin issued by the AAA Contest Board. It is the first publication of the listing of champion drivers by the AAA beginning with the 1909 season.

This, of course, has not stopped those in the sports world from naming national champions in collegiate football. Beginning with The Sun and Caspar Whitney at the turn of the 20th Century, roughly three dozen systems have endeavored to select the national champion in collegiate football. Several of these have used statistical data to retroactively select national champions all the way back to the very first season for collegiate football in the United States, 1869. In 1926, professor Frank Dickinson, of the economics department at the University of Illinois, created what seems to be the first mathematical system to determine the national championship, with the nod going to Stanford. The system devised by Dickinson attracted the interest of the coach at Notre Dame, Knute Rockne, who persuade the professor to apply the model to several previous seasons, with the result of Notre Dame becoming the retroactive 1924 national champion and Dartmouth the 1925 champion.

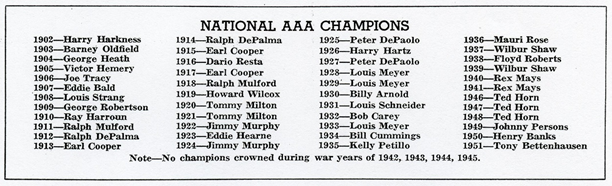

In the program for the 1952 500-mile race at Indianapolis, in an article written by Russ Catlin, this listing of AAA champion drivers appeared. Rather than 1909, the list begins with 1902, Bert Dingley is replaced by George Robertson for the 1909 season, and Tommy Milton replaces Gaston Chevrolet as the 1920 champion driver.

According to the listing of national championships provided by the NCAA, there are five colleges with claims to the national title for the 1926 season. The first is Alabama, with nine systems ranking it as the national champion: the Berryman (QPRS) System, which began in 1990; the Billingsley Report, 1970; the College Football Researchers Association, 1982 and 2009; Helms Athletic Foundation, 1941; National Championship Foundation, 1980; and, the Poling System, 1935. The school with the second highest number of rankings, four, as the national champion was Stanford: the Dickinson System, 1926; Helms Athletic Foundation, 1941; National Championship Foundation, 1980; and, the Sagarin Ratings, 1978. Navy was selected by two systems as the 1926 national champion: the Houlgate System, 1927; and, the Boand System or Azzi Ratem System, 1930. The other two schools with selections as the national champion for 1926 are: Lafayette, Parke Davis, 1933; Michigan, Sagarin, 1978.

While it quite probably simply a coincidence that after naming Stanford as the 1926 national champion that professor Dickinson then used his formula to create retroactive champions for the 1924 and 1925 systems, that the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association (AAA) seems to have done something similar in 1927 is quite striking. One could suggest, however, that it might not be quite as coincidental that several automotive journals and newspapers named champion drivers from 1909 to 1915.

While it is entirely possible that we may never know exactly what prompted members of the AAA Contest Board to create retroactive champion drivers beginning in 1927, nor why they were apparently so readily accepted, the many efforts to create retroactive collegiate football national champions might suggest that this inclination in the sports world is not unheard of. If professor Dickinson’s model of 1926 was used to determine the possible national champions of 1924 and 1925, this was also the case with several of the other systems used to select a national championship team.

A year after the Dickinson System was introduced, 1927, Deke Houlgate, created another mathematical model to determine the national championship team, which was used to determine championship teams beginning with the 1885 season. First used in 1930, the system devised by William Boand, the Boand or Azzi Ratem System, created national champions for the 1919 to 1929 seasons. In 1933, Parke Davis, a former player for Princeton and coach at Wisconsin and several other colleges, created a listing of national champions that began with the 1869 season until the 1933 season. Another former player, Richard Poling, devised yet another rating system based upon a mathematical model beginning with the 1935 season, creating championship teams back to 1924.

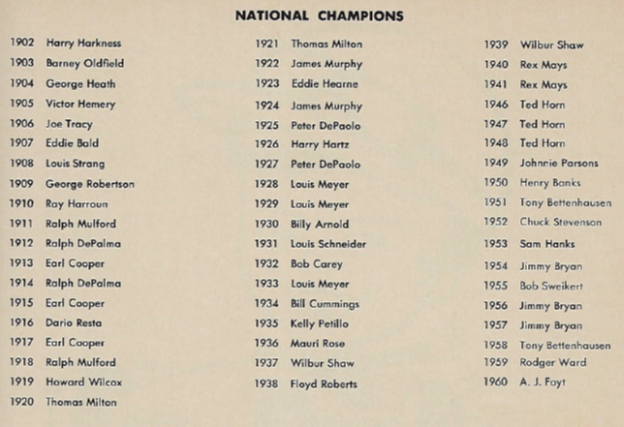

The listing of champion drivers appearing in the 1995 edition of the CART IndyCar Record Book.

I would suggest from this consideration of historical revisionism in American collegiate football that the revisionism undertaken by the AAA Contest Board and its national champions is not necessarily unique in the field of American sports history. It might also help in understanding why the retroactively-created champion drivers seems to have been accepted with few qualms, only the Chevrolet-Milton and Dingley-Robertson issues apparently drawing any attention over the decades.

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

To many people, John Bishop became a savior in 1973. For twenty uninterrupted years, starting in 1952, the Sebring 12 Hour sports car endurance race for was held under the guidance of Alec Ulmann, one of the first members of the SCCA when it was founded in 1944. In 1950, Ulmann traveled to Le Mans to take in the sights and sounds of the 24-hour race. The experience inspired him to bring sports car endurance racing to the U.S., which he did with a six-hour race at Sebring later that year – the first such event held in America.

The Sebring track itself began life as Hendricks Army Airfield, a hastily built airport used during WWII as a training site for B-17 bomber crews. After the base was decommissioned in 1945, the airport was turned over to the local community. In the ensuing years, Ulmann convinced the airport authority to let him promote a series of races using the long runways and network of access roads as the track layout. As part of the agreement, one active runway remained in operation during the race.

The start of the first 12 Hours of Sebring in 1952. The event was the brainchild of Alec Ulmann, who organized the race on the decommissioned runways of a World War II B-17 training base. Photo: Sebring International Raceway Archives

Starting with the first 12 Hours of Sebring race in 1952, the event became a crown jewel on the international racing calendar, attracting the best and brightest drivers, manufacturers and race teams from around the world. The AAA acted as the sanctioning body for the first few years, until the organization quit the racing business after the now infamous Le Mans accident in 1955 that killed more than 80 spectators. After that, Alec and Mary Ulmann formed the Automobile Racing Club of Florida (ARCF) as an entity to produce and promote the race. Alec Ulmann was the vice president of the ARCF and also acted as race secretary for the event. The SCCA sanctioned the race from 1963 through 1972, with full backing from ACCUS and the FIA.

Nothing lasts forever, however. Years of use left the track surface broken, with large chunks of concrete regularly coming loose during events. The facilities were spartan for both competitors and spectators alike. Under pressure from the FIA to improve track safety for the ever-increasing speeds of new generation racing machines and to invest in better facilities for the growing crowds, the Ulmann family announced the 1972 running of the event would be the last. After 20 uninterrupted years, the Ulmann’s were tired and wanted to move on. Sebring appeared destined to become just another dusty footnote in racing history.

Recognizing an opportunity for IMSA to take over one of the world’s most recognized sports car events, Bishop approached Bill France Sr., the founder of NASCAR and investor in IMSA, with an idea for NASCAR to put up the money to save the Sebring race. France Sr. wasn’t convinced. According to Bishop: “Big Bill never understood why anyone would pay to see an event at Sebring, whose facilities, let’s say, fell far short of those at Daytona and Talladega.” Bishop couldn’t get his friend and partner to budge.

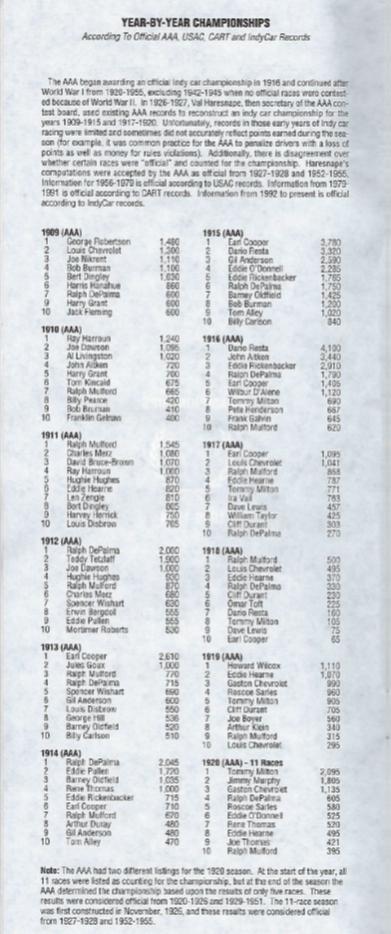

John Greenwood, on the right with Milt Minter, stepped up to bankroll the 1973 Sebring race, effectively saving the event. He would continue to be involved as a Sebring benefactor for years. IMSA Collection/International Motor Racing Research Center

Then, providence intervened. Bishop happened to be talking with John Greenwood about Sebring on the pit wall at Daytona in January of 1973 and to his surprise, Greenwood offered to put up the money to save the event, including making some needed safety improvements to the track like building a higher wall separating the pits from the main straight. With only a few short weeks to get it all organized and done, the pressure and the stakes were high. But Bishop recognized an enormous opportunity to elevate IMSA’s status in the racing world.

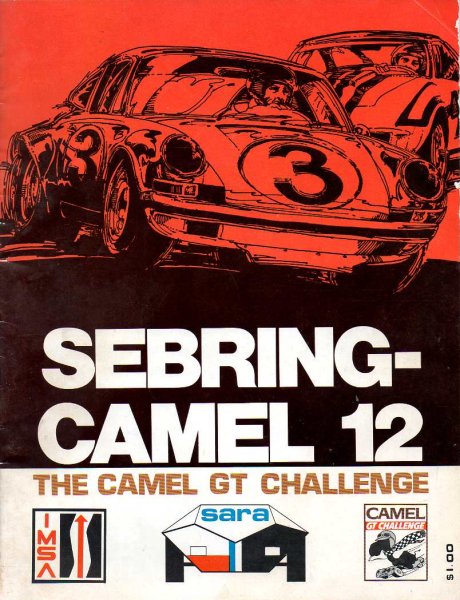

The program cover for the first IMSA-sanctioned 12 Hours of Sebring in 1973. Sebring International Raceway Archives

Reggie Smith, the ex-secretary of the ARCF, now the ex-promoter of the Sebring race, started a new organization called the Sebring Automobile Racing Association, which later on affectionately became known as the Sebring City Fathers. SARA became the official promoter of the event. Greenwood put up the prize money and made safety improvements to the track. R.J. Reynolds was more than happy to have Sebring added to the Camel GT Series calendar, which was now in its second year.

IMSA was not yet a member of ACCUS, which turned out to be a good thing, as it was not under any pressure to adhere to FIA edicts or existing ACCUS rules preventing drivers from crossing over from one member’s sanctioned race to compete in another. For unknown reasons, the SCCA board of governors voted not to interfere with IMSA taking over the race. The Club appeared to have given up on Sebring. All of this meant IMSA had a free hand to sanction an event with an almost mystical international reputation and attract drivers from any race-sanctioning body on the planet.

The runways, taxiways and access roads at Sebring have always been a challenge for racers. The Camaro shared by Luis Sereix, Tony Lilly, and Dave Voder navigates the rough pavement. Note the orange cones intended to guide the competitors at night when Sebring was pitch black and especially tricky to navigate. autosportsltd.com

The 12 Hours of Sebring became the first IMSA Camel GT event of the 1973 season. With the help of RJR’s Joe Camel advertising campaign and renewed interest in the race, a good crowd showed up, ensuring Sebring would become a fixture on the IMSA calendar for many years to come. For many people who lived through the near-extinction of the Sebring race, Bishop was recognized as one of three heroes who stepped in at the last minute to rescue this iconic event. In recognition of their contributions, Bishop, Greenwood and Smith were later inducted into the Sebring Hall of Fame.

The winning Porsche Carrera RS of Peter Gregg, Hurley Haywood, and Dave Helmick at Sebring in 1973. The traditional colors of Brumos were not used as it was Dave Helmick’s car. autosportsltd.com

The following is an excerpt from “IMSA 1969-1989” that tells the inside story of John Bishop’s life and how he created the world’s greatest sports car racing series. Available from Octane Press or wherever books are sold.

Former IMSA RS and GTU champion Don Devendorf (right) was the leader behind Electramotive Engineering, the team that fielded the all-conquering Nissan GTP ZX-T in the IMSA Camel GT Series in the last half of the 1980s. The team won the IMSA championship in 1988 and 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede

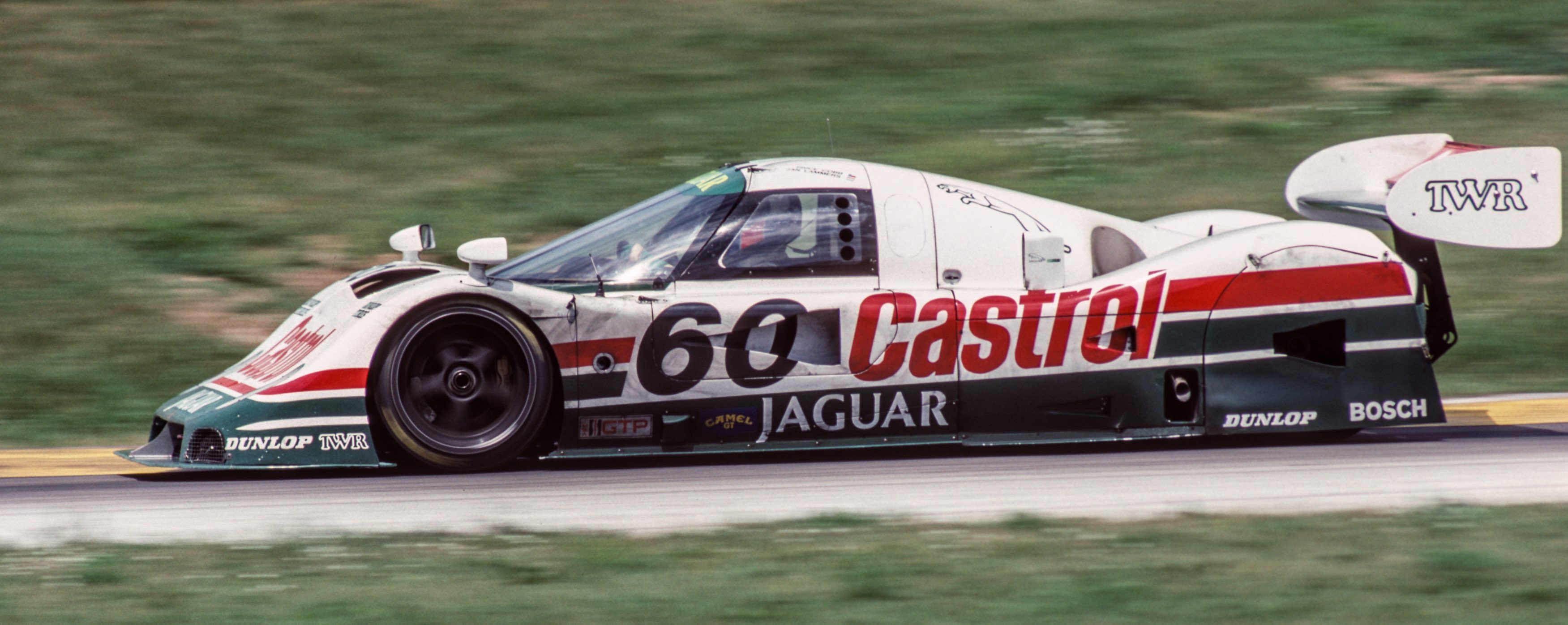

The TWR Racing Jaguar XJR-10 of Jan Lammers and Price Cobb led most of the way at Portland in 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede.

At the 1989 Portland round of the Camel GT Series, a titanic battle between the Nissans of Geoff Brabham and Chip Robinson and the two Castrol Walkinshaw Jaguars driven by Price Cobb/Jan Lammers and Davy Jones/John Nielsen lasted the entire distance. At the end of the race, an extraordinary sequence of events unfolded that created confusion and a tough decision for IMSA officials.

Jaguar ran two different cars in 1989—the XJR-9 (foreground) that featured a 7.0-liter, 12-cylinder, normally aspirated engine, and the new XJR-10 designed around a 3.0-liter, 6-cylinder twin-turbocharged motor. The cars are shown here at the previous round at Road America, sitting next to the Castrol transporter. Photo: Peter Gloede

Although the race was scheduled for 102 laps, for reasons never fully understood the local SCCA starter took it upon himself to throw the checkered flag on the 94th lap instead. About a third of the field took that flag, including the leaders – Cobb over Brabham by little more than one second. The teams knew the race was supposed to go 102 laps, so, for the most part, they told their drivers to keep right on racing. After a few cars took the checkered flag, IMSA race control realized what had happened, so they told the starter to pull in the checkered flag. The remaining cars flew by as if nothing had happened.

The Electramotive team was well known for their lightning-quick pit stops during their championship years, pictured here at Road America in 1989. Photo: Peter Gloede

Race control notified everyone on the radio that the race was proceeding to the full race distance. Five laps later, Brabham got by Cobb and took the second checkered flag after 102 laps. In the meantime, IMSA officials consulted the regulations and came to the decision that although the first checkered flag was flown early, it had to signify the end of the race: the event was over as of 94 laps and the win was awarded to Cobb/Lammers based on the standings at that time.

The now incensed Nissan team protested the results, which were held as provisional until the appeal could be heard by well-respected former driver John Gordon Bennett, IMSA’s commissioner. Bennett was the highest level of independent decision-making in IMSA’s appeal process. In other words, his decision would be final.

Realizing the intricacies of the situation, Bennett convened a panel of three other experts unaffiliated in any way with the parties in the dispute. The panel concluded that although incorrectly displayed, the sanctity of the checkered flag could not be disputed. IMSA was chastised by the panel for allowing the unfortunate flagging error to happen. The organization never again depended on local starters at races, instead bringing its own starter to every event. The Nissan team was disappointed, but the decision was accepted after one more minor protest.

At the next race in San Antonio, Nissan handed out a wonderfully designed lapel pin showing the number 83 car, a checkered flag, the words “Portland 1989” and a large screw going through the car, illustrating their feelings about what had happened in the Pacific Northwest.

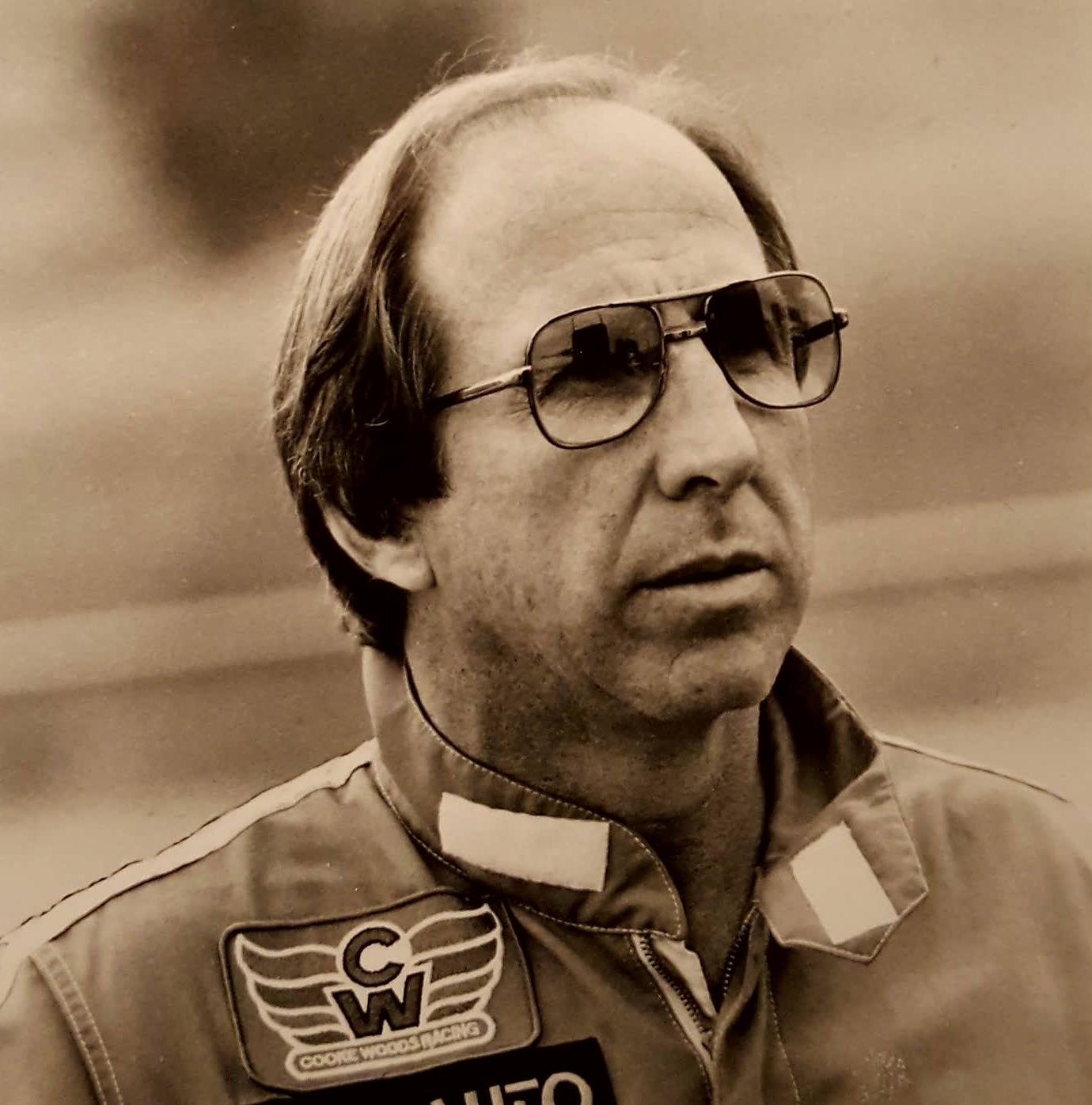

The 1981 24 Hours of Daytona shaped up to be another battle of Porsche 935s. The 935 had won the last three Daytona endurance races in a row starting in 1978. Although the 935 was based on a street 930, it was fast and reliable when properly prepared. Dick Barbour, after winning the IMSA championship with driver John Fitzpatrick in 1980, had stopped racing. That gave Bob Garretson the opportunity to continue with the same crew on his car in 1981 – a Porsche 935 (chassis 009 0030) which the team had built from a bare factory chassis in 1979. Bob had signed a new deal for 1981 to prepare the Cooke-Woods cars. This was a partnership between Roy Woods and Ralph Cooke. New Lola T600s had been ordered but would not be ready until later in the year, so the Porsche 935 would be run in the meantime. In any case, the Porsche would be more reliable for the 24 Hours of Daytona.

Team principal Bob Garretson just prior to the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981.

The car would be driven at Daytona by Bob, Brian Redman, and Bobby Rahal. We seemed to struggle a bit in getting everything ready and prepared up to our normal standards. We were still putting the car together at the track, missing a few practice sessions. We had to send Brian Redman out to qualify using the session as a brake pad bedding session, so we ended up only 16th on the grid. Brian, however, was happy with the car and told us not to worry, all was well for the race.

The race featured no less than 15 or so Porsche 935s or derivatives, as well as the factory Lancia team, running the 2.0-liter MonteCarlos in the World Championship. At the green flag most took off at high speed, pushing like it was a one-hour sprint race. It wasn’t long before engines were blowing up left and right. Many of these cars came into the pits to change engines, which was legal back then. Several went through two engines.

One of the 2.0-liter turbocharged factory Lancia Betas that ran against an onslaught of Porsche 935s in the 1981 Daytona endurance classic. This one was driven by Formula One standout Ricardo Patrese, along with Hans Heyer and Henri Pescarolo. They would finish 18th. Photo: Martin Raffauf

In contrast, we ran to our pace and soon were running at the front from the 16th starting position. At one driver change in the early evening, Brian was furious with Bobby Rahal, as he had taken the lead during his stint; Brian told Bobby he was pushing too hard! Bobby was apologetic and said, “I didn’t pass anyone, they are all falling out.” Brian wandered off muttering, “It’s too early, it’s too early.”

The Garretson Porsche 935 on the tri-oval during practice for the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981. Photo: Martin Raffauf

Around midnight, the Interscope 935 crashed with a backmarker and our car ran over some debris from the incident, which broke an exhaust pipe. This was quickly changed in the ensuing pit stop. By Sunday morning we were cruising and had a large lead of some 10-15 laps. Brian came in at about 6:45 am after a double stint, handed over to Bobby and asked, “Where’s breakfast?” Well, we said, nothing has been organized on that front yet. “Ok, he said, I’ll take care of it.” I remember thinking, how is he going to get breakfast? About 20 minutes later, Brian came back to the pits with bags of McDonald’s breakfast sandwiches. He had driven across the street to the McDonalds across from the speedway, still in his driving uniform, picked up food for the crew and had brought it back to the pits. He sat and ate with the mechanics in the pit, then went off to prepare for his next stint.

One of the friends of the team at this time, who was in our pit a lot, was Olivier Chandon, son of the French champagne house. By early Sunday, he began to get concerned, as he thought we would win, and there was crappy champagne on hand from the speedway for the Victory Lane celebration (in his view). The crew, of course, were not interested in any of this and ignored him, as we knew it was not “over until it’s over” as Yogi Berra used to say. We were just focused on making it to the end, not worrying about what kind of champagne we would drink, if any! In any case, Olivier was calling all over Daytona looking for Moet & Chandon but none was to be found. So, bless his soul, he jumped in a rental car, drove to Orlando, found the right stuff, and sped back to the circuit with the Moet & Chandon by noon or so.

The Garretson crew rushes towards the finish line to salute their car as it wins the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981. That’s the author on the far right in the blue overalls, raising his red hat in celebration. Race organizers were not pleased with this behavior and outlawed such displays in the future due to safety concerns. Photo: Peter Gloede

We ran off the remaining laps without issue and won the race. An Egg McMuffin paired with Moet & Chandon; does it get any better? It was a grand celebration and Olivier was happy he could provide “the proper champagne!” Sadly, Olivier lost his life a few years later in a Formula Atlantic crash at West Palm Beach. But we always remember and salute the Moet & Chandon!

Victory Lane celebrations were sweet in 1981 with the right champagne! Photo: Peter Gloede

The following is an excerpt from the book “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, available from Octane Press or where ever books are sold.

The race-winning ANDIAL-powered, tube-frame Porsche 935 with full “Moby Dick” Le Mans bodywork at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1983. The team of Wollek, Ballot-Lena, Foyt and Henn would go on to win the race. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

At the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1983, the Aston Martin brand was represented by two Nimrod V8 cars, one driven by A.J. Foyt and Darrell Waltrip and painted in Pepsi Challenger colors. On the pole was the ANDIAL tube frame 935, now converted to full “Moby Dick” long tail bodywork specially made for Le Mans. It was the monster of all 935s – the new body was on the same chassis that Rolf Stommelen had driven to the three straight long-distance victories in 1981. European veterans Bob Wollek and Claude Ballot-Lena were entered to co-drive with car owner and T-Bird Swap Shop entrepreneur Preston Henn.

Early on in the 1983 24 Hours of Daytona, the Swap Shop Porsche 935 leads the Pepsi-sponsored Aston Martin Nimrod GTP shared by A.J. Foyt and Darrell Waltrip. The Nimrod would drop out after 121 laps. Photo: Peter Gloede

Early retirements by JLP, Interscope, Bob Akin Racing and others kept the Swap Shop Porsche in close contact with first place through the first half of the race. After Foyt’s Nimrod also retired, Henn asked A.J. if he wanted to drive his car since it had a chance to win. Foyt agreed and got ready to climb in early Sunday morning at the beginning of what turned out to be an extended full course caution caused by heavy rain. The problem? Henn didn’t tell the other drivers.

Rain delayed the 1983 24 Hours of Daytona with a lengthy caution period and a red flag situation on Sunday morning. Photo: Bob Harmeyer

When Wollek pulled into the pits and opened the door to climb out, he saw Foyt on the pit wall dressed for battle and instantly realized what was about to transpire. Upset by Foyt taking over the car with a lead he had established and fearful the Texan would ruin the team’s race, Wollek tried to close the door and drive off. But the team physically pulled him from the car. Wollek was disgusted. He had put the car at the front and believed Henn was throwing the race away because Foyt had never driven the car before – nor driven at Daytona in the wet. But Foyt used a nearly two-hour full course caution period to learn the car and when the race was finally restarted, took off in the lead. Once again, Foyt affirmed his status as one of the all-time greats. The team went on to win the race.

Bob Wollek watches as A.J. Foyt climbs into the Swap Shop Porsche 935 early Sunday morning. Wollek’s body language tells a story in itself. Note the heavy media interest. Photo: Peter Gloede

All was forgiven in Victory Lane, but Wollek was still a bit perturbed with the whole episode. Reportedly Foyt turned to Wollek after the race and asked him; “How many times have you been to Le Mans?” Wollek answered; “At least a dozen times!” Foyt retorted: “How many times have you won?” Wollek, of course, had not won Le Mans. Foyt reminded him; “I’ve been to Le Mans once, and won.” They eventually became good friends and team mates, driving to victory together at Daytona and Sebring two years later in a Porsche 962.

The following is an excerpt from the book “IMSA 1969-1989” written by Mitch Bishop and Mark Raffauf, available from Octane Press or where ever books are sold.

The 1976 24 Hours of Daytona was possibly the most unusual Camel GT race ever run. A record 72 entries showed up and the event had a relatively normal first 15 hours. After racing through the night, the BMW CSL of Peter Gregg and Brian Redman held an enormous 17-lap lead as the sun came up Sunday morning. But when Redman stopped for fuel and tires just after 9:00 a.m., the car misfired and then stalled coming out of the pits. Stranded out on the course, Redman tried to get the car re-fired, to no avail. He eventually borrowed jumper cables and a battery from some helpful fans beside the track and somehow managed to coax the BMW back to life and limped back to the pits. In the meantime, nine of the top ten cars in the race began to suffer the same symptoms, they were coughing and coming to a halt after refueling. The culprit? Water in the gasoline.

Brian Redman’s stricken BMW CSL during the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona, after stalling out on course with water tainted gasoline. Redman is trying to get it restarted with coaching from his crew, who were not allowed to touch the car. Photo credit: ISC Archives & Research Center/Getty Image

The decision was made to red flag the race an hour after the problems first started appearing; IMSA wanted to avoid having the entire field suffer the same fate. After some investigation, it was determined that the affected teams had all been serviced by a single gasoline truck. Somehow, water had been introduced into the fuel carried by that one truck.

John Bishop conferred with Chief Steward Charlie Rainville and the decision was made to roll back timing and scoring to the last complete lap before the problem first emerged at 9:01 a.m. on Sunday morning. That call was cheered by some teams and derided by others, depending on whether their car had been felled by the bad fuel or not.

As John later recalled: “Rolling back scoring of the race seemed like the only fair thing to do. Some of the teams that had dodged the bad fuel issue were upset, but you have to remember that this was an extraordinary, unprecedented situation that was out of the control of even the most well-prepared teams or the track.”

By the time a replacement truck with fuel arrived from Jacksonville, 90 miles away, two and a half hours had elapsed. Normally, teams were not allowed to work on their cars under red flag conditions, but in this case, IMSA officials told everyone they could use the time to purge their fuel systems to get running again. Those with foam-filled fuel cells were doomed, however, because the water had been absorbed into the lining of the cell.

The BMW teams are serviced in the pit lane at Daytona in 1976 after the 24 hour race was red flagged. Teams were allowed to work on their cars to purge their fuel tanks, which had become contaminated with water. Red and green barrels were used to indicate which contained “good” and “bad” fuel. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

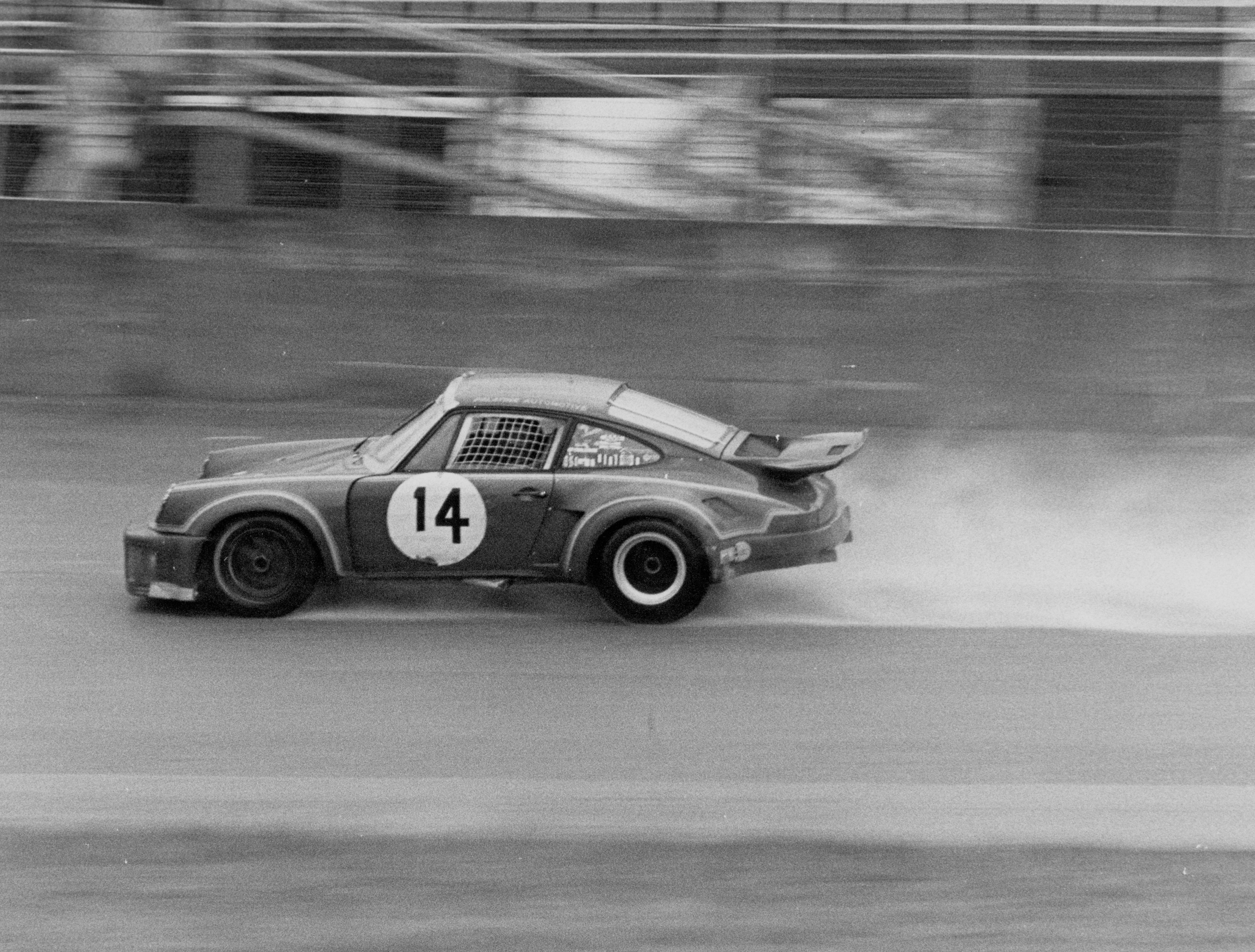

The #14 Al Holbert/Claude Ballot-Lena Porsche Carrera RSR is serviced during the lengthy red flag due to water contaminated gasoline during the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1976. The pair would go on to finish second in the race. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

Once their fuel system had been cleaned, Redman and Gregg resumed the race with their 17-lap lead intact, almost three hours after the race had been red flagged and almost four hours since the last officially scored lap. Just 29 cars restarted the race, the rest having fallen out prior to the fuel issue or having been done in by the tainted gasoline. The duo of Redman and Gregg went on to win by 14 laps over Al Holbert and Claude Ballot-Lena in a Carrera RSR. It would be the third 24 Hours of Daytona victory for Gregg.

The winning BMW CSL of Brian Redman and Peter Gregg at the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona. Photo credit: autosportsltd.com

The second place Porsche Carrera RSR of Al Holbert and Claude Ballot-Lena flies through the tri-oval in the rain at the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona. Photo credit: International Motor Racing Research Center/IMSA Collection

Back in 1974 at Watkins Glen for the United States Grand Prix, I got the chance to sit down with Mario Andretti – in the Vel’s Parnelli Jones team’s section of the Glen circuit’s Technical Centre – and hear from him about his life and career that far. Mario came across as a hyper-competitive sportsman of great – and continuing – achievement and experience and, as a man, he was friendly and engaging and one who conducted himself in a gently distinguished (and highly impressive) manner.

To me, as a hopeless race reporter – by temperament far too shy and reserved ever to ask questions of anyone to whom I had not yet been introduced – the time Mario gave me that day seemed incredible. How had I got to him? Well, both Vel’s Parnelli designer Maurice Phillippe and team manager Andrew Ferguson were fellow Brits, ex-Team Lotus in England.

I knew both well from Lotus days, and it was Andrew who overcame my natural reticence – called me over and said “Hey Mario – here’s someone you ought to meet – he’s OK”. So, there at the Glen that day, I taped a long conversation with America’s finest Italian-born racing driver. And here’s part two of the feature story based upon it that I put together over the next few days. – Doug Nye

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Continued from Part One…

The 1965 USAC big car season opened at Phoenix, Arizona, where Mario punched Dean’s lightweight roadster into the lead ahead of all the Lotus-based rear-engined cars. Then Johnny Rutherford spun in front of him and set him back to finish sixth.

Meanwhile, Clint Brawner had done a deal with John Zink, owner of the first Brabham Indy car, to copy it and build two updated Ford V8-powered replicas; one for the Dean team and one for Zink’s. The car was built, and it had scarcely turned a wheel before Andretti ran it so successfully at Indy. He went there with a second place at Trenton under his belt, and his fearless performance at the Speedway, swooping up within inches of the retaining wall out of the high-speed turns, finally made his name. It was Mario’s psychology which was right.

“Indy was, and is, a big myth in everybody’s mind. All the old-timers there look at ya and say ‘OK kid, don’t get too cocky, this is Indy’. So you think about it and you sit down and then you think ‘Shit, I’m not gonna get psyched. This is just a speedway like any other’. So you get prepared and you get it right and you do it right. Indy is special because everybody knows about it—you can’t do things there quietly—but otherwise, the Indy thing is a myth.

“What’s more difficult on the Championship circuit? I tell you, Trenton’s more difficult now. It’s 1½-miles and they’ve got a right-hand dogleg curve in the back-stretch. That dogleg’s a pig ’cos the cars can’t be set-up for it. You’ve gotta be so right through there. . .”

After his third place at Indy, which earned him $42,500, Mario won the Hoosier Grand Prix, was second in five more races and won the USAC Championship with 3,110 points. It had been his first full season, and he was the Rookie Champion. He was only 25 years old.

Mario Andretti circa 1966. Photo by Bernhard Cahier

In 1966, he won the title again, winning eight of the 15 qualifying races outright. At Indy, he qualified squarely on pole position with a new four-lap average of 165.899 mph and a one-lap record of 166.238 mph. He led for the first 16 laps until sidelined by valve trouble, to be classified a sorry 18th. Otherwise, his domination was complete.

Versatility is Andretti’s keynote. “I never retired from any form of racing’, he says, and early in 1967 he made his debut in NASCAR racing, taking on a Holman and Moody Ford Fairlane in the magic Daytona 500. He qualified for the race at a better than average 177 mph, but it was nothing startling. Then late in practice his red and grey Fairlane stormed around at 182 mph and some of the skeptical NASCAR faithful took a second look at the little man from Pennsylvania.

After a fierce late-race duel with Fred Lorenzen, it was Andretti who stormed to win the 500 —the first USAC and first non-NASCAR driver to do so. ‘Tis said that Kate Firestone was astonished by the man. “Look at him, he’s so teensy!”, she said. The Detroit News commented sagely, “…He’s toughsy and fastsy too…”.

Mario is one of the very few drivers ever to win the Indianapolis 500 (1969) and the Daytona 500 (1967) in their careers. He’s pictured here in the winning machine at Daytona.

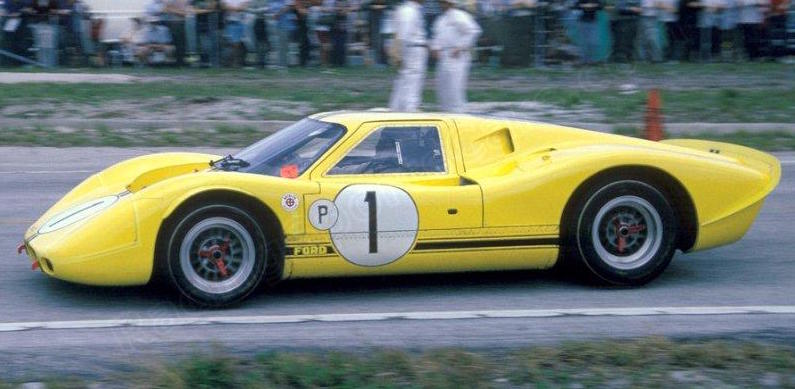

Road racing was the next field to conquer. Mario had run a NART Ferrari in the Sebring 12-Hours the previous year, but a tragedy-darkened run ended in retirement. For ’67 he was paired with Bruce McLaren in the prototype 7-litre Ford Mark IV, and they won. Next day he was in Atlanta, running another 500-mile stock car race until repeated tyre blow-outs snuffed-out his drive against the wall. At Le Mans, he was paired with Lucien Bianchi, and their big Ford was running in second place in the small hours when the Belgian brought it in for refueling and a routine brake pad change.

The team of Bruce McLaren and Mario Andretti won the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1967 driving this prototype of the Ford GT 40 MkIV. Photo: George Boron.

It was then that Mario had one of his biggest frights; “The pads went in backward and cracked the disc. As I braked down into the Esses, right out of the pits, they just jerked the wheel out of my hands and the bitch car hit just about everything. I got to the side of the road when Roger McCluskey appeared, thought I was still in the wreck and smashed up trying to avoid it. Then Jo Schlesser came over the top and smashed his Ford as well oh, what a bitch that was…”.

Indy that year had Andretti on pole for the second time, but he was out of the race when the right front wheel parted company. He won seven Championship rounds and was leading the Rex Mays race at Riverside with only three laps to go when a stop for fuel cost him victory, and what would have been his hat-trick of National titles. Instead, A. J. Foyt topped the ratings.

In December Al Dean died, and Andretti took over the racing stable himself, still with Clint Brawner and Jim McGee preparing the Championship cars. Indy was a disaster as he started from row two and became the first retirement after only two laps, with engine trouble. He fought back in the rest of the series, winning three times and placed second 11 times. But the Riverside race cost him the title again, this time to Bobby Unser, by only 11 points. On road circuits, he had driven for Alfa Romeo at Daytona, and then Colin Chapman offered him a Gold Leaf Team Lotus drive in the Italian and US GPs. He was ruled out of the Italian race because he had a USAC event to do within 24 hours, but at Watkins Glen, he shook everybody by taking pole position in his first Formula 1 race. It all fell apart when the car’s nosecone fell to bits and its clutch failed.

Mario Andretti poses with the STP-sponsored team owned by Andy Granatelli (far right) that won the 1969 Indianapolis 500.

Then came 1969, backing from Andy Granatelli and STP and a first win in the Indy 500. During practice, Mario crashed very heavily in the Lotus 64, and he raced his ancient Hawk-Ford. “It was just a spare car you know, not even cleaned-off since Hanford. It had just two days of practice and was never out of third. I had to back-off in the race, it showed 260-degrees oil temperature, but we won. It was the first time … it was very satisfying”.

He went on to win eight more races and his third Championship. A works Ferrari ride into second place at Sebring meant a lot to him and with a brutish McLaren-Ford he struggled manfully to two good CanAm sports car placings. Meanwhile, he had great faith in four-wheel drive, and Colin Chapman pinned his Formula 1 hopes on the American’s faith. Unfortunately, “… it was worth a try, but it proved absolutely not worthy of road racing. Tyre development solved the traction problem, and anyway, the car’s straightaway speed was down. In a high-speed corner, the things were just fantastic, which is why they worked at Indy, but otherwise, no way…”.

At the Nurburgring, Mario had a short German GP. “I’d never practised with full tanks, an’ then I got a good start and was up with them. But the thing was bottoming on the bumps and then up over that Flugplatz, it bottomed so bad, I caught a wheel on the catch fence and took it off. I didn’t crash, I just slid to a stop but then Vic Elford came over in that McLaren and hit the wheel. He rolled upside down over a drop and I went down and held the car up off his arm on my shoulder and reached in and knocked the switches off. Poor guy, I felt kind of responsible, but what can you do, you know?”

In 1970 Mario was back in a Ferrari, this time a 512 in which he helped Vaccarella and Giunti to win at Sebring. The Granatellis backed him in the ill-conceived McNamara Championship car and in a similarly unsuccessful Formula 1 March. He was fifth in the USAC National Championship, which for him was a big fall. Then came the Formula 1 signing with Ferrari for 1971. “I enjoyed that to no end. It was something I had dreamed of since I was a kid at Lucca and when I won in South Africa it was the most satisfying thing I’d ever achieved.

“Psychologically it was a very great thing, and the win at Ontario was good too because those cars were the real t’oroughbreds. It’s who you beat that matters—I’ll take wins any way they come—but to be in front of Stewart both times was great…”

That season was his last with the Granatellis (“I’m still personally good friends with Andy, but I couldn’t agree with the way things were done there, those brothers, you know?”).

He was put out of Indy in an early four-car crash, and second at Trenton was his best finish of the year. He was ninth in the point standings and left the STP fold to join Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones for 1972.

“That Vel…”, he says, indicating the big-built greying Californian motor dealer smiling happily beside his Formula 1 car, “… he’s such an ent’usiast you can’t believe it. I wanna race and be competitive and that’s why I joined Vel’s — they’re 200 percent…”

The Maurice Phillippe-designed Viceroy Special which Mario drove was not as competitive as had been hoped. “But the biggest problem with the car was its big build-up. First time we ran we had news people crawling all over it, and when it wasn’t quite right we got all the crap, you know. I could’ve killed that PR man!”

Most of Mario’s winning that season was with the Ferrari sports car team, partnering Jacky lckx, for they took the Daytona, Sebring and Brands Hatch Championship rounds. “I enjoyed that long-distance racing, it disciplines you to go quick without destroying the car”, while in USAC “I led nearly every race only to blow engines. We had a piston problem…” That was expensive, as at Indy where Mario’s detuned car was fifth at 190 laps only to run out of fuel and be placed eighth. Team-mate Joe Leonard ran his identical Samsonite Special more slowly and gained in reliability to win the Championship.

The winning Ferrari 312PB (#0888) of Mario Andretti and Jackie Ickx at Daytona in 1972. The race was shortened to 6 hours that year. The pair would repeat at Sebring two months later. (Photo: Levetto)

The ’73 season saw Vel’s Parnelli using re-designed Phillippe cars in which Andretti won early on at Trenton, and set a world’s closed-circuit outright lap record at Texas World Speedway. Thereafter fortunes again took a dive, in European eyes it seemed as though Andretti was running out of steam, we didn’t hear much of him any more…

Then in April this year, he shared the winning Alfa Romeo in the Monza 1,000 Kms, at the seat of Italian motor racing. That must have meant a lot? “Yeah, that was OK, but it was sports cars, and who did we beat? The Grand Prix …” a faraway look at the Parnelli car “…would be different”.

The ’74 Parnelli USAC car put in just one race, at Trenton, where Mario put it on pole and led until the engine failed. Vel’s Parnelli wheeled a Formula A/5000 Lola into their Torrance, California, workshops, and Mario took it out on to the American Championship road circuits, winning at Elkhart Lake, Watkins Glen and Riverside. “ On a road circuit Mario is as sharp as ever”, they said, and when it came to the team’s Grand Prix debut with their brand-new “… four-inch lower Lotus 72” he proved it.

“Formula 5000 has become good racing,” he says reflectively, “… and lucrative too, with purses of $55,000-60,000 for the races, and $16,000-18,000 for a win. But that Brian Redman, you know, he has been really tough competition, fantastically quick. Jim Hall’s operation too, they’re tough. But it’s good practice for Formula 1, and this is where I wanna be. I figure I’m not getting’ any younger, and I’m trying to do it seriously now. Next year I’m gonna do Formula 1, 5000 and the three 500-mile track races, I guess that’s enough…”

Andretti is married, has two sons and a small daughter, and still lives in Nazareth where they have named a street (Victory Lane) in his honour. His last Fl race previous to the Vel’s Parnelli venture was the Glen in ’72 when his Ferrari was placed sixth and at least some of the fans recalled that. While we were talking a teenaged kid came bursting in, eyes aflame with enthusiasm (if not much knowledge). “ Hey, Mario, I’m looking for ya, man. You racin’ this afternoon? What ya drivin’? Ya drivin’ Lotus? Ya drivin’ Ferrari?” etc, etc. Andretti’s natural reaction was “ thanks, but excuse us, we’re talking here”, slowly changing to muted irritation as the kid’s ignorance showed. He eventually backed off moaning “Hey Mario, man, I was lookin’ for ya, man…lookin’ for ya…” to be swallowed up in the crowd.

Mario Andretti turned his powerful shoulders, brown eyes darkened; “That kinda thing bugs the bell outa me”, he snorted, “…but I guess he’s got ent’usiasm”, and his tanned face creased into a grin. Maybe he was thinking where his “ent’usiasm” has put him, and next season he’s going to be running hard to improve on that.