By Larry Ott

Courtesy of Area Auto Racing News

The name of Watkins Glen International holds a very dear and revered place in the motorsports world, as does the Argetsinger family name. The late Cameron Argetsinger first brought road racing to the streets of that Finger Lakes community in 1948.

Cameron Argetsinger was a founding father who turned his dream of bringing racing to Watkins Glen into reality. Since then, numerous racing series have raced on the various track configurations that have existed at The Glen.

Weaved throughout Watkins Glen’s long racing history have been numerous visits from NASCAR, which staged its first race at The Glen in 1957, with subsequent visits in 1964 and 1965.

Since 1986, NASCAR has returned to The Glen each year and will return again this August for the annual NASCAR Cup Series event.

J.C. Argetsinger is the oldest son of Cameron Argetsinger and experienced first-hand, starting as a young boy, the interactions between his father and NASCAR founder, the late Bill France Sr., as plans to bring NASCAR to Watkins Glen were unfolding those many years ago. J.C. publically shared many personal remembrances of both his father and France at a recent conversation series event held at the International Motor Racing Research Center in Watkins Glen. J.C., a retired Schuyler County (NY), judge and attorney, served as president of the IMRRC from 2007 until retiring from that post in 2015.

Of great interest is the historical fact that the first race at Watkins Glen as well as the birth of NASCAR both occurred in 1948. NASCAR was launched in February of that year while the first street race in Watkins Glen was held in October. Thus the seeds of the Argetsinger-France family connection began that year.

“My father was a 27-year-old guy and how he ever persuaded the village to hold the race through the main street of Watkins Glen in 1948 was amazing,” Argetsinger said. “It was my father’s forceful personality and the Chamber of Commerce of Watkins Glen and Don Brubaker who was at the Seneca Lodge and who was president of the chamber, that made it all happen. Don wasn’t at all interested in racing but he just realized that it probably would be a good way to extend the tourist season.”

Thus racing commenced in Watkins Glen.

During the running of the first race at Watkins Glen in 1948, J.C saw a tall man and his car arrive in the village. He had never seen the man or car before. This aroused curiosity within a very young J.C. It wasn’t until years later that J.C. and his father would connect the dots and discover that the man J.C. saw observing the 1948 race was Bill France himself.

“I was six years old and I was selling programs and I’ve told the story and it really wasn’t documented anywhere else that Bill France Sr. was there at the first race at Watkins Glen in 1948,” Argetsinger said.” A number of years later I described it to my father. I saw this very extraordinarily tall man in a brand new Hudson which was an unusual car in 1948. It was a two-door coupe. I remember it so well. There was a sign in the back of the car that said ‘NASCAR.’ I said to my father that very day, ‘what is a NASCAR?’ He said: ‘Oh, that’s some other organization like the SCCA.’ So at the running of the first race my father never even knew that Bill France was there and nobody else did either. Again, it was a number of years later I was telling my father the whole story and we both suddenly realized that the man I was describing was Bill France. I’v got my theories, but there was Big Bill France seeing what his northern cousins were up to with their sporty car racing, checking things out. So my father was never aware that Bill was at the 1948 race. Of course, Bill France was just starting out then and my father was just starting out so they both were kind of relatively unknown at the time.”

Argetsinger has very fond memories of his father’s first encounters with France. It would eventually bond The Glen and NASCAR together. “What an amazing, charismatic, and larger-than-life personality that Bill France had,” Argetsinger said. “I met him and my father did also. A number of times he came to our house. John Bishop, who worked with France for many years when they formed IMSA, told many stories about how Bill could stand next to somebody and put his arm around him and say, ‘Let’s reason together.’ Bill was quite persuasive. Bill was able to put NASCAR together, but he had bigger things in mind.”

Some of those bigger history-making things would eventually clear the path for NASCAR to come to The Glen for the very first time in 1957. “Bill sponsored a few races in the north, and then in 1957 NASCAR raced at Watkins Glen,” Argetsinger said. “It was a major race. He and my father really hit it off and they got acquainted, obviously, also at the 1964 and 1965 races.

“Also, early on Bill France had an eye on international racing. At the time my father was just beginning to promote the U.S. Grand Prix and Formula Libre in 1958 and international sports car racing. My father was at Sebring in 1957. Alec Ullman at the time was the big international promoter with the Twelve Hours of Sebring and he had a lock on things. My father looked out and this plane landed in the field at Sebring and Bill France got out with four of his lieutenants. Alec was very jealous about the credentials. You didn’t get on the course without clearing through Alec first. Big Bill and his lieutenants strolled across the field and I said to my father, ‘Didn’t someone try to stop him?’ My father said that would have been like trying to stop a wave in the ocean. Bill just swept in, talked to all the international drivers and team people. He did his business and left after 45 minutes.”

J.C. recalled a time in 1964 or 1965 when France made a visit to the Argetsinger household and his younger brother, the late Michael Argetsinger, had an interesting experience with NASCAR’s head man. “My younger brother Michael had been driving his old stock car at some of the oval tracks and local dirt tracks,” Argetsinger said. “Michael was a great racing enthusiast. He and Bill France hit it off at our house. Bill said to Michael that he was going to get Michael a NASCAR international driving license. Michael had been racing in just a few local races at age 20 or 21 on the local oval tracks. It turned out to be such a great gift because the next year Michael moved to Europe and he was able to move immediately into Formula Ford and international sports car racing by virtue of the fact that Bill France had given him a NASCAR license just based on a conversation at our home. Michael raced for ten years in Europe.”

Cameron Argetsinger would get even more involved with France as the years rolled by. It included the U.S. Grand Prix that ran at Watkins Glen from 1961-1980. “France worked very closely with my father because France was on the ACCUS (Automobile Competition Committee for the United States) which was our representative to the FIA,” Argetsinger said. “France had a tremendous personality and he always favored Watkins Glen. There were other tracks that were competing to get the sanction for the U.S. Grand Prix. France was always in my father’s corner and helped get us the U.S. Grand Prix.”

France was also involved in the process that helped take Watkins Glen International from financial woes suffered in the early 1980s back into business as a racing facility for the years ahead. “In the early 1980s when Corning Inc. bought Watkins Glen, my father, Bill France, and NASCAR participated in organizing the races at Watkins Glen before they became full partners,” Argetsinger recalled. “My father had a reception at our home. He introduced Bill France to those in our community. Big Bill by this time was kind of a senior ambassador and was just absolutely charming with his personality. My father thought it was so good for Watkins Glen that after all these years he was still involved with us. I was Bill’s personal bartender that evening and I remember he very much enjoyed the bourbon that I served him.”

While Watkins Glen has mostly been steeped in rich road and sports car racing traditions over its long history, there is no question that the annual NASCAR weekend at The Glen has long ago established itself as easily the biggest and most successful event on the yearly racing calendar there. J.C. says that his father was very proud of this development. “A reporter asked my father one day, whose career was sports cars and Formula One cars, if it disturbed him that Watkins Glen now is mostly synonymous with NASCAR and my father said ‘Nonsense,’” Argetsinger stressed. “My father stated that NASCAR breathed new life into the course and provided not only great revenues for the community with the huge spectator base but made it possible to finance the various sports car and amateur events that are held at the track throughout the year.”

Cameron Argetsinger died in 2008 while Bill France Sr. died in 1992. Separately, both men enjoyed much success, but when paired together for so many years, they formed an unbeatable combination. Both men fed off of each other’s efforts to benefit motorsports.

The motorsports world has been truly blessed that both men were involved in the sport and their contributions will live on. J.C. feels most fortunate to have grown up in a life that involved both men. “It allowed me to experience the sport at a much different level and in so many ways, and it was a very interesting part of my family life,” Argetsinger said. “I’ve been truly fortunate, as has been my family.”

By Terry O’Neil

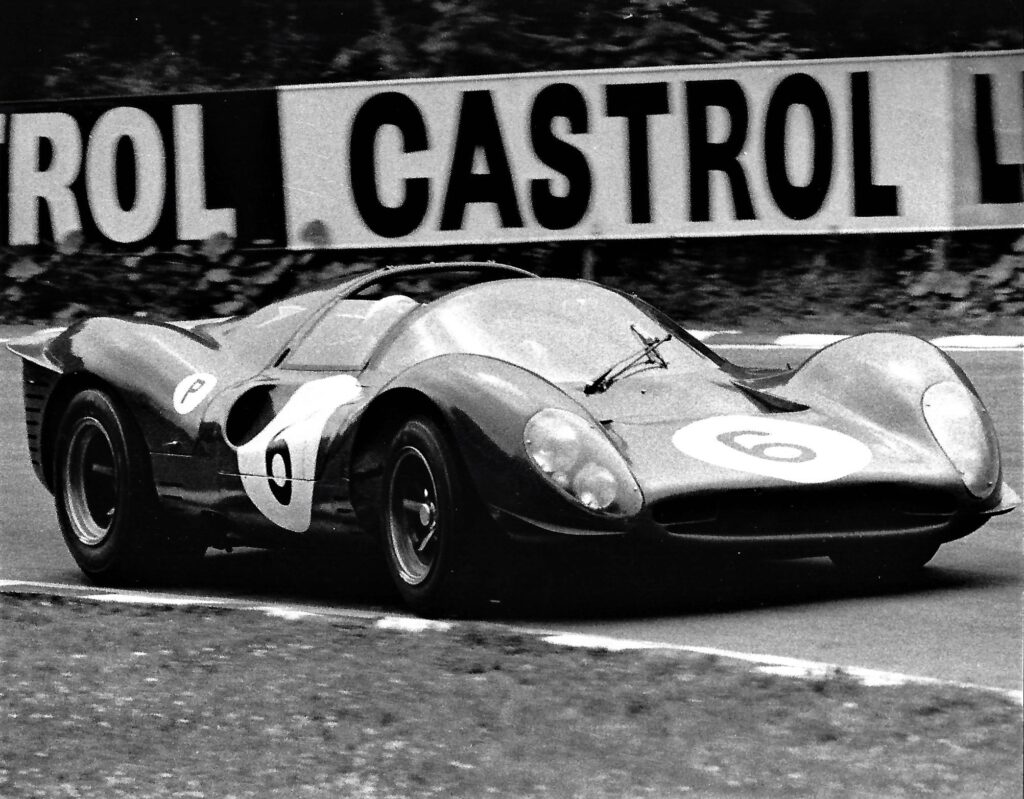

Brands Hatch Circuit, situated in the rural county of Kent, was the venue for the eighth round of the Manufacturers’ Championship for prototype cars on July 30, 1967. It was the first time that Brands Hatch had been used for the series and the drivers found that it was quite different from the other continental venues that had their long sweeping curves and lengthy straights. By contrast, Brands Hatch was shorter in length, 2.7 miles, with hills and tight corners to contend with which proved a challenge to the engineers who were responsible for setting up the cars.

Whilst Ferrari just missed out on victory in England at Brands Hatch on that day, the results were significantly good enough to help Ferrari achieve its ultimate goal for 1967 in winning the Manufacturers’ Championship for prototype cars, thus taking revenge on Ford who had just pipped Ferrari to the Championship in 1966, and Porsche who had been leading the Championship up to this point in 1967.

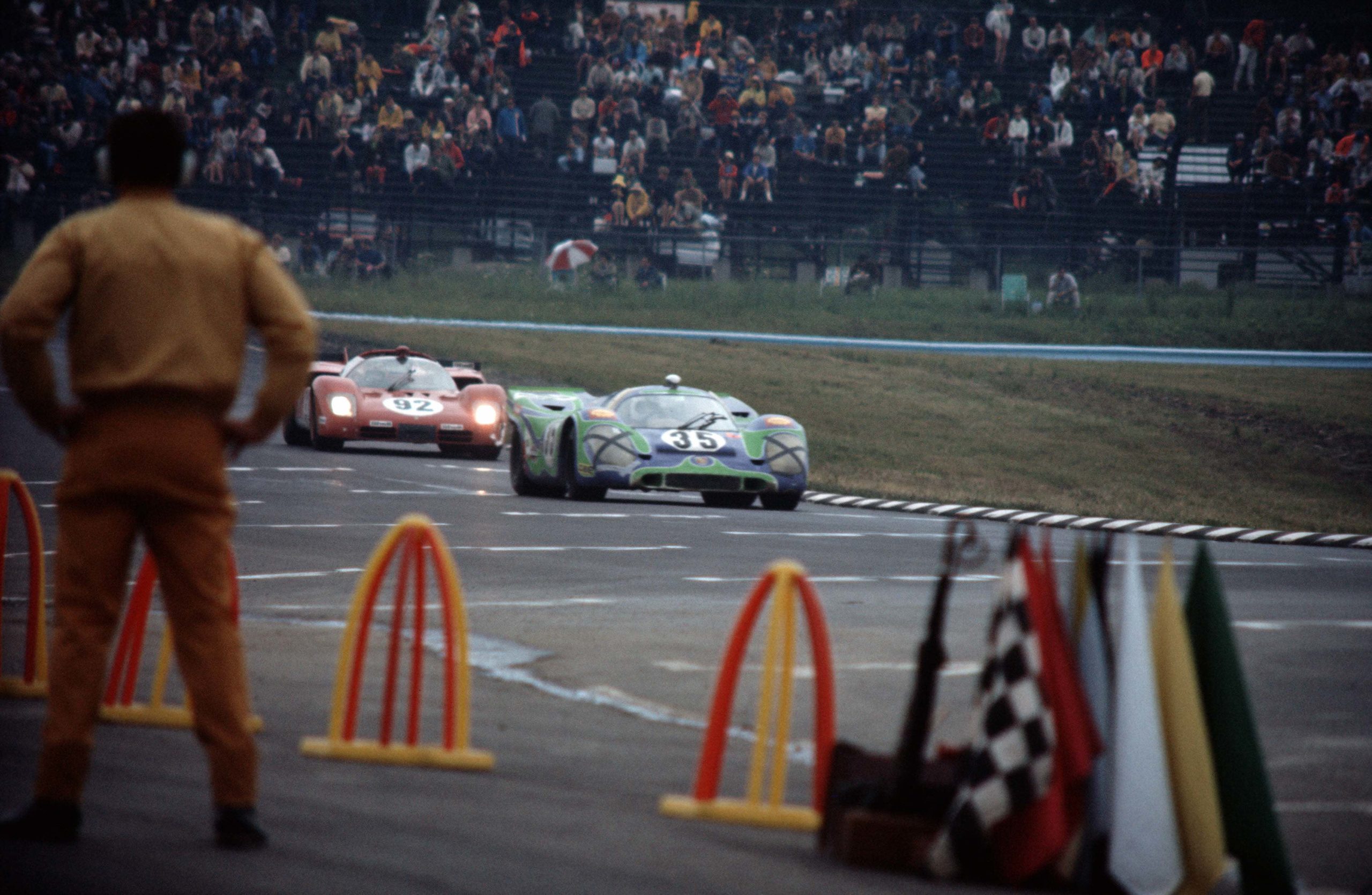

Sefac Ferrari sent three identical open-top 330 P4s for Amon / Stewart, Scarfiotti / Sutcliffe, and Hawkins / Williams, while a 412P was entered by Maranello Concessionaires for Attwood / Piper. Lined up against them and determined to secure the Championship were five Porsche Works entries consisting of four 910 models for Hill / Rindt, Siffert / McLaren, Elford / Bianchi, Schutz / Koch and a 907 model, the latter for Herrmann / Neerpasch to drive.

The Scarfiotti / Sutcliffe Ferrari P4 making one of its two planned pit stops for fuel and driver changeover.

Five American V-8 engined cars were also competing in the prototype category. A Chaparral 2F was prepared for Spence / Phil Hill, three Lola T-70 cars for Hulme / Brabham, Westbury / DeUdy, and Surtees / Hobbs and a Mirage for Thompson / Pedro Rodriguez. Altogether there were twenty-one prototype cars entered into the race which also included fourteen cars entered in the Sportscar Championship class. It was in this category that Ford came to the fore, where four GT40s were up against three Ferrari 250LMs in the over two-liter class and three Porsche 906s in the under two-liter class.

Qualifying ended with two Lolas and the Chaparral on the front row of the grid, two Ferrari P4s on the second row, and the third row having two Porsche 910s and the other Ferrari P4 in place. Surtees’ Lola led off from the front row followed by Hawkins and Scarfiotti in P4s from the second row and Spence in the Chaparral.

The Ferrari P4 driven by / Williams led the race briefly but finished in sixth place having covered 204 laps.

Hawkins took the lead on the second lap, with Hulme inching ahead of Phil Hill for fifth place. Hawkins’ lead would prove to be short-lived as first Hulme and then Spence and Scarfiotti went past him, relegating the Ferrari 330 P4 to fourth place.

Over the next few laps, Hulme began opening up a gap and set the fastest lap of the race in the process. Behind him, Spence and Scarfiotti were holding down their positions waiting for Hulme to falter. They didn’t have too long to wait as on the hour Hulme’s Lola coasted into the pits and out of the race with a broken rocker arm. Spence, having inherited the lead, made the most of his opportunity with a clear track ahead of him, using the powerful Chevrolet engine to open up a gap before coming into the pits for a driver change-over with Phil Hill, and losing the lead as Rodriguez with the Mirage had climbed up the field and had the momentum to take over the lead, with Siffert’s Porsche behind him. It was to be a short-lived situation because neither of the cars had pitted yet, so when they did Hill in the Chaparral regained the lead.

After the round of pit stops the action on track became frantic, as Phil Hill had to make his way to the pits with a flat tire, and Dick Thompson undid Rodriguez’s hard work by spinning the Mirage into an earthen bank on lap 87, and out of the race.

A Ferrari P4, #6, was driven by Chris Amon and Jackie Stewart to second overall, covering 211 laps, sealing the Manufacturers’ Championship for prototypes for Sefac Ferrari.

At half distance, the Amon / Stewart Ferrari P4 led the way from the Siffert / McLaren Porsche 910, Phil Hill’s Chaparral, and the Hawkins / Williams Ferrari P4. Generally, the attrition rate was low, with only seven of the thirty-five starters pulling out of the race. With the Porsche driven by Graham Hill being one of those cars, the Porsche team made a tactical change to their driver pairings and replaced Koch with Rindt in the Schutz car as the Austrian was quicker than Koch.

The Ferrari 412P entered by Maranello Concessionaires and driven by Piper and Attwood to a seventh place finish, covering 202 laps.

Having spent a considerable amount of time in the pits because of fuel problems in the first half of the race the Surtees / Hobbs Lola made it up to seventh place before the engine seized, ending its race, giving Hawkins breathing space, as he had troubles of his own when the rear bodywork of his Ferrari came adrift and he had to pit to have it wired back together again.

The next series of driver changes put Spence back in the Chaparral in front of Siffert’s Porsche 910 and Amon’s Ferrari P4 with Spence widening the gap at the front as each lap went by. Attention was drawn to the battle for second place which would effectively decide the outcome of the prototype championship. Less than two hours of the race remained when Siffert pitted for the final time, and after an efficient stop came out in third place behind Amon, but knew that Amon would also have to stop soon. Amon was motoring in top form and building a cushion over the Porsche which was now heavy with fuel again. At the last possible moment, Amon pitted, stayed with the car, and was out on track again within forty seconds and having a cushion of a minute to the Porsche. It was enough to secure the second spot as Siffert’s Porsche could do nothing to put up a challenge. The Porsche team had to accept defeat in the prototype championship by a five-point margin.

Meanwhile, the Chaparral motored on without any unforeseen trouble to take the overall victory with only Amon’s Ferrari on the same lap as the Chaparral as the flag fell.

The first car in the Sports Car category to finish was the Porsche 906 driven by Tony Dean and Ben Pon in eighth place overall, ahead of the Ferrari 250LM driven by Hugh Dibley and Roy Pierpoint.

Part 1: From Small Beginnings

Following World War II, the United States economy was beginning to grow slowly during the time of peace, benefiting the everyday requirements of its population. Along with its growth, a demand for increased leisure activities prevailed.

Motorsport had been one of the last leisure activities to recover for several reasons. Some pre-war established race drivers had either been injured or did not return from the war and as a result race track owners had a hard time re-establishing the level of competition to satisfy their customer base. Add to that the fact that domestic production of cars had only just geared up again, with the consequence that cars for use other than being a family necessity were not easy to come by.

However, the mid-1950s were witness to a change in fortunes for a few people who were lured by the growing number of sports cars coming into America from Europe. It was from this group of people that a small number of owners in and around the New York area took it upon themselves to form a club. Firstly, because they enjoyed their cars, and secondly because it was their aim to enter them into races, and hopefully win monetary prizes – something that was not possible by being a member of the Sports Car Club of America.

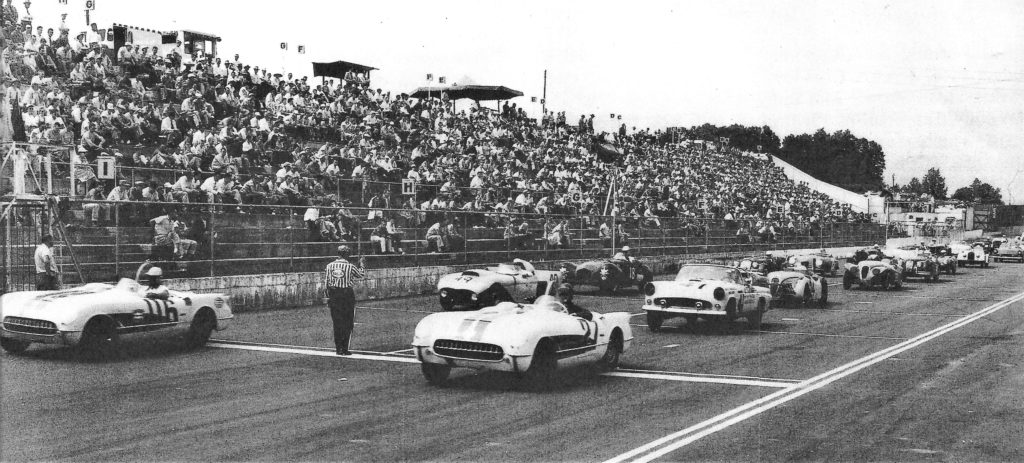

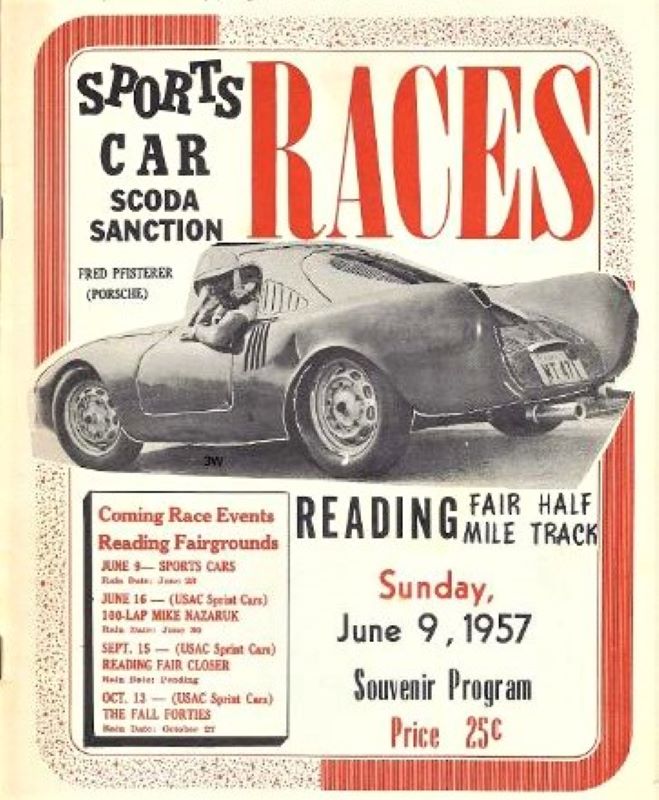

It was decided that the club would be known as the Sports Car Owners and Drivers Association (henceforth called SCODA in this article), and it was officially incorporated in New Jersey on October 1, 1954. The Club was based on Long Island with Bill Claren appointed as its first president. Claren, with Stan Becker, Joe Ferguson, and Ray Erickson, took the decision to administer the Club from Long Island despite the presence of the established Long Island Sports Car Club in that location. One of the Club’s first actions was to affiliate itself with NASCAR and approach any dirt track or oval that would consider including a sports car race into their program of Midget or Stock car races. This was not quite as audacious as might first appear as the track race organizers knew some of the SCODA members and were already holding NASCAR-sanctioned race meetings.

The strategy appeared to work well as SCODA’s traveling road show offered short track promoters variety for their weekly programs, something that was a welcome added attraction for the spectators. So much so that the track organizers were prepared to put up some prize money for the drivers. The money that changed hands was modest, the total purse averaged about $1,000, and of that, the winner’s share was around $200. With the swift introduction of appearance money in 1954, everyone headed home with something in their pocket.

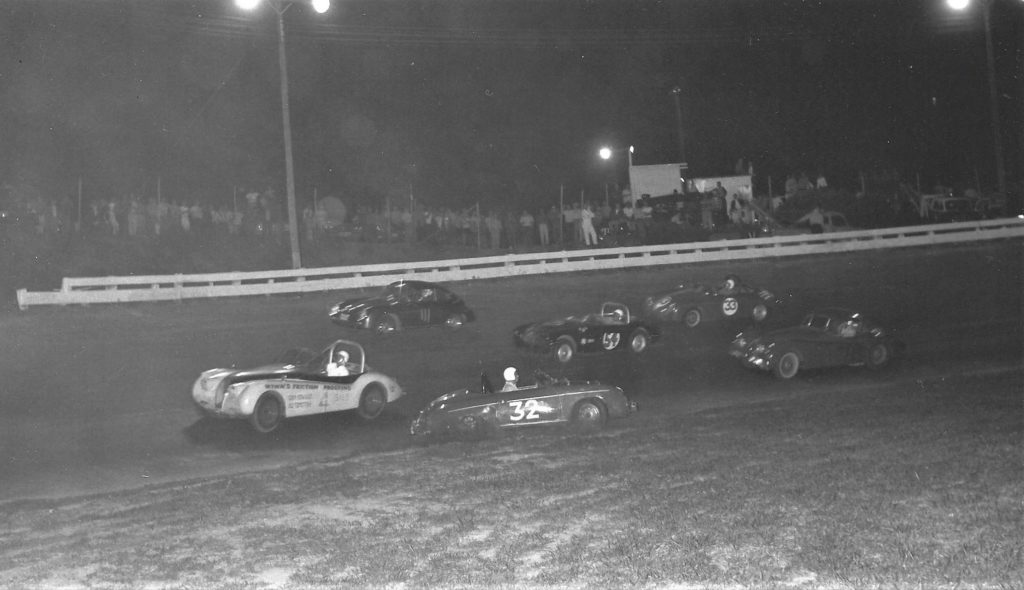

Through their affiliation with NASCAR, SCODA was able to utilize some of the many speedway ovals which existed in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states of America during the 1950s, often forming part of the larger racing program. Not only did they race for money, but they also formed their own race championship series, possibly the first club in America to do so outside of the SCCA. Their format for the championship was quite simple, the cars being divided into either the under-1500cc or over-1500cc category with points awarded for finishing positions in the feature race at each venue. It remained that way for several years before a change was made. (It should be noted that SCODA had always taken a rather wide view on the exact definition of a sports car, with a number of creative interpretations turning out at some of the meetings. As long as the cars met the technical and FIA specifications the cars were allowed to compete. A typical race meeting format would be to have heats, semi-final, consolation, and a feature race in the same manner as the Midget and Stock Car events.

Through their affiliation with NASCAR, SCODA was able to utilize some of the many speedway ovals which existed in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states of America during the 1950s, often forming part of the larger racing program. Not only did they race for money, but they also formed their own race championship series, possibly the first club in America to do so outside of the SCCA. Their format for the championship was quite simple, the cars being divided into either the under-1500cc or over-1500cc category with points awarded for finishing positions in the feature race at each venue. It remained that way for several years before a change was made. (It should be noted that SCODA had always taken a rather wide view on the exact definition of a sports car, with a number of creative interpretations turning out at some of the meetings. As long as the cars met the technical and FIA specifications the cars were allowed to compete. A typical race meeting format would be to have heats, semi-final, consolation, and a feature race in the same manner as the Midget and Stock Car events.

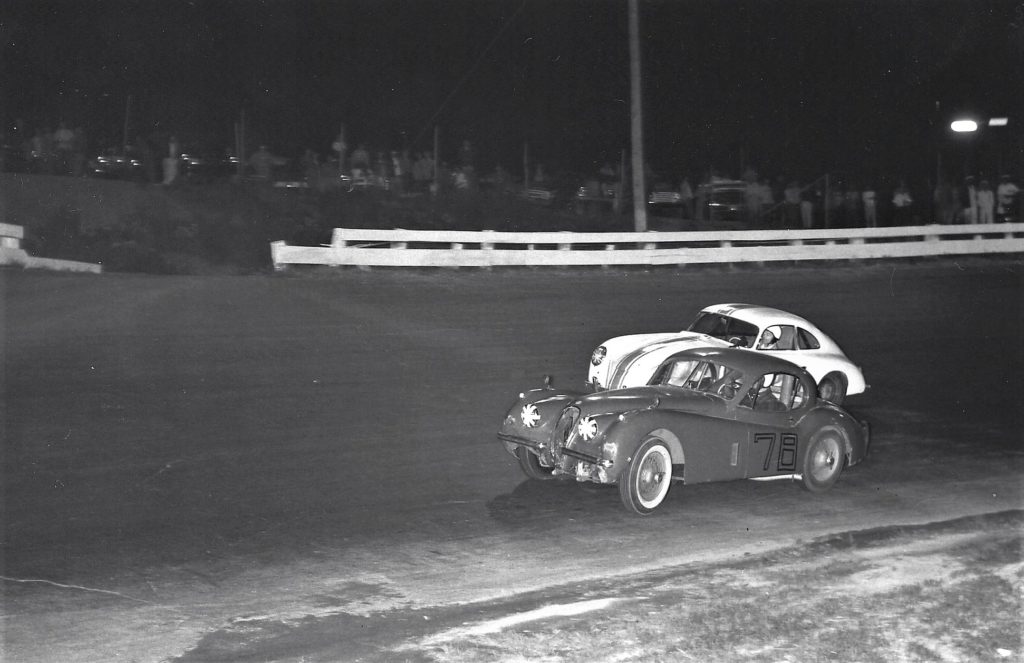

In 1954, nine championship races took place at various oval tracks located in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, with a total purse of $9,500 on offer. The first race took place on a one-quarter-mile paved oval at Plainville Stadium on July 3, where Bill Claren took the feature race in his Jaguar XK120. He followed his victory up the next evening when he appeared at Wall Stadium in Belmar.

Morristown Speedway was the next venue, and this time it was Ed Schaefer who took the honors and the lion’s share of the purse, driving Paul Whiteman’s Jaguar XK120. Despite some stern opposition from the likes of Stan Becker’s Ford and Bill Boyd’s Miller Special (a 1927 model brought up to sports car specification with added fenders and a Corvette engine), the Jaguars looked unbeatable in these early races. A large field of entrants appeared at Hatfield Speedway, all keen to try out the recently laid “rubberised asphalt” that had been spread over the one-half-mile oval. However, the result was the same as the Jaguar XK120 driven by Pete Bell headed five other Jaguars to the flag. In the under-1500cc section, a selection of MGs performed well, though had no chance of obtaining good overall positions.

Jim Reed won at Roosevelt Stadium in September on the one-quarter-mile track in his Jaguar XK120, but the results from other races for 1954 have eluded me, though it would appear Bill Claren must have been among the front runners as he was awarded the 1954 SCODA driver’s championship.

Buoyed by the success of the 1954 season, SCODA’s progression appeared to be inevitable. In 1955, it was reported in National Speed Sport News that SCODA would be willing to sign up for races within a 200-mile radius of New York City and had up to fifty cars and drivers ready to race. It also sent a signal to the SCCA: “Despite the accepted standard that sports car enthusiasts do not race for money, a little group of aficionados from the New York area are kicking over the traces and if their early success is a portent of things to come, the old traditions may be in danger.”

The program of events expanded for 1955 with 11 meetings taking place, the Civic Stadium in Buffalo being the furthest venue from New York City, and had an expanded purse of $14,250. With the increase in membership came some more competitive cars. Fred Pfisterer who had previously raced with the SCCA brought along an Austin-Healey 100-6 in place of his MG and Nick Caviluzzi a highly tuned Ford Thunderbird. Pfisterer broke the Jaguar stranglehold by winning the first race at Virginia Beach Speedway and then at Altamont Speedway, whilst the Ford Thunderbird bullied its way to victory at Williams Grove Speedway and Hatfield. Pfisterer’s consistent high-place finishes gave him the 1955 SCODA championship ahead of Nick Caviluzzi, with Stan Becker in the third spot. Despite Bill Claren winning a couple of races in his Jaguar, he could do no better than place fourth in the rankings.

By 1956, SCODA was an organization to be taken seriously as more and more drivers joined the club, bringing with them an array of machinery that would have graced many an SCCA race.

The number of races that took place has been impossible to verify due to a couple of factors. Firstly, there were now two classes of vehicles and in both classes there were “race winners.” Secondly, the press did not always report on the race meetings that took place. Adverts for forthcoming events meant little due to cancellations caused by inclement weather on the day.

Within SCODA there was an election for officials with Stan Becker elected as the 1956 president. Other officials elected were Fred Pfisterer, Nick Caviluzzi, Bill Boyd Hanauer, Jake Jacobs, and Pete Mourad.

Sixty-three members registered to compete in the races, and between them, they used seventy-five cars in the season. Two Chevrolet Corvettes started the season strongly, taking first and second places at Raleigh Speedway and Martinsville Speedway, though by June it was Jake Jacobs who was on the top spot of the podium. He had started the season in his MG-Cadillac, but then changed to driving a Jaguar XK120 using a Corvette engine, in which he won many of his races. It was suggested in the press that he had entered 28 races including heats and won 19 feature races. Whilst that appears excessive, his points tally for the season was nearly 200 above the runner-up, Fred Pfisterer, who won the under 1500cc section, so it was certainly a highly successful and profitable season for him.

At the 1957 AGM an important decision was made that in some ways would turn the fortunes of SCODA, though in hindsight, not for the better. With the confidence of two years of success and growth within the club, the SCODA Board of Directors voted to cut SCODA’s ties with NASCAR, and to sanction its own races. However, because of prior commitments to the 1957 program, some of the venues continued to have NASCAR sanctions and it would be another year before SCODA fended for itself. At least 13 events took place during the year including races at new venues: Reading Fairgrounds in Pennsylvania and Rutland Speedway in Vermont.

Bill Boyd’s introduction to the one-half-mile dirt oval at Rutland was one he would have wanted to forget as on the second lap of the feature race he was involved in a four-car accident in which his Miller-Corvette Special flipped over. The race was stopped and Boyd was taken to the hospital. Luckily he survived though his car was wrecked.

The highlight of the 1957 season was the performance of Charles Bettman in the under 1500cc section of the Club’s races. He entered 10 events and won them all driving a VW-Porsche Special, a feat that out-stripped the over-1500cc class winner Bob Ellis. However, Ellis gained more points to take the overall title by entering more races and consistently ending up on the podium.

Part 2: Changes Abound

With SCODA operating independently from NASCAR in 1958, it brought in a few changes for the season. It had long been debated within the club as to whether the cutoff point between classes of cars should remain at 1500cc. Although there was a strong feeling that it should remain that way, the board of directors decided that a change to 1600cc would be in place for 1958. The gesture turned out to be more significant than the reality, as there appeared to be precisely the same cars competing in each class as in 1957.

Two new venues were added to the program for the year, Danbury Fairgrounds, which started out as a dirt track but was upgraded by owner John Leahy into a one-third-mile asphalt oval, and Riverhead Raceway on Long Island under promoter Ed Hawkins’ banner. As well as having its own schedule of races SCODA was invited to attend a meeting at Soldier Field, Chicago, though the results of this race meeting did not count towards the SCODA championship.

Originally there were 14 planned races for 1958, but four were canceled due to bad weather. As a consequence, the available purse money diminished from $16,950 down to $12,350.

The first race meeting was held at the Orange County Fairgrounds located in Middletown, New York, where the feature race was won by Bob Barnett driving last season’s MG TD-Corvette, fending off Charles Bettman’s VW-Porsche Special. In the next race at Plainville Stadium, Bettman took his revenge by winning the feature ahead of Barnett, but Barnett came back strongly to win at Riverhead Raceway and Williams Grove Speedway.

SCODA’s inaugural race meeting at Danbury attracted at least 27 entrants and a crowd of over 3,000 spectators. A new name appeared on the winner’s step of the podium, Charles Blewett, who drove his Ford Thunderbird to victory ahead of Charles Bettman. It was also the first victory of the season for Pete Mourad when he drove his Jaguar XK120 Special to victory at Wall Stadium in July.

The decision was made by the SCODA Board of Directors to revert the car class split to 1500cc for the 1959 season, as it would appear that nothing had been gained in changing the format for 1958. It was also announced that there would be at least 18 proposed events taking place throughout the season, including four in the Mid-Atlantic states. As the season progressed, the number of events dwindled due to bad weather with Islip, Polo Grounds Speedway, and Fonda venues as three early victims.

Some members from SCODA attended an early season event at Langhorne Speedway, no doubt enticed by the $5,000 purse for the feature race. Bob Barnett took fourth place, a creditable performance against the likes of Carroll Shelby in a Cadillac Special, Loyal Katskee in a Ferrari, and Bob Brown in a Jaguar 3.4 Special.

A meeting at McLean County Raceway, Smethport was won by Walt Hennigar in his Corvette-powered Austin-Healey in late May, while Bob Barnett drove his well-used MG TD-Corvette to victory at Empire Stadium Raceway on June 11. Of the other known results for the 1959 season, Bettman won at Fonda in June, using a Porsche 550 RS Spyder in place of his VW-Porsche Special, and Bill Boyd completed a narrow victory in his Miller-Corvette Special over Bob Barnett at Plainville. In taking the second spot, Barnett accumulated enough points to become the new SCODA champion for 1959, the first championship he had won.

The 1960 season was the last where any race details were reported on in the press on anything approaching a regular basis. A further change in club regulations saw the establishment of a new racing formula to encourage production autos to be involved in the races. Four divisions had been made, large and small production models, and large and small modified versions.

The first meeting of the season was held at Seekonk Speedway, a one-third-mile semi-banked paved oval that had been operated by the Venditti family since its opening in 1946. After winning his 10-lap heat, Fred Luchesi went on to win the feature race finishing ahead of Barnett and Boyd. A trip to Old Dominion Speedway followed, where Bob Barnett claimed the honors ahead of Bill Boyd. The Fonda Speedway races were postponed from Saturday, May 28 until the following Monday night due to heavy rain. Boyd turned the tables on Barnett to take the victory. SCODA did turn up at Lincoln Speedway for the first time in July where Lynn Connor, driving a Jaguar Special, won the feature race ahead of Barnett, and Herb Fisher beat Bill Boyd at a meeting held at Fonda in July.

An appearance at Thompson Speedway was due, but no evidence of the event taking place was found. The second half of the season was chaotic, meetings at Old Bridge, Arlington Speedway, Westboro Speedway, and West Peabody Speedway were supposed to take place, though no reports or results came to light.

At the end of the 1960 season, SCODA had more or less automatically dissolved its activity. President Bob Barnett indicated that the unwieldy board of directors had seriously hampered the club’s operations. Rather than dissolve the club entirely, the board of directors had been dissolved and it was left to Barnett to re-organize operations on a more realistic basis. In 1961 there would be no SCODA representation at the oval tracks.

A limited race program did recommence in 1962 with meetings at Old Bridge Speedway (won by Ken Andrews in a Jaguar twice in the season), Wall Stadium, and Plainville Speedway taking place, and a meeting at Old Dominion Speedway having to be canceled due to persistent rain.

There were two possible reasons why information was difficult to come by in the following years. First, with a lack of club directors, too much pressure was applied on Bob Barnett in the early 1960s and his failure to communicate with the press or place adverts for the races led to an information blackout. Second, the press had lost interest in SCODA because its race program appeared to diminish. Either way, it was not a true representation of the facts as the scant information available would suggest. Large numbers of entries and races at the established venues for SCODA continued certainly up to 1969. Reports that the following drivers took place in competition are confirmed in the drivers standings for 1964: Steve Krisiloff was top, followed by Ken Andrews, Jack Bettio, Dan Brent, Warren Arhens, Ron Russo Jack Van Wettering, Bob Wagner, and Hans Kleban. From reading these names it was also obvious that the old guard of drivers had either taken a back seat or disappeared from the scene and a new batch of drivers had taken their place.

In 1965, Al Krisiloff was elected as president of SCODA, and the class structure was changed yet again. That year Al Loquasto was the Class A top driver in his Chevrolet Corvette Stingray ahead of Art Kijek driving an Austin-Healey Corvette, while Andy Swain headed Class B and Bill Claren Class C. Loquasto won races at Hagerstown Raceway, Lincoln Speedway, Catamount Speedway, and Evergreen Speedway. Towards the latter half of the season, the weather wreaked havoc on the race schedule. The meetings at Milton Speedway, Pocono, and Pine Bowl Speedway were all canceled.

So far as can be confirmed, there were SCODA races held at Albany-Saratoga Speedway, Williams Grove Speedway (twice), and Richmond State Fairgrounds during 1966, but details are sparse. Steve Krisiloff won at Albany and Al Loquasto took the victory at Richmond. Other races would have taken place during the season – Steve Krisiloff won the championship by 10 points from John Paschal.

There was more reported activity (albeit scant) for 1967. At the start of the season, races were scheduled for Hershey, Pennsylvania, Thompson Speedway, Connecticut, Berwick Beach, Pennsylvania, Airborne Park, New York, Stafford Springs, Connecticut, Orange County Fairgrounds, New York, Atlantic City Speedway, New Jersey, Nazareth, Pennsylvania, and Catamount, Vermont. However, a few changes were made as the season progressed, with known races taking place at Westboro Speedway, Plainville, Williams Grove, and Fonda.

Joe Paschal ended up as the top driver for the season with 1100 points, 190 more than second-place finisher, Fred Pfisterer, one of the founder members of SCODA. Paschal drove his Chevrolet Corvette Stingray to victories at Hershey, Nazareth, Westboro, and Stafford Springs, while Steve Krisiloff in his Austin-Healey-Corvette won at Fonda, Atlantic City, and Williams Grove.

According to a report printed in the Illustrated Speedway News, SCODA was inactive during the 1968 season, although it appears that several SCODA drivers did participate in races sanctioned by other organizations. Fred Luchesi and Bob Barnett appeared at Seekonk, and Barnett and Boyd at Atco Speedway, while Al and Ben Loquasto were entered at Harmony Speedway.

At the 1969 AGM, Bill Claren stepped down as president, his place being taken by Nick Caviluzzi, a long-time member and official of the club.

A number of race meetings did take place, including ones at Westboro Speedway (twice), won by Jerry Walsh in an Austin-Healey-Corvette and Mike Dee in a Chevrolet Corvette Stingray, Harmony Speedway where Joe Hesse claimed victory and Atlantic City Speedway, won by Woodie Bimm.

Beyond the end of 1969, no accounts of races were found, and no reports about SCODA club activities came to light. It is possible that SCODA ceased to function.

Should any reader have further information about SCODA I would be pleased to hear from them.

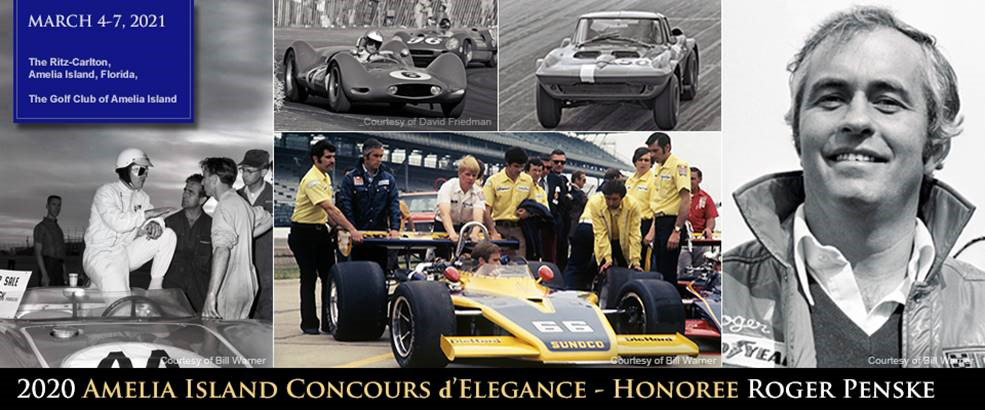

By Luis Martinez

“The best thing to do is to keep it quiet as long as you could.” Don Cox explained to an audience at the 25th Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, responding to the need to test, prepare, practice, and try out new ideas to improve performance or logistics before approaching The Captain. Roger Penske was of a mind to do things the right way within the bounds of competition rules. What Penske did not want is to do well only to be told by Scrutineering that his car was disqualified. Cox continued, “I saw that during a pit stop once in a while: a car would come in and if it had a flat tire you couldn’t get jacks under the car. So I thought, we have to have a better way to do it. We tried air jacks for the first time in 1974, ‘75, but I was afraid to show all that to Roger because I didn’t know what would happen. We practiced with the air jacks at the local Sunoco refinery, our sponsor. We went over there, we were practicing and we plugged in the air hose and the car jumped up. Roger looked at it, and he looked at me, and he said, “This is a great idea!” That was the start of air jacks on racing cars. All cars have air jacks now.”

Don Cox started his career as an engineer with Chevrolet’s Research and Development after graduating from General Motors Institute. He worked on many projects in Chevrolet R&D including Jim Hall’s Chaparral from 1965 to 1968. In March of 1969, Cox was assigned to work with Team Penske in the Trans Am program as an advisor while Penske was running two Camaros in Trans Am – the #6 piloted by Mark Donohue and the #9 by Ronnie Bucknum. In November 1969 when he joined Penske’s racing shop at Newtown Square, PA, he became the team’s first dedicated engineer. “I was chief engineer because I was the only engineer!” Cox grins. In that race shop, his responsibilities touched every part of Team Penske’s racing enterprise – the TransAm cars, Indy cars, World Endurance Racing Ferrari 512 and both Porsche 917-10 and 917-30 Can-Am Champions. Cox and Mark Donohue designed Penske Racing’s first custom-made race shop when the team moved from Newtown Square to Reading, Pennsylvania in 1973. In the words of Bill Warner, founder and chairman of The Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, Cox is “the man who saw it all.”

Cox reminisces about those days: “Looking back to 1969, I started with Roger when the shop was an old cinder block garage with 4,000 square feet and a crew of eight guys.” The Captain also reminisces about those early years: “One little shop at Reading, we were doing CanAm, we were doing TransAm, we were doing Indy, and I think we were doing IROC. All out of the same shop, think about that! All those disciplines out of one small shop in Reading, Pennsylvania. Again, why were we successful? All about the people, and to me, that’s the greatest thing we have – the colleagues and associates around us.” Including Don Cox.

1969 Camaro, 305cid ovh valve V-8, two four-barrel carbs, 440 bhp, 2,980 lb. dry, 4-speed transmission, Corvette brakes, Goodyear Blue Streak Racing tires. Caption source: Car Life Magazine, January 1970. Photo: Luis A. Martínez

The beautiful Sunoco Blue liveried Camaros, the #6 car and #9 car, were very successful. So why leave GM to go to Team Penske and switch efforts to American Motors? Cox explains: “Penske had been running Camaros for a couple of years so during 1969 I had worked for Chevy R&D with the Penske project. But the official position of GM at that time was “no racing.” Other than technical assistance, Roger could not get any financial support from GM. By November I began working full time for Roger on a new program – American Motors’ Javelin, to make it competitive.”

Although Penske was a Chevrolet dealer, his relationship with GM on the racing front had gone sour so he felt compelled to explore working with a different vehicle. Towards the end of 1969 Penske initiated talks with American Motors Corporation. The deal with AMC proved lucrative – two million dollars for the season employing the 1968-69 TransAm championship team.

Penske had seen Javelins only at a distance, so this was all new territory and full of risk, as he knew AMC had struggled with their Javelin entries while he, Donohue, and Revson had secured two championships. Penske decided to bring back Peter Revson to race the second Javelin with Donohue.

The Penske Racing stable included a plethora of Sunoco-clad Can-Am racers, with Mark Donohue, Peter Revson, and George Follmer among pilots. Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

There were some important carryovers from the Camaro program to the Javelin effort, and it paid quick returns. “In 1970, Penske carried the numbers six and nine from the Camaros to the Javelins,” explains Cox. “Up to that point, the Javelins were not competitive. Donohue drove the #6 Javelin and Peter Revson was assigned #9. In 1970, after winning the championship with Camaros in 1968 and 1969, our Team Penske Javelin team was only one point short of the championship in 1970, but we beat all the other Camaros. So our Penske #6 Javelin with Donohue was very successful in 1971, winning seven out of ten races and finishing second or third in the rest.”

When Cox arrived on the scene from Chevrolet Development he immediately started on a new suspension for the Javelin, which was bottoming out, running on bump stops virtually all of the time on track. Cox designed the entire rear end, which included the housing, axles, full-floating hubs, spool, linkage to locate the rear, and brakes. Cox pointed out to Penske the advantage of Girling disc brakes with Lincoln rotors.

Don Cox and 1971 Trans-Am champion AMC Javelin at 25th Annual Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance. Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

As for the engine, Penske needed to develop special AMC engine components as the 290 CID was down 100 horsepower to the competition. Team Penske looked to Traco in California for all the engines for the 1970 season. Regulation limited engine size to 305 CID. Traco managed to shrink a 360 to regulation by destroking, while still making over 400 horsepower comparable to Chevrolet. But then there developed a litany of blown engines on the track caused by oil starvation due to G-forces when braking. Team Penske devised a dual-pickup oil pump with the secondary pickup scavenging oil from the uphill side of the pan, where it was accumulating during hard braking. Then, Cox had to address the strain of the dual-pickup pump which was wearing out the drive gears on the cam, affecting the distributor running off of the same gears, which was throwing off timing as the cars got further into a race. Cox found a solution by drilling new oil passages to feed oil to the gears.

With the highly revised Javelin racer, Donohue won the first race at Lime Rock, then lost the next two to George Follmer driving a factory Mustang. Donohue went on to win the next six races in a row, clinching the TransAm championship in the 1971 season.

Don Cox (middle) explains his role spanning many years with The Captain at the sold-out, standing room only conference, “Team Penske – the Early Years”, in Amelia Island. Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

At this year’s Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, in a seminar entitled “Team Penske: The Early Years,” Roger Penske waxed reminiscent about Cox in the discussion panel: “The TransAm was exciting, and Don, you really don’t give yourself the credit because you worked at General Motors and we needed someone in engineering to come with us and really change it. I remember, we took on the Javelin project because they offered us a terrific deal financially and to take our drivers and take on another challenge. Cox walked in the shop and the first thing he said was: “We’re going to put these brakes on this car.” Think about this, all these factory teams, Mustangs and Dodges, and Don came in and fitted these brakes. Now I wasn’t sure whether they were going to work but they gave us a competitive advantage from the standpoint of having the brakes that nobody else had. So those were early wins. And I think he’s probably modest.”

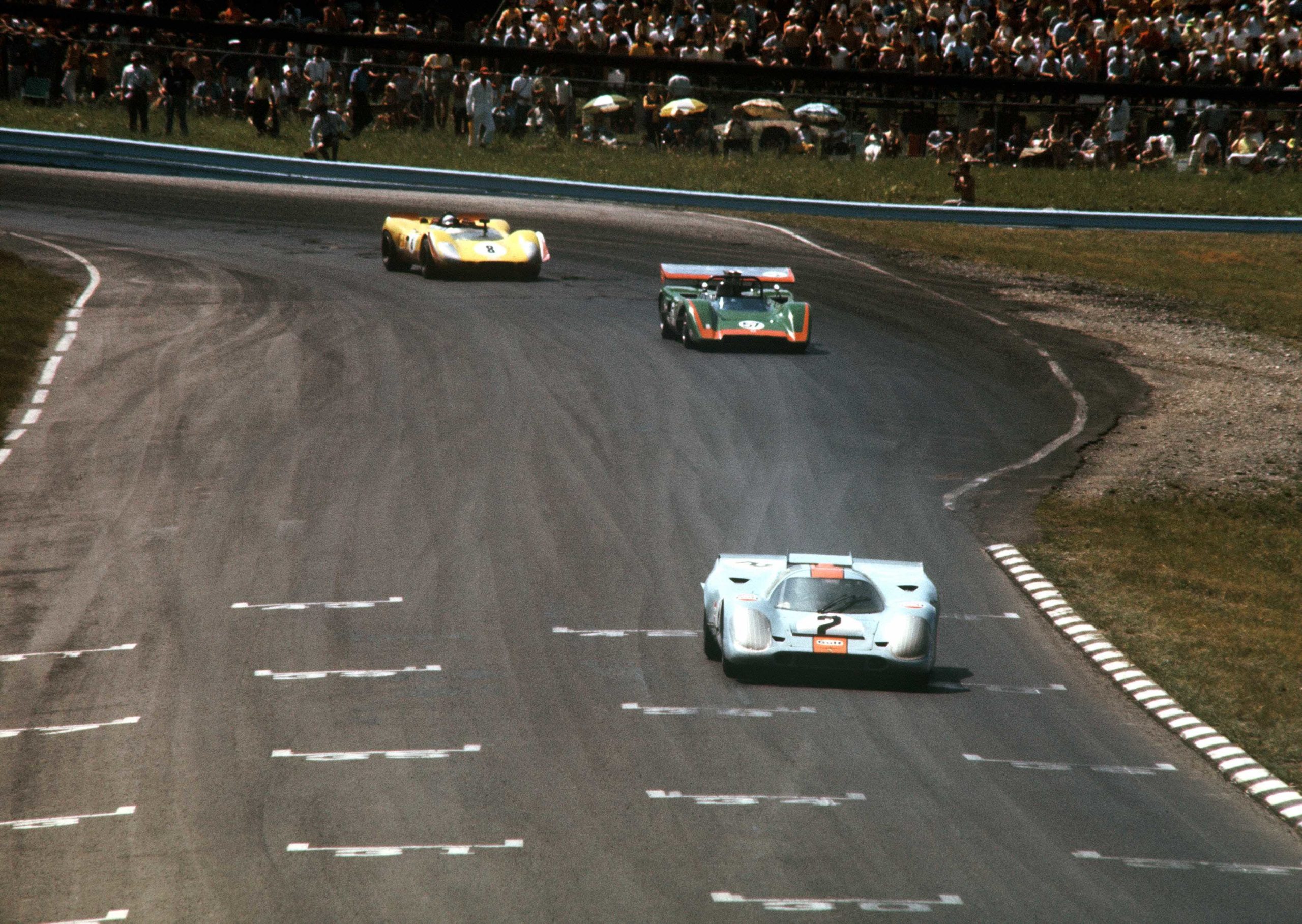

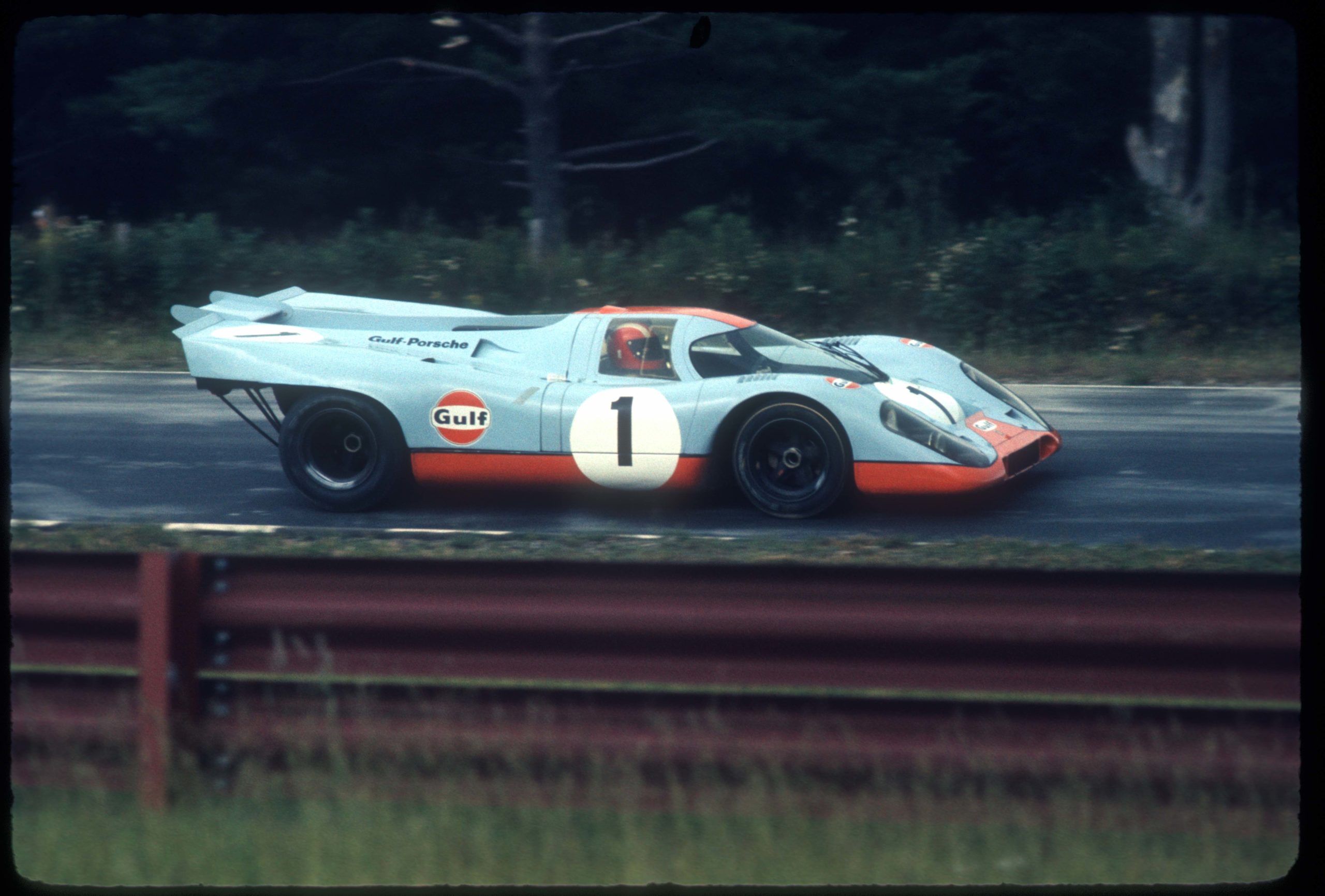

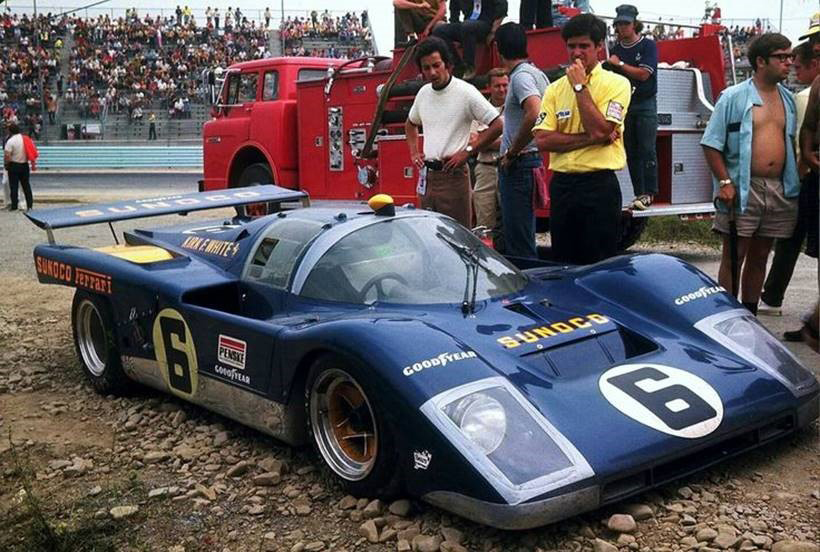

At the end of 1971, Penske was approached by Porsche to represent their marque in racing. What would prompt the Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG factory to seek the services of The Captain? Strangely enough – a Ferrari. There was this Ferrari 512S, chassis #1040 which had been lightly used in the CanAm Challenge. It was then purchased by a used Ferrari dealer in Philadelphia – Kirk F. White. In an effort to promote his fledgling car dealership, White approached Penske hoping Penske Racing would borrow the car and use Donohue to race it. Penske eventually agreed. Team Penske did substantial improvements to the 512 and, with sponsorship from White and Sunoco, Donohue drove it to appreciable success. “The reason that program got started [with the Porsche 917-10 and 917-30] was the success we achieved with the Ferrari 512M, a car that was owned by a local guy in Philadelphia [White]. As I recall, we did four long-distance races, and three out of four times we out-qualified Porsche with that car. Porsche decided they wanted to get into Can-Am racing in the U.S. and they were looking for an American team to actually run their cars in America. Because we had done so well with the 512M, compared to them, our team was one of the people they considered.”

Don Cox (yellow shirt) ponders his next move to keep Penske Racing’s Ferrari 512 in front of the Porsches. Photo: Gilles Robert, Pinterest.

At the Amelia seminar, with The Captain sitting in the front row, Cox laid out the real story: “We [Penske, Donohue and Cox] ended up going to Germany to talk to them [Porsche] about putting that deal together. I don’t know if Roger knows some of this. During the trip, Roger told Mark and me, “Now, you guys keep your mouth shut. I don’t want you to screw up this deal.” He said, “I’m going to go make this deal with Porsche.” So Mark and I just looked at each other. And when we get there, they have all these test cars to drive, and they have all this stuff to show us, and it was really an informative session with their engineers. At one point I got Helmut Flegl off to one side; he was their engineer who was going to be the head of this project that Porsche had assigned him. So I asked him, “What kind of wing are you going to have on this thing, on this new Porsche?” He looked at me and he said, “Porsche thinks wings are for airplanes.” And…. end of conversation, because I didn’t want to screw up this deal.” Penske and the audience laughed in understanding.

Donohue, Penske, Don Cox and Helmut Flegl at Weissach with normally aspirated test of 917/10 on that first trip to Germany. A much bigger wing was developed by Donohue and Penske. Photo: Porsche, Caption: Dean’s Garage

Cox continued explaining the saga: “Roger apparently made a deal so he said to me and Mark, “Okay, I think we got a deal.” So we got on a plane, Mark and I, to fly back to New York, and Roger went off somewhere else. All the way home, on the plane, we are talking and I said to Mark, “You know, I didn’t get a very good reception on that ‘what kind of wing are you going to have?’ thing. Now don’t forget the vacuum cleaner car [Chaparral 2J] was in existence in 1970. Anyway, I was thinking maybe they don’t want to do wings, maybe they got some other idea. Long story short, we didn’t even leave the airport in New York, we went back to Lufthansa and went back to Germany. We called Flegl and said, we have to have a meeting. So we had a meeting!” With a grin and a wink, Cox reveals – “Roger didn’t know this. We had a meeting with Flegl and he was a very, very bright guy, but he was new to motor racing, so we sat down and we explained everything about why have a wing, what it does, and it doesn’t matter that it has a little bit of drag, that you can sacrifice a little speed on the straightaway if you can gain significantly in the corners. And so you can see him coming right up to speed really quickly, and he said, “Okay, I will talk to the higher-ups.” About a week later we got a response on a Telex machine and it said ‘WE WILL HAVE WINGS.’ It all ended well, but it’s funny how it started.”

The Penske program for 917s was enormously successful. Starting with the L&M Cigarette liveried Porsche 917-10, Porsche earned their first CanAm Challenge Cup in 1972 with Donohue and George Follmer. Powered by the 5-liter air-cooled flat-12, the 917/10 was rated at 850 horsepower. That was a lot to handle even for the experienced Mark Donohue, who after an accident could not finish the season for the 1972 CanAm title. The white wedge became one of the most recognizable racecars in history.

Porsche 917-10 K Serial 003, driven by Can-Am Champion George Follmer, dominated the ’72 Can-Am series taking 1st at 5 of 9 races Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

Then came “the beast.” Considered by some the most powerful racing car ever to set tire to pavement, the 1973 Porsche 917-30 towered above all. This was a reliable rocket with a turbocharged air-cooled flat-12 engine of prodigious capacity. Its power ranged between 1100 and 1580 horsepower which Donohue could adjust from the cockpit. Weighing a scant 1,800 pounds dry, this CanAm contender, in its world-renowned blue and gold Sunoco livery, could sprint from zero to 200 miles per hour in 10.9 seconds. Top speed is estimated at more than 260 miles per hour, but who would dare test the limits?

Mark Donohue’s Porsche 917-30, at Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance 2020. Donohue turned fastest closed-circuit lap in world history at Talladega Superspeedway, AL, average speed of 221.120 mph. on August 9, 1975. Photo: Luis A. Martínez

Cox’s first experience with Indy racing was in 1970 with Penske’s Lola T150, the #66 car. It finished in second place. Cox explains his involvement: “For 1971, Penske switched to McLaren. We wanted to be very involved in the design so we contracted to build the cars in England, designed by McLaren with Team Penske input. In 1971, Donohue won the Pocono 500 with that car. In 1972, I was the engineer with Donohue in the #66 car, the McLaren M16B, and on May 27 we won Roger’s first of an incredible string of Indy races.”

The Captain adds his touch to the Indy stories, “The air jacks, think about that. We brought air jacks to racing. Going to Indy and these guys with these hammers, and trying to get the wheels off, and these jacks, and it was a joke. Wasn’t it? We were a little too sophisticated! They called us the college boys, remember? With the crew hair cuts and the polished wheels and the yellow floors. That’s what our reputation was at Indy. Well, 18 races later I think some of those guys got their garages better.”

Roger Penske (kneeling) and the crew of Mark Donohue’s Sunoco McLaren in 1971. Don Cox is standing 4th from left. Photo: Indianapolis Motor Speedway photo.

The Captain has been building his reputation for decades, and it’s a lot more than crew cuts, yellow floors, and polished wheels. Here’s a point of view from an uninvolved racing fan named Bob Collins. Bob was attending college in Adrian, Michigan. One weekend in the spring of 1977 he was bored in his dorm room, so he went to Michigan International Speedway to watch race cars test and tune. Bob parked his 1975 Olds Cutlass at the steel gate of a service road and sat on the hood of his car to watch the action. A well-appointed late-model sedan approached the gate and the driver, seeing Bob, looked discomfited. The gentleman then asked Bob what he was doing there, pointing out that this was private property. Bob responded, “Well, I was in my dorm room, really bored, everyone is gone, so I came over here to see the cars. I love racing cars. I’m from upstate New York and I’ve been to races at Watkins Glen.” A brief conversation ensued, and unexpectedly the gentleman went and unlocked the gate and motioned to Bob that he could drive his Cutlass for one lap around the 2-mile D-shaped track. That gentleman could offer such a gesture, unthinkable today, because he owned the track – Mr. Roger Penske.

Bottom center color photo of 1973 Indianapolis 500, #66 car Penske Eagle/Offenhauser with Mark Donohue. Penske is second from left, Don Cox is 4th from left with jacket over his left arm. Photo: Bill Warner Archives

Cox maintained a full time working relationship with Penske for seven years. But it didn’t end there. “I left the race shop in ’76 after Mark Donohue died in Formula One practice at the Österreichring in 1975.” Cox relates, “But I kept working on projects and races with Roger until 1989, a total of 20 years. During my 20 year involvement with Penske Racing, I saw Penske accumulate seven Indy 500 wins.” Penske Racing went on to win an astounding total of 18 Indy 500s.

Today, still living in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Cox remarks on the many years with Penske: “Thinking back as far as my work on the Camaros, or the Javelin, or in Germany with Helmut Flegl and the 917, it all ended well – but it’s funny how it all started.”

Author Luis Martinez and Don Cox at Amelia Island Concours, March 8, 2020. Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

While people more readily associate American race drivers as appearing in Europe after World War II, it is worth reflecting on one individual, who through circumstances that were not of his own making, took up the mantle in the 1930s.

This was Whitney Willard Straight, born in November 1912 in New York. His parents had wealth beyond the dreams of most people, an asset that Whitney put to use in setting up his own race career as well as his own company. His father died of Spanish Flu, and his mother, an heiress in her own right, remarried agronomist Leonard Elmhurst. In 1925, the family moved from America to Darlington House in Devon, England. The young Whitney attended the progressive school that his parents had founded before going to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied philosophy.

This was Whitney Willard Straight, born in November 1912 in New York. His parents had wealth beyond the dreams of most people, an asset that Whitney put to use in setting up his own race career as well as his own company. His father died of Spanish Flu, and his mother, an heiress in her own right, remarried agronomist Leonard Elmhurst. In 1925, the family moved from America to Darlington House in Devon, England. The young Whitney attended the progressive school that his parents had founded before going to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied philosophy.

While at Trinity College his thoughts turned to motor sport and he purchased his first car, an Alvis Silver Eagle. He did not race this car, but purchased a second vehicle, a Riley Nine (more commonly referred to as a Brooklands Riley), and it was this car that he entered at Shelsley Walsh, his first competitive event, in July 1931. Straight finished in third place in his class behind two other Rileys. It was here that he became aware of Dick Seaman who was attending Trinity College, and was also racing a Riley. Straight and Seaman were to become very close friends over the coming months.

Three more meetings were attended before the end of 1931, two at Brooklands and one at Southport. In each of these races, he finished well up in the classification but realized that he needed something more powerful if he was to really compete for honors.

His first race of 1932 was to see him travel to Sweden for the Swedish Winter Grand Prix, the only foreign racer to make the journey. He was embarking on an extensive program of racing that would occupy him fully over the next few years. The circuit was huge, nearly 30 miles over frozen roads in an area near Lake Rämen to the west of Stockholm, which the drivers had to cover eight times. Straight soon had trouble and was well behind after two laps, at which point he decided to drop out of the race.

Straight purchased a 2-liter non-super-charged GP Bugatti which he used at Brooklands. He came in first overall on a handicap basis, but was still not satisfied. As a result, Straight bought the ex-Birkin 1931 2.5-liter Maserati and used it in the two remaining races of the season that he had entered. He finished in the second spot in the Lightning Mountain Handicap losing out by one-tenth of a second, in what was described by motoring correspondents as one of the most exciting Mountain races ever.

1933 proved to be a busy year for Straight. As well as attending eight meetings in England, he was present at Rheims, Stockholm, Pescara, Comminges, Albi, Mont Ventoux and Monza. There were victories at Brooklands, Brighton, Nottingham, Shelsley Walsh and Mont Ventoux in the Maserati M26 as well as a victory in the 1100cc race in Pescara in an MG K3 Magnette. In the main event at Stockholm he drove Bernard Rubin’s 2.6-liter Alfa Romeo, before flying himself and his mechanic Berk Harris to Pescara in his own airplane. Mont Ventoux was the highlight of his season when the Maserati 26M broke the track record with a time of 14min 31.6 sec, taking no less than 40 seconds off Rudi Caracciola’s previous figure in a Tipo B Alfa Romeo.

The MG K3 Magnette was also driven to victory in a squall of rain at Brighton by Psyche Altham, and entered a hillclimb at Shelsley Walsh. She did not record a time due to a problem with the MG’s carburetor, but Psyche also raced the car at Brooklands finishing third in the Ladies’ Mountain Handicap race. After the 1933 season she disappeared from the motorsport scene. (It was reported in one motoring magazine that she was Straight’s fiancee, but in 1935 he married Lady Daphne Margarita Finch-Hatton.)

The latter half of 1933 was to witness some interesting developments for Whitney Straight, as he decided not to remain at Cambridge for his third year of studies but to take up racing more professionally.

He moved from Cambridge to London to form Whitney Straight Limited, and the Company was registered in December with a nominal capital of £5000, the directors being Whitney Straight, Reid Railton, and William Lambert. Having done that, he wanted to increase the number of cars to race and was interested in purchasing three Alfa Romeo Tipo B monopostos. However, Alfa Romeo could not supply the cars so Straight went to their rivals and ordered three of the latest 2.6-liter 240 bhp 8CM Maseratis which cost him £6,000. Giuilio Ramponi was appointed head mechanic and three trucks were obtained to transport the racing cars. Hugh Hamilton and Buddy Featherstonhaugh were contracted to drive the cars along with Whitney Straight for the 1934 season.

It turned out to be a season of mixed fortunes, starting well with a win at Brooklands by Straight in a Maserati 8CM, though come two weeks later both of the Whitney Straight entries retired from the race at Tripoli. Casablanca was an improvement with Straight taking fourth place but Hamilton went out on lap 42.

It wasn’t until the Albi Grand Prix on July 22 that the Whitney Straight team was to savor success again, with Hamilton winning in the Maserati 8CM and Featherstonhaugh coming second in the well-used Maserati 26M. This meeting was followed up at Klausen with a win for Hamilton in the under 1100cc race in the MG K3 Magnette, and again at Pescara two weeks later. A win at the Berne race on August 26 by Dick Seaman in the MG K3 Magnette was poor consolation for the tragic accident that happened in the Swiss Grand Prix when Hugh Hamilton was killed driving a team Maserati 8CM car, crashing into a tree on the final lap of the race. The accident put a dampener on the remainder of the season, though there was one last flourish at the South African Grand Prix when Whitney Straight brought his Maserati 8CM home in first place.

It was a fitting end to the season, and a fitting end to Whitney Straight Limited, as Straight had decided to retire from motor racing. One of two reasons was that the decision was undoubtedly influenced by the untimely death of Hugh Hamilton, and secondly, Straight had found to his cost that racing was a very expensive hobby. At the end of the 1934 season, all things taken into account, Whitney Straight Company had lost £2,775. Wealthy though Whitney was, he realized that to continue into another season would be unsustainable.

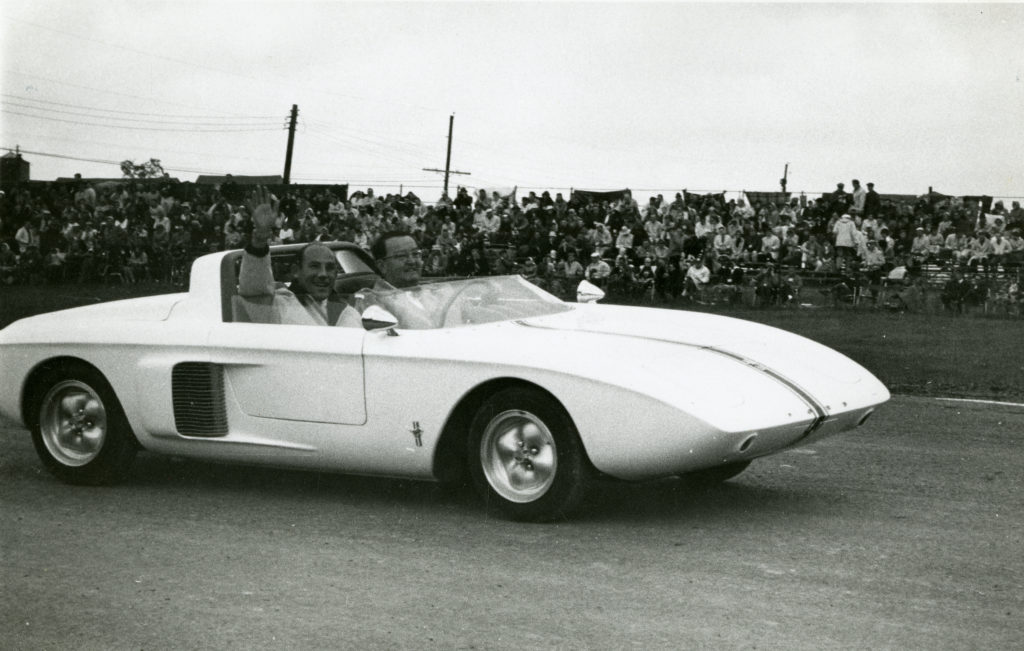

This year’s Grand Prix Festival in Watkins Glen honors Mustang, the original American “pony car.” Ford Motor Company developed the experimental version of the Mustang in 1962 to test new innovations in design and styling, later producing the wildly successful street car that would carry the name and the model’s popularity through almost six decades.

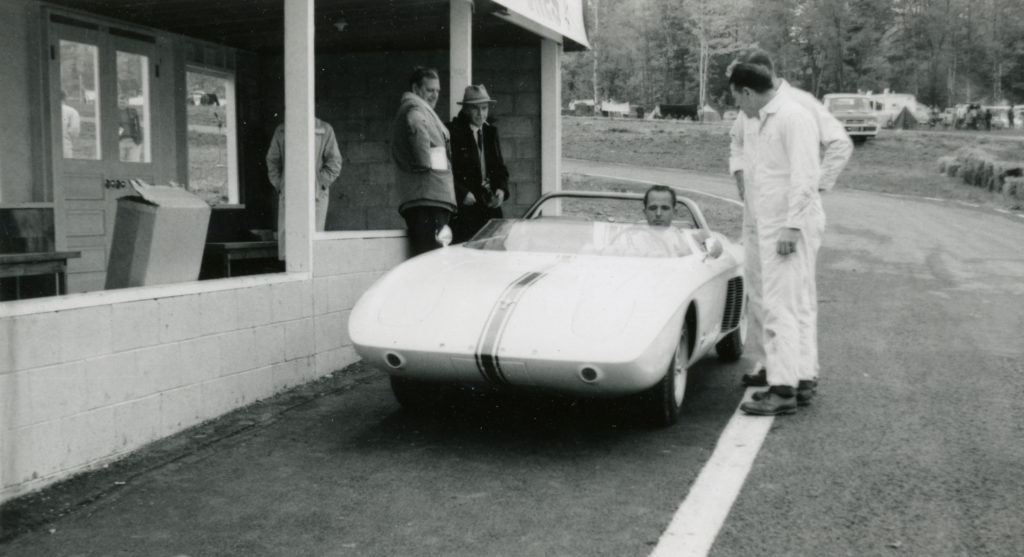

The new Ford Mustang prototype leads the Drivers’ Parade of Honor at the United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen in 1962.

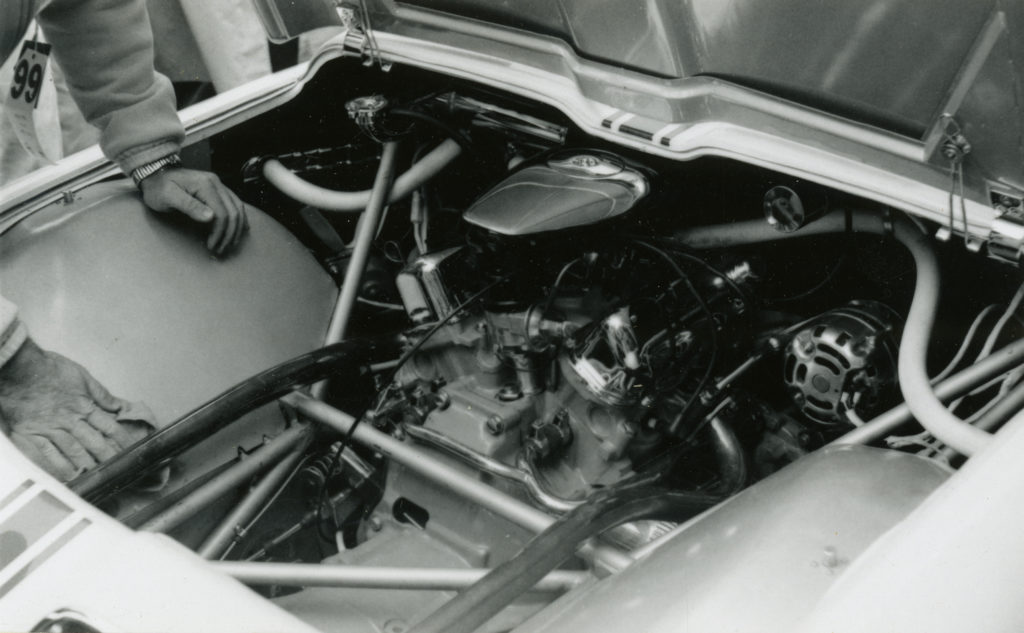

Ford introduced the two-seater, prototype Mustang roadster at the United States Grand Prix in October of 1962. The accompanying photographs from the Bill & Ginny Close collection in the Center’s archive depict the new Mustang leading the drivers’ parade, in the pits, and on the track. One shows the 60-degree, mid-mounted V-4 1500cc Cardinal engine with four-speed transaxle. Course marshal Charles Lytle with Sir Stirling Moss, the race’s honorary starter, riding shotgun, led the parade of Ford Galaxies carrying Formula One drivers from around the world. Popular racer Dan Gurney put the Mustang through its paces on the road course, showing off the design and performance while achieving speeds of over 100 m.p.h., in a non-competitive demonstration drive.

The prototype’s development by a talented group of company engineers and stylists marked Ford’s renewed interest in racing and performance. Its debut heralded the success of Ford’s “Total Performance” program, a commitment of corporate resources to motorsports competition that would allow the manufacturer to dominate racing in the 1960s. It tested the feasibility of an affordable, sportier car in a growing market of eager, young buyers.

The fully-functional, hand-built prototype or Mustang I varied greatly from later models. The “startling,” one-of-a-kind sportscar was fabricated by Troutman & Barnes, a race car shop in Culver City, California. Weighing in at 1200 pounds, it was aluminum bodied, tube framed, with an independent suspension, front disk brakes, and a 90-inch wheelbase. It had a built-in roll bar and 13-inch cast magnesium wheels. It was liveried in American racing colors of blue and white, with the famous running pony emblem on the hood.

This Ford Motor Company film about the creation of the prototype narrates the process from the drawing of the original design, constructing the frame, showing the body as it is sculpted in clay and fabricated in fiberglass and aluminum, through the testing process, and its public debut at Watkins Glen. Bill France Sr. makes a cameo appearance watching the Mustang’s run at Daytona.

The original prototype is preserved as part of the automobile collection at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

Ford Motor Company partnered with the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation, the track’s managers, from the first Formula One race in 1961. The Glen was used as a venue for publicity events for the manufacturer. The Mustang II, a 4-seater concept car, debuted at the United States Grand Prix in 1963, the year after the experimental version was first introduced. Mustang was the official car of the Glen from 1964 to 1967, with 23 Mustangs made available for the use of Formula One teams during their visits. Mustangs paced races at Watkins and the Indianapolis 500.

The production model, four-seater Mustang coupe launched in April 1964 at the New York World’s Fair sold 1 million cars in less than two years, the most successful launch for Ford since the Model A in 1927. They were the hottest thing around and virtually unobtainable the first summer with as much as a 3-month backlog on orders. Initial research revealed more than half of Mustang buyers in 1964 were between 20 and 34 years of age and 40% made $5000 to $10,000 per year at a time when the median family income in the United States was $6,600. With the launch of the Mustang, Ford successfully targeted a younger, single, female demographic, providing an affordable, compact coupe with style and performance.

Driven by Cameron Argetsinger, this 1964 Mustang served as the official pace car during the Glen 500 and other local races.

Come to the Festival to celebrate Mustangs of all eras. Enjoy the appealing personality of the early models described by the manufacturer as “demure enough for church-going, racy enough for the dragstrip, modish enough for the country club.”

In a bygone era on the African continent, when most southern African countries were colonies under the control of European powers, “Grand Prix” motor racing for sports cars flourished for a brief period of time.

One such country involved was Angola, a Portuguese colony, and it was the Portuguese government that encouraged this action as it wanted to expand motorsport in order to build a sense of unity in its empire at a time when there were signs of unrest.

There was already thriving local motorsport in the capital of Luanda and some of the provinces. The main organization representing the sport was the Automovel e Touring Clube de Angola, with many monied members mainly connected to the tobacco and oil industries. The president of the club, Acacio Pereira de Matos, regarded as a faithful representative of motorsport in Angola, was given the responsibility of organizing the event. His position as a member of the colonial bourgeoisie and from an old family in the province linked to Norton de Matos, governor-general of Angola, stood him in good stead for the task ahead.

There was already thriving local motorsport in the capital of Luanda and some of the provinces. The main organization representing the sport was the Automovel e Touring Clube de Angola, with many monied members mainly connected to the tobacco and oil industries. The president of the club, Acacio Pereira de Matos, regarded as a faithful representative of motorsport in Angola, was given the responsibility of organizing the event. His position as a member of the colonial bourgeoisie and from an old family in the province linked to Norton de Matos, governor-general of Angola, stood him in good stead for the task ahead.

Following the example set in the Belgian Congo the previous year, the motor race was arranged to be run on a street course that measured 3.429 Km and wound its way around the streets of Luanda. It was known as the Fortaleza Circuit, with the main straight going along the Avenida Marginal.

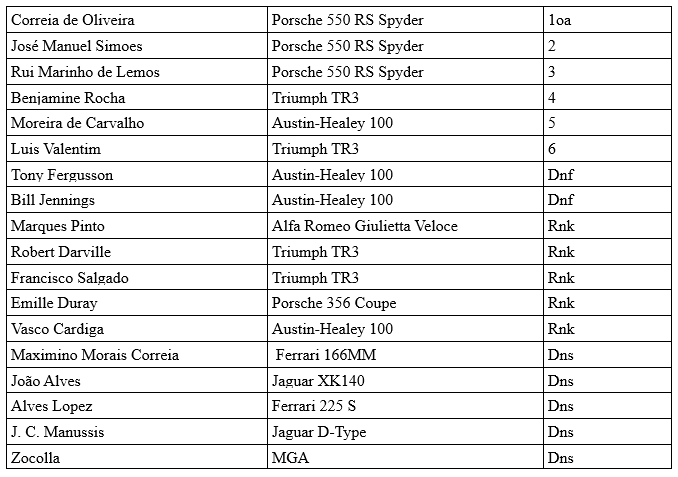

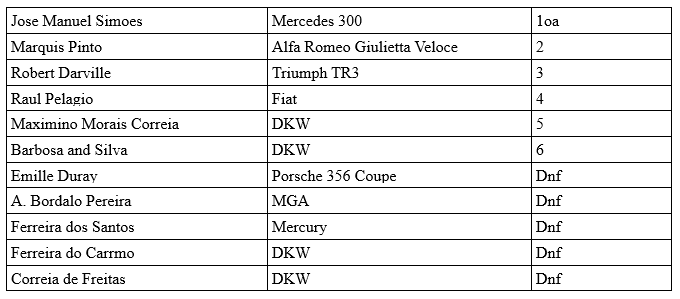

To run in conjunction with the Grand Prix, a second race was established for mainly local drivers with cars of lesser power. This race, known as the Taca Cidade was held the day prior to the Grand Prix and produced a field of eleven cars. The race distance was substantially shorter than the Grand Prix and was won by the Portuguese driver Jose Manuel Simoes driving a Mercedes ahead of Marquis Pinto and Robert Darville. Unfortunately, the event was not covered in any depth by the newspapers in Angola, and subsequently, some information is vague.  Entries for the Grand Prix race were received from Portugal, South Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, and Belgian Congo, as well as a couple of local drivers from Angola.

Entries for the Grand Prix race were received from Portugal, South Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, and Belgian Congo, as well as a couple of local drivers from Angola.

The better-known and more established drivers turned up with Porsche 550 Spyders, transported from Portugal by TAP airline, while Austin-Healey and Triumph TRs were the choice of most other drivers. There were two Ferraris transported to Luanda from Portugal, purchased by the ATCA for the use of the two outstanding Angolan drivers, Maximino Morais Correia and Alves Lopez. The Ferrari 166MM and 225 S models had been raced in Portugal in the early 1950s but since then had languished in a garage, so were not in the best of condition to be put through their paces again.

As far as can be established, eighteen cars were entered for the race – though only 13 starters can be accounted for. One driver, J. C. Manussis from Kenya, had an accident on his way to Luanda in the truck carrying his Jaguar D-Type and was forced to return home.

As far as can be established, eighteen cars were entered for the race – though only 13 starters can be accounted for. One driver, J. C. Manussis from Kenya, had an accident on his way to Luanda in the truck carrying his Jaguar D-Type and was forced to return home.

Practice for the Grand Prix was started on Friday at 7:00 a.m. for an hour, so as not to interfere with local business. The roads closed at mid-day for the Taca Cidade race. Within the practice time allocated, the two Ferraris were side-lined with mechanical issues, and with few spare parts and no trained Ferrari mechanics, the cars were withdrawn from the race. Likewise, both João Alves and Zocollo suffered malfunctions with their cars and failed to make the starting grid.

Portuguese driver Correira De Oliveira placed his Porsche on pole and pulled into the lead, a position he maintained until the end of the 70-lap race. Followed closely by Simoes for the first half of the race before he eased up when it became obvious to him that he could not pass, Oliveira contented himself with second place at the finish. Lemos, a navigator on TAP aircraft and part-time driver finished in the third spot. South African driver Tony Fergusson in his Austin-Healey had held the third spot but had to retire on lap 33.

One potentially serious accident happened in the race when South African Bill Jennings, driving an Austin-Healey, skidded and climbed the curb, plowing into a pile of hay bales. Luckily for him, track marshals were on hand to rescue him. Despite the swift action of the marshals, Jennings was hospitalized for a week in Luanda to recover from his injuries. Even though he failed to finish due to his accident the race officials classified him as finishing in seventh place, based on the distance covered.

One potentially serious accident happened in the race when South African Bill Jennings, driving an Austin-Healey, skidded and climbed the curb, plowing into a pile of hay bales. Luckily for him, track marshals were on hand to rescue him. Despite the swift action of the marshals, Jennings was hospitalized for a week in Luanda to recover from his injuries. Even though he failed to finish due to his accident the race officials classified him as finishing in seventh place, based on the distance covered.

Written by Luis Martinez

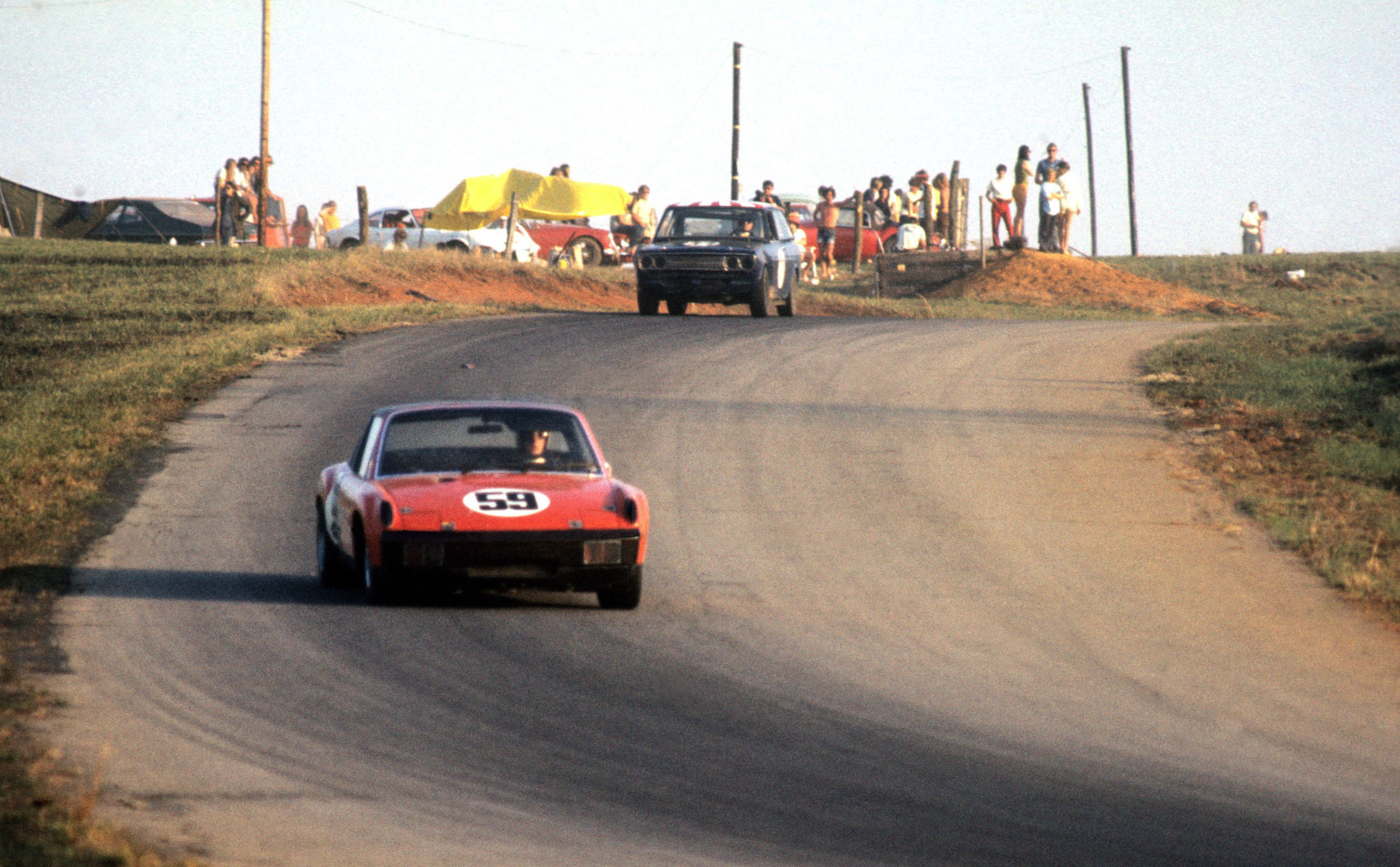

This story begins in 2011 when I was invited to work as a Staff Track Instructor at Monticello Motor Club (MMC), in Monticello, NY. But this story is not about me. It is about a group of very young and talented drivers who have clawed their way to podium finishes in competition against the world’s finest sports car racers.

During the six seasons I worked at Monticello I had the opportunity to meet many gifted young drivers. Who are these people that occupy mind share when I’m in places like Daytona, Watkins Glen or Sebring? Some who come to mind include Patrick Gallaher, Jason Lare, Corey Lewis, Stevan McAleer, Jason Rabe, Aurora Straus, Alex Wolenski and more. I find it remarkable that this car club has become a developmental platform, able to launch such a good group of drivers into professional racing ranks. Over the course of several years since I worked with them, these drivers have registered for races under various sanctioning bodies, including IMSA, Mazda MX-5 Cup, Continental Tire Challenge, Weathertech, Michelin Endurance Cup, Lamborghini Super Trofeo and others.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Twelve Hours of Sebring. The Sebring 12- Hours entry list for 2022 consisted of 53 cars in five categories. Replacing GTLM (factory-affiliated racers) this year is the GTPro. These are professional drivers in highly tuned but recognizable cars, some with factory assistance. There were 11 GTPro cars on the grid this year, including Acura NSX GT3, Aston Martin Vantage GT3, BMW M4 GT3 (2 entries), Corvette C8.R, Ferrari 488 GT3 Evo, Lamborghini Huracan GT3 Evo, Lexus RC F GT3, Mercedes Benz AMG GT3 Evo and Porsche 911 GT3.R (2 entries).

Another sports car class is the GT Daytona, which invites developing drivers – but many make a living racing and coaching racers – so it’s still a very select group. There were 17 GTD privateer entries piloting Acura NSX GT3, Aston Martin Vantage GT3, BMW M4 GT3, Ferrari 488 GT3 Evo, Lamborghini Huracan GT3 Evo, Lexus RC F GT3, McLaren 720S GT3, Mercedes Benz AMG GT3 Evo and Porsche 911 GT3.R. For marketing reasons, entries in the GTD category purposely retain visual characteristics as close to showroom stock as possible.

In total, 28 of the 53 entries were recognizable sports cars running in GTPro and GTD. The other 25 entries are never seen outside a racetrack.

Resembling spaceships – there were seven entries in Daytona Prototype International (DPi) powered by a Cadillac V-8, Acura V-6 or Mazda V-4 Turbo which can take them up to 200mph. The second class consisted of eight Le Mans Prototype 2 (LMP2) with similar weight, powered by a Gibson V-8 which lets them see about 190 mph. In the third tier there were 10 Le Mans Prototype 3 (LMP3) which can reach 180mph powered by a Nissan V-8. These closed cockpit cars are the most sophisticated closed-wheel racers in the IMSA series.

At this event, my focus was on three drivers that I worked with at Monticello – Pat Gallagher, Corey Lewis and Stevan McAleer. Responding to questions about their racing history to date, this is what they had to say about their journey to the top tiers of professional sports car racing.

In 2013, when he was only 20 years old, Patrick’s job at Monticello was Staff Track Instructor. One could reasonably ask – how can a 20-year-old be hired as Track Instructor at a venue where the members are wealthy – and much older than Pat? Ari Straus, CEO and Manager of Monticello Motor Club responded: “The nature of track instruction at Monticello is primarily to help with novice drivers. The benefit is that these same instructors also continue to coach and move club members and their guests from novice to solo, then to intermediate, and even to ‘gentleman racers’ who receive coaching services from our instructor team. As a result of our race coaching, Monticello has become the number one incubator for gentleman drivers at pro-level competition and reciprocally the number one organization for racing coaches to find opportunities to coach as they are surrounded by gentleman drivers.”

Piloting the copper-colored McLaren 720S, the 59-car at The Bumps, Patrick Gallagher’s driving skills started to shine 15 years earlier in the Mid-State Ohio Kart Club where he won the 2007 Championship. Fast forward to 2022, Pat had notched a Mazda MX-5 Cup championship. He also won the IMSA Continental Tire Sportscar Series in a GT4 Ford Mustang for Multimatic Motorsports at Watkins Glen International. After co-driving a Ferrari 458 in a Historic Sportscar Racing event at Sebring in 2019, Pat was now in Sebring with co-drivers Jon Miller and Paul Holton in the Crucial Motorsports McLaren 720S GT3. Helping his passion for sports car racing, Patrick brings his degree in Industrial and Systems Engineering from Ohio State University to bear on the track.

Pat drove the same McLaren 720S at the Daytona 24 in January and now he was piloting at the Sebring 12, so how is that McLaren holding up? “The GT3 car has so much more grip and power, and it’s lighter [than a GT4 car] so it brakes better. Everything is turned up 20% better than a GT4 car. The McLaren is really good in the high-speed corners like Turn 1 at Sebring and the bus stop at Daytona. If your car’s strong suit is high-speed corners that’s where you have to attack.”

Endurance racing requires extraordinary stamina. To run a 2-hour stint, what levels of fitness are needed? Pat replies: “It’s like 140 [Fahrenheit] inside the car. I’ve been working with a trainer in North Carolina. It doesn’t make me any faster over a lap, but the fresher you are at the end when it’s 10 laps to go and it’s kill-time – you got to be ready to rock.”

As Pat seeks to inspire younger men and women considering racing, he wants them to remember this: “I’m a racer, a real racer, my Dad was a racer, my grandfather was a racer. I grew up racing, that’s all I am doing.” Pat emphasizes the need to have an all-consuming affinity and focus in order to make it. “It’s a ladder system. I went through the Mazda Motorsports ladder system. I wouldn’t be where I was without them.” Pat lets readers know that it’s a small world in racing so it’s important to meet people. “I knew I could drive IMSA for a long time. It’s getting everyone else to believe it. I’ve known I could do that but getting yourself in that position [to be seen] is the hard part. I knew I could do it because I was racing some really, really good guys. When I started racing Michelin Pilot Challenge and you’re racing a lot of the same guys who are running in Weathertech in IMSA, when you’re in a GT4 car racing against those guys [in GT3, a higher class] and running up front, being super competitive – all I needed is to get a chance to get in the big show.”

What is Pat’s goal post at this point? “Winning at the Weathertech level is step number one. Winning the Rolex 24 [Hours of Daytona] is step number two. I want to check off all the big races – the Sebring 12 Hour, the Petit Le Mans, and then obviously a Weathertech championship.”

Does Pat have advice for young racers? “Ask yourself if you really, really, want to do it, and if the answer is yes, then do whatever it takes. You [Luis] saw how we lived when we were at the crash house [in Monticello]. It was the best time I never want to have again! Then you have to do better at making relationships. It’s relationships, relationships, relationships. If there’s a car that doesn’t have a driver, and they don’t know who you are then they’re not going to call you.”