By Luis Martinez

“The best thing to do is to keep it quiet as long as you could.” Don Cox explained to an audience at the 25th Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, responding to the need to test, prepare, practice, and try out new ideas to improve performance or logistics before approaching The Captain. Roger Penske was of a mind to do things the right way within the bounds of competition rules. What Penske did not want is to do well only to be told by Scrutineering that his car was disqualified. Cox continued, “I saw that during a pit stop once in a while: a car would come in and if it had a flat tire you couldn’t get jacks under the car. So I thought, we have to have a better way to do it. We tried air jacks for the first time in 1974, ‘75, but I was afraid to show all that to Roger because I didn’t know what would happen. We practiced with the air jacks at the local Sunoco refinery, our sponsor. We went over there, we were practicing and we plugged in the air hose and the car jumped up. Roger looked at it, and he looked at me, and he said, “This is a great idea!” That was the start of air jacks on racing cars. All cars have air jacks now.”

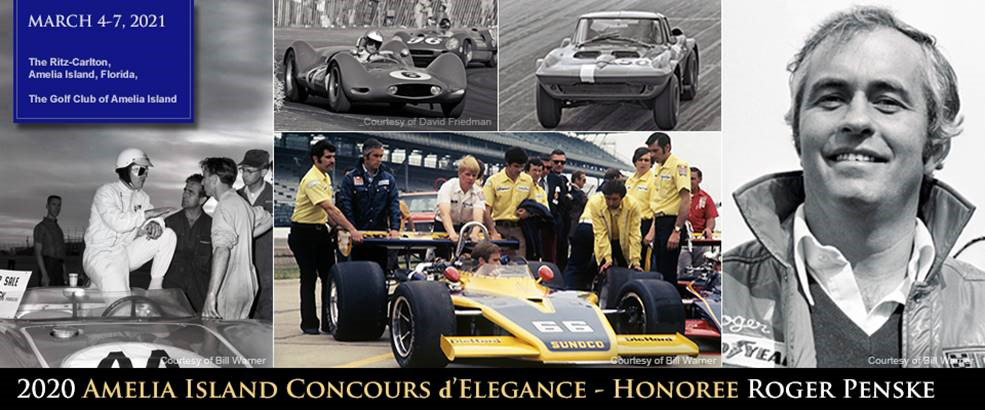

Don Cox started his career as an engineer with Chevrolet’s Research and Development after graduating from General Motors Institute. He worked on many projects in Chevrolet R&D including Jim Hall’s Chaparral from 1965 to 1968. In March of 1969, Cox was assigned to work with Team Penske in the Trans Am program as an advisor while Penske was running two Camaros in Trans Am – the #6 piloted by Mark Donohue and the #9 by Ronnie Bucknum. In November 1969 when he joined Penske’s racing shop at Newtown Square, PA, he became the team’s first dedicated engineer. “I was chief engineer because I was the only engineer!” Cox grins. In that race shop, his responsibilities touched every part of Team Penske’s racing enterprise – the TransAm cars, Indy cars, World Endurance Racing Ferrari 512 and both Porsche 917-10 and 917-30 Can-Am Champions. Cox and Mark Donohue designed Penske Racing’s first custom-made race shop when the team moved from Newtown Square to Reading, Pennsylvania in 1973. In the words of Bill Warner, founder and chairman of The Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, Cox is “the man who saw it all.”

Cox reminisces about those days: “Looking back to 1969, I started with Roger when the shop was an old cinder block garage with 4,000 square feet and a crew of eight guys.” The Captain also reminisces about those early years: “One little shop at Reading, we were doing CanAm, we were doing TransAm, we were doing Indy, and I think we were doing IROC. All out of the same shop, think about that! All those disciplines out of one small shop in Reading, Pennsylvania. Again, why were we successful? All about the people, and to me, that’s the greatest thing we have – the colleagues and associates around us.” Including Don Cox.

1969 Camaro, 305cid ovh valve V-8, two four-barrel carbs, 440 bhp, 2,980 lb. dry, 4-speed transmission, Corvette brakes, Goodyear Blue Streak Racing tires. Caption source: Car Life Magazine, January 1970. Photo: Luis A. Martínez

The beautiful Sunoco Blue liveried Camaros, the #6 car and #9 car, were very successful. So why leave GM to go to Team Penske and switch efforts to American Motors? Cox explains: “Penske had been running Camaros for a couple of years so during 1969 I had worked for Chevy R&D with the Penske project. But the official position of GM at that time was “no racing.” Other than technical assistance, Roger could not get any financial support from GM. By November I began working full time for Roger on a new program – American Motors’ Javelin, to make it competitive.”

Although Penske was a Chevrolet dealer, his relationship with GM on the racing front had gone sour so he felt compelled to explore working with a different vehicle. Towards the end of 1969 Penske initiated talks with American Motors Corporation. The deal with AMC proved lucrative – two million dollars for the season employing the 1968-69 TransAm championship team.

Penske had seen Javelins only at a distance, so this was all new territory and full of risk, as he knew AMC had struggled with their Javelin entries while he, Donohue, and Revson had secured two championships. Penske decided to bring back Peter Revson to race the second Javelin with Donohue.

The Penske Racing stable included a plethora of Sunoco-clad Can-Am racers, with Mark Donohue, Peter Revson, and George Follmer among pilots. Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

There were some important carryovers from the Camaro program to the Javelin effort, and it paid quick returns. “In 1970, Penske carried the numbers six and nine from the Camaros to the Javelins,” explains Cox. “Up to that point, the Javelins were not competitive. Donohue drove the #6 Javelin and Peter Revson was assigned #9. In 1970, after winning the championship with Camaros in 1968 and 1969, our Team Penske Javelin team was only one point short of the championship in 1970, but we beat all the other Camaros. So our Penske #6 Javelin with Donohue was very successful in 1971, winning seven out of ten races and finishing second or third in the rest.”

When Cox arrived on the scene from Chevrolet Development he immediately started on a new suspension for the Javelin, which was bottoming out, running on bump stops virtually all of the time on track. Cox designed the entire rear end, which included the housing, axles, full-floating hubs, spool, linkage to locate the rear, and brakes. Cox pointed out to Penske the advantage of Girling disc brakes with Lincoln rotors.

Don Cox and 1971 Trans-Am champion AMC Javelin at 25th Annual Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance. Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

As for the engine, Penske needed to develop special AMC engine components as the 290 CID was down 100 horsepower to the competition. Team Penske looked to Traco in California for all the engines for the 1970 season. Regulation limited engine size to 305 CID. Traco managed to shrink a 360 to regulation by destroking, while still making over 400 horsepower comparable to Chevrolet. But then there developed a litany of blown engines on the track caused by oil starvation due to G-forces when braking. Team Penske devised a dual-pickup oil pump with the secondary pickup scavenging oil from the uphill side of the pan, where it was accumulating during hard braking. Then, Cox had to address the strain of the dual-pickup pump which was wearing out the drive gears on the cam, affecting the distributor running off of the same gears, which was throwing off timing as the cars got further into a race. Cox found a solution by drilling new oil passages to feed oil to the gears.

With the highly revised Javelin racer, Donohue won the first race at Lime Rock, then lost the next two to George Follmer driving a factory Mustang. Donohue went on to win the next six races in a row, clinching the TransAm championship in the 1971 season.

Don Cox (middle) explains his role spanning many years with The Captain at the sold-out, standing room only conference, “Team Penske – the Early Years”, in Amelia Island. Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

At this year’s Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, in a seminar entitled “Team Penske: The Early Years,” Roger Penske waxed reminiscent about Cox in the discussion panel: “The TransAm was exciting, and Don, you really don’t give yourself the credit because you worked at General Motors and we needed someone in engineering to come with us and really change it. I remember, we took on the Javelin project because they offered us a terrific deal financially and to take our drivers and take on another challenge. Cox walked in the shop and the first thing he said was: “We’re going to put these brakes on this car.” Think about this, all these factory teams, Mustangs and Dodges, and Don came in and fitted these brakes. Now I wasn’t sure whether they were going to work but they gave us a competitive advantage from the standpoint of having the brakes that nobody else had. So those were early wins. And I think he’s probably modest.”

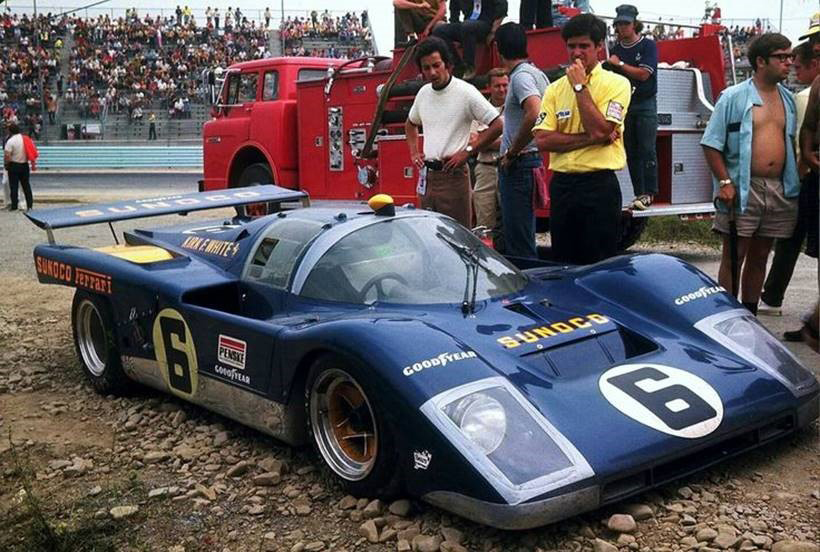

At the end of 1971, Penske was approached by Porsche to represent their marque in racing. What would prompt the Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG factory to seek the services of The Captain? Strangely enough – a Ferrari. There was this Ferrari 512S, chassis #1040 which had been lightly used in the CanAm Challenge. It was then purchased by a used Ferrari dealer in Philadelphia – Kirk F. White. In an effort to promote his fledgling car dealership, White approached Penske hoping Penske Racing would borrow the car and use Donohue to race it. Penske eventually agreed. Team Penske did substantial improvements to the 512 and, with sponsorship from White and Sunoco, Donohue drove it to appreciable success. “The reason that program got started [with the Porsche 917-10 and 917-30] was the success we achieved with the Ferrari 512M, a car that was owned by a local guy in Philadelphia [White]. As I recall, we did four long-distance races, and three out of four times we out-qualified Porsche with that car. Porsche decided they wanted to get into Can-Am racing in the U.S. and they were looking for an American team to actually run their cars in America. Because we had done so well with the 512M, compared to them, our team was one of the people they considered.”

Don Cox (yellow shirt) ponders his next move to keep Penske Racing’s Ferrari 512 in front of the Porsches. Photo: Gilles Robert, Pinterest.

At the Amelia seminar, with The Captain sitting in the front row, Cox laid out the real story: “We [Penske, Donohue and Cox] ended up going to Germany to talk to them [Porsche] about putting that deal together. I don’t know if Roger knows some of this. During the trip, Roger told Mark and me, “Now, you guys keep your mouth shut. I don’t want you to screw up this deal.” He said, “I’m going to go make this deal with Porsche.” So Mark and I just looked at each other. And when we get there, they have all these test cars to drive, and they have all this stuff to show us, and it was really an informative session with their engineers. At one point I got Helmut Flegl off to one side; he was their engineer who was going to be the head of this project that Porsche had assigned him. So I asked him, “What kind of wing are you going to have on this thing, on this new Porsche?” He looked at me and he said, “Porsche thinks wings are for airplanes.” And…. end of conversation, because I didn’t want to screw up this deal.” Penske and the audience laughed in understanding.

Donohue, Penske, Don Cox and Helmut Flegl at Weissach with normally aspirated test of 917/10 on that first trip to Germany. A much bigger wing was developed by Donohue and Penske. Photo: Porsche, Caption: Dean’s Garage

Cox continued explaining the saga: “Roger apparently made a deal so he said to me and Mark, “Okay, I think we got a deal.” So we got on a plane, Mark and I, to fly back to New York, and Roger went off somewhere else. All the way home, on the plane, we are talking and I said to Mark, “You know, I didn’t get a very good reception on that ‘what kind of wing are you going to have?’ thing. Now don’t forget the vacuum cleaner car [Chaparral 2J] was in existence in 1970. Anyway, I was thinking maybe they don’t want to do wings, maybe they got some other idea. Long story short, we didn’t even leave the airport in New York, we went back to Lufthansa and went back to Germany. We called Flegl and said, we have to have a meeting. So we had a meeting!” With a grin and a wink, Cox reveals – “Roger didn’t know this. We had a meeting with Flegl and he was a very, very bright guy, but he was new to motor racing, so we sat down and we explained everything about why have a wing, what it does, and it doesn’t matter that it has a little bit of drag, that you can sacrifice a little speed on the straightaway if you can gain significantly in the corners. And so you can see him coming right up to speed really quickly, and he said, “Okay, I will talk to the higher-ups.” About a week later we got a response on a Telex machine and it said ‘WE WILL HAVE WINGS.’ It all ended well, but it’s funny how it started.”

The Penske program for 917s was enormously successful. Starting with the L&M Cigarette liveried Porsche 917-10, Porsche earned their first CanAm Challenge Cup in 1972 with Donohue and George Follmer. Powered by the 5-liter air-cooled flat-12, the 917/10 was rated at 850 horsepower. That was a lot to handle even for the experienced Mark Donohue, who after an accident could not finish the season for the 1972 CanAm title. The white wedge became one of the most recognizable racecars in history.

Porsche 917-10 K Serial 003, driven by Can-Am Champion George Follmer, dominated the ’72 Can-Am series taking 1st at 5 of 9 races Photo: Anthony J. Bristol

Then came “the beast.” Considered by some the most powerful racing car ever to set tire to pavement, the 1973 Porsche 917-30 towered above all. This was a reliable rocket with a turbocharged air-cooled flat-12 engine of prodigious capacity. Its power ranged between 1100 and 1580 horsepower which Donohue could adjust from the cockpit. Weighing a scant 1,800 pounds dry, this CanAm contender, in its world-renowned blue and gold Sunoco livery, could sprint from zero to 200 miles per hour in 10.9 seconds. Top speed is estimated at more than 260 miles per hour, but who would dare test the limits?

Mark Donohue’s Porsche 917-30, at Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance 2020. Donohue turned fastest closed-circuit lap in world history at Talladega Superspeedway, AL, average speed of 221.120 mph. on August 9, 1975. Photo: Luis A. Martínez

Cox’s first experience with Indy racing was in 1970 with Penske’s Lola T150, the #66 car. It finished in second place. Cox explains his involvement: “For 1971, Penske switched to McLaren. We wanted to be very involved in the design so we contracted to build the cars in England, designed by McLaren with Team Penske input. In 1971, Donohue won the Pocono 500 with that car. In 1972, I was the engineer with Donohue in the #66 car, the McLaren M16B, and on May 27 we won Roger’s first of an incredible string of Indy races.”

The Captain adds his touch to the Indy stories, “The air jacks, think about that. We brought air jacks to racing. Going to Indy and these guys with these hammers, and trying to get the wheels off, and these jacks, and it was a joke. Wasn’t it? We were a little too sophisticated! They called us the college boys, remember? With the crew hair cuts and the polished wheels and the yellow floors. That’s what our reputation was at Indy. Well, 18 races later I think some of those guys got their garages better.”

Roger Penske (kneeling) and the crew of Mark Donohue’s Sunoco McLaren in 1971. Don Cox is standing 4th from left. Photo: Indianapolis Motor Speedway photo.

The Captain has been building his reputation for decades, and it’s a lot more than crew cuts, yellow floors, and polished wheels. Here’s a point of view from an uninvolved racing fan named Bob Collins. Bob was attending college in Adrian, Michigan. One weekend in the spring of 1977 he was bored in his dorm room, so he went to Michigan International Speedway to watch race cars test and tune. Bob parked his 1975 Olds Cutlass at the steel gate of a service road and sat on the hood of his car to watch the action. A well-appointed late-model sedan approached the gate and the driver, seeing Bob, looked discomfited. The gentleman then asked Bob what he was doing there, pointing out that this was private property. Bob responded, “Well, I was in my dorm room, really bored, everyone is gone, so I came over here to see the cars. I love racing cars. I’m from upstate New York and I’ve been to races at Watkins Glen.” A brief conversation ensued, and unexpectedly the gentleman went and unlocked the gate and motioned to Bob that he could drive his Cutlass for one lap around the 2-mile D-shaped track. That gentleman could offer such a gesture, unthinkable today, because he owned the track – Mr. Roger Penske.

Bottom center color photo of 1973 Indianapolis 500, #66 car Penske Eagle/Offenhauser with Mark Donohue. Penske is second from left, Don Cox is 4th from left with jacket over his left arm. Photo: Bill Warner Archives

Cox maintained a full time working relationship with Penske for seven years. But it didn’t end there. “I left the race shop in ’76 after Mark Donohue died in Formula One practice at the Österreichring in 1975.” Cox relates, “But I kept working on projects and races with Roger until 1989, a total of 20 years. During my 20 year involvement with Penske Racing, I saw Penske accumulate seven Indy 500 wins.” Penske Racing went on to win an astounding total of 18 Indy 500s.

Today, still living in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Cox remarks on the many years with Penske: “Thinking back as far as my work on the Camaros, or the Javelin, or in Germany with Helmut Flegl and the 917, it all ended well – but it’s funny how it all started.”