Organized races through the village of Watkins Glen and surrounding roads were started by Cameron Argetsinger in 1948, marking the beginning of post-war sports car racing in this country. Crowds grew steadily in the years that followed. But it was the 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix weekend, during the running of the main Grand Prix race, when a tragic accident occurred at the beginning of the second lap that changed everything.

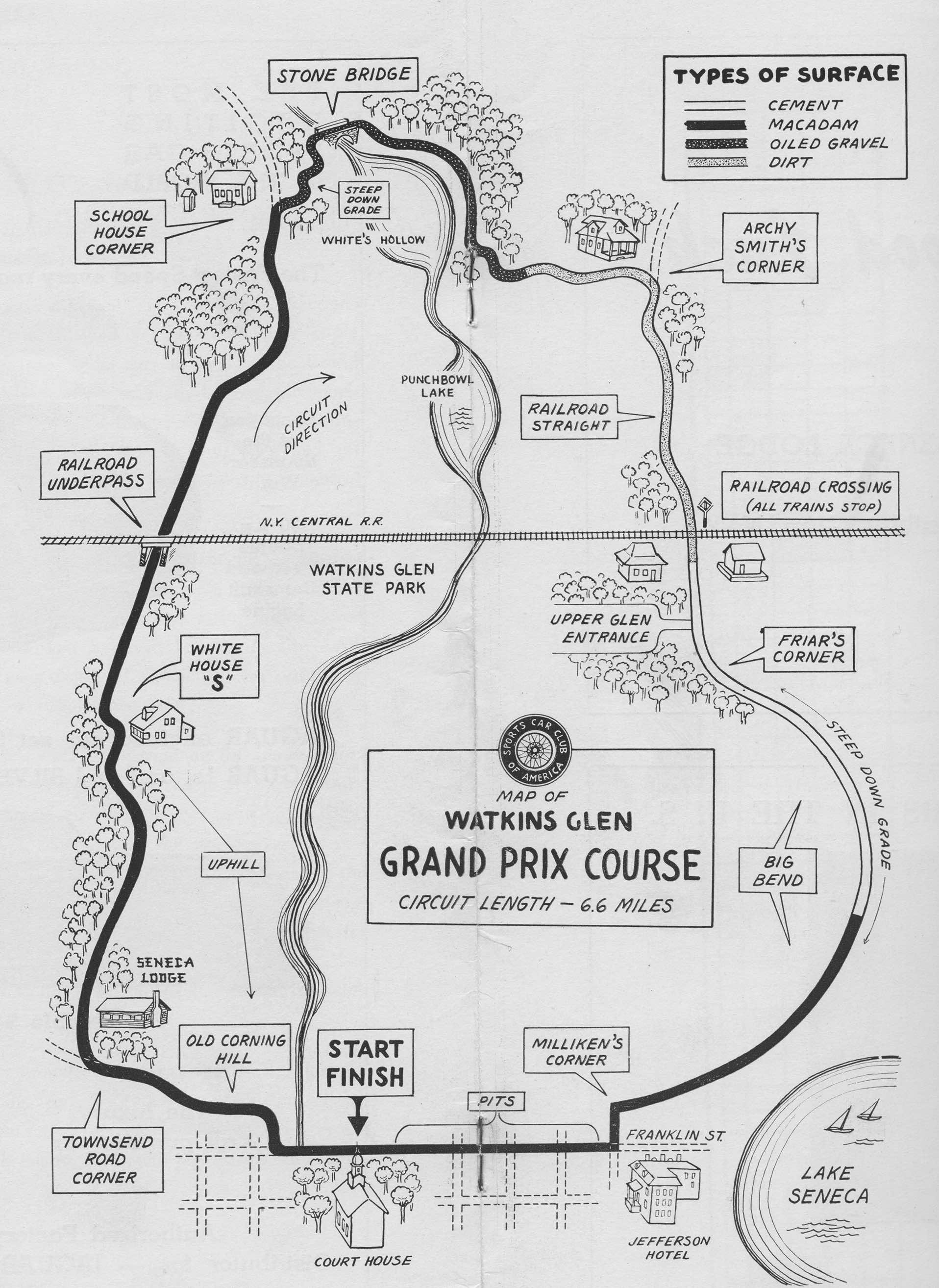

The original 6.6 mile Watkins Glen circuit utilized the main road through town, Franklin Street, as the front straight. The rest of the layout wound its way through the hills above town. Source: International Motor Racing Research Center

Fred Wacker, driving a Cadillac-Allard, attempted to pass second place John Fitch at the wheel of a Cunningham on the approach to the first turn, directly across from the main entrance of Watkins Glen State Park. Wacker brushed the crowd, injuring 12 spectators and killing a seven-year-old boy. This area of the track was designated as a no passing zone and a no spectator zone. Throughout the day police repeatedly chased spectators out of the location, but with a large crowd on hand that year it was impossible for them to keep full control of the excited swarms of spectators. After the accident, the race was stopped, never to be finished.

Because of the accident, road racing at Watkins Glen was at a crossroads in the late fall of 1952 and the early months of 1953. A short time after the September race, a public meeting was held to determine if the community would hold more races on the existing circuit or find a new circuit within Schuyler County. The general feeling was that a new, safer course should be found.

In its January 1953 session, the New York State Legislature considered two proposed laws to ban racing on public roads. One bill was passed in the Senate but never made it out of committee in the Assembly. Thus, there was never a law enacted to ban racing on public roads in New York State. What the State actually did was withhold issuing of permits for racing on state roads – dooming the use of the original 6.6-mile circuit at Watkins Glen, which was made up of more than 85% state roads. In addition, Lloyds of London, the insurer, refused coverage of the race if it ran through downtown Watkins Glen.

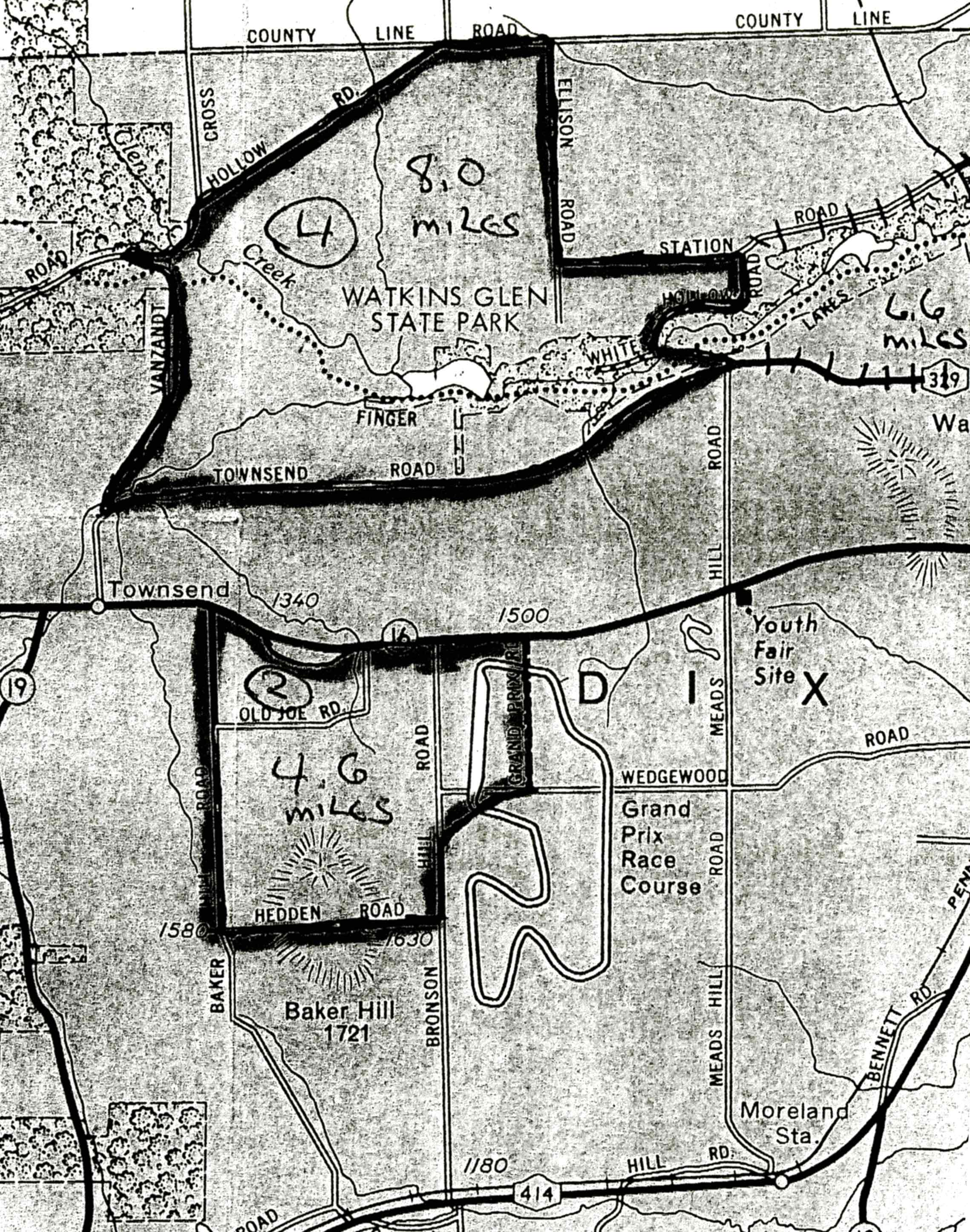

The Race Committee, empowered to make the selection of a new circuit, consisted of representatives of the community: Chamber of Commerce President Don Brubaker; Grand Prix founder Cameron Argetsinger; attorney Henry Valent; proprietor of Smalley’s Garage Lester Smalley; Watkins Glen Mayor Allen D. Erway; Schuyler County Highway Superintendent Ernest Porter; 1952 Grand Prix Chairman George Shannon; attorney Liston Coon; long-time member of the Chamber of Commerce Leon Grosjean; trainmaster for the New York Central Railroad (“the man who stopped the trains”) Frank Chase; and reporter for the Elmira Star-Gazette Arthur H. Richards, Jr. They considered five potential sites for the circuit: a 7.2 mile layout in the Town of Orange; two in the Town of Dix – one 8.0 miles and the other 4.6 miles; and, two circuits on east side of Seneca Lake – a 4.8 miles layout in the Town of Hector and a 6.7 miles layout in the Town of Montour (which overlapped in part the Hector circuit). Both the Hector and Montour layouts ran under the Lehigh Valley Railroad underpass at the Dolphsburg Road corner before making a right turn.

Most of the roads proposed for use as a replacement circuit were made up of county and town roads which were narrow and had little hard-top surface. They were largely gravel surfaces and the circuit selected would require widening and paving.

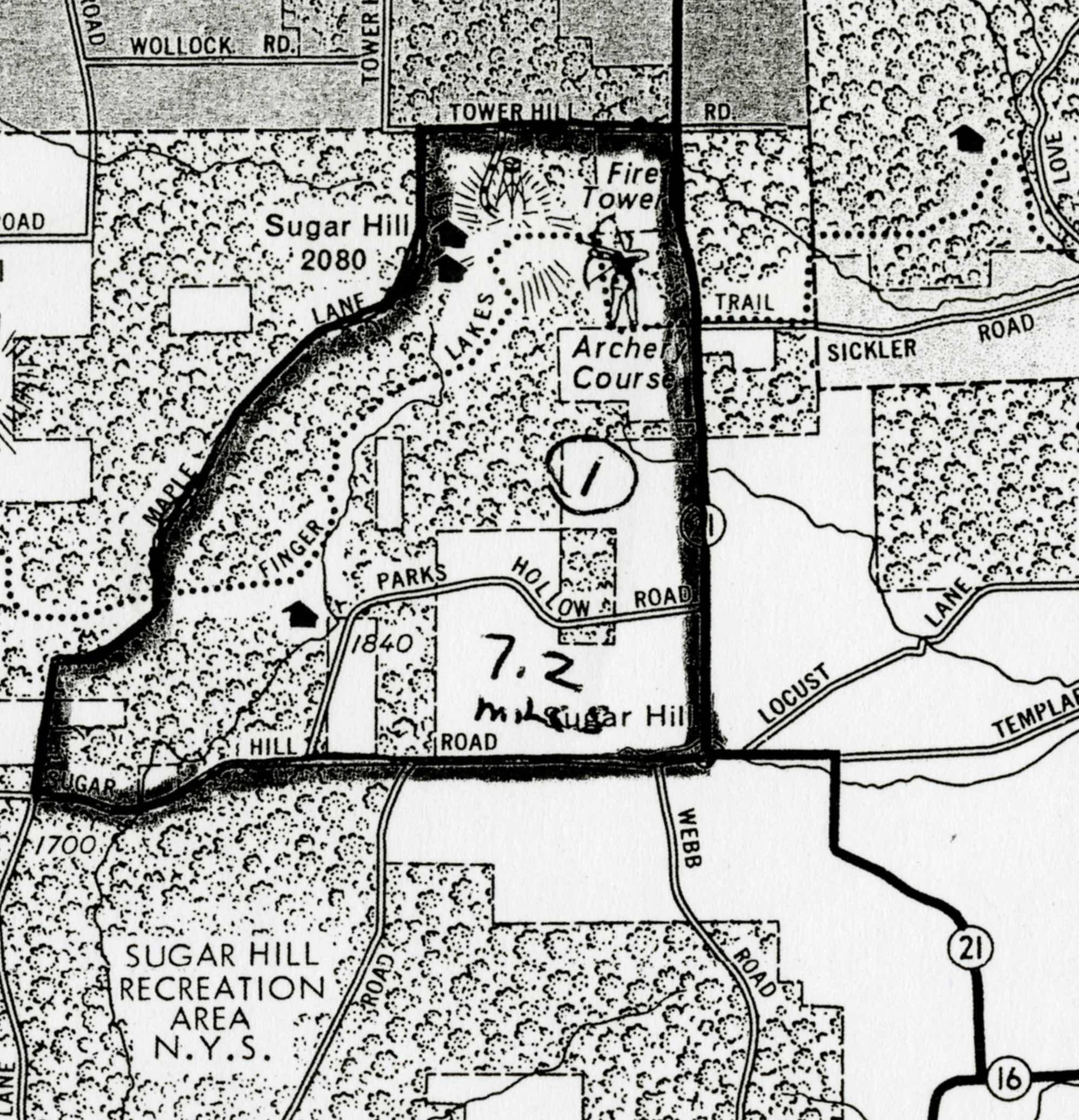

The 7.2 mile “Brigham Young” circuit layout was one of two race course sites considered by the Watkins Glen Race Committee following the disastrous 1952 Grand Prix through the streets of the town. Source: International Motor Racing Research Center

The Committee settled on two possible race course sites. One was a 7.2-mile course in the Town of Orange (called the Brigham Young Circuit) which would have run through the small hamlet of Sugar Hill. The second was a 4.6-mile course (called the Jane Delano Circuit) in the Town of Dix near the hamlet of Townsend.

Before the work was to start, the Committee asked James Lamb, Contest Board Secretary for the American Automobile Association (AAA), which then sanctioned sports car racing in the U.S., to tour the circuits and offer an assessment. He reported favorably on the circuits but was concerned that the road work could not be completed in time for the September 18-19, 1953 race date.

The 4.6 mile “Jane Delano” circuit layout through the town of Dix (bottom) became the home of the Watkins Glen races from 1953-1955 until the current track (illustrated to the right of the Jane Delano layout) was built on the hill above town. Source: International Motor Racing Research Center

The Town of Orange circuit ran through a section of the New York State Forest. The State Department of Conservation was uncooperative, fearing that spectators would cut down small trees for use in campfires during the race weekend which would lead to forest fires. For this reason, the proposed “Brigham Young” circuit was ruled out and the Town of Dix “Jane Delano” circuit was selected as the Watkins Glen Grand Prix venue.

After meeting with the Town of Dix Board, the race organizers were given permission to make use of town-maintained roads. A short time later, SCCA representatives, unable to make a complete tour of the proposed 4.6-mile circuit because of road conditions, decided they would not sanction the 1953 Grand Prix.

On July 15, the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation was formally organized and chartered. The organization originally consisted of seven directors appointed by the Watkins Glen Chamber of Commerce. The Grand Prix Corporation soon issued bonds in the form of “Six-percent Certificates of Indebtedness” in the sums of $100, $500 and $1,000. The Corporation leased all the grounds surrounding new circuit, entitling them to the exclusive and complete jurisdiction of the leased properties. In exchange, landowners received one-third of the profits from the event, with the remaining thirds shared equally by the Community Chest and the Grand Prix Corporation.

Bill Milliken and George Weaver were consulted regarding road work and related engineering considerations. Work started on August 2 with the construction firm of Martin & Son of Burdett, New York as the general contractor. All around the course trees, hedges and brush were removed and utility poles and fences were relocated. The road was widened to 28 feet and the shoulders extended to four feet on each side of the road. Extensive grading, ditching and culvert work was also required. Remarkably, on August 19, one month before the race, work was finished and the course was half completed. The remaining half, laying the asphalt, was undertaken by the Watkins Glen firms of Harry Suits and Franzese Brothers. Completed on September 9, the track was ready for the race on time.

It was decided that no spectators would be permitted inside the track or within 30 feet of the track. Spectators were not allowed to drive on the actual course to reach the designated parking areas at any time during the race weekend. RCA race safety systems and public address systems were installed around the circuit.

General admission for the races was $1.25, grandstand seats ranged from $3.00 to $5.00, and parking was $1.00 per car. For the first time in the Glen’s history, Friday prior to race weekend was used for official practice.

On Saturday morning, the first race of the day was the Seneca Cup, an 11 lap (50.6-mile) event, with 19 starters. The race was won by Dr. M.R.J. Wyllie driving a Jaguar XK120M, with Wyllie moving out on the shoulder to pass Phil Cade’s Grand Prix Maserati R1 in the final turn of the last lap, winning by less than 100 yards. He averaged 72.1 mph.

Later the same day, twenty-nine cars took the green flag in the Queen Catharine Cup, a 22 laps or 101.2 miles race. George Moffet claimed the victory, driving an OSCA with an average speed of 73.7 mph.

Looking back at the last turn before Start-Finish line at the1953 Watkins Glen Grand Prix, the #90 Jaguar XK-120 of Gled Derujinski leads the Siata of Otto Linton (#58) and the Jaguar XJ-120 of George J. Constantine (#49). Source: William Green Motor Racing Library/International Motor Racing Research Center

The last race of the day was the 6th Annual Watkins Glen Grand Prix, a 22 laps (101.2-mile) event with 27 cars starting. The Grand Prix featured a race-long duel between Walt Hansgen driving the Hansgen Jaguar Special and George Harris in a Cadillac-Allard. The lead changed hands four times on the last lap, with Hansgen winning by a scant 1.1 seconds at an average speed of 76.1 mph.

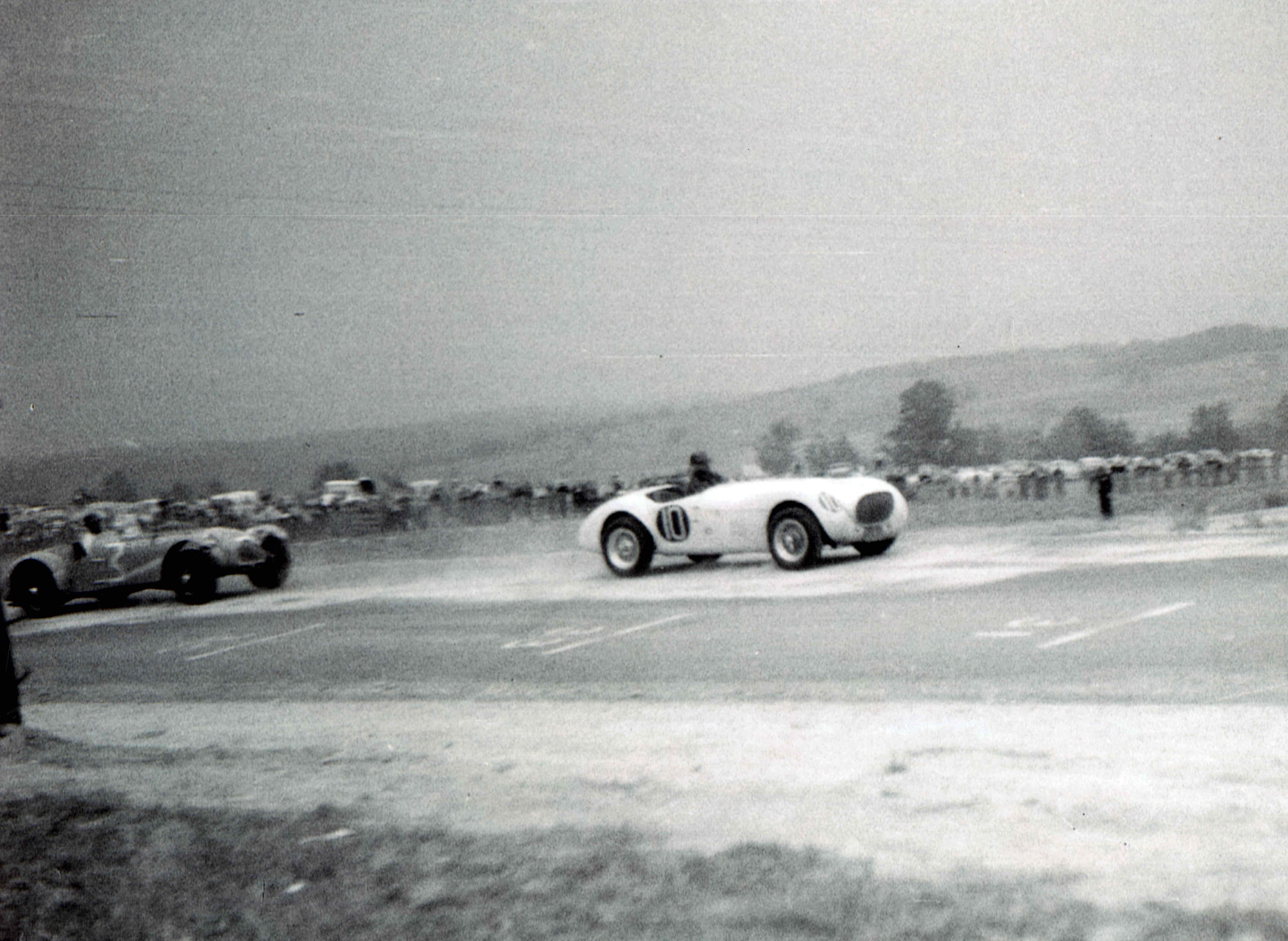

The 1953 Watkins Glen Grand Prix, at the last turn of the last lap. The Hansgen Jaguar Special of Walt Hansgen (#10) leads the Cadillac-Allard of George Harris (#3) across the line for the win. Source: William Green Motor Racing Library/International Motor Racing Research Center

The race on the new circuit was judged a huge success in the local press, with crowd estimates ranging from 20,000 to 60,000. The next two years’ races were sanctioned SCCA national events and run on the same circuit. Today, parts of the 1953-1955 circuit run through the current racecourse at Watkins Glen International, built in 1956 and substantially rebuilt in 1971.