“At Mosport, we had a little rev problem, and were over-winged, but we hung in there for seventh. Here we’ve learned a little more. We were getting it all to work for us until that pump died on the start, and we got disqualified. But that’s racing, you know… Hopefully, we can make it a better car yet, and really, it’s so good to be here again in Formula 1, it really is. It’s the thoroughbred of racing, you know it’s the top…” Mario Andretti, Watkins Glen, October 1974.

Mario Andretti wheels the Vel’s Parnelli Jones Formula One car at Watkins Glen in 1974. Photo: International Motor Racing Research Center.

Back in 1974 at Watkins Glen for the United States Grand Prix, I got the chance to sit down with Mario Andretti – in the Vel’s Parnelli Jones team’s section of the Glen circuit’s Technical Centre – and hear from him about his life and career that far. Mario came across as a hyper-competitive sportsman of great – and continuing – achievement and experience and, as a man, he was friendly and engaging and one who conducted himself in a gently distinguished (and highly impressive) manner.

To me, as a hopeless race reporter – by temperament far too shy and reserved ever to ask questions of anyone to whom I had not yet been introduced – the time Mario gave me that day seemed incredible. How had I got to him? Well, both Vel’s Parnelli designer Maurice Phillippe and team manager Andrew Ferguson were fellow Brits, ex-Team Lotus in England.

I knew both well from Lotus days, and it was Andrew who overcame my natural reticence – called me over and said “Hey Mario – here’s someone you ought to meet – he’s OK”. So, there at the Glen that day, I taped a long conversation with America’s finest Italian-born racing driver. And here’s the feature story based upon it that I put together over the next few days. – Doug Nye

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

It took just under four minutes for Mario Andretti to make himself an ace. To be precise he took 3 minutes 46.63 seconds, pelting his Dean Van Lines Special round Indianapolis to steal pole position and set new four-lap and one-lap qualifying speed records, first time out on the Speedway.

Mario Andretti poses in his Dean Van Lines Brawner-Hawk after qualifying fourth for his first Indianapolis 500 in 1965. He would finish in third and win rookie of the year honors.

That was nine years ago, in 1965, and until then Mario had been just another successful young kid from the dirt tracks, full of apparent potential in his first few USAC Championship races, but yet to deliver the goods. As he pulled his bulbous white Ford-powered car into the Indy pit lane the crowd roared themselves hoarse at his performance. But the wiry 25-year-old Italian immigrant was already looking over his shoulder. Jimmy Clark followed him out onto the Speedway, and he turned in four consecutive laps over 160 mph to steal Andretti’s pole position and his records. At the end of the day, A. J. Foyt had taken top qualifying honours, and Mario was fourth quickest, bumped back to the inside of the second row by Dan Gurney. In the race, his first Indy 500, the tough little man from Nazareth, Pa, then drove like a veteran, despite an intermittent fuel system fault afflicting his car. He lay with the leaders from the start, hounding Rufus Parnelli Jones all the way until the race drew towards its dramatic finish.

Clark rushed home to win for Lotus and Ford, nearly two minutes ahead of Jones’ year-old Lotus which was in deep trouble. It was running low on fuel, and with Andretti just 20-seconds astern, Parnell dared not stop to top-up. On the last lap, Jones zig-zagged his faltering car across the line, just managing to wash the last remaining dregs of fuel into the pick-up pipes, to hold off Andretti by just six seconds.

So the mercurial Rookie was third in his Indianapolis debut, winning a well-deserved Stark & Wetzel Rookie of the Year award, and also being voted Driver of the Year by the Hoosier Auto Racing Fans. They knew what they were talking about. He ended the season by winning the USAC National Championship, and he repeated this feat the following year.

Since then Mario Andretti has become Internationally-acknowledged as one of the most versatile and capable race drivers of all time. He has won on dirt and paved ovals; he has won stock car races on the high-banked super-speedways of the American deep south; he has won on road circuits in USAC Championship cars, long-distance sports car classics, in Formula 5000 and in Formula 1.

In 1969, he won the prestigious Indy 500, and in 1971 he won the South African Grand Prix. He is back in Formula 1, driving for the prime target in that now far-off Indianapolis 500 —for Parnelli Jones. His brand-new Maurice Phillippe-designed Vel’s Parnelli VPJ4 made its debut in ‘Super-Wop’s’ hands in the Canadian GP, and he perched it briefly on pole position for the United States GP at the Glen. Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones now have their team poised to tackle a full World Championship season next year, and after their spoiled Watkins Glen performance, they obviously mean business.

I found Andretti in the Kendall Tech Centre at the Glen after the Grand Prix’s first practice sessions had ended. He had set fastest time. The car was on pole overnight, and there was no mistaking the heart-warming rosy glow around the Vel’s Parnelli work bay.

The Tech Centre at the Glen is a great gloomy barn of a place, fenced off into a series of bays with a spectator-packed aisle down the centre. They pay a dollar a time to pack into the place for a close-up look at the great cars and great names of the day. The place is reminiscent of any English country-town’s covered cattle market, but here the all-pervasive pong is one of synthetic rubber, oil and cleaning fluid, instead of you know what.

Mario is a deceptive character, small in stature, broad-shouldered and powerfully built. He’s a big man in attainment, and he wears competitive nature like a badge. It’s as unmistakable as the Ferrari escutcheon which he still wears proudly on his Firestone jacket.

Motor racing was just starting its final pre-war season, confined to Italian territory, when Mario and Aldo Andretti were born as twins on February 28, 1940. Father was a farmer, and the family had seven farms in lstria, around Trieste where the Adriatic bites the division between Italy and Yugoslavia. At the end of the war, the Andrettis’ land was swallowed by a political settlement with Yugoslavia. The family wanted to stay Italian as the border was adjusted, so they abandoned their heritage to the new communist state and joined thousands of refugees moving westward.

Andretti is matter-of-fact about what must have been at first a confusing and later a bitter experience for a young kid. “We left in 1948, and lived in a refugee camp at Lucca—it’s near Pisa—for the next seven years. Yeah, it was tough. There were twen’y-seven families all living in one big room, about the size of this…”, he said, waving his hand at the Tech Centre’s walls.

“It was in Lucca that Aldo and I started around the local garage. The guy who ran it had ambitions for his son in racing, bought a Stanguellini and kind of pushed him into it. We were only around t’irteen or fifteen, and we used to help around and just soaked up the racing atmosphere. I remember there was one really great day, we went to Modena to pick up a ’53 Ferrari for the Mille Miglia, that was a great thing… “.

“We had an uncle, he was a priest, called Ghersa Quirino, and I guess he sympathised with our ent’usiasm. He bought us a 175cc MV motorcycle, without our parents knowing, and we raised hell with that around Lucca— all these little tight streets and alleys you know, it was the ideal training ground. We really loved motorcycle road racing…” (expansive gesture with the hands) “…any kind of road racing, and then we had great aspirations to get properly involved sometime.”

The family had relatives already living in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, and they acted as sponsors to help Mario’s folks emigrate there in the late ’fifties. By that time Mario and Aldo had driven their first motor races in an 85-horsepower Stanguellini-Fiat Formula Junior car, and they came to America hoping that at least one thing would not have changed much in their new life.

They were in luck. Three days after arriving in Nazareth they heard the rumble of modified stock cars racing on a nearby track: “We got over there quick as we could. We looked at the people driving and at the cars they drove and thought ‘hey, this looks easy’, and that was that….”.

The twins had another uncle, Louis Messenlehner (“…he was German, you know, on my mother’s side…”) who helped them to learn the language and, clandestinely so their parents would not suspect, to put together a modified stock car of their own.

“It was an old ’48 Hudson. Marshall Teague had been king in those cars until he was killed the year before we got started, but his folks and mechanics gave us all their know-how on spring-rates and shockers; it was pretty much unknown sophisticated stuff at that time.

“You had to be 21 before you could race in America, and we were only 17, but Les Young who was a newspaper editor on the ‘Nazareth Key’ helped camouflage our date of birth and we got in there. Aldo won the first race from starting at the back. We won our first three events, you know, we were quite successful all through our stock car days…”.

They had some low notes, as when in their first season (1958) Aldo got the Hudson out of shape and crashed heavily during a race at Hatfield, Pa. He suffered a concussion, and Mario had a hard time convincing Papa that Aldo had accidentally fallen off the top of a truck while watching the racing.

Unfortunately, Aldo was never again to be quite such an accomplished natural driver as his brother, and after trying hard in midget and sprint cars, he sustained severe head injuries through crashing a sprinter in 1969 and hasn’t raced since. Today he lives in Indianapolis, runs a couple of Andretti Firestone tyres stores, and accompanies his brother to most of his races.

In 1958, ’59 and ’60 Mario won over 20 modified stock car events, and in 1961 moved into the single-seater scene on the URC Sprint Car circuit. He was old enough to race legally but had some problems making the transition. “I just didn’t know which way that car was goin’ to go”. He ran with URC until the middle of 1962, when he began driving midgets in ARDC.

It was a rough and tumble schoolroom, of a type simply non-existent in Europe, which provided a staggering amount of experience: “I did 107 races in 1963, you know…

“In Midgets, you can regularly do 80 races on up each year. Sometimes we’d do t’ree races a week, and on Labour Day ’63 I won three races in two meetin’s ! Today just physically you can’t do that, but those Midgets really were the most constructive racing I’ve ever done. I tell you, you never run closer than in Midgets. You’d have 45-50 cars to qualify for only 18 places in the Final, and winning in Midgets can give tremendous satisfaction. I really felt I was accomplishin’ somethin’.”

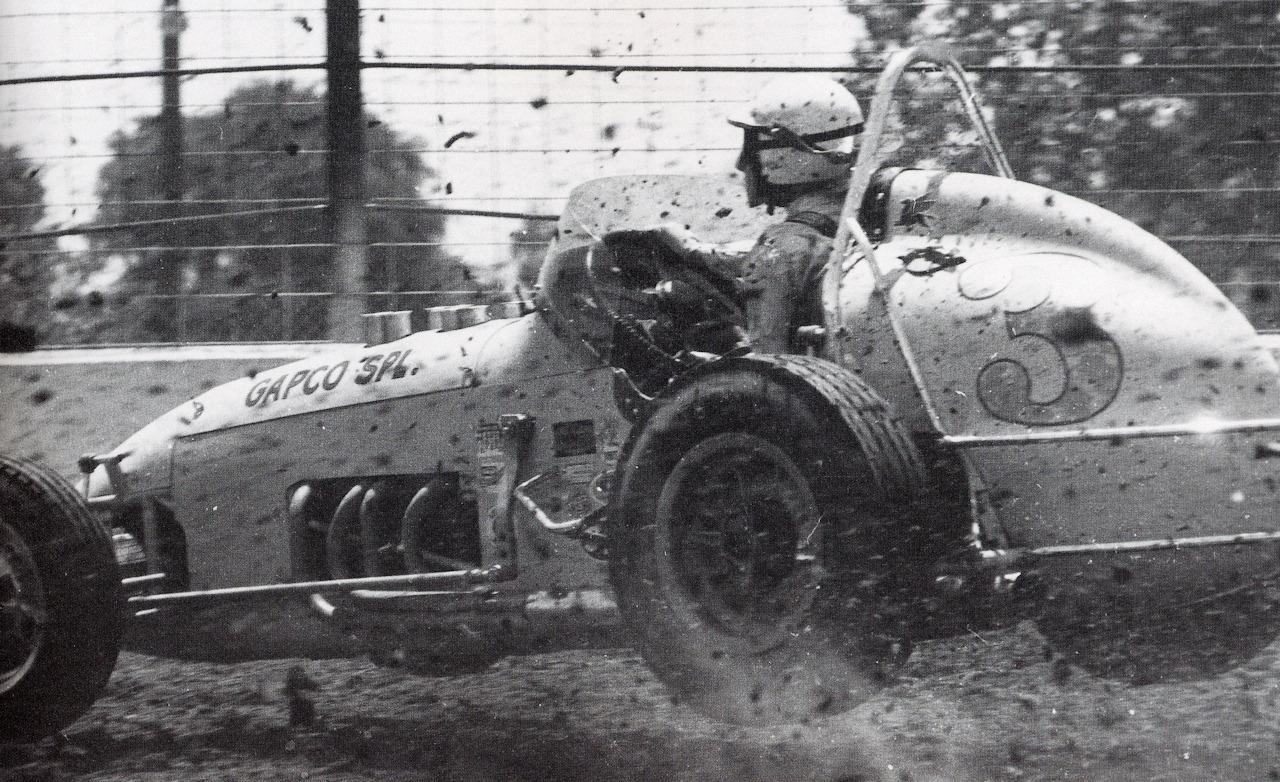

Andretti continued to race Sprint cars on dirt even as his international racing career took off, as pictured here at Terre Haute in 1965.

He drove an Offy-powered Midget for Bill and Ed Mataka that season, and early in 1964, he joined the United States Auto Club to get into Championship racing, to tackle the big-time. “That had been my goal since I started in sprints, you know. When you’re just starting you gotta set your aims high; unreasonably high at the time, and you just gotta get out and get after them. You tell yourself to do it…”, a shake of the head, “Shit, you just tell yourself these things, you know….”

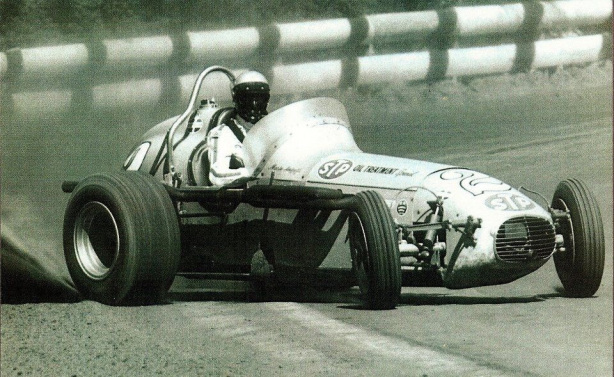

Mario hangs in out in the dirt at Sacramento in 1966.

Mario’s first Championship race was at Trenton, NJ, in March ’64, and it wasn’t too happy a debut. “I was like a fish out of water. I mean I spun three times. I tell you, I just felt incapable! Those paved tracks were hard to drive at first. I was used to hanging my Sprint car out and tossing it around. In comparison those roadsters were a son of a bitch, you had to drive ’em like t’readin’ a needle…”

The story goes that Mario visited Indy that year; just a 24-year-old dirt track driver soaking up the Speedway’s carefully manufactured mystique for the first time. But he wasn’t overawed by the place. He was wandering around Gasoline Alley looking for a drive. He looked up Al Dean’s veteran crew chief Clint Brawner, who had just lost his driver when Chuck Hulse was seriously injured in a sprint crash earlier that month. Rufus Grey, who owned the sprint car Andretti was driving at the time, introduced his young protégé and tried to talk him into Brawner’s Dean Van Lines roadster. When he mentioned that Mario raced sprint cars, Brawner’s sun-sensitive neck apparently reddened, he bawled “Goddammit, sprint’s a dirty word in this garage”, and tossed the hopeful applicants out of the door!

But Brawner had heard of Andretti’s prowess from other sources, and a month later he watched Mario drive at Terre Haute and offered him the Dean drive, mere or less as a trial until Hulse recovered. The compact little Italian jumped at the chance; “In major league racing, I figured there were only a few outfits worth driving for, that were going to produce a winner. I considered Dean one of these, so I t’ought maybe I’m gettin’ into somethin’ good.”

He drove the Dean Van Lines Special in the last eight Championship races of the ’64 season, was third in the Milwaukee ‘200’ and notched sufficient points for 11th in the Championship standings. He drove in 20 sprint races, was third in the standings and highlighted with victory in the Joe James-Pat O’Connor Memorial 100-lapper at Salem.

— Continued in Part Two