The famed Daytona International Speedway was built in the late 1950s as a state of the art facility – the crown jewel of the NASCAR stock car season. But the track had been designed from the beginning to include a road course layout and “Big Bill” France, Sr. aspirations beyond just stock cars. In June of 1961, he attended the 24 Hours of LeMans and was stunned by the sight of more than 250,000 spectators. Upon returning home, he hatched an idea to bring global credibility and prestige to his new Daytona facility. Partnering with the SCCA, he started the Daytona Continental sports car race in 1962. Originally run as a three-hour event that year and the next, it was expanded to 2,000 kilometers in 1964 and 1965. By 1966 it had expanded yet again to a full 24-hour length to match the Le Mans 24 hours race. The first 24 Hours of Daytona was won by Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby in a Shelby Ford GT40 MK II. The Daytona 24 then became a fixture on the World SportsCar Championship schedule. Ferrari had their famous 1-2-3 finish in 1967, followed by Porsche with their own 1-2-3 finish in 1968. The 1970 and 1971 races were highlighted by great battles between the Porsche 917 and the Ferrari 512, both races being won by the Gulf Porsche 917.

The driver’s meeting just before the1972 Daytona race, which was shortened to six hours by the FIA over concerns that none of the 3.0-liter prototypes would survive a full 24 hours. From the left: Ronnie Peterson, Mario Andretti, Jacky Ickx, Clay Regazzoni, and Peter Revson (in the blue jacket). Photo: Martin Raffauf

For 1972 the FIA had changed the rules dramatically. The Sports Car World Championship was now limited to 3.0-liter cars, effectively banning cars with 5.0-liter displacements. With some foresight, Ferrari had been working on and racing their 312P car during 1971, gaining experience for 1972. The Ferrari 312P was powered by a derivative of the then-current 12-cylinder Formula 1 engine. Alfa Romeo also had a 3.0-liter car, powered by a V8. Porsche, as a factory, withdrew from the series, as they only had the aging 908, with a 3.0-liter flat 8- cylinder engine. The FIA also raised the minimum weight for the class which handicapped the lightweight 908, as it was underpowered in comparison to the Ferrari and Alfa Romeo. Porsche racing was left in the hands of privateers. Due to reliability concerns, the FIA mandated 6-hour maximum races in 1972, except for Le Mans. Sebring fought this and kept their 12-hour race, however, Daytona agreed to the 6-hour limit. Daytona did schedule several support races over the 24- hour time period, to make it seem like it was 24 hours of racing. But the World Championship race would run on Sunday for six hours only.

The winning Ferrari 312PB of Jacky Ickx and Mario Andretti sits in the paddock before the race. Photo: Martin Raffauf

The Alfa Romeo T33 of Vic Elford and Helmut Marko in the garage area. It would finish third. Photo: Martin Raffauf

The Kremer Porsche 911S was one of many GT cars that filled out the field in 1972. The car was a DNF. Photo: Martin Raffauf.

Both Ferrari and Alfa Romeo entered three cars each. The Ferrari’s were the new 312PB (a further evolutionary development of the car run in 1971) and were driven by Mario Andretti/ Jacky Ickx; Ronnie Peterson/Tim Schenken; and Clay Regazzoni/Brian Redman. The main competition would come from the Alfa Romeo TT33/3’s of Peter Revson/ Rolf Stommelen; Vic Elford/ Helmut Marko; and Andrea de Adamich/ Nani Galli. There was also a quick Lola T280 entered by Jo Bonnier and co-driven by Reine Wisell. A full field of GT cars and a few older prototypes and 2.0-liter sports cars filled out the grid.

Reine Wisell in Jo Bonnier’s Lola 280-Ford ran well until an accident. Photo: Martin Raffauf

Mario Andretti qualified on the pole and took an immediate lead. However, in the early going the car lost a cylinder with no spark. There was some kind of wiring or electrical problem that could not be fixed quickly. They just carried on. Mario reckoned they lost 800-900 RPM, so just drove harder. Their team-mates, Regazzoni and Redman took the lead and were in front until a tire blew in the banking just in front of Reine Wisell who was running second in the Lola. Both cars were damaged in the incident and needed extended pit work to continue. The Alfa Romeo of Revson and Stommelen then took over the battle for the lead with the slowed Ferrari of Andretti/Ickx, leading several times until the Alfa engine failed about halfway thru the race.

Peter Revson in the Alfa Romeo on the East banking during the 1972 Daytona six-hour race. The pair of Revson/Stommelen would blow the engine halfway through the event. Photo: Martin Raffauf

The Andretti/Ickx car led the rest of the way, winning on just 11 cylinders over their teammates, Ronnie Peterson and Tim Schenken (who had a clutch problem the whole race). Vic Elford and Helmut Marko ended up third in their Alfa, four laps behind. The Regazzoni/ Redman Ferrari was fourth after earlier repairs from the tire failure cost them 15 laps. Of the 72 cars entered, 58 qualified but only 21 were classified finishers. So, it seemed apparent the FIA was correct with their reliability concerns.

In a foreshadowing of things to come, Peter Gregg and Hurley Haywood finished 7th overall and first in class with a 2.5-liter Porsche 911S. They would return with some success in subsequent years!

In 1973, the race returned to its normal 24-hour length and has remained as such ever since, with the exception of 1974 when the race was canceled in the middle of the fuel crisis. In 1975, IMSA took over the sanctioning of the event and it remained on the World Championship calendar until the early 1980s. At that point a large rule divergence between the FIA (Group C) and IMSA (GTP) caused the race to fall off the international calendar.

The Ferrari 333SP was a beautiful workhorse of the IMSA series in the mid-1990s. Chassis number 012 sits in the Mugello pit lane awaiting a track lapping event in 2018. Photo: Martin Raffauf

In the early 1990s, Gianpierro Moretti approached his friend, Piero Ferrari about Ferrari building a sports prototype. It was a hard sell, but Moretti, along with IMSA (International Motorsports Association) eventually convinced Ferrari to build a customer car for the new IMSA Exxon WSC (World Sports Car) rules which were to take effect in 1994. This would be the first prototype sports car Ferrari had built since the 1970s and the 312 series.

Gianpierro Moretti was the brain trust and owner of the MOMO performance gear company. He was instrumental in convincing Ferrari to build the 333SP for the IMSA World Sportscar Challenge (WSC) series. Photo: MOMO press kit, 1994

Conforming to the WSC rules, the Ferrari 333SP was designed as a flat bottomed, open cockpit prototype. Engines had to be production-based and could either be based on a 4.0-liter “racing” version, or 5.0- liter stock block motor. Ferrari made the decision to use a derivative of the F50 engine and de-tuned it. In effect, this was a derivative of the 3.5-liter Formula One motor being used by the Ferrari team at the time. It was a 65-degree V12 that produced about 680 horsepower in its ultimate configuration. In later years, as FIA rules changed the original IMSA specifications for use in Europe, restrictors came into vogue and the Ferrari engine was severely limited in power. Ferrari basically gave up on the formula (rightfully so in my opinion), as their view was that this engine was not designed for a restricted formula.

The Ferrari 333SP cockpit was pretty basic compared to today’s modern sports racing cars. Photo: Martin Raffauf

In the end, some 40 or so Ferrari 333SP chassis were constructed, all of them being built by Dallara. The early cars were assembled by Ferrari in Maranello, the later ones were assembled by Michelotto in Padua.

In all, the cars were very successful. They won quite a few IMSA races between 1994 and 2001, eventually taking both the 24 Hours of Daytona and 12 Hours of Sebring races in the hands of Moretti’s Doran Racing Team. Ferrari also won the constructor championship in IMSA and the European based ISRS (International Sports Racing Series) multiple times.

The Ferrari 333SP was a fearsome competitor in the hands of independent IMSA teams. Photo: Martin Raffauf

None of the cars were factory entries but were all run by privateers. Notable entrants in the USA were, of course, Moretti, Andy Evans, and Fredy Lienhard. Fredy was probably the only entrant to participate on both sides of the Atlantic, running one car in IMSA and another in the European ISRS series. Ferrari did support the IMSA series and their 333SP customers, as long-time Ferrari engine man, Renzo Setti, was the designated factory support for the teams after 1994.

Confusion reigned in sports car racing in the USA by the late 1990s. IMSA had changed hands multiple times by this point and eventually was sold to Don Panoz, the inventor of the nicotine patch and ultimate car guy. Panoz resurrected the IMSA name as the organizer behind the ALMS (American Le Mans Series). Sports car rules (now under control of the ACO and FIA) shifted to a restrictor- based formula. Ferrari refused to modify or design any new engines, as in their view, this is not what the 333SP was built for. Once restrictors appeared, the 4.0-liter V12 became severely disadvantaged compared to larger engines from Ford, BMW, and others. Restricted, the engines suffered a loss of power, torque, and fuel economy, and were basically uncompetitive for the last years of the cars race history.

Kevin Doran, the team principal of Fredy Lienhard’s team, even went so far as to install a Judd V10 engine in the 333SP chassis, creating what became known as the FUDD (Ferrari-Judd). Some success was experienced with this configuration in 2000 and 2001, although by then there were newer more competitive chassis from other makers. Ferrari had gone back once more to concentrate on Formula One during the age of Michael Schumacher, and all future customer race car programs would become GT road car based.

By the end of 2001, even stalwart Fredy Lienhard put the Ferrari 333SP-012 back into his Autobau collection and bought a new Dallara-Judd. The 333SP was now relegated to vintage racing. As is the case with most Ferrari race cars, they soon increased in value exponentially. Because of their increased value, not many were ever, or are now raced in vintage events, although a few appear at Ferrari’s annual Corsa Clienti World Final events. Moretti boasted to me once in the 1990s about how he had bought a car (Ferrari), raced it all year, then sold it for what he had bought it for, about $500,000. He deemed this as “good value.” His 1998 Daytona and Sebring race winning car reportedly sold recently for five million dollars!

Fredy Lienhard still owns Chassis 012, and from time to time, takes the car out to “track days” for his friends and business associates. I worked on his race teams for Kevin Doran for many years, so I was fortunate to be invited to one of these events in early 2018 at The Mugello Circuit in Italy (and again in 2019 at Mugello).

Weather permitting, I would get the opportunity to go for a ride as a second seat had been mounted in the car for passengers. Although I had worked on these cars for many years, changing engines, gearboxes, installing and removing suspension and brakes, I had never actually ridden in one. The only real race cars I had ridden in were a Porsche 935 in the late 1970s, and a BMW 235-i Cup car. Having had quite a bit of history with this Ferrari, it was with some anticipation that I looked forward to seeing what it was like to actually experience it at speed.

Mugello in March can be cold. In fact, the days we were in-house (at the circuit), there was snow on the hillsides around the circuit which sits in a valley. So, it was unclear if this was going to work or not. The 333SP has to be warmed up with a water heater, especially during cold temperatures, as there is a danger of the radiators splitting. The minimum recommended water temperature to start the car is 50C.

The Mugello circuit was cold and wet when we showed up in March 2018. Photo: Martin Raffauf

Despite the cold temperatures, we got the car warmed up and Didier Theys took a few laps to make sure all was in good order. I suited up and prepared to get in. The immediate sensation is that this is a tight fit. The second seat, if you want to call it that, is just some padding and some belts next to the driver. Getting in and buckling up, the sensation is that you are sitting on the pavement. Very different from a road car or race car based on a road car such as a Porsche 935. The Ferrari 333SP is a 680 HP go-kart!

Acceleration is massive, the car just leaps forward. The noise of the engine without earplugs is deafening. As you exit the Mugello pits, you are on a long straight, the longest on the course. You go over a rise, then descend slightly downhill to the first corner which is a long radius 180- degree right-hand corner. At the end of the Mugello straight in this car, the speed is in the neighborhood of 185 mph Braking here is very, very impressive in this car (with steel brakes, no less). The first impression of a non-driver is that there is no way the car will stop. However, it does of course (Didier later told me he was braking 50 meters early, only running at about 80% capacity). I am convinced the G force of braking would throw you out of the car if you were not strapped in tight.

Due to the “passenger” seat configuration, I found my head was sticking up into the airflow more than Didier. The force of the air tended to want to rip my helmet off. So, I had to hang on with one hand and hold the front of the helmet down with the other to see where we were going. All the while, I had to be careful with the spare hand, as right in front of me was the switch panel, with all the ignition and fuel switches. I had to be careful not to hit a switch by mistake!

Trying to keep my helmet from flying off at speed! Photo: Dino Sbrissa

We were on the circuit with other cars. Most of them were GT based cars such as Porsche GT3 cup cars and the like. So, we passed a lot of people in the few laps we did. Passing was kind of disconcerting as again the 333SP is so low, I found myself looking up at the door handles of the cars we were passing! A strange sensation for the uninitiated. As we zipped thru the traffic, the car just leaped from one corner to the next. The ride was a lot more brutal and jerky than it looks when just watching. The power allowed the 333 to cover distance very quickly compared to the other cars. I tried to imagine driving this car at the 24 Hours of Daytona, at night, trying to get through traffic. A mind-boggling thing to comprehend. As we drove, I tried to put myself in the driver’s seat. I thought, ok, would I stick my nose in this corner to pass this GT car? Most often the answer was NO! I asked Didier later how he knew these guys would not come over on us in the corner. His response, “My nose tells me, after many years of experience!” But I guess that is why he is the driver and I am the mechanic!

Riding in close proximity to other cars, in an open cockpit car you notice quickly the exhaust smell of the cars in front of you. No doubt this was due to my head sticking up in the airflow higher than the driver. Didier said it didn’t bother him, as the air goes over the drivers head due to the shape of the front windscreen.

Too soon, it was over, and we returned to the pits. I was left with the feeling that every race mechanic should take a few laps as a passenger in the cars they are working on. Very quickly, you begin to understand what is at stake here, and how fast you are going, what could potentially go wrong and what the consequences might be.

All in all, an incredible experience to ride in this historic sports racing car, at the famous Italian track which is owned by Ferrari. In the USA, we call this a definite “E-ride” (referring to Disney World’s rides ranging from A, the lowest and easiest to E, the most impressive). It was a short glimpse of what is possible and what most people never get to experience.

The 1981 24 Hours of Daytona shaped up to be another battle of Porsche 935s. The 935 had won the last three Daytona endurance races in a row starting in 1978. Although the 935 was based on a street 930, it was fast and reliable when properly prepared. Dick Barbour, after winning the IMSA championship with driver John Fitzpatrick in 1980, had stopped racing. That gave Bob Garretson the opportunity to continue with the same crew on his car in 1981 – a Porsche 935 (chassis 009 0030) which the team had built from a bare factory chassis in 1979. Bob had signed a new deal for 1981 to prepare the Cooke-Woods cars. This was a partnership between Roy Woods and Ralph Cooke. New Lola T600s had been ordered but would not be ready until later in the year, so the Porsche 935 would be run in the meantime. In any case, the Porsche would be more reliable for the 24 Hours of Daytona.

Team principal Bob Garretson just prior to the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981.

The car would be driven at Daytona by Bob, Brian Redman, and Bobby Rahal. We seemed to struggle a bit in getting everything ready and prepared up to our normal standards. We were still putting the car together at the track, missing a few practice sessions. We had to send Brian Redman out to qualify using the session as a brake pad bedding session, so we ended up only 16th on the grid. Brian, however, was happy with the car and told us not to worry, all was well for the race.

The race featured no less than 15 or so Porsche 935s or derivatives, as well as the factory Lancia team, running the 2.0-liter MonteCarlos in the World Championship. At the green flag most took off at high speed, pushing like it was a one-hour sprint race. It wasn’t long before engines were blowing up left and right. Many of these cars came into the pits to change engines, which was legal back then. Several went through two engines.

One of the 2.0-liter turbocharged factory Lancia Betas that ran against an onslaught of Porsche 935s in the 1981 Daytona endurance classic. This one was driven by Formula One standout Ricardo Patrese, along with Hans Heyer and Henri Pescarolo. They would finish 18th. Photo: Martin Raffauf

In contrast, we ran to our pace and soon were running at the front from the 16th starting position. At one driver change in the early evening, Brian was furious with Bobby Rahal, as he had taken the lead during his stint; Brian told Bobby he was pushing too hard! Bobby was apologetic and said, “I didn’t pass anyone, they are all falling out.” Brian wandered off muttering, “It’s too early, it’s too early.”

The Garretson Porsche 935 on the tri-oval during practice for the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981. Photo: Martin Raffauf

Around midnight, the Interscope 935 crashed with a backmarker and our car ran over some debris from the incident, which broke an exhaust pipe. This was quickly changed in the ensuing pit stop. By Sunday morning we were cruising and had a large lead of some 10-15 laps. Brian came in at about 6:45 am after a double stint, handed over to Bobby and asked, “Where’s breakfast?” Well, we said, nothing has been organized on that front yet. “Ok, he said, I’ll take care of it.” I remember thinking, how is he going to get breakfast? About 20 minutes later, Brian came back to the pits with bags of McDonald’s breakfast sandwiches. He had driven across the street to the McDonalds across from the speedway, still in his driving uniform, picked up food for the crew and had brought it back to the pits. He sat and ate with the mechanics in the pit, then went off to prepare for his next stint.

One of the friends of the team at this time, who was in our pit a lot, was Olivier Chandon, son of the French champagne house. By early Sunday, he began to get concerned, as he thought we would win, and there was crappy champagne on hand from the speedway for the Victory Lane celebration (in his view). The crew, of course, were not interested in any of this and ignored him, as we knew it was not “over until it’s over” as Yogi Berra used to say. We were just focused on making it to the end, not worrying about what kind of champagne we would drink, if any! In any case, Olivier was calling all over Daytona looking for Moet & Chandon but none was to be found. So, bless his soul, he jumped in a rental car, drove to Orlando, found the right stuff, and sped back to the circuit with the Moet & Chandon by noon or so.

The Garretson crew rushes towards the finish line to salute their car as it wins the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981. That’s the author on the far right in the blue overalls, raising his red hat in celebration. Race organizers were not pleased with this behavior and outlawed such displays in the future due to safety concerns. Photo: Peter Gloede

We ran off the remaining laps without issue and won the race. An Egg McMuffin paired with Moet & Chandon; does it get any better? It was a grand celebration and Olivier was happy he could provide “the proper champagne!” Sadly, Olivier lost his life a few years later in a Formula Atlantic crash at West Palm Beach. But we always remember and salute the Moet & Chandon!

Victory Lane celebrations were sweet in 1981 with the right champagne! Photo: Peter Gloede

Author: Martin Raffauf

All photos: Jerry Woods

Dick Barbour raced at the 24 Hours of Le Mans as an entrant for the first time in 1978, where he entered two Porsche 935’s in the special IMSA class at the classic French enduro. Barbour had started racing in IMSA in 1977 after having bought one of the original ten Porsche 934/5 models offered by the factory for IMSA racing that year. He ran some of the IMSA races with mixed success, but towards the end of the season, he and Bob Garretson signed an agreement that committed Garretson Enterprises to prepare Dick’s car(s) for the 1978 season.

Garretson Enterprises was an independent Porsche repair shop in Mountain View, California that had made a name for themselves in 1977 by preparing Walt Maas’ IMSA GTU championship-winning Porsche 914-6. The team entered eleven races that year and won eight of them, and finished second, third and fourth in the others, winning the championship over the factory Datsun 240Z of Sam Posey run by Bob Sharp. They had also prepared the winning car at the 1976 Pikes Peak hill-climb, a Porsche-powered buggy for Rick Mears.

Dick was looking to expand in 1978, so he ordered a new 935-78 (77A) for Daytona. His old 934/5 from 1977 would need some work and investment to update it to full 935 specifications. With Johnnie Rutherford and Manfred Schurti as co-drivers, he finished second overall at Daytona with the new car, after being delayed by a blown tire in the banking which lost a lot of time for repairs. For Sebring, two cars were entered, and although Dick’s main car faltered when a shock broke and punctured an oil line, the second car driven by Bob Garretson, Brian Redman and Charles Mendez (the race promoter), won the race. That car was immediately sold to John Paul Sr. after Sebring.

After Sebring, where I started with the team, we started preparing for two more US races, Talladega and Laguna Seca, then Le Mans. The second-place Daytona car (serial number 930 890 0033) ran at Talladega and finished third with Dick and Johnnie Rutherford driving. For Laguna Seca, we entered two cars, one for Dick, who finished sixth and one for Bob Bondurant (which was the updated 934/5) who ended up seventeenth. Then came the big push to get everything ready for Le Mans. In those days transportation for the car was usually done by boat, so a long lead time was required.

Although I was working with the team quite a bit by then, I was not going to the races (except for Laguna and Sears Point), as the traveling schedule had already been determined. I helped get everything prepared and loaded and then wished the team well. Steve “Yogi” Behr from New York (an IMSA racer from time to time) came and drove one of the trucks back to New York for us to get it to the ship, as there were no other people available to make the drive.

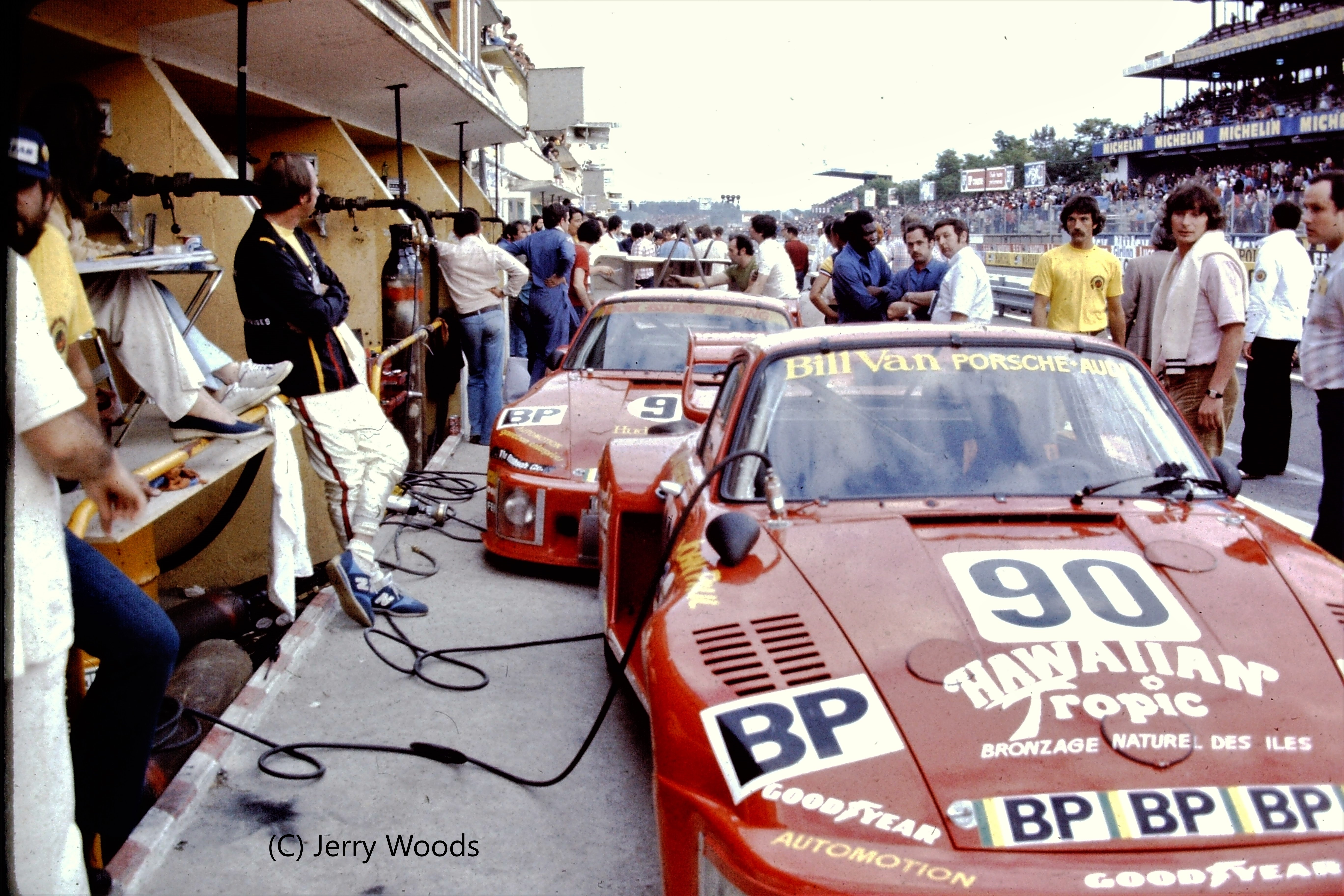

Dick had ordered a brand- new twin turbo 935 from the Porsche factory for the race. Gary Evans, the team manager, had gone over to Germany to order it earlier in the year (serial number 930 890 0024). Gary and Jerry Woods went to the factory to take delivery before the Le Mans race. It was then delivered to the track by Porsche with the rest of their cars. It would run as #90, and be driven by Dick, Brian Redman, and John Paul Sr. The second car, which we had prepared in California, was a Porsche 935 (serial number 930 890 0033). This 935 was a single turbo model and would be driven by Bob Garretson, Bob Akin, and Steve Earle.

Dick Barbour Racing picks up a brand-new Porsche 935 from the factory just prior to the 1978 24 Hours of Le Mans. Gary Evans at Left, Bob Garretson and Sharon Evans at right.

The majority of the team had arrived the weekend before and set up in the Le Mans paddock. Several of the team stopped on the way and watched the Spanish Grand Prix at Jarama. At the Madrid airport, they ran into none other than Bill France Sr. of NASCAR, who gave them directions to the circuit. Ron Trethan, Greg Elliff, Brian Carleton, and Alan Brooking watched Mario Andretti win the Spanish Grand Prix in a Lotus 79. Many years later, Greg Elliff would restore the very same Lotus 79 for Duncan Dayton. At the race, they ran into Bill Broderick (the hat swap guy in victory lane!) from Union Oil (NASCAR). After the race, at the airport, all the drivers had already arrived from the track via helicopter. They had a beer with Jody Scheckter while waiting for the plane to France. By the time they got to the team hotel in Pontvallain France, it was very late and the place was already shut down as everyone had gone to bed. They slept on the sidewalk in front of the hotel and were woken early by the street sweepers. I guess that’s what happens when you travel from Mountain View, California to Pontvallain France for the first time! Pontvallain was just not set up for “late arrivals.”

Dick Barbour Racing crew gets set up in the grass paddock at Le Mans in 1978. As newcomers, we did not get prime paddock space in 1978.

The Le Mans circuit back then was very different from today. The Mulsanne had no chicanes, and the pits were old, and quite decrepit. The signal pits were at the far end of the circuit, many miles away at the Mulsanne corner. Radios back then were problematic, and in any case, the American radios did not work too well in France and were technically illegal to use, as you were supposed to have a French license to use any radios. Communications to the signal pits were via old crank up phones on the wall in the pit boxes. Paddock and team working conditions, were basic at best. Much of the paddock was not even paved, and as “newcomers”, the team got a prime grass corner in the back. The hotel was a small one in the town of Pontvallain which was well to the south of Le Mans, about a one hour drive.

The car as delivered by Porsche, needed some work to become IMSA legal as the rules for FIA Group 5 and IMSA were slightly different. IMSA rules required windshield retaining tabs, rear window straps, and a driver’s window net. New front air dams that had been built in California were fitted. These had been built by Jeff Lateer, and contained two headlights per side, thereby alleviating the need for the night hood mounted extra lights (lessening drag on the Mulsanne). The delivered drilled brake rotors were removed and replaced with longer lasting solid rotors.

Both Dick Barbour cars sit in the pits at Le Mans prior to the start of the 24-Hour classic.

Both cars were entered in the IMSA class, along with a bunch of Ferrari 512BBs, a few RSRs, one BMW CSL, and Brad Frisselle’s Monza. There were Group 6 prototypes from Both Porsche (936) and from Renault, as well as Mirage. These would be the cars to beat for overall victory. There were also quite a few Group 5 Porsche 935s and Group 4 Porsche 934s as well as 2.0-liter sports cars. All the 935s ran the 3.0- liter engine, some twin turbo, some single, except for the 935-78 from the factory which ran a 3.2 engine with water cooled heads. All the Group 5 935s weighed less than the IMSA version, as we had to run at the IMSA minimum weights to run in the class.

Both our cars qualified without difficulty. Redman got the pole in the IMSA class with a 3:52.6, Dick did a 3:56.6, and John Paul Sr. a 4:02. Bob Garretson qualified the #91 at 4:05, Bob Akin at 4:09 and Steve Earle at 4:13. Rolf Stommelen set a blistering time in the 935-78 of 3:30.9 to start third overall behind Ickx in the 936-78 at 3:27.6, and Depallier in the Renault at 3:28.4. The battle for the IMSA class would come down to our two cars, and most likely the Ferraris of Charles Pozzi and NART. Dick, having finished second at Daytona, was in an advantageous position to win the Daytona-Le Mans trophy for 1978. This trophy was awarded to the driver/team who did the best in the two races combined. Since the Brumos (Peter Gregg) team, which won Daytona, was not running at Le Mans, Dick just had to finish well up and he would get that trophy. That was a secondary goal of winning the IMSA class.

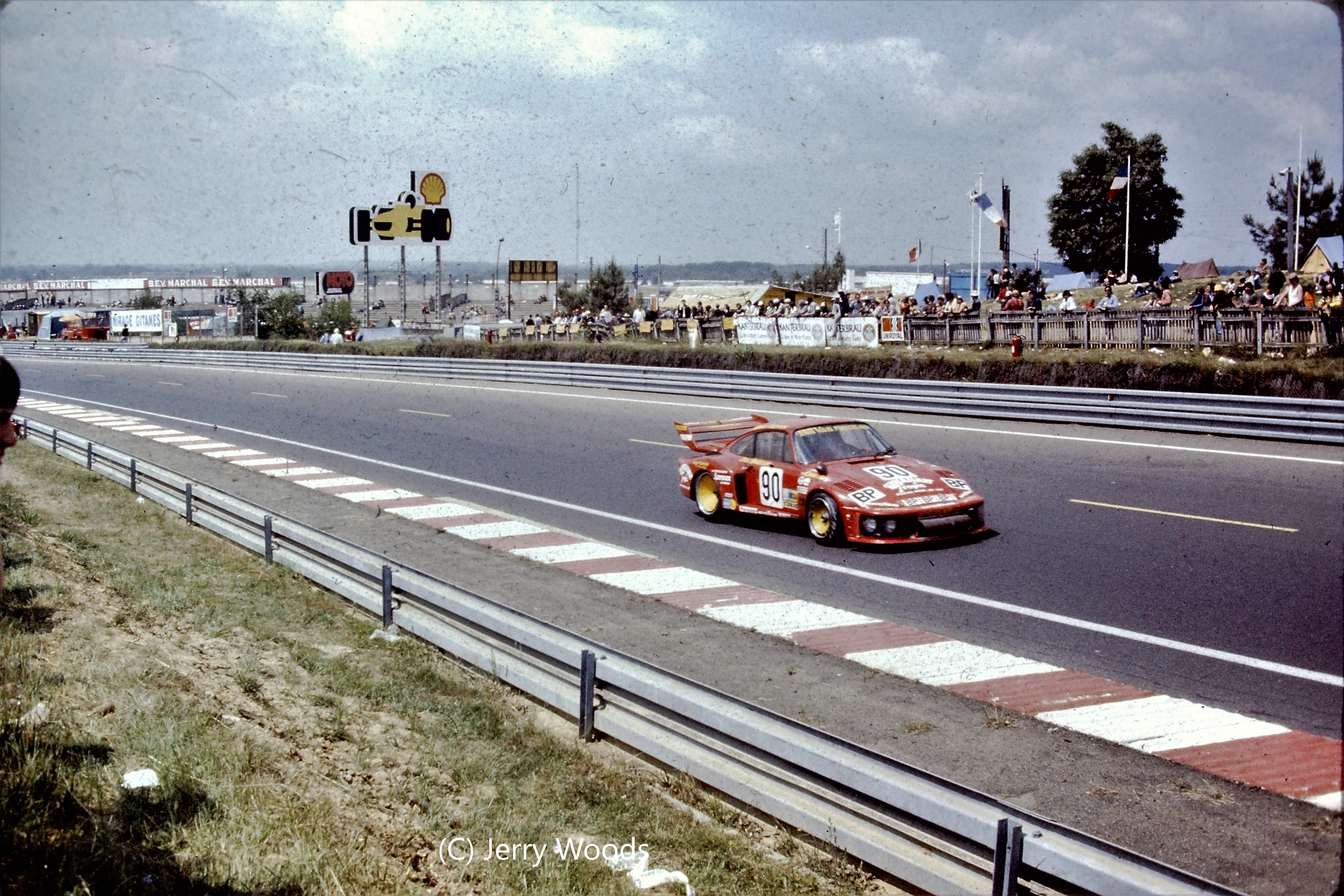

The number 90 Porsche 935 at speed at Le Mans in 1978. The car was shared by Dick Barbour, Brian Redman, and John Paul, Sr. and would win the special IMSA class that year.

The race started well enough. The strategy was to drive conservatively, finish, and win the class. Starting in the early stages, the #90 led the class and ran like clockwork. The #91 had a few issues, including troubles changing brake pads and a crash by Steve Earle, which required new front fenders and air dam. Around 3:50 am Sunday, #91 had an issue with the exhaust system, and 14 minutes were lost, but the car was still running. At 4:55 am Sunday, Bob Garretson went off the road at the Mulsanne kink, vaulted end over end on the side of the track on driver’s left. He doesn’t really remember what happened, and although he was dazed, he walked away from the crash. About the only thing he recalled was that the door was so smashed he had to crawl out thru the windscreen area. The windshield was gone completely. The car was pretty much destroyed. Brian Redman stopped at the site in the #90 car, checked to see if Bob was ok, then pitted to give a report to the rest of the team. Several of the crew went out to the crash site once it became daylight, and found Bob’s glasses in the dirt by the car.

The number 91 Porsche 935 wasn’t so fortunate, having crashed at high speed on the Mulsanne straight in the middle of the night. Driver Bob Garretson escaped unhurt, although he had to crawl out the hole the windshield used to occupy. The car was almost completely a write-off.

By the time we got it back to the shop in California, about all that was salvageable were a few gauges from the dashboard, some of the engine parts, and some of the gearbox parts. Most of the suspension, bodywork, chassis, roll cage etc. was all trash.

The #90 car ran trouble-free, just making normal pit stops for fuel, tires and changing of brake pads. The only real issue occurred at one point when team manager Gary Evans went looking for Brian Redman to get him ready for the next pit stop. He was getting worried when he didn’t find him in any of the driver caravans, which were all full of sponsors and others who weren’t supposed to be in there. Eventually, he was found sleeping in the canvas tire slings in the truck – disaster averted.

Brian Redman catches a nap between stints. Everyone, even the drivers, had to grab sleep when and where you could find it.

Since John Paul Sr. was driving with us, he brought his main mechanic, Graham Everett along. He and Greg Elliff changed the brake pads and did it well. According to Le Mans records, not one stop for this car was longer than two minutes. Even the Porsche factory guys on the 936 next door to us were impressed, as the #90 car was changing brake pads quicker than they were. Most of the race we were in a battle with the Group 5 leader, which was the Kremer car of our IMSA buddies Jim Busby, Rick Knoop, and Chris Cord. In the end, we finished fifth overall and won the IMSA class, and they finished sixth overall and won the Group 5 class. The Porsche factory at Werks 1 – Zuffenhausen had certainly done an outstanding job building 930 890 0024. Not one issue, and a class winner, first time out. The drivers did an excellent job and avoided any on-track issues, and the pit work was exemplary.

Dick Barbour had accomplished both goals – winning the IMSA class and winning the Daytona-Le Mans trophy for 1978. After that experience, he was hooked and would return to Le Mans again in 1979. But that’s another story.

Reprinted with Permission from PorscheRoadandRace (www.PorscheRoadandRace.com)