The months of April and May bring sad reminders of three great F1 heroes lost to crashes – Jimmy Clark, Gilles Villeneuve and Ayrton Senna. All are sorely missed. We can be grateful that Niki Lauda, whose passing in May of 2019 was a reminder of a long and inspiring life, escaped from his fiery crash at the Nürburgring. Yet, it was not until the fatal crash of Senna in 1994 that a safety revolution took place. This excerpt from “CRASH!” looks at why the great Brazilian’s death made so much difference when it came to racing safety, now part of his legacy.

The Death of Senna

Those in racing who were closer to Senna tended to present him in a more nuanced light. One of those was Dr. Sidney Watkins, the head of neurosurgery at the London Hospital. The medical officer of Formula 1 was known as Professor or “Prof” Watkins. He became a friend and confidant of the Brazilian driver, who arrived not long after Watkins first took responsibility for ensuring a prompt medical response to drivers involved in crashes. (This was at the behest of Formula 1’s hard-driving businessman Bernie Ecclestone, who perhaps foresaw the need for greater safety and the politically risky prospect of drivers getting killed during the live TV coverage he was so instrumental in organizing.)

Watkins, in his book “Life at the Limit, Triumph and Tragedy in Formula One,” recalls the time when Senna made a visit to the Loretto School, Scotland’s oldest boarding school located near Edinburgh. Watkins’ stepson Matthew Amato was enrolled at Loretto and had requested a visit from Senna in a letter that was hand-delivered by Watkins.

There was great interest in Formula 1 at Loretto. Jim Clark, the two-time World Champion, had attended the school and the Clark family’s farm was located in the rolling hills of the nearby Borders district. Senna’s visit came prior to the start of the 1991 season and shortly after he had won his second World Championship—– the one he had clinched by intentionally taking Alain Prost off the track in Japan. After walking through the memorial to Clark in the chapel, Senna addressed the high school enrollment during the mandatory bi-weekly Saturday evening lecture, which usually featured speakers from industry or medicine.

“We thought Ayrton would be a good one to have,” recalled Amato in an interview 20 years later. He was 15 at the time he requested the visit by having his stepfather deliver the letter to Senna. “He gave a really good talk about what it takes to be a Formula 1 driver and about Jim Clark. He said he liked the fact that Jim Clark always had a smile.”

The bulk of the lecture was a question and answer session and the first question came from a future barrister. It was about rival Prost and what he thought of him? “Wow, first question!” said Senna, who went on to praise his rival in some detail.

“It was the etiquette that we had to address the lecturer as ‘Sir’ before we asked a question,” said Amato. “About three or four questions in, he said, ‘You don’t have to call me sir.’ The next question he got, the guy called him ‘Ayrton,’ and he said, ‘Yes, like that.’ By the end, everyone was calling him Ayrton. He answered a lot of good questions about the pressures of the job and even about sponsorship by tobacco.

“He gave very good, thoughtful answers, which I think is not a given for many sportspeople. He was very comfortable talking about his faith in God. It was more from the perspective of answering questions about the danger of his job and was he scared of losing his life? He said he had faith and that helped.”

If there was a comparable driver to Senna, it would have been Clark. Along with Alberto Ascari, they were the three Formula 1 champions considered truly great who died in their race cars.

Clark won everything worth winning, including the Indy 500 and two World Championships. His fame invariably preceded him, but Clark, who became the youngest Formula 1 champion when he won the 1963 title, sustained a down-to-earth outlook more fitting of the mechanics who worked on his cars, an attitude one might expect from the son of a Scottish farmer.

On the track, Clark’s hallmarks were all-round skills and success in a variety of cars, head-and-shoulder dominance of Formula 1 and an ungodly ability to coax speed from even the most ill-handling or demanding machines.

He had an easy manner and smile, but Clark detested the hoopla surrounding such events as the Indy 500. “I started (racing) as a hobby with no idea and no intention of being world champion,” he said in some rare video footage, “I wanted to see what it was like to race on the track.”

Jimmy Clark confirmed his legacy as one of the all-time greats by winning the Indianapolis 500 in Colin Chapman’s Lotus chassis. (Photo courtesy of The Klemantaski Collection)

Apparently, Clark was happiest behind the wheel plying his other-worldly skills. He raced practically non-stop, spending his winters Down Under driving in the Tasman Series for Formula 1 cars, winning the championship in a Lotus 49T in 1968 and presaging what many expected would be a third world title. He drove anything, including a Lotus Cortina taken to the championship in the British Touring Car Series and even a Ford Galaxie at the North Carolina Motor Speedway in a NASCAR Grand National event. He was on board a Lotus Formula 2 car at the Hockenheim circuit in Germany when a suspension failure on his Lotus chassis sent him off the track, into the trees and to his death from a broken neck and skull on April 7, 1968.

In a response eerily similar to the death of Senna 26 years later at Imola, fans and participants in the sport found it hard to believe Clark had died. During a sports car race, an announcement about the crash was made at the Brands Hatch circuit in England where Clark had scored the 1964 British Grand Prix victory. “The place was stumped,” said future racing executive Ian Phillips, a teenager at the time. “People were just staring blankly at one another, standing about in complete and utter silence. The whole place went numb, really.”

The day Clark was killed, he was driving a Lotus chassis in the gold, red and white livery of Gold Leaf Tobacco Company, not the traditional green colors representing Britain that had been used by Lotus and team owner Colin Chapman previously. It marked the beginning of the commercialization of Formula 1, the initial step away from being considered a sport by participants. Instead, it would soon be looked upon as a sport that needed to run itself as a business.

After Clark’s death, there was concern the sport would be outlawed due to the obvious lack of safety represented by the fatal crash of its greatest driver. But the absence of scale when it came to motor racing’s popularity and the lack of broad commercial involvement precluded any great backlash. The tragedy was significant enough to warrant a same day announcement in America on Wide World of Sports by host Jim McKay, who was the broadcaster for the Indy 500 during Clark’s assaults on the Speedway. But regular live TV coverage of Formula 1 was still years away. That, too, helped keep in check the tide of public criticism about the dangers of motor racing.

Almost a decade later, when Niki Lauda crashed at the Nürburgring at the German Grand Prix in 1976, the incident generated a hail of news coverage in racing trade publications. Despite the high-profile of Lauda’s crash, the effort to change the odds in favor of safety ran up against the acceptance and admiration by the racing culture, which held that racing at high speeds necessarily carried inherent risk. Instead, the focus was on giving medals to the two drivers who helped pull Lauda from his burning Ferrari, his gusty return after only six weeks, and James Hunt’s incredible comeback in the season finale at Mt. Fuji to win the title – where Lauda withdrew due to unsafe conditions. The wire services had also covered the crash at the Nürburging, but the general public viewed it as just another motor racing incident.

Six years later, when the much loved, free-spirited, and effervescent Gilles Villeneuve died in Belgium on board a Ferrari during a balls-out qualifying lap, it shocked and saddened the racing world, but did not take it by surprise. Similarly, when Villeneuve’s brilliant young counterpart in rally driving, Henri Toivonen, fatally crashed in Corsica four years later, shock mixed with grief, but the fatal crash was not totally unexpected. The FIA summarily banned the Group B cars used in rallying at the time of Toivonen’s death—the so-called Killer Bs. Otherwise, not much political fallout occurred.

By contrast, the death of Senna, whose estate was valued by some as high as $400 million, occurred when commercialization was in full bloom. His crash in a car powered by Renault and sponsored by the Rothmans International tobacco company was beamed into homes, bars, motor homes, and public houses globally, the same medium that had made the Brazilian driver a leading light in the daily march of sports heroes across TV screens everywhere.

Max Mosley, the FIA President at the time of Senna’s death, had competed in the Formula 2 event in which celebrated champion Clark was killed. In fact, it was his first race. Mosley, a man who believed strongly in individual choice, continued his driving efforts and later became a part-owner of the March Engineering team in F1. As the FIA’s leader, he found himself stunned by the backlash from the media and the public in the aftermath of Senna’s fatal crash.

Major newspaper editorials in Europe expressed doubt about a sport that could kill one of its champions. The racing trade publications blamed the FIA. Even the Vatican weighed in, characterizing F1 as contrary to the human spirit. At first, Mosley backed the risk-taking in F1, saying that mountain climbing and other sports offered the same challenges. But when Karl Wendlinger suffered a severe concussion in the first practice session at Monaco, which left him in a coma, it followed three critical or fatal head injuries at Imola, including the deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Senna. Mosley changed his perspective overnight and made a major decision on safety.

A half-century after the shift began to permanent circuits to protect fans as a result of public outcry, the FIA was forced to radically change course to protect the sport from political backlash again. This time, the focus was on making the safety of drivers an unquestioned priority.

(Editor’s Note: Jonathan Ingram is in his 44th year of writing on motor racing. His current book is “CRASH! From Senna to Earnhardt — How the HANS Helped Save Racing.” Visit his website for other blogs and special pricing for “CRASH!” during the economic slowdown — https://jingrambooks.com/industry-book/crash )

On the last Sunday afternoon in May of 1994 at the Charlotte Motor Speedway, John Andretti stepped off a helicopter, which had brought him from a tenth-place finish in the Indy 500 earlier in the day, and began his walk across the front stretch grass toward the pit road and an awaiting Chevy that he would drive in the Coca-Cola 600.

The helicopter had set down in front of a grandstand jammed with 140,000 fans, primed for the beckoning start of the 600-mile race. The fans let out a huge cheer once Andretti appeared. Now in his NASCAR driving suit, Andretti may have “bulked up” on intravenous fluids during the trip from Indy. But the moment remained enormously impressive—a lone driver, all of five-foot-five, bringing down the house by merely walking across the grass.

That was the beginning of a long and successful stint in NASCAR’s premier series for the only member of the Andretti family to work regularly in Indy cars and what was then known as the Winston Cup. He was also the only member of his clan to win the prestigious 24-hour sports car race at Daytona and to clock within a hairbreadth of 300 mph in a Top Fuel dragster.

The sports car and drag racing exploits had been accomplished before Andretti invented the Memorial Day weekend double. He teed himself up to drive an A.J. Foyt-owned Lola-Ford at the Brickyard and one of Billy Hagan’s Chevy Luminas for the 600-mile second leg in Charlotte. On the biggest day of racing in America, the diminutive Andretti won the hearts of fans everywhere. It was a calculated move by Andretti, in part, who also gained the attention of those hardened sports editors at major American newspapers who only gave racing a major space allocation on the last Sunday in May due to the huge crowds at Indy and Charlotte.

Far from a stunt, this was the real deal. People were electrified about Andretti’s arrival in Charlotte and the drama continued in a TV interview with Kenny Wallace, a relative newcomer to the broadcast side of the sport. An up-and-coming driver as well as announcer, a nervous Wallace greeted Andretti on the pit road and goofed big time by calling him “Jeff,” the name of his cousin. John took it in stride, referring in deadpan to his TV interviewer as “Rusty,” which, of course, was the name of Wallace’s older and more famous brother. It was a typical moment for the smiling Andretti, his humor undeniable and disarming, delivered in the enormous glare of the moment.

Having known him since he was 23 years old, it came as little surprise that John would eventually top that major career day in Indianapolis and Charlotte.

Andretti celebrates his first Cup win along with the Yarborough team at Daytona. Photo: Daytona International Speedway

He didn’t top it by later winning a summer Cup race at Daytona for team owner Cale Yarborough or by winning at Martinsville for team owner Richard Petty, or by winning poles at Darlington and Talladega. He didn’t top it by pursuing an ongoing bout with the Indy 500, where he raced 12 times and suffered the ill fortune that has followed the Andretti clan at the Brickyard. (Cousin Michael led the most laps of any driver who never won the race; John suffered a different type of family luck, failing to land enough rides capable of leading the field, a prerequisite to winning.)

At Indy, Andretti scored two Top 10 finishes with the Hall/VDS team in 1991 and 1992. Photo: IMS

Eventually, John would top his Indy-Charlotte double and an impressive career across multiple disciplines by how he faced the fact he was diagnosed with colon cancer in his early fifties. He stepped up big time by publicly engaging a problem faced by many who were dodging the well-known, but often shunned, method of early detection—a colonoscopy once every five years after the age of 50. By creating the hashtag #CheckIt4Andretti and speaking publicly about his illness, John knew he could make a difference.

“That’s the only reason I went public,” he later confided to a writer for a medical magazine called Coping with Cancer. “Because I really didn’t want people to know. I don’t want people to feel sorry for me.” Even now, trying to walk a mile in his shoes, it’s difficult to fathom how hard it must have been for such a proud man to publicly admit he could have avoided a painful and often deadly form of cancer by choosing the standard medical screening.

In round one, John beat the cancer following dastardly difficult surgery and chemotherapy. But as cancer often does, it returned with a vengeance. John fought bravely. We know this from the many accolades and tributes from those familiar with the final year of struggle before his death at age 56.

Andretti, aged 23, paired with Davy Jones and BMW to score his first IMSA Camel GT win at Watkins Glen in 1986. Photo: Tony Mezzacca

It was almost impossible not to like John Andretti. I had first met him while he was driving a GTP car for the BMW factory team shortly after he had graduated from Moravian College (and simultaneously raced USAC midgets at the Indianapolis Speedrome). Near the end of that 1986 season, at age 23 he scored a major victory for BMW in a co-drive with Davy Jones at Watkins Glen. Even then, Andretti had a disarming manner and was outgoing in a way that really engaged people—which he always seemed to enjoy. His perspective was his own and invariably unique, as later witnessed by his response to colon cancer.

It can be odd, sometimes, how a friendship strikes up. John had what might be described as an Italian temper as well as temperament, the latter being about a capacity for the joys of life and an individualistic viewpoint. As for the temper, it was easy to tell when John was angry. As far as I knew, it didn’t happen very often. But when angry, John lit up like a bulb. One day during an IMSA race weekend, he was considerate enough to lower the boom where nobody else could hear us. “When I read your race reports,” he said with a generous amount of heat, “it’s like you think everybody else on the team is responsible and I’m just along for the ride.”

John posted his first major victory at the Rolex Daytona 24 in 1989 with the Busby team, co-driving with Bob Wollek and Derek Bell, all the young age of 25. Photo: Peter Gloede

This conversation took place during IMSA’s 1989 GTP season when John was paired with Frenchman Bob Wollek on the Porsche 962 team owned by former star driver Jim Busby and sponsored by Miller beer and B.F. Goodrich. The team had won the season-opening 24-hour, where Derek Bell had been part of the three-man driving crew. Thinking back to when Davy Jones co-drove with John in what turned out to be the crucial stints in the BMW victory at Watkins Glen in 1986 and then considering the 24-hour win at Daytona, co-driven with Wollek and Bell, I realized John had raised a valid point.

“Brilliant” Bob, as Wollek was known, was regularly hired by factory teams for his deep understanding of tires and chassis. He had a Machiavellian way of dealing with journalists, alternating mild sarcasm with approachable friendliness and then, inevitably, angry tirades. Bell, the Brit who won his eighth 24-hour between Le Mans and Daytona that year, had an established reputation. The young Andretti, on the other hand, was still proving himself in my eyes, which I realized may have been a mistake, because I was paying too much attention to other story lines. At Daytona, this included John’s scheduled start in a sister Busby Porsche with cousin Michael and uncle Mario. That car departed early, allowing John to switch to what became the winning machine initially driven by Wollek and Bell.

“OK, John,” I told him, “I understand what you’re saying. From now on, I’ll pay closer attention.” I talked with a trusted member of the Busby team and got more details about John’s role entering the fifth race of the season. Then, John delivered. He and Wollek won that weekend on the fairgrounds circuit at West Palm Beach against a deep field of Porsches, two Jaguars entered by TWR and the Nissan of Electramotive. My story included this line: “Andretti was not only instrumental in setting up the Goodrich-shod Porsche, he nearly matched Wollek’s times in the race that ended Electramotive’s three-race winning streak.”

Although drivers make their own way, racing magazines always made an impression. That’s what John was angling for, understandably, the kind of third-party information in the media that would help him get a good ride in a CART Indy car. If John got a ride in CART, which he did, that was up to him. But I had to admit he had nailed me on initially adopting a wait-and-see attitude about him during the inevitable cacophony of GTP races with multiple contending teams and co-drivers. Had I fallen guilty to thinking he got the ride in the BMW and the Busby Porsche just because of his family name? Had I doubted his sports car endurance ability due to his diminutive size? Where his cousin and uncle were short and stout, at that time John was a similar height but slender by comparison, almost wispy at 135 pounds.

I’ve had young drivers tell me how wrong my reporting was and then declare, “I’m never speaking to you again.” They’re the type that usually sabotages their own career in equally disastrous relationships with teams and co-drivers. But after the West Palm Beach victory, John went back to being outgoing, engaging and funny whenever I saw him, bearing no hint of a grudge or the usual frostiness of drivers after swords have been crossed. As it turned out, our careers advanced along similar lines. John landed an Indy car ride in the legendary Pennzoil colors of Jim Hall, winning out of the box in Australia in 1991. I added the Atlanta Journal-Constitution to my publications list, the largest newspaper in the Southeast and the largest that regularly covered NASCAR. The paper sent me to Indy in 1991, where John joined uncle Mario, cousins Michael and Jeff in the starting field; John scored his best-ever finish of fifth in that year’s 500.

In the year of his double, I covered the final leg in Charlotte. In the previous year, the newspaper had me covering local drag racing, which meant reporting on John clocking 299 mph in the Southern Nationals at the Atlanta Dragway and winning two rounds in Top Fuel, before bowing out in the semi-final round of eliminations. At the time, John was an out-of-work, young race car driver who had taken the extraordinary step of doing something completely different to keep his name—and skills—in front of the racing community. It could not have been as easy to adapt to the high-powered, finicky Top Fuel machines.

The money soon ran out on the drag racing side, but then John landed a full-time gig in NASCAR as a result of the Indy-Charlotte double, once again taking it upon himself to call attention to his talent, stamina and media appeal, which led to 393 career Winston Cup starts, including 15 in the Daytona 500.

Looking back, John had driven in IMSA sports cars and taken the journeyman ride in Top Fuel to demonstrate his ability with high horsepower cars, which for young drivers was a prerequisite to entering the major series that included deeper fields and stiffer competition. If people thought maybe he wasn’t big enough or strong enough to handle major 500-mile races, it occurred to John how he might change the minds of potential team owners and sponsors. He could give himself a better opportunity to land a ride in either Indy cars or NASCAR if he created and pulled off the Memorial Day weekend double. We never talked about it, but looking back, it seems I was not the only one who had doubted this Andretti early in his career.

Not only did John and I continue to cross paths throughout his days in NASCAR, but I also got to know his father Aldo, the twin of Mario. Aldo frequented NASCAR events to watch John race, often getting around to various parts of the track to observe on his own. In conversations with Aldo, I could see where John got his insightful and wry view of the world. His father had suffered a head injury that forced him out of racing while Mario continued and achieved worldwide fame. Despite his misfortune, Aldo retained a generosity of spirit and ability to handle life’s fate with pride and humility, two attributes that run deep in each of the twin brothers whose fates were so disparate. Although he never achieved the considerable heights of his uncle or cousin Michael behind the wheel, John not only made his father extremely proud, but sustained those twin pillars of pride and humility.

As far as the world knows about the second half of his double in 1994, for example, the engine expired in his Chevy after 220 of 400 laps. The fact was that John hit the wall to bring out the first caution, which damaged the radiator and later the engine. He didn’t make any excuses, such as starting in the back after qualifying ninth, because he had missed the mandatory pre-race drivers’ meeting. “I was really loose,” he said. “It’s a tough job driving a loose car and I was hoping for a yellow. Unfortunately, it came out for me.” He soldiered on, eventually completing 830 miles of racing that day and night.

Once his driving career was over, John found himself in a world where racing had evolved into a TV-enriched state. Appearance fees started reaching five figures, even for retired stars. John, who always seemed to draw energy from those he engaged as well as give it, chose his own way. He continued to voluntarily raise money for the Riley Children’s Hospital, where he regularly visited with patients and their families, by promoting the “Race for Riley” go-kart event. He also helped promote son Jarett’s sprint car career.

The signature car design known as ‘The Stinger’ raised $900,000 for charity. Photo: unknown

John promoted the Indy 500 through the “Stinger” project, a modern car built in homage to the Marmon Wasp that won the first Indy 500. It was a joint effort by John, the Andretti Autosport team of cousin Michael and Window World, one of John’s longtime sponsors. When necessary, John traveled with the car around the U.S. to gain signatures of as many living Indy 500 veterans as possible, including every winner, before it was sold at auction in 2016 after the 100th running of the Indy 500, raising $900,000 for the St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis.

In another twist of fate for me, John and cousin Michael launched a go-karting facility in the Atlanta area, once again establishing a common link. After this first one closed, Mario eventually joined them and the trio later helped launch a new state-of-the-art indoor karting facility in Marietta, just up the road from Atlanta. The night of the opening, I had a car problem and missed the Andrettis by a matter of minutes after locating a back-up vehicle and dashing through the snarl of Atlanta’s rush hour. Looking back, how I wished I’d had one more chance to say hello in person away from the hectic environment of a race weekend. As it was, I later called John and talked with him about the karting business on behalf of a friend looking to get into that line of work. We had a long, engaging conversation, including talk about the ongoing “Stinger” project, because John always had time for people.

When fate called on him early, John answered with the #CheckIt4Andretti campaign. In the initial treatments, John shared his story on TV with local Indianapolis sportscaster Dave Calabro, helping to leverage his message. After an all-too-brief hiatus of cancer-free status, he and wife Nancy then focused on the private side of his medical struggle and on their children, including son Jarett and his sprint car career, and two college-age daughters. John vowed to see both daughters graduate.

John and Nancy never stopped sending out Christmas cards. They probably sent more than anybody in U.S. racing, cards that were high-quality and featured a family photo. As a result, each year I’d see their children growing up, experiencing the pride John and Nancy felt about their family while taking note of their understated religious conviction. The cards, including this year’s version that showed a smiling John, have been a yearly reminder of how John always did things his way.

(Editor’s Note: Jonathan Ingram is entering his 44th year of covering motor racing. His sixth book “CRASH! How the HANS Device Helped Save Racing” is in current release. To learn more and see excerpts, visit www.jingrambooks.com.)

For a guy who recently finished a book on some of the deadliest years of professional racing—and the safety revolution those years spawned—I felt strangely numb the day after Ryan Newman escaped from his finish-line crash at the Daytona 500. A brutal series of events, the crash included four different circumstances in a couple of seconds that could have potentially killed the driver.

The end of this Daytona 500 was like a near-death experience, except not your own. Once the thankful outcome became certain, there’s an aftermath. Relief comes first and before nagging doubts finally pass in one last shudder of horror.

On Tuesday the day after, I found initial relief in some thoughtful online comments plus the professional work of a couple of fellow commentators. Writer Ryan McGee and broadcaster Ricky Craven helped sum up that whole oddball process of a brilliant racing enterprise, invariably part ritual and part magic, turning into something else.

Those two summed up the nagging doubts that creep in when the close-to-the-bone nature of racing gets revealed and how the sport’s community of participants and fans face up to the reality of the mechanized, ritualized danger. Oh, there was plenty of standard stuff out there, too. Some expressed their doubts by criticizing the drivers—or NASCAR for how it operates the races on the Daytona and Talladega tracks. Some took it as an opportunity to express envy disguised as sarcasm because NASCAR’s stock cars and drivers are so popular compared to their own preferred style of racing.

In fact, the Daytona 500 requires each driver to make critical split-second decisions at sustained speeds of 200 mph every lap. If it becomes a race of cautions and attrition, well nobody complained in the years when only three or four drivers finished on the lead lap.

I felt lifted, and fully relieved, at the end of the day on Tuesday when I came across one road racing photographer’s Facebook post that was a funny take on his family members’ relative lack of racing knowledge. It underscored that everybody, not just race fans, were talking about Newman’s crash. (This was a particularly poignant as well as funny post considering the family has been fighting, successfully, alongside a teenage son in his battle with cancer.)

The potential for gut-wrenching outcomes have always been there in racing and will continue. Newman’s crash, for example, was a reminder of Sebastien Bourdais’s head-on collision with the barrier at Indy during qualifying for the 500 in 2017 at a speed of 227 mph. The difference was the French driver, who suffered a fractured pelvis and broken hip, remained conscious and alert afterward, immediately easing fears of the worst-case scenario. By contrast, it took almost a week for Newman to release a statement that he had suffered a head injury and would return to full-time status pending a medical clearance.

The replays of Newman’s finish-line crash will be repeated ad infinitum—because the driver survives to tell about it. I like this element, given that I wrote a book titled “CRASH!” containing voluminous research on how the safety revolution brought racing to the point where this kind of crash can be survived.

The safety revolution occurred across all the world’s major racing series. It started in Formula 1 with the death of three-time world champion Ayrton Senna in 1994. CART simultaneously began making major safety improvements after the injurious crash of two-time world champion Nelson Piquet during practice at Indy; CART became the first to mandate the HANS device prior to the 2001 season. The movement then came to NASCAR as a result of four driver deaths over a nine-month period, including Dale Earnhardt’s last-lap crash at Daytona. Given that these series operate in their own orbits and fans often do likewise, very few fully recognized how the safety revolution actually occurred. And how decisions in all three of these series helped make it happen.

The book is subtitled “From Senna to Earnhardt” for this reason. One could argue that their deaths—the great F1 champion from an errant suspension piece and Earnhardt from a basal skull fracture—during races watched by tens of millions of fans on live television were the two biggest events in motor racing in the last 100 years. After a full century of professional racing where death was commonplace, organizers realized, as we all did at this year’s Daytona 500, the sport simply could not be sustained if it continued to kill its drivers on live television.

There’s a touch of controversy to the book because it’s based on the idea that the brilliant work of so many dedicated racing professionals to achieve the safety revolution might have faltered absent the HANS Device. That’s the organizing principle of the story and the reason for the other subtitle: “How the HANS Helped Save Racing.” I worked directly with HANS inventor Dr. Robert Hubbard and his business partner, five-time IMSA champion Jim Downing, to write the book. But the thesis is entirely mine. Resolving the issue of basal skull fractures was the one thing sanctioning bodies could not figure out entirely on their own. During the 1990s, this type of injury was the most frequent cause of death or critical injury in all forms of major league racing around the world.

There’s no doubt all the elements of safety developed by NASCAR came into play on this year’s Monday running of the Daytona 500. The cockpit safety cocoon with its carbon-fiber seat, six-point harness, the head surrounds and a head restraint were the first line of defense. The SAFER barrier did its job—which includes sufficiently reducing g-forces so that the cockpit restraints could do their job without being compromised. The impacts of Newman’s Ford getting hit in the door and then the final impact of landing on its roof – in addition to the initial impact with the wall – all showed the value of NASCAR’s Gen 6 car construction requirements.

When it comes to safety, NASCAR operates from its own dedicated Research and Development Center in Concord, N.C., which makes it the world leader. (The FIA’s Formula 1 and IndyCar must rely, in part, on vendors instead of a fully equipped staff under one roof.) Although it’s not really feasible, I, for one, would like to see the in-car video from Newman’s cockpit taken by one of the recent innovations of a digital camera installed to observe what happens to the driver during a crash.

It’s not as if the safety revolution stands still. F-1 has introduced the life-saving Halo and IndyCar enters the 2020 season with the first generation of the Aeroscreen in place. Roger Penske’s ownership may yet lead to improvements in track fencing for open-wheel cars. Competitors to the HANS have emerged and the cost of a certified head restraint continues to decrease without a compromise in safety. (My favorite new arrival is the innovative Flex made by Schroth.) Weekend warriors can no longer offer the excuse that head restraints, which are needed in all forms of auto racing, are too costly, too uncomfortable or don’t fit in their vehicle.

History reminds us that far too many drivers died while Rome was burning and before the major sanctioning bodies recognized they needed to apply their technical and financial resources to greatly reduce the chance of death behind the wheel. The sanctioning bodies realized they had to act to save a sport dependent on the fan appeal of star drivers and dependent upon participation by car manufacturers, TV networks and corporate sponsors. This Daytona 500 was a reminder they did the right thing.

(Editor’s Note: Jonathan Ingram is entering his 44th year of covering motor racing. His seventh book “CRASH! From Senna to Earnhardt—How the HANS Device Helped Save Racing” is in current release. His Amazon bio is located at https://amzn.to/2wwPQ3V . To see “CRASH” excerpts, visit www.jingrambooks.com.)

The 20-year struggle by Dr. Robert Hubbard and Jim Downing to gain universal acceptance for their life-saving HANS Device—now in use by over 275,000 competitors worldwide—is an amazing tale of family, genius, perseverance, tragedy and triumph. It tells how the world’s leading auto racing series shouldered the task of saving their driving heroes—and a sport. Excerpted from the book CRASH! by Jonathan Ingram (with Dr. Robert Hubbard and Jim Downing), this is the story of Jim Downing’s awakening to the very real dangers of high-speed frontal impacts and his resolve to do something about it. The full book can be purchased here.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Chapter 2. Downing’s Awakening

A five-time road racing champion, Jim Downing first met Dale Earnhardt in the NASCAR hauler at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 2000, where he was talking about the HANS Device to a longtime acquaintance, Mike Helton, soon to be named the NASCAR president.

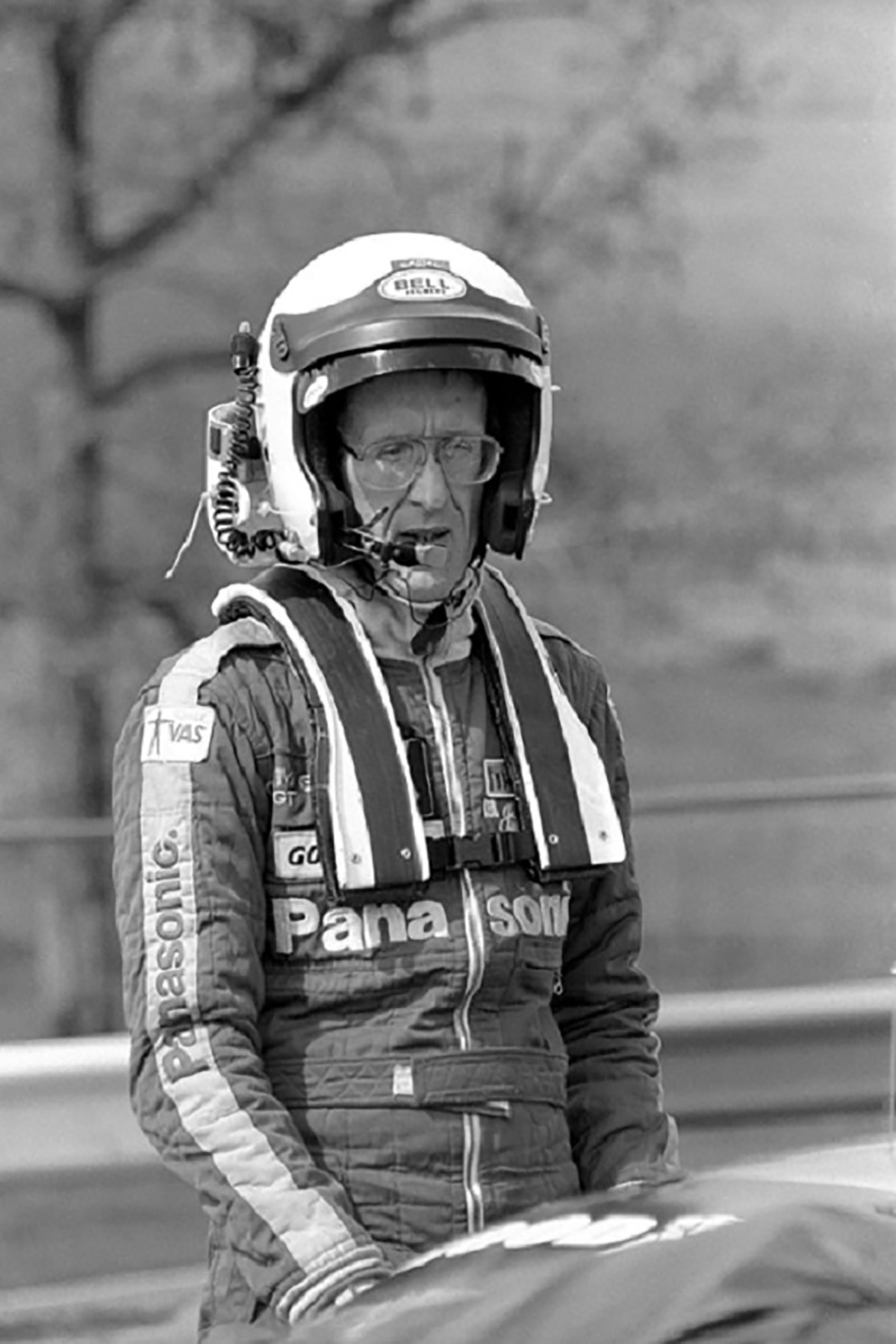

1989 March 31 | Friday: Jim Downing (63) Mazda driver tests a prototype of the HANS device in practice before the Nissan Camel Grand Prix International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) Camel GT event at Road Atlanta in Braselton, Georgia. Photo by David Allio

After the deaths of Adam Petty and Kenny Irwin from basal skull fractures earlier that year during two separate NASCAR events at the New Hampshire International Speedway, Helton was very interested in talking with Downing about motor racing’s first head and neck restraint. Since NASCAR closely controlled all aspects of its racing series, any safety device used by drivers had to have the sanctioning body’s approval.

Downing had met the future NASCAR president in the early 1980s while building Mazda RX-7 pace cars at his Downing/Atlanta race shop for the Atlanta International Raceway, where Helton was the general manager and in charge of securing the cars to fulfill a sponsorship deal financed by Mazda. Not long after that deal with Downing, Helton left his post at the Atlanta track to take a similar job at the giant oval in Talladega, Alabama, before moving to Daytona Beach as an employee at NASCAR’s Florida headquarters. Tall and broad with imposing eyes beneath a thick mane of dark hair, Helton had gradually worked his way up the NASCAR hierarchy.

“I knew Jim Downing from his racing days when he was the Mazda driver, when he was up in the wine country of Georgia and I was down in the moonshine country,” recalled Helton. “I knew Jim Downing as a racer. Atlanta Raceway had a deal one year with Mazda. We had Mazda RX-7 pace cars and they were souped-up by Downing. Bob Hubbard came along with that process of knowing Jim and in that time (after the driver deaths) we were getting more aggressive in talking with folks like that.”

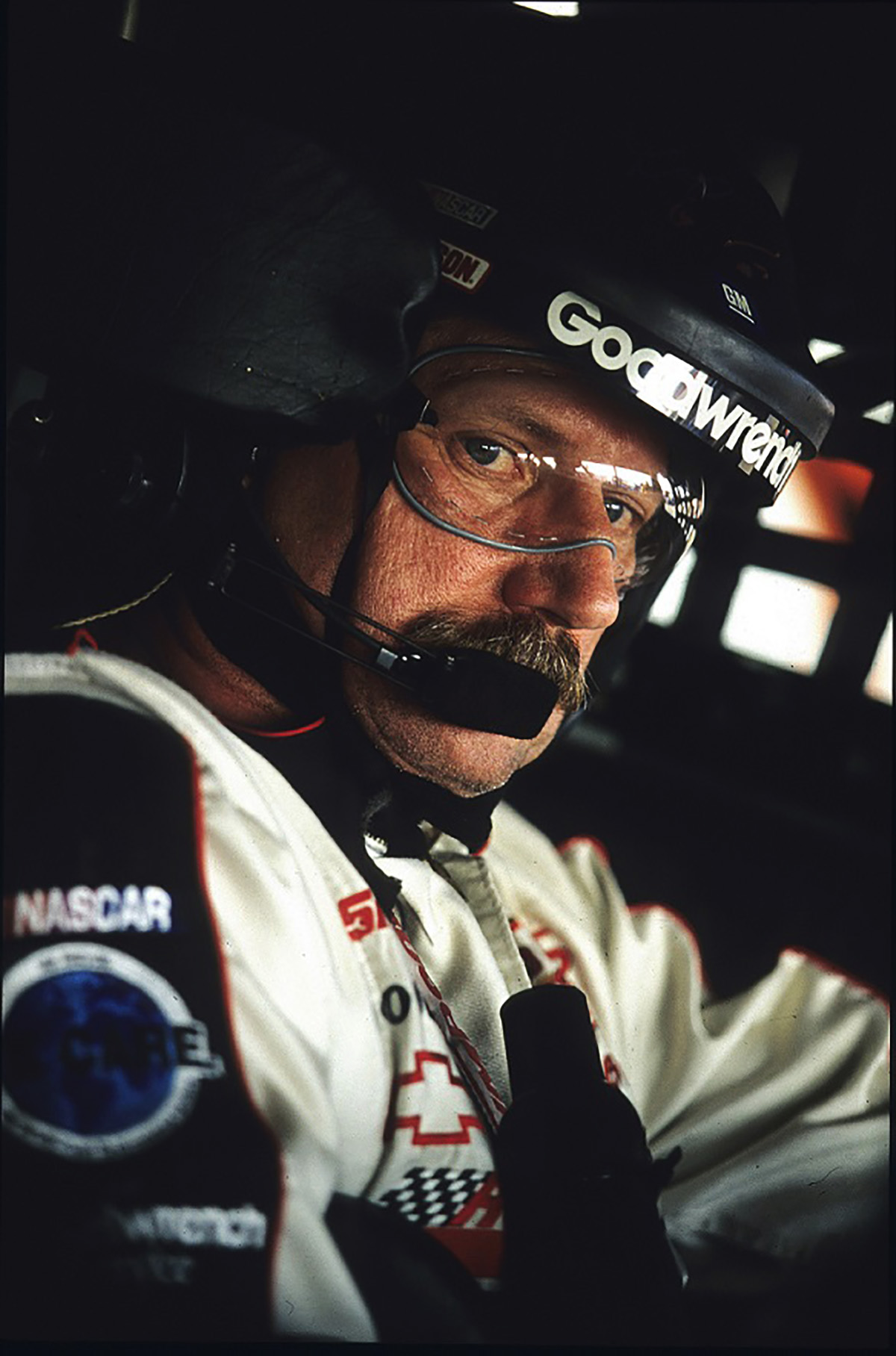

Earnhardt wanted nothing to do with the HANS Device at the Indy test. “Dale came through the door of the NASCAR hauler, just walked right in while I was talking to Mike about the HANS,” said Downing of his first meeting with the driver known as “The Intimidator.”

“They had a little desk in there and he threw his leg over the corner of it and kind of sat down. He looked at us with that bristly mustache and a grin as if to say, ‘What are you guys talking about?’ The message was pretty clear. He didn’t want to have anything to do with the HANS and didn’t want Mike listening to what I had to say. Earnhardt sitting there pretty much brought the discussion with Mike to an end.”

Twenty years prior to meeting Earnhardt, Downing’s own experience with a head injury resulted in a fortunate outcome—given the dangerous nature of his crash on a track in Canada in 1980. On a sweltering August day at the Mosport Park track near Toronto, Downing was sweating profusely while competing in the Molson 1000. Onboard a Mazda RX-7 entered by the Racing Beat factory team, the tall, slender Downing was running first in the GTU class with the other Racing Beat Mazda immediately behind him in second place. Its driver, John Morton, was looking for a way past.

The 10-turn Mosport track undulates around glacially carved hills. Because of the almost non-stop high speeds, it’s a thrilling place to watch a race. On this summer day, fans, many of them camping overnight in tents on the various overlooks, had come out to see the World Championship of Makes race sanctioned by the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). The race also paid points for the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) and the combined entry featured some of the world’s best sports car teams and drivers.

This included numerous Porsche 935 Turbos, relatively crude silhouette cars. These ill-handling tube-frame machines were wicked fast due to turbocharged engines producing gobs of torque that hit the drive train like a thunderstorm. They were driven by sports car stars such as Brian Redman and John Fitzpatrick and by moonlighting Indy car drivers Rick Mears, Danny Ongais and Johnny Rutherford. Twenty-year-old future star John Paul, Jr. was another of those behind the wheel of the Porsches. The fearless and fast German, Walter Rohrl, co-drove a Lancia Turbo in search of FIA points and renowned team owner Bob Tullius of Group 44 was competing in a Triumph TR-8 for British Leyland.

In IMSA’s standard endurance racing formula, the GTU class for cars with smaller engines consisted of Mazdas, Datsun 240Z’s and Porsche 911 Carreras. While they relied more on momentum and less on horsepower, the GTUs were scary to drive at Mosport, too, because of their nimble cornering speeds—–and the constant swarm of faster Porsche Turbos.

During this particular summer, the heat and humidity were not unusual for August. But to find more speed, the engineer at the Racing Beat factory team had closed off most of the airflow into the cockpit. Downing had worked his way into the graces of Mazda’s racing management due to his quickness, reliability and low-key confidence that fit in well with the Japanese. He intended to sustain his career momentum and decided not to protest the lack of air coming through the cockpit.

Already a championship contender aboard Mazda RX-3s in the RS series of IMSA for compact cars running on radial street tires, he was looking to advance to the big leagues of American sports car racing and into the GTU category where Mazda was a major player. But he lost so much perspiration during the race’s first hour in the muggy cockpit that he passed out behind the wheel while heading into Turn Two—–a fast, sweeping, left-hand corner.

For the first and only time in his career, the crash briefly knocked Downing unconscious. Events became fuzzy as he was taken to the track medical center. It was like a dream—tumult, and noise all around him, but everything distant and one step removed, the roar of the cars on the nearby track now a distant hum. The memory lingered after an overnight stay in the hospital.

Patrick Jacquemart puts his amazing turbo-powered Renault through its paces at Mid-Ohio in 1981. He would be killed in a testing accident in the same car at the same track a few weeks later. Photo: Peter Gloede

“I just got lucky and the car turned backward,” recalled Downing. “It was a concrete wall with a hill behind it. The impact cracked and broke the wall. The car was so bad, they left it in Canada after stripping a few pieces off of it.”

Downing realized a head-on crash could have been deadly. (Five years later, Manfred Winkelhock was killed by a head-on meeting with the wall in Turn 2 on board a Porsche 962C during a World Endurance Championship race.) Downing began to think about the number of head and neck injuries happening in racing at the time. Like so many racers, he shrugged off his crash as part of the business. Then, the following spring, Downing learned that a frontal impact by fellow GTU racer Patrick Jacquemart at the end of the back straight of the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course during a test was indeed fatal. The cause of death was a basal skull fracture.

Downing’s first reaction to his own near-miss typified the ambitious racer’s point of view, whether it was Formula 1, Indy cars, sports cars, stock cars or rallying. ‘It won’t happen to me again,’ he thought. But when Jacquemart’s crash occurred, the realization sunk in with Downing that it might have been his funeral. He then asked himself a once again: ‘Why can’t something be done about head injuries?’