Don Capps seen here with Quinn Beekwilder chatting about the roundtable at the 2024 Argetsinger Symposium

The roundtable discussion will explore the juxtaposition of motorsport history with more conventional and traditional forms of cultural history and cultural studies, that is, the history of motorsport (its cultural and social evolution) vs. motorsport history (its technical evolution, equipment, personalities, events, etc.).The 2024 book Speed Capital, by Brian Ingrassia, will be the basis for this roundtable discussion, exploring the relationship between motorsport history and the cultural and historical narrative.

Bio

Don Capps is the co-founder of the Argetsinger Symposium, along with the late Michael R. Argetsinger. He was a member of the SAH Board of Directors from 2014 to 2023, SAH President from 2021 to 2023, and is a member of the Historians Council of the IMRRC. Capps began following motor sports at an early age while attending races with his father at Lakewood Speedway in Atlanta. In addition to motor racing history, military history, and civil and military aviation history, have also been lifelong interests. A retired Army Colonel with over 30 years of service in North America, Europe, the Mideast, and Asia, Capps holds graduate degrees from the University of South Carolina and George Mason University, as well as being a graduate of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. He has taught history at both the high school and college levels, the latter being at The Citadel.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… here are some chapter markers to help guide you through the presentation.

- 00:00 Introduction to the Motorsport Round Table

- 00:30 Origins of the Motorsport History Symposium

- 01:43 Key Figures in Motorsport History

- 02:12 Significant Publications in Motorsport History

- 10:04 The Role of Public History in Motorsport

- 12:00 Introduction to Brian’s Book: Speed Capital

- 17:42 Brian’s Journey to Writing Speed Capital

- 22:06 Carl Fisher’s Impact on Motorsport and Beyond

- 30:23 Nostalgia and the Evolution of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway

- 39:13 Nostalgia and Cultural Connections

- 41:36 Indianapolis and the Auto Industry

- 42:44 The Shift to Spectacle and Sport

- 44:17 The Role of Speedways in American Culture

- 47:22 The Global Influence of American Speedways

- 50:14 The Evolution and Impact of Speedways

- 54:30 The Cultural Significance of Motorsport

- 59:34 Future Directions in Motorsport History

- 01:10:05 Closing Remarks and Reflections

Transcript

Don Capps: [00:00:00] In Washington’s Glen, uh, today, uh, it’s a lunchtime entertainment for Saturday. We are having a round table on the state of Motorsport history. Uh, we’ve gotten together a, a, a nice group, uh, but it’s very important to understand that we’ll talk a lot. But we have, we want you to know why we’re here in the first place.

About 10 years ago exactly. Uh, Amy Bass and, uh, the American, you know, the Journal of American History took, had an article on the, the cultural turn in sport history. Um, Mike Argen, Inger and I were very taken by that. We’d already been plotting and scheming to have something evolve from the center conversations that were going on.

And we decided that we will make it happen. And we [00:01:00] finally got support from the, uh, the governing council was, it was called the Board of Directors. And then unfortunately, Mike, uh, illness, uh, came back and before we could do anything, he passed away. We had decided, uh, to name it after his mom, gene Argen Singer, because she’s the person who made the international motor racing, uh, research center happen.

Believe me. Uh, having been one of those people that, uh, was tagged by Ms. Jean to be part of the crew, boom, she made it happen. So that’s why we’re here. We wanna talk about what the state of the, uh, Motorsport history is. Uh, the, the people I’ve got right now, I’m gonna talk, let’s start off with, with Markel.

He’s a, uh, professor of communications at, uh, Northwestern Michigan. College way up in Traverse City, Michigan. Uh, [00:02:00] fighting with Haggerty people every day over the insurance race, I’m sure. Uh, got his doctorate from, uh, Boling, uh, green State University. Who one of the cultural guys. Uh, this is one of the er books of the Academic Motorsport community.

This puppy came out, uh, in, in nine what, 1997. From Moonshine to Madison Avenue Culture. History of the NASCAR Winston Cub Series is a landmark. Uh, there had been a gap between any rural academic works on, uh, Motorsport. This one, I think opened a lot of doors to people. Uh, the, uh, bowling Green, uh, I’m trying to, I never get popular press.

Published it, which bless your hearts, because it, it really, it’s a great book. The, I [00:03:00] cannot push it hard enough. It really shook a lot of us up because wow, we can talk about this. We can do notes, we can do, we can, you know, we got enthused about it. There were others that followed that. Uh, another book that he is, uh, edited along with, uh, John Miller, uh, uh, in Longwood Uni, uh, in, uh, university in, uh, Farmville, Virginia is in a great anthology.

This is a, one of those books I, if, if there’s a Motorsport class. This is, this is one of the textbooks that you have. Oh, the, the authors are great. Um, it is just a, a great variety. And the academic approaches are just superb. One of our saviors when we started the Oregon Singer Symposium [00:04:00] was Paul Baxa. Uh, he fell out of the sky on us when we really needed somebody.

Uh, Paul is, uh, at Ave Maria University down, uh, in, in Florida Ave Maria, as a matter of fact, uh, it is a wonderful place if you ha if you get a chance and you’re in the area, if you go to Revs, you gotta go out to Ave Maria. It’s a beautiful setting. Absolutely. Tom Knight, his first book one I like a lot because it’s something I’m very interested in as well.

It’s called Roads and Ruins, a symbolic, uh, landscape of Fascist Rome. Uh, I’m a roadside out, uh, architecture guy, and this is super duper stuff. Uh, you, the, uh, Toronto University Press, um, published it, uh, and I, I really can’t say enough. It, it, it really kind of blew my mind. It’s what [00:05:00] 2010, I think, think it was when it came out, but now here’s the coup de grot, as they say.

Um,

motor sport and fascism living dangerously. We kind of saw this book come together over time, and here is what makes this book the darn good gun, whether it’s an Italian or in English. This is one of the very few works, scholarly or otherwise, that addresses the relationship between the fascist in Italy and sport in the form of motorsport.

It’s super duper, uh, I can’t say enough about it. It, it really is a unique work and I think that it’s gonna open doors for things there. There’s only one other book that I’m aware of, and I have to go right here to get it. That comes [00:06:00] close. And this is by, uh, one of my compatriots, uh, Al Detai. Uh, uh, fel and Hug, Kurt, uh, Rin Sport I National Socialist.

Uh, um, and it is a another, these are the only two books that address these topics in an academic scholarly manner. There are others out there. Uh. But these are the two that really dig in there and do the analysis and the research. So we’re very fortunate for that.

One of the things that, uh, I’m delighted is that, um, uh, Brandon Ian, who has produced is the book we’re gonna talk about right on, almost right off the bat. [00:07:00] Um. Uh, Mark’s gonna take up after I shut up. Uh, speed Capital Indianapolis Auto Racing and the making of Modern America. I’m a, I’m a sucker for anything, just the making of modern America.

I, I’ll be very truthful about that. That is, that is one of the things, particularly when Motorsport involved, uh, we talk about that. But he also has a great journal article. Um, the Journal of Motor of, uh, sport History nash. If you aren’t a member of nash, you need to seriously consider it. I’ve been one for god knows forever.

It seems, uh, in the spring, 2023 issued volume 50, number one, which I thought was pretty cool. Uh, he has, he, this is a topic that we here at the Argen Singer have visited in different, different way. It is annihilating, space Motorsport, and a quantification of movement. Very much involved [00:08:00] in line with some of the things we’ve done in the past.

And it, and it is a great article. It is super to read one of our, uh, former members of the, uh, community, uh, Scott Beman. He said, uh, now notice how, what I’m gonna say Rio Grand University and, uh, Royal Grand, uh, Ohio, um, NASCAR Nation, a history of stock car racing. The United States Super Book came out in 2010, and there’s, I think, mark, I think you’ll probably agree this is one of the really good ones.

It’s very, it hits it and it doesn’t pull punches about a lot of things. It is almost a, it is a companion in a certain, uh, way with real nascar. Uh, Dan Pierce’s book, Dan Pierce said, university of North Carolina, Asheville Super guy, uh, white Lightning in Fred Clay and Big Bill [00:09:00] France. This is, uh, university of North Carolina Press, and it is a very popular book.

Uh, both of these I, I think, appeared simultaneously at the same time even. And they do a great job of, uh, putting an academic, uh, aspect. The children, Americans, I can say uniquely since they do have it in Canada, um, American sport. But the way we do it, there’s a lot of other anthologies out there. Uh, there’s one at, um, uh, road does number of these things, history, motor sport, which is, uh.

Worth really looking into. And then there’s this big fat one. Uh, the history in politics and motor racing. It, it covers a lot of space and it’s, it’s a, a typical Powell grave Mc McMillan book, uh, worth, worth, worth Getting [00:10:00] Us it.

One of the other people that got me started, Pete Daniels used to be at the, uh, the national, um, museum, uh, his American history. Uh, I had the opportunity to actually talk with any, by the way, one of the things in the book he talked about in stock racing, but anybody who devotes space, the Sputnik Monroe is gotta be a good guy.

If you don’t know Sput Monroe, you are lost. Anyway, um, I.

The other person that, uh, I, I, I would like to have here, but, but, uh, it will be there. Uh, it will be in person. Uh, as we’re, you know, we’re recording this, uh, is uh, is a great friend of ours, a great friend of the, uh, the symposium, uh, Dr. Dan Simonon. [00:11:00] Dan was another one of those inspired by what Mark did, uh, his dissertation.

Uh, he did his, got his ate in the University of, uh, Florida, uh, which is a unique thing to do since nobody really knew what he was doing. So he got away with it. I love that. And he was the curator at the NASCAR Hall of Fame Museum in Charlotte, uh, for about a dozen years. He was one of those that got the shape of the.

The atmosphere. I think that’s the word I’m looking for. Um, public history is a piece of this that I think it’s overlooked. Um, and I think it’s important that that comes up. And, and I think that Dan and I will talk about that in person to, to a degree. But anyway, I’ve talked enough and I hope everybody now got their box lunches and sitting there and, and, and ready to enjoy it.[00:12:00]

At this point, uh, I will toss it over to the esteemed, uh, Dr. Uh, Mark Howell to introduce and talk and talk with Brian, uh, and about its book because we are really excited about this thing. Mark.

Mark Howell: Thank you, Don. And, uh, hello everyone. Uh, wish I could be there in person, but, uh, uh, we’ve had a, a. A bit of a tightening of the purse strings of professional travel funding at my institution.

So, uh, I will be coming to you and I think if this is at lunchtime on Saturday, you would’ve just heard me complete my presentation, uh, first thing on Saturday morning. But, um, uh, it’s, it’s an honor to be here with Brian and with Paul and with Don as always, uh, to talk about, uh, what is, uh, a, a most fascinating look at, I wanna say [00:13:00] automobile history, but I also want to say motor sports history.

I also wanna say regionalism. I wanna say, um, uh, American culture, uh, because what Brian has done with speed capital is he has created this truly purely interdisciplinary look at something that to most people, they only have. Maybe a recollection of Indianapolis through what they see in the sports pages.

Um, Don as you were saying, you know, so, so much motor sports history came through journalism and came through people who wrote about racing as reporting on the event or telling the stories of the people who built the cars, who drove the cars. They talked about those particulars. But what Brian has done has is, is he has branched out and sort of taken us from that sort of microscopic look at [00:14:00] Indianapolis as a racetrack and taken us far afield to look at how Indianapolis came to be, not just the Speedway, but how.

The community came to be how this little village along wagon trails in rural, uh, frontier, Indiana, uh, turned into the commercial and political center that it did, uh, what it meant to the development of the Midwest, and then ultimately how four very enterprising businessmen with a vision and with, um, some property at their disposal ended up creating what is arguably the most iconic and most famous use of space for sport in the entire world.

Everyone everywhere knows Indianapolis. Even if you’re not a race fan, you know the Indianapolis 500, you know, the [00:15:00] Indianapolis Motor Speedway. And so that’s where Brian’s book I think has really. Sort of reinvented this idea of what we as historians, and most importantly as academic historians can bring to a subject like motorsports.

It doesn’t just have to be the cars, the tires, the drivers, the mechanics, the events. It can be this broader perspective on the communities, the founders, the fans, you know, like Scott does. And, and like Dan did, you know, with their books on nascar, looking at sort of the culture, looking at the people who made the sport what it is, and then looking at the people who are sustaining the sport.

Uh, that idea that, um, there’s more to motor sports history than just motor sports. And so that’s. That’s what attracted me to, uh, [00:16:00] to Brian’s book. That’s what, that’s what thrilled me when I was reading it. I know it sounds cliche, but the idea of, uh, I couldn’t put it down. That’s, that’s exactly not, not many books have that kind of effect on a jaded old historian like me.

Um, but Brian’s book, I truly could not put it down because every page as, as, as we were saying about, you know, the, the interdisciplinary nature of it, um, every page brought something new to the study, brought something new to the discussion, and those twists and turns that ultimately lead to the most famous racetrack on the planet and what that track means.

Not just in terms of competitive nature, but in terms of human nature and in terms of, of popular culture and American culture and global culture. This book really [00:17:00] hits each and every one of those highlights. And so, um, Brian, it’s, it’s a pleasure to have you here with us. It’s, it’s, it’s an honor to have you here, uh, and, um, uh, and, and we, we hope that we can have a really good discussion here about your work and, and what it means to not only the Motorsports community, but to that larger academic, uh, his history with the capital H community.

Um, so yeah, it’s, uh, let’s go ahead and talk, talk Indianapolis.

Brian Ingrassia: Thanks for those kind words. I appreciate it.

Mark Howell: Brian, let’s, I’m, I’m fascinated about how your, your previous book was on college football, uh, which, I’m sorry to say I haven’t read yet. After, after reading Speed Capital, I, now I’ve, that’s on my list of books to grab. [00:18:00] What was it about Indianapolis that prompted you to take on this project?

Brian Ingrassia: I have a story I, I like to tell, and I probably told it too many times, but what happened is, um, I, I was off doing dissertation research in 2005.

In 2006 I was, I spent some time in the San Francisco Bay area, spent some time in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Spent some time in Boston and, uh, in the process as I was researching about college football, college football stadiums, things like that, some of the things that show up in my first book, um, I, I really decided, and it’s funny ’cause I, I grew up in a, a small town, kind of small city in central Illinois.

We never went to cities as I was a, when I was a kid, I started realizing that I really liked cities. Um, and especially Boston. I liked the public transportation and just kind of the, the energy of the city. And I got back to Champaign, Illinois where I was doing my dissertation, where I was doing my PhD, and I said, man, I kind of miss cities, you know, and, and the, the, the easier thing for me to have [00:19:00] done or the, the logical thing for me to have done would be to drive up to Chicago or take the train up to Chicago and do Chicago stuff.

But I realized Indianapolis was a little bit closer to Champaign, Illinois and it was a little easier to drive to and park your car. And so I just, I, I would periodically go over to Indianapolis, do Indianapolis kind of stuff. And one time I was there in the summer of 2007, so this is like. 17 plus years ago, um, I was, I, I, I drove past the Speedway.

’cause coming in from, on I 74, I used to go right past the Speedway, which I had seen before. It wasn’t the first time I’d seen it, and I realized, oh, I’m writing this, this chapter all about football stadiums. And I don’t know how this 250,000 seat stadium essentially ended up here in Indianapolis. And I was like, I, I, I wish I knew more about that.

And then it was that day I realized that the, the Speedway is not in Indianapolis proper. It’s in a place called Speedway, which used to be Speedway City, Indiana. I’m sure some of you are, are familiar with that. And I, that day I said, you know, I, I just need to go read the best [00:20:00] thing that’s ever been written.

Best academic thing that’s ever been written about Speedway City, Indiana. I went and looked and nobody had done it. I said, oh, that’s interesting. Now I need to go read the best thing that’s ever been written, academic thing that’s ever been written about the Indianapolis Motor Speedway went to find it and I said, nobody’s done this.

And I just kind of started doing, you know, the preliminary, like going down the rabbit holes on, on Wikipedia and whatever about like who built this thing and why they did it. And I started learning about Carl Graham Fisher, which again, I’m sure many of you are familiar with Carl Fisher, the guy who essentially built the speedway among other things.

And I said, there’s a book here, there’s a really interesting book here. And it’s, what I started thinking about was how the work that’s been done. I pretty quickly figured out the work that’s been done about Carl Fisher. It’s mostly about Miami Beach. He’s known from Miami Beach. His papers are in at the, uh, Miami History Center there at the Dade County Public Library.

And I realized, oh, everybody focuses so much on Carl Fisher and Miami Beach that they’re missing out on. What is I, I would like to say is the center of his automotive [00:21:00] empire. And that’s Indianapolis. That’s the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. And I said, there’s a story here about this guy who builds a racetrack build, build on head headlight money, right headlamps, sells doubt to Union Carbide, makes the money, and then builds a racetrack, and then also builds the highways and builds Miami Beach, Florida, and builds, you know, tries to build Montauk, uh, point Long Island.

And then, you know, his, his empire collapses in the 1930s. And that’s, that’s a long-winded answer to say that’s really what got me going was learning about Speedway City, Indiana. Um, and Carl Fisher, the guy who kind of pulls, he’s, he’s the central node in, like I said, this kind of automotive empire of the early 20th century.

Mark Howell: And that’s, and you know, and, and that’s welcome to the club. That is such, that is such a, an, an, an origin story I think that we all in, in our, in, in our own careers have experienced, Hey, what’s that? And then you fall down, as you say, the rabbit hole of research and you start [00:22:00] finding all of these loose ends, but then you find that none of those loose ends have been tied up by anybody.

And suddenly there’s a story there to tell, you know, and, uh, you know, and, and like you say, you know, Carl Fisher is, is, you know, obviously the, the, the name that goes with the speedway, but that idea of him to branch away from the motor sports, the idea of him being someone who manipulated space and nature to create, not just the Speedway, but what you say about his creation of Miami Beach.

You know, and, you know, filling in, you know, take, taking land and making islands and, and reshaping the, the natural landscape to make it an entertainment location, which he, which he did with the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, you could argue that that’s an entertainment location. Um, and, uh, and, and that idea of [00:23:00] how much more he meant and how much more his partners meant in terms of, as you say, the, you know, the, the creation of highways and roads, the, the, the, the idea that government gravitates, you know, and, and business gravitates to Indianapolis.

Um, yeah, it’s, uh, it, it’s a, it’s a marvelous story. Yeah. As once again, welcome to the club.

Brian Ingrassia: You know, one of the things I think that’s really fascinating about Fisher. Is, um, you know, we, again, we talk so much about how he builds Miami Beach from a sandbar into, into Miami Beach. Um, I, I’m, I’m convinced that he learns how to manipulate space and how to build things through the speedway.

That’s really his first experience with reshaping land, um, in, in this case for a, a spectator facility, right. A Motorsport facility. And he takes, I think, some of the things he learns in Indianapolis, and then he takes it down to Miami Beach and, and builds Miami Beach into this kind of tourist center, right.

That you, [00:24:00] you pretty much have to drive there, um, in order to get there. Um, and, and something occurred to me as I was working on, probably took 12 years or so to this, occurred to me that we always talk about Henry Ford. Henry Ford’s, the guy that taught Americans to love cars. And there’s probably some truth to that, right?

But Henry Ford was the guy who, he mastered the production of automobiles. And I think that Carl Fisher, in some ways, he’s almost as important as Henry Ford, but he taught. He taught us about consuming automobiles, not just buying them and driving them, but about how to enjoy them. Right. You know, you need, if, if you’re gonna enjoy your automobiles, you need roads, you need places to drive to.

You need, I mean, a spectacle. And he created that in a way that Henry Ford, you know, of course early on in his career, Henry Ford did a little bit of auto racing, but he was always the guy who was like, if he gets money, he’s gonna plow it back into his factory. If Carl Fisher gets money, he’s gonna build a fun place, or he’s gonna build an auto racing, you know, uh, uh, Speedway or something.

And so I think that we need [00:25:00] to talk, you know, I like to say Carl Fisher’s as important as Henry Ford. He’s probably not, but we need to talk about Carl Fisher as somebody kind of on an, an equal plane in a lot of ways to Henry Ford in terms of teaching Americans and teaching the world how to consume automobiles.

Don Capps: Yeah. One of the things, uh, Brian, you mentioned, uh, and I think Mark pretty well nailed it as well, is the fact that. You talked about, you started looking and I had mentioned, you know, to you privately that there’s this linear meters of books on Indianapolis, the 500, the Speedway, whatever. But when you start peeling back then onion Yeah.

Mean God, it may be kilometers for all I know. You, you find not much there of substance. That’s what made [00:26:00] this to me fascinating because you did what some of us didn’t have the sense to do. You pull that together and I like that. The, and and you’re, I think you’re hitting on that the whole business with, um, uh, with Fisher makes sense and it’s always pulse with me.

I, I got in some Indiana, you know, in Indiana, uh, Indiana roots and it’s like. How did this get here type of deal. And it is, people forget it was a, a major locale in, in that, in that time period is, it may have been passed by, but it is good. So, so yeah, that to me is very fascinating and how you did that out from there, you know, where would you have us look now, based upon what you’re doing?

Where do we need to go next with speed capital?

Brian Ingrassia: That’s a, that’s a good question. Um, and I’m gonna go back to something you said a minute ago about the, you know, the [00:27:00] meat errors, the, the kilometers worth of books. I, I hate to admit it, I, I didn’t read all those before I wrote my book. I’ve read some of them, you know, in the process.

And I think when I have read some of those books about Indianapolis, they’re so focused on the cars and the races that I, it. I’m not saying it wouldn’t have helped me to read more of those, but, but at a certain point it was like, I want to break out of that mold. Right. And one of the things like, I realized, I mean, what’s obviously, what’s the nickname for the, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway?

It’s the Brickyard. Right. And what, what you have to realize, I think if you look at a, a track like the Speedway, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, if you just look at the cars, you’re only looking at roughly half of the technology. Right. Because there’s a lot of other technology that goes into making a speedway into a really, really interesting place.

It’s the automobiles. It’s the tires, but it’s also things like the bricks that they put down on the track or whatever the pavement is on the track. [00:28:00] It’s the lights surrounding it so that you can have events at night. Um, you know, early on in the, the speedway’s history there, the first events were balloon contests.

They were aviation contests with airplanes. And some people, some good historians who have written about that just kind of dismiss those things. They go, well, that was just a publicity stunt. That was just the way Carl Fisher was trying to get people interested in his auto races. And I, I looked at it, I said, no, I don’t think that’s what he’s doing at all.

I think he’s creating the speedways of place to demonstrate all these, what I call space annihilating, what they called space annihilating technologies. And if you just act like those are publicity stunts and you kinda like forget about them and you just focus on the cars, you’re missing the idea that at least before World War I, up to about 1917 or 1918, the Speedway is probably.

I won’t say it’s as much about aviation as it is about auto automobiles, but it’s like maybe a third about aviation and it’s about these technologies of getting people more quickly from place to place, um, in the modern era. And that’s what, that’s one of the things Modernity’s all about is using technology, I think to limit the structures of time [00:29:00] and place and Fisher’s kind of a master at that, and I think that the Speedway is a good representation of, of those changes happening in the early 20th century.

Paul Baxa: Yeah. Go ahead. Go ahead Paul. You sure? Okay. Sorry. Um, yeah, Brian, uh, once again, just a great book, very rich, fertile and ideas. It’s amazing. Um, but yeah, the connection between, um, auto racing and aviation, uh, I think is something you bring out really well. And, uh, you know, that’s where Rickenbacker then kind of comes in in the twenties and so I thought you did that really well.

But, um, the thing about the competition history. Uh, you do bring that in. And one thing I really love about your book is you talk about the context and all these different, um, you know, factors like urban planning and aviation and, and everything else, but you always come back to the races and you always have a, you know, a little section in each chapter on, you know, 1916, this is what happened, 19 seven, uh, no, 19 21, 22.[00:30:00]

And I really liked that. So I think, um, you know, ’cause that’s one of the big challenges with writing sports history is, um, you don’t want to be too journalistic. You don’t want to get into just the anecdotal and the, you know, what happened on the field or on the track, but you can’t really ignore that either.

I mean, it’s, it is important. And, um, so the way you weave the two together, I thought was, was outstanding. Um, but one, one other thing that I wanted to say, what I really liked about your book is how you trace the nostalgic impulse. Beginning in the thirties that, you know, there’s a point in the thirties where the Indie 500 or the promoters start to look back on the event itself.

I just kind of meta Ahi history, if you will, of, of the event itself. And they start to promote their, the history. And I thought that was really brilliantly done. So, um, yeah, I, I, I wrote a review of your book as well, so it’ll, it’ll be out soon and it’s, it’s a glowing review. But, but yeah. Those [00:31:00] are some of the things that I really liked about it.

Brian Ingrassia: Yeah. And, and if I can respond to, to a couple of those things. Um, yeah. So, uh, trying to remember the first thing you were saying before you went to aviation. It’s the actual racing. Um, you know, I, my original thought when I was writing the book is it, it was gonna be much more about Speedway City and urban Farming mm-hmm.

And

Brian Ingrassia: those kinds of things. And it was gonna be less, much less chronological.

And

Brian Ingrassia: as I started working, I started saying, you know, if there haven’t been a lot of academic works on auto racing, I mean, I know there’s some NASCAR stuff, right? And, and some other things I’m not, I’ve actually learned about some of them from Don.

I, I need to go reread or read some of these. Um, I said, you know, at a certain point I think we just need to tell, I need to tell the story of the races, you know, and go through newspaper accounts and, and as best as I can, construct what happened at those races. And, and it’s, it was kind of fun because you start to see how, you know how much faster things are getting, you know, when, when it’s, we’re talking a, you know, 130 mile per hour lap, uh, a race, [00:32:00] uh, speed, I guess a race as opposed to like an 80 mile an hour, uh, race, that, that’s a huge difference.

And, and we see those things happening and each race kind of, people talk about it in different ways and that changes over time. But the, the nostalgia thing, again, that’s something that wasn’t supposed to be in the book. I originally thought I was gonna end this maybe sometime in the post World War I, period, 1920s.

Um, my first book more attended around 19 or 29 or so, and then I pushed it a little bit later and what happened was, it was one of those weird serendipity moments where a few years ago I was at an estate sale, this is probably before the pandemic. I was at an estate sale in Amarillo, Texas, big house. Uh, apparently a doctor at the local VA hospital.

And they had like an entire, uh, a very complete run of Sports Illustrated from like the 1950s to the 1970s. It was like 20 or 25 years of Sports Illustrated. And I spent probably 45 minutes just going through ’em. And they were two bucks a piece or something. And one of the ones I bought was, it [00:33:00] had Eddie Matthews, you know, the famous Atlanta Braves slugger on the cover.

And I said, well, my uncle was a, he was a, sorry, not Atlanta Braves. Milwaukee Braves. He was a Milwaukee Braves fan. My uncle was. And I said, I’ll buy him this copy of Sports Illustrated, um, and he’ll enjoy it from like 1957 or something like that. And I took it home and I got looking at it and I go, oh.

There’s part one of a two part series about the speedway and about the new owner, Tony Holman. And as I got reading it, and they’re talking about the museum and how the museum’s getting built, the original one gets built in the fifties, the the present one built in the seventies around the time of the bicentennial, which of course is a important time for museums.

And I started reading, I said, oh, this is where the book needs to end. It needs to end with the building of the museum in the 1950s. And kind of how, you know, people are looking back with nostalgia to this kind of gold sports in the twenties. And then once I kind of figured that out, then I start reading all the stuff in the thirties and I said, oh, the nostalgia’s there before they ever build the museum.

Yeah. It, it even starts, I would say, a little bit [00:34:00] after World War I, but you can really feel it coming into play in the 1930s, uh, during the Great Depression. Mm-hmm. That, you know, the speedway’s been around for about 20, 20 years or so. It survived World War I, it survived. Stock market crash, and now people are starting to look back at it as this thing that’s been there.

It’s been around. And, and that’s also right about the same time that, um, the Baseball Hall of Fame is getting started in the 1930s. It is this kind of, the 1930s is this time period where ’cause of the depression, people looking forward to the future, they’re looking, they’re anticipating the future, but they’re also looking back kind of fondly to the past before modernity collapsed essentially in the 1930s.

And, and I think the Speedway is just such a good illustration of how that, how that develops. It’s not the only sport where it happens, but it’s a more important one I think, for understanding. And,

Mark Howell: and that’s, and that’s where your book really, you know, fits our overall sort of scope of, of automobile history and motor sports history.

Because so much of motor sports is rooted in some form of nostalgia. [00:35:00] We remember those great old drivers and those great old car builders, and we remember the famous races and we can all harken back to where we were when this event happened or what got us interested in a particular kind of motor sport.

You know, so much of studying, racing, just like history itself is, is really based on that, that sort of fascination with nostalgia. You know, remember when, and, and racing really sort of prides itself in that because you can look at an automobile from the 19 teens, the 1920s that raced at Indianapolis. You can go and actually see one, uh, you can actually go and see, you can go to the NASCAR Hall of Fame and see a stock car that competed on the beach at Daytona in the mid 1950s.

It’s, it’s, that’s it. It’s there. And it’s not just that nostalgia, but. There’s the artifact [00:36:00] right there. You can see it. And, and even if you had to, you could go over and touch it, you know? And, and that’s that. And, and again, to, to dovetail on, on what Paul said. Yeah. That idea of at some point we start sort of hearkening back.

Mm-hmm. And you know, that idea of, you know, who, you know, who was the first two time winner, who was the first three time winner, you know, who was the first one to break a hundred miles an hour? And, and you just start kind of swimming in all of that fascinating data that ultimately throws you back to that idea of this is, this is, this is our connection.

Mm-hmm. To that history. This, this is where we actually become part of it.

Paul Baxa: Right. And it’s an interesting tension. Paul, something. Go ahead. Go ahead Paul. Sorry Don. Uh, it’s an interesting tension too, ’cause Motorsport is about, you know, progress. You know, as Brian’s book shows, right? Every year there’s an increase in speed.

So it’s, it’s a, it’s a forward looking sport, but [00:37:00] yet you have this draw to the, you know, to the past as well. And there’s always a tension, I think, in Motorsport between those two things. So,

Brian Ingrassia: and, and I would say by the time they actually create the museum, or, or not long after they create the museum in 1950s, one of the things I say in the book is that a a, an a a race car is pretty much, it’s a historic relic.

Yeah.

Brian Ingrassia: A year or two, you know, uh, that, that’s not necessarily the case in 1909. But by the 1960s, I mean, as soon as you, you run these cars there, the, the technology has already passed it by. And I think that’s one of the things that’s so, you know, that’s so interesting about, about Motorsport nostalgia is that this technology is moving so quickly.

It does almost kind of so quickly turn the recent past into, into the past.

Don Capps: Yeah. And, and, and, and one of the things that Paul hit funny, how Great Mind thing alike here. Thank you Paul. Uh, with that whole business, the nostalgia of something that I kept seeing here, there in yonder [00:38:00] was Indianapolis was an interesting aspect of Americana in that it is the only race after the teens that the Europeans even basically knew existed well into the sixties.

Um, I mean, it took a while for the US Brom free for instance, but you know, but Indianapolis has this nostalgia for when the French came over that, you know, in 13 and 14 and all that, and then you have. Indianapolis adapting the inter, you know, formula international for time. And then in 38 it, the Grand Prix didn’t have Indianapolis.

It is, it runs to Grand Prix formula. I mean, Italian, oh no, you, you, you have [00:39:00] a Maserati. And, and by the way, I’m a Maserati guy, uh, comes over and they do success. Very successful because someone was very clever and said, I think this can happen. We can make this. But that goes back to something that Paul hit.

There was this nostalgia for this international connection that got lost. And I think you kind of get on that. And, and, and I think that’s part of what this whole cultural thing that we, we, we get involved with is that there was a culture that had. Created in Indianapolis that always had this outward reach to Europe.

I mean, I just find it fascinating because, you know, even when you have a, um, reduction based formula, uh, from what, 30 to 37, you still have a [00:40:00] European interest. Not necessarily great, but people are writing about it, people are looking at it. The Italians took it very seriously. I know that, uh, I mean, that’s one of the reasons that, uh, they were able to do that.

But yeah. And that goes back to, to again, Brian, this holistic cultural approach that you took it all, it, it, as Mark pointed out, all these little dots start connecting. That nostalgia, that, that, you know, the two of you have talked about, that becomes an important part of this, the, the remembrance, if you will, of, of that.

So that, that to me, you know, and, and this conversation has really kind of sharpens some of my ideas about it. That that’s really the sort of book I, every time I pick it up, I start flipping through it or find something like, oh, [00:41:00] where did that come from? You know, I thought, I,

Brian Ingrassia: I, I’m reading the words differently.

That, that’s quite a compliment. I mean, I, I, I just want people to read it. So if you pick it up and read it, look at it again, that, that’s, um, I’ve only

Don Capps: read it four times. So, you know,

Brian Ingrassia: um, I think what you’re saying about the international dynamic is really interesting because that’s something that’s in there, but it wasn’t.

Really stressed, but I, you’re absolutely right, um, depending on where we’re at in time, right? pre-World War I is different from say the 1920s and thirties, but I think there’s also kind of a regional nostalgia that comes into play there. You know, you were saying earlier, the Indianapolis is an early manufacturing center for automobiles, certainly before 1932 or 33 before the Great Depression, Indianapolis, it’s not quite Detroit, but they’re making a lot of cars there.

And then the depression pretty much kills off Indianapolis auto industry other than maybe some parts manufacturing in central Indiana. And there’s probably reasons for that. But in a weird way, the [00:42:00] death of the auto industry long term is probably a good thing for Indianapolis because if you compare it to Detroit, what happens to Detroit, right?

I mean, Detroit it, it is the giant of American auto manufacturing. And at a certain point in the 1970s and eighties. That more or less kills off Detroit. Right? Uh, with all due respect to, to people who, who live in Detroit and love Detroit. I know there’s people who, who, who love it as a city, but it, it gets so focused on producing automobiles, the Henry Ford, um, uh, uh, production and so forth that, um, that that’s all it can do.

And what happens at a certain point is Indianapolis isn’t producing automobiles by and large after the 1930s. And instead they’re focused on the spectacle and they get focused on the nostalgia, and they get focused on kind of the symbolism of automobiles as much as the actual production of automobiles.

And at a certain point, what seems to me like happens is Indianapolis, it it, it takes kind of a postmodern turn [00:43:00] at a relatively early date, right? Where instead of continuing, focusing, producing the cars, we’re gonna produce a spectacle that’s about cars, that’s going to build the mystique of this place.

To the point where by like the 1970s, Indianapolis is making a conscious decision. We are going to, part of our focus in terms of building the economy of this place, it’s gonna be about sport, it’s going to be about professional sport, it’s gonna be about amateur sport. And you look at Indianapolis history in terms of sport.

Yeah. They’ve got, you know, they’ve got, um, I mean now they have a couple of, of big league teams in terms of football and basketball. Um, but they, um, what they do the PanAm games in 1987, the NCAA has its headquarters there now. Um, it’s a speedway of course goes back, uh, far. And I think that Indianapolis in some ways kind of get in more so than most Midwestern cities.

It kind of gets out ahead of that change in the economy, that it’s no longer just about producing things, but it’s also about producing, um, I don’t know, me, [00:44:00] media spectacle and, and an automotive spectacle. I,

Don Capps: I hope that that’s a good, that’s a very good point. Yeah. Um, because other than baseball. Uh, it had a triple A team there forever and ever and ever.

The sports explosion seems to be tied very directly to the ability of all these people coming in with their different sports to the speedway and the expertise that has been built up over time and so forth. I’m gonna read something that, there’s a book that had bothered me for ever since it came out.

Uh, Stephen Reese is one of the gods in Nash. Got it. Uh, I’ve talked to Steven a couple times that even hit him on this one.

It’s in a, um, a series called the [00:45:00] American History Series. It’s Sport Industrial America, 1850 to 1920. One of the few automobile related things that gets mentioned is Indianapolis, and on page 44 it says, car racing remained a significant sport in the 1920s, but the automobile’s primary role in sport was primarily transporting fan to ball games and golfers to the length.

I’ve never forgiven even for that is accurate. That may be, uh, but that I think sums up why I was so taken with your book because it’s, I wouldn’t say a antithesis of that, but it plays off that very much so because without the automobile. There was no Speedway [00:46:00]

Brian Ingrassia: s Steve and I had a, a bit of an exchange one, and, uh, he was editing something I, I had written for something.

He was, he was editing a, a volume of some sort. And I said something about the Speedway was a suburban venue. And he is like, no, it’s in the city. And I was like, not in 1909, it wasn’t, it’s four miles from downtown. I mean, today it’s kind of surrounded by the city, but it wasn’t when they built it. And I think what’s interesting what you just said that about it being kind of people driving to sports, I think that I, I really believe that like the speedway is like the prototypical suburban stadium.

The place that you drive to, to see sport. Like you don’t really have that before 1909. And what is it? It’s a place, not just you drive there and you watch sport. It’s not to watch baseball or football. You drive there to watch sport of the technology that took you to the place. And I think that’s just, that’s so.

Why haven’t we talked about that? Why haven’t all the sport historians who talk about stadiums and suburbanization of stadiums, people like Steve Reese, why don’t they [00:47:00] talk about the fact that really the first place where you can do that is an automotive speedway built like five years, I can’t remember exactly the year of the Model T, but it’s like the year after the Model t’s introduced or something.

Right? Five years is I, I’m thinking of the, the first automobile in, in my city of Amarillo, Texas shows up in 1904, you know, and then within five years you’ve got this, you’ve got this speedway in Indianapolis. And then going back to something Paul said earlier, um, you know, kind of where do we go from here?

I, I would say one of the things that surprised me the most when I was doing the research was like every city in America had a speedway. There’s like a moment, not every city, but a lot of cities between like 1910 and like mm-hmm. 1917, like right before World War I, I. Omaha, Des Moines, um, Amarillo, Texas, where I live, had a couple of different speedways for a couple years.

Don Capps: Brooklyn. Brooklyn, that’s you’re talking my home here. Okay. And I,

Brian Ingrassia: I think that in, in some ways, [00:48:00] the success of the automobile in the 1920s sort of kills off Speedway racing, except it just a couple places, right? Like Indianapolis. And I think that, I think that by one of the things that occurred to me as I was, as I was researching writing the book, I said, we need to know a lot more about these kind of little speedways that disappear after five or 10 years.

Why is there this huge boom in the 19 teens? And then it kind of disappears. And I think that’s part of the reason why nostalgia is so important for Indianapolis, is because there’s, there’s nobody else hardly in the United States that’s doing this until you, of course, you get NASCAR and midget car racing and some of these other types of, you know, later Formula One, I think is coming to the United States.

I admit, I, I don’t know. I can’t tell you all the years that these things happen, but. Indianapolis is kind of the place that’s left. You know, they’re left standing and there’s a couple moments where the speedway almost got turned into something else. It almost, it’s an airport. It almost becomes a suburban housing, um, uh, development a couple times.

There’s several times where they [00:49:00] could have taken that land, divested it, turned it into something else. And basically what happens is by the 1940s, by the time Tony Holman buys it, he realizes this place is more valuable as a sporting center than as a housing development or, or that as an airport. The land, again, because of all the tradition and the races there is, it’s not just nostalgia, it’s this sense of like, there is value in the sporting stories that have been made here for the last 20 years or so.

So that’s my rambling way of saying I do hope that we start to learn more about these, these other speedways. ’cause I had to kind of piece it together from newspapers and like some websites that are out, out there to try to figure out. What was going on at Omaha and these other places, and there’s all these tracks that almost get built, and you can find newspapers where they’re gonna build one at Louisville, they’re gonna build one at Philadelphia, um, Providence, Rhode Island.

And some of them get built, you know, there’s one down in Miami, Florida that gets destroyed in the hurricane of 1926. What’s that? [00:50:00] Carl Fish. Carl Fisher built that track, didn’t he?

Paul Baxa: The board track

in Miami, Oakland.

Mark Howell: Yeah. It, it, it, it, there’s a lot that don’t get built, so, but, you know, but you’re, you know, that we talk about the, the role of the speedway.

That’s where the speedway became sort of a, a, a symbol of the future because so many communities looked to the success of Indianapolis and looked to the spectacle. And that’s where a lot of those chamber of commerce is, I think started saying, Hey, let’s build one of those here. And you know, and then you get into the, you know, and, and, and you know, you know, we just mentioned, uh, I think Paul, you just said, you know, the board tracks, you know, they raised the spectacle of motor racing to an nth degree because they were high banked.

They were smooth, they were incredibly dangerous. They were also incredibly delicate because, you know, one spark could burn the place to the ground or a hurricane [00:51:00] could blow it away. But that idea that, you know, Indianapolis had the speedway and it had the bricks and it had its own kind of thing. But then people saying, well, we could do that too, but just a little different, you know, and, you know, building, you know, sheep’s Head Bay and Altoona and places like that, where it’s the idea of what they saw in Indianapolis, but they wanted to kind of put their own kind of spin on it.

Unfortunately for a lot of, you know, yeah, you had dirt tracks and things, but for a lot of the big spectacles, you had those board tracks that were, you know, just, uh,

Don Capps: ephemeral.

Mark Howell: A complete yeah. Just a completely different animal altogether. And, um, they didn’t last. Indianapolis has weathered a whole lot of storms and is still, is, is still successful.

Uh, I don’t know of many airports where you [00:52:00] go, you walk through the terminal and you see race cars. Yeah. You

Don Capps: know, I guess Parksville International was built on the Atlanta, uh, Speedway. Two things. One, mark knows this. Harold Brasington said the Darlington Speedway was influenced directly by what he saw in Indianapolis, and also thrown this over in Paul’s lap.

If we take that dot and push it across the water. You have Tripoli, you have manza, you have a, you know, the ve ring. You, you have uh, re you have all these European little speed palaces as well, capitals of speed. And so there is, it’s not just an American phenomenon, although I think it’s been overlooked.

If you [00:53:00] correctly point out, Brian, to the point where I, I, 25 years ago, I knew a little bit and I, and, and I spent 25 years digging into what you’re, you, you know, into those things. And I still find stuff all the time when I go through a motor age or an honorable bill. Like, where does that comes from? And, and so forth.

But, but I, again, I think Paul, that’s one of the things that, that, again, fascinating ’cause that architecture, it’s represents an ideology in many instances. Uh, although with the Berg Ring was added afterwards, uh, it was built before the National Socialist. But Triple E is another example that is very much influenced, I would say, by Indianapolis, to be perfectly honest.

When you take a look at ’em, and as Brian has correctly [00:54:00] pointed out, when you start looking at these integral pieces, suddenly you are finding as historians, wow, we have got a lot to do on this. I mean, it’s, it graduate students, uh, it is, it’s an open field. It really is. You, you can shoot 360 degree and you’ll find a topic that very little has been done.

So anyway,

Mark Howell: uh, well, and, and speed and speedways are such an important part. I mean, we look at them as being the venue where the cars and the stars do their thing. Uh, but when you think about, as, as Brian, you know, shows us in his book, when you think about what the track itself meant to the region, meant to the economy, meant to, to the, to the government, meant to the area where it was built, [00:55:00] um, you know, and then, then, then you can just kind of extrapolate from there.

What about Darlington in South Carolina? What did Daytona do for Daytona Beach? Um, I’m from Northeastern Pennsylvania. Pocono, uh, the Olis bought a spinach farm and had, uh. Uh, and, uh, and, and had a, a a three cornered triangular track built, uh, that was actually had one turn modeled directly after Indianapolis.

Um, and the idea of from that speedway and from that, that event, whatever race it happens to be, you branch out and you see the impact and the effect on as, as, as Don you just said, you know, 360 degrees around that region. And it’s, and it’s so much more than just, yeah, the, the car racing’s important, but boy, then you can go off in so many different directions and look at the influence [00:56:00] of these places and, and not only the influence on the sport, but the influence on where these things were built and, and what they meant to those regions.

Don Capps: More story time I was told. And, and Brian, I want you to understand this. I was told many, many a time by people who were auto racing historians that a lot of things did not exist. For instance, the Racing Rules to the Automobile Club of America, I found them and Automobile Magazine in 1901 and the Amendments in 1902, I found the first 1903 rules by the AAA Racing Board.

I was told they didn’t exist. On and on and on, but I think that’s the academics. W we dig, we’re persistent. Uh, and, and, but [00:57:00] we also leave a a, a, a trail of breadcrumbs because that’s what I may find important, I think, and that’s what I like about your book. Someone could pick your book up and continue to march.

That is important. Same thing with Paul, same thing. What you’ve done, mark, we, we can pick these works up and we have breadcrumbs because we, we run into brick walls on occasion. Uh, you know, the fact that Paul told me that there was not a book, even in Italian on the relationship between fascism, the, and the, uh,

Paul Baxa: motor.

There was, there is one book in Italian, one book. Yeah.

Don Capps: So outta how many on Italian racing, I’ve got shelves of these books.

Mm-hmm. [00:58:00]

Don Capps: And that just blew my mind. Yet here yet we, now we have, and again, i, I, I keep going back to it, a book that lays it out. Can people go and do more work? Of course, we open doors.

Paul has opened the door. Brian, you’ve opened the door. God, mark, you’ve opened many, many, many doors, uh, uh, for people. So this is why I think this discussion, this is why the ING Symposium exists to have these discussions, to have these people who are buffs but are darn good historians. They come up with topics I would’ve never imagined, uh, and, and, and personalities that, that when you start piecing those pieces together, suddenly you have a clear idea.

I mean, how many times we had someone talking about a European topic? Well, [00:59:00] we had the Italians would, would, uh, some years ago that I was blown away. There were things, I know a lot about Italian racing, I thought. Until they showed up and then they just went into things. I was thinking, how did I miss that?

Not necessarily, ’cause they don’t read Italian very well. It’s the fact that their brains were looking at those things and saying, there’s more to this. That’s, that’s what Paul did and that’s what you did, Brian, on that, because again, where do, where do you go next? That, that’s one of my questions. Where do you go next with this in Motorsport?

Brian Ingrassia: That’s a, that’s a good question. I was gonna say something different, but I’m, I’m not sure the answer to that question. I was just gonna say that, um, you know, there’s this, I I think that I, I I wish that, you know, um, mainstream historians would take things like sport more [01:00:00] seriously. Oh, definitely. Here’s the reason.

I I, I, I think back to that Amy Bass, uh, round table that you mentioned earlier. Uh, I remember reading that when it came out. I’d love to. I would’ve loved to have been part of that, um, discussion in the Journal of American History. But, you know, there’s this great book, um, by a, a retired historian at Princeton, a guy named Dan Rogers, who wrote a book called Atlantic Crossings, and it’s all about like liberal progressivism in the late 18 hundreds, early 19 hundreds.

And these Americans who went to Germany and they studied in German universities and people who went to England and learned about the social settlements. And they came back and they did a lot of these things in the United States. But one of the things we’ve been talking about is how something like that is happening with, with auto racing and automotive spectacle, because yeah, the people in Europe are paying attention to Indianapolis.

But where did Carl Fisher get his idea in the first place? You know, he sees Brooklyn’s in, in England, he sees what they’re doing there and he says, we should have one of those back in Indianapolis. And I guess you could, one way you could take that is you could say, okay, well, um, we should be looking [01:01:00] at kind of these, these international transnational, you know, cross Atlantic.

Kind of, um, connections with sport. But I, I think, again, sport is, it’s not just telling us something about sport. It’s telling us something about how people are using their time, uh, what they’re investing in, what they’re investing their, their money in, but also their enjoyment. Um, and, and auto racing.

Again, I I, I think Mark put it really well is that, that the story of Indianapolis, it’s not just about the cars, it’s not just about the races, but it’s about all the other things that are going on around them, you know, what the spectators are seeing, but also how are they getting there and how the cities are put together and things like that.

So, I, I mean, I’d be really happy if we, we kept thinking along those lines and we said, okay, it’s a, I mean, the racing itself is, is a really important thing that we need to understand. But, but how, what does it tell us about everything that’s going on around those racetracks as well?

Don Capps: I think, mark, you said one time.

The most important thing about motor racing is not the cars and [01:02:00] the tracks, it’s all the stuff around it. Yeah. And it’s the cultural aspect. By the way, you reminded me of something I had to, I just came across as after looking for it for like about five years now. Uh, sport, a cultural history by Dr.

Richard Mandale, who was one of my professors in graduate school. This is back when sport history, you could do Olympics and you could do baseball in America, and football was coming along and you could do cricket, football, soccer, uh, and Olympics in Europe. And he, he really lays it out quite well. So that’s a very good point.

And, and I just, there’s just so many things that I, I, I, where we need to go with this. Uh, uh, thank goodness for the, uh, inger because every year. Every year something pops up. [01:03:00] That, uh, surprises me.

Mark Howell: Well, and, and what I like too, this since, since, we’ll throw Dan in here sort of in absentia, uh, one of the, one of the points that, that he made one time is that the thing about racetracks is that as opposed to road racing, and especially in the, the old days of like the Glidden tour and things like that, and the Vanderbilt Cup where you had kind of point to point sort of racing, having a an enclosed course meant fans had something to see.

They could stand by the fence or sit in a grandstand and watch the cars go around and around repeatedly. And it was actually entertainment. It was more than just watching a car go by in a cloud of dust and that’s it. Suddenly you had this kind of creation of an economy. Well, you had to buy a ticket to get the seat.

Then while you’re watching the races, you’re probably gonna get thirsty. So you could [01:04:00] buy something to drink and here’s a program that tells you who’s out there racing. And everything just kind of blossoms out of that idea of how do we make something where people have something to watch, where they’re gonna sit here and, and have hours of entertainment.

And, and that, that to me is fascinating. That idea that, you know, and that’s, that’s what Indianapolis, you know, still does. I mean, the idea that, yeah, the races are exciting, but there are things there for people to do. You know, there’s everything from, you know, the VIP suites to, you know, the snake pit. Um, but there’s something for everybody, you know, and if, you know, whatever floats your boat as they say,

Brian Ingrassia: I think you’ve hit on a important idea.

If, if you don’t mind me just jumping in, um, it’s, it’s, it’s a way to commodify the race, right? It’s to commodify it’s hard to charge tickets for a road. You could do it, but it’s hard. Whereas with a, a, a closed course, like you said, you, you could control access to the stands, [01:05:00] but you can also watch the person go by again and again and again.

And what’s interesting then is it’s not just the race itself is commodified, but the racers and the racers too can become celebrities, can become commodified celebrity. Um, and there’s, there’s one place in the book where I, I, I’m not a big Marxian, but there’s kind of a, a marxian moment where I say something like this is, this is basically how automobility becomes commodified.

Right. That it gets turned into a bingo. Yeah. What a, a use value, right? Or a market value that it goes from like, okay, you can watch cars to like, oh, we can like make money off of pay, you know, charging people to watch the symbolism of cars go by again and again and again. And I think that’s, that’s hugely important.

I, I think Dan’s exactly right about that, that, that the closing the course, which I, I think is sort of an American innovation that really, it, it, it commodifies the event. So I’ll talk. Yeah.

Don Capps: And you see that right about 19 0 1, 19 0 2. Particularly about then [01:06:00] because the relationship, motor racing culture in America, you have to understand bicycle racing and you have to understand the two forms of horse racing, harness racing, and thoroughbred racing, which are different, different rules and different organizations, which again, my ignorance was only exceeded by my lack of knowledge on that.

Uh, so you see that it is an inter, it’s entertainment basically racing motor sport is a sport. I keep talking, you know, I, I see it as a sport, less as a technical thing, mean people get, 99% of the books seem to be about. Gear ratios and bores and strokes and tire sizes and stuff. I’m more fascinated in what Paul wrote about.

I wanna know, how did this ideology [01:07:00] accommodate this thing? The Mila Mela. Holy moly. Try to explain that outside of, uh, in the on and on and on.

Paul Baxa: Yeah. So, yeah. Thanks Don. Uh, yeah. So Brian, um, one, one thing about your book is when, when I finished reading it, I wanted to know more. I mean, is is there a plan to kind of tell the rest of the story sixties, seventies, and nineties and, or is that it?

Yeah,

Brian Ingrassia: I’ll, I’ll be honest, I don’t have that plan. Mm-hmm. I haven’t, um. I haven’t, uh, um, said I’m not gonna do that. Uh, my first book was football. My second book was auto racing. I, I’ve written a big chunk of my third book, and I, I hate to admit it’s baseball, which is actually probably my favorite. And if you’ve been to Nash, you know that Nash used to be like all baseball and boxing.

It’s actually kind of, it’s weird. Like at a certain point Nash was like, yeah, we’re not really gonna do baseball anymore. That’s passe. [01:08:00] And I’m like, no. I think there’s a new way of looking at the business of baseball, of organized baseball, that that’s kind of what I’m working on. But I, I suspect at some point I’m gonna get pulled back into the story of, um, 1960s, 1970s, uh, auto racing.

Um, I’ll confess, um, a while back, uh, Dan Nathan, who’s the editor of the Journal of Sport History, asked me if I wanted to do, uh, he’s like, you know, we never reviewed that movie, um, uh, for versus Ferrari. When it came out, he’s like, do you wanna do a book review and or a, a movie review? Review? And at first I misunderstood him.

I thought he wanted me to review the book, but that’s based on, uh, go like Hell, I think is the title. And I said, well, I could do do that. And I, I ended up reviewing both of them for the journal. Um, and, and I loved, I loved the book. The movie was good too, but I really loved that book. And I was like, oh, there’s some really interesting stuff going on in the 1960s in terms of automobiles.

You know, I think about my dad was, you know, he owned a muscle car too in the 1960s. He had like a [01:09:00] 1967 GPO, I think. Mm-hmm.

And,

Brian Ingrassia: uh, part of me is like, now I wanna know more about what was going on in auto racing more generally in the sixties. So I, I’m not saying I’m gonna do that book, but it, it, it may pull me back in at some point in time, but for now, baseball is kind of where I’m going for the next big book project.

At least. But yeah. You know,

Mark Howell: and there’s that international sort of, you know, combination that we see in Motorsport. I think about the 1965 Indianapolis 500. Mm-hmm. You’ve got a Lotus powered by a Ford engine, driven by a Scotsman, and the, the people servicing the car are a NASCAR pit crew from Virginia, and they go on to dominate the Indianapolis 500 and win.

And, uh, yeah. And people don’t find that interesting. Historians don’t see that as having some level, there’s some fascination there with how all of those pieces came together at that particular point in time. [01:10:00] Um, it, it, it boggles it, it boggles, the imagination occurs, you know,

Don Capps: uh, five minutes, gentlemen, five minutes.

Mark Howell: I’m kind of a one trick pony. But, um, uh, I, you know, that those kinds of stories and Indianapolis is really such a. Such a hotbed for those kinds of, of those kinds of stories.

Paul Baxa: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Because it seems that in the sixties with, with the British, uh, innovation comes back. Uh, I may, I’m not an expert on in the 500 history, but it would just be interesting to see that, you know, now you get into the sixties, you have the museum, you have the whole nostalgia, you got the invented traditions, like the drinking of the milk and all that, which I think you also bring out brilliantly in your book.

So yeah. So it’d just be interesting to see what direction that, how that goes in the sixties. So,

Mark Howell: and, and didn’t they just, they they are in the process of rebuilding or remodeling the museum at Indianapolis?

Don Capps: Y yeah, it’s shut down for a while. It will not be open there [01:11:00] cleaning house for, to a large extent, um, for various reasons.

Um, mostly because. They found that they had all the stuff that had nothing to do with Indianapolis Speedway and the race, or Indianapolis for that matter. And uh, so that’s basically going where it stands right now. Um, uh, Jason Van Sickle, uh, is leading that effort. Jason is one of the, the really good guys as far as I’m concerned.

He has done a super job there and I, I had to get it off because exactly what Paul said, the mystic cords of memory, the transformation of tradition, American culture, uh, don’t drop it on your foot all these years later. Um, and it’s, so I have this whole bunch of books that I keep, like Brian keeps, you know, [01:12:00] that I keep going back to, uh, and it all seemed to be just like Mark and I relationship started on with the word culture.

I mean, our official mission for the Aring is the, the first turn meet the cultural turn. And that’s what we were trying to push for years and years and years now. Uh, Mike thought it was funny, uh, but after he thought about it, he says, you know, that’s pretty much what we’re talking about. Because when you look at Watkins over the years, it’s a cultural site.

It really, I mean, that’s a village of only a couple thousand people and then you have over a hundred thousand people show up on a weekend.

I mean, when the first time I went there, uh, we just come, I just came back from Europe [01:13:00] and it was maybe 20,000 and that was a huge ground. Then it got bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger. And when I, the last one I went to sometime, I guess like 79, 80, whenever it was, no, nobody batted an eye that it was like 75 or 80,000 in this little village whose sole purpose like Indianapolis was a race

Mark Howell: and to bring all those foreign teams to Oh yeah. That little hamlet, you know? And, and, and, and, and that was just expected. And that’s what you did that was on the schedule and you showed up and, and nobody batted an eye about that.

Don Capps: I had people in the UK would see something with me and he said, you know where Watkins Glen is?

Yeah. I go there all the time. And they’d started to talk about it. Said My one trip to America to a race was at Watkins. They [01:14:00] still talk about that. So anyway, uh, I think we’re getting close to time. Any, yes’, any closing remarks?

Paul Baxa: Just looking forward to, uh, seeing you all, all you guys virtually and in person in a, in a week or so.

Absolutely. So thank you for this great talk.

Brian Ingrassia: Thank you all for reading and inviting me here. I appreciate it a lot. Thank you.

Don Capps: Be stay a part of the group. You’re, you’re always welcome. Believe me. Believe me. Uh, thank,

Mark Howell: thank you for writing this book, Brian. Oh yeah. It, uh, it’s, it’s, it’s, it’s changed our outlook on a lot of things, I think, or at least, at least supported and, and, uh, and has kind of bolstered up our feelings about that relationship between culture and, and motorsport.

And, uh, likewise, real quickly, I’m, I’m sorry I’m not gonna see everybody in person, but, uh, I will be lurking around. In a virtual digital form there somewhere over the weekend. And, [01:15:00] uh, um, and I hope everyone has, uh, safe travels getting to and from, uh, the track. So,

Don Capps: so thank you Paul, as always. Thank you, Brian.

Of course. Thank you, mark. Uh, and, and Dan, I’m gonna work Dean in somehow and all this. So thank you so much for taking your time and uh, again, uh, it’s always a pleasure, uh, to talk with you guys. I really appreciate it. Thank you, Brian, for, for joining us. So thank you guys. I hope we didn’t ruin your lunch.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience. And has been Edited, Remastered and Produced in partnership with the Motoring Podcast Network.

Other episodes you might enjoy

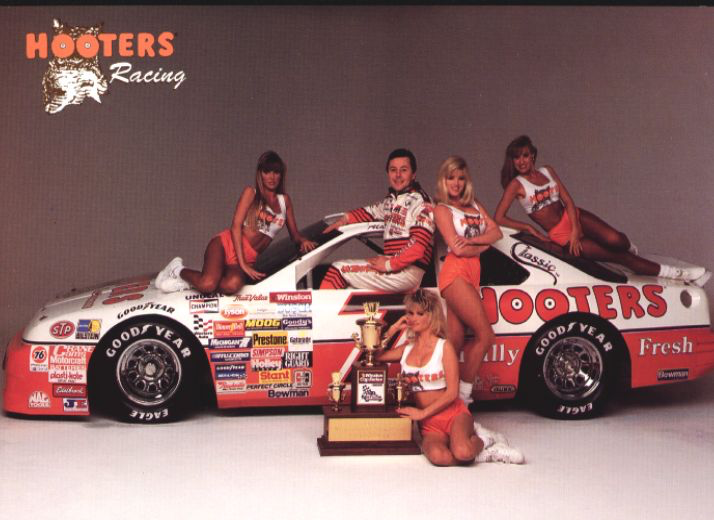

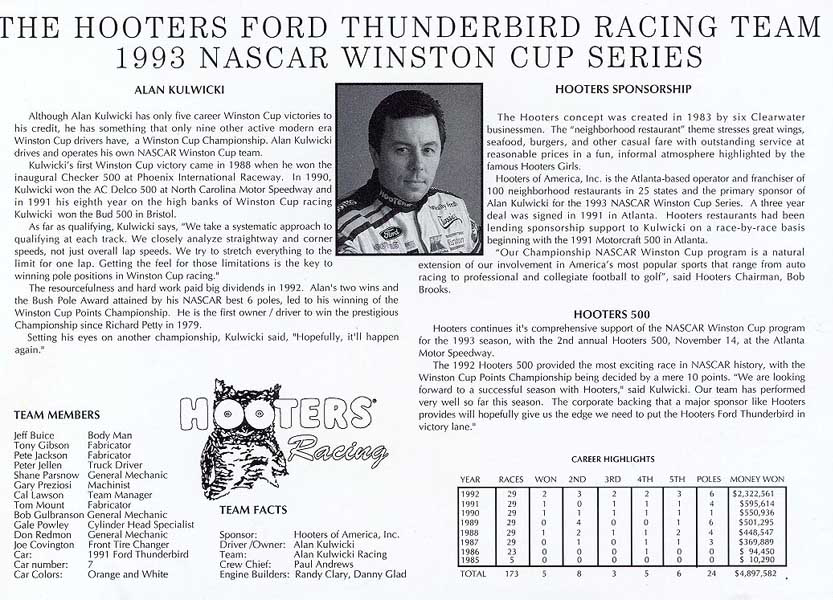

In mid-November 1992, thanks to leading 103 laps in the Hooter’s 500 at the Atlanta Motor Speedway, Alan Kulwicki was able to secure the five bonus points for leading the most laps in the race, which would, in turn, then allowed him to finish second to Bill Elliott and yet still secure the Winston Cup title. Bill Elliott, driving for Junior Johnson, led for 102 laps, the difference of that one lap deciding the championship in the favor of Kulwicki, despite Elliott winning for the fifth time that season.

It was, of course, somewhat more complicated than that. There were, after all, twenty-eight events in NASCAR’s Winston Cup Series prior to the Hooter’s 500 in November. The Bill Elliott versus Alan Kulwicki battle for the title as the race wound down was not necessarily what might have been expected when the green flag dropped to start the race, which was, incidentally, the last for Richard Petty and the first Winston Cup start for Jeff Gordon. Coming into the race, the points leader was Davey Allison, not Elliott. The lead for the championship had changed after the previous event, the Pyroil 500 at the Phoenix International Raceway, two weeks previously.

Alan Kulwicki, during the 1992 season. Photo: Hooter’s

Davey Allison held the lead in the points standings for much of the season before Elliott moved past him at the Miller 500 at the Pocono International Raceway in mid-July. Elliott was about to take a slim nine-point lead in the standings thanks to Allison having a massive crash that left him with a broken right collarbone, forearm, and wrist. That Allison was not injured more severely was little short of a miracle given that his Ford Thunderbird rolled eleven times, slammed into the guardrail and ultimately came to rest on its roof.

At the next race, the Diehard 500 at the Talladega Superspeedway, using Bobby Hillin Jr. as a relief driver to be credited for finishing third, the injured Allison managed to take a one-point lead over Elliott. However, from the Budweiser at the Glen in August until the Phoenix race, Bill Elliott held the lead in the Winston Cup standings. It was not without problems, however. He blew an engine at the Goody’s 500 at Martinsville and suffered with an ill-handling car during the Tyson 400 at North Wilkesboro, relegating him to a 26th place finish. He then hit the guardrail and broke a sway bar during the Mello Yello 500 at the Charlotte Motor Speedway, spending eighteen laps in the pits for repairs. But after the AC-Delco 500 at Rockingham, with a sixth-place or better finish at the remaining two events on the calendar (Phoenix and Atlanta), Elliott was in a position to clinch the Winston Cup championship.

Tribute Card issued by Hooter’s after Alan Kulwicki won the 1992 Winston Cup Championship that was used during autograph sessions. Credit: Hooter’s

At Phoenix, Elliott’s Thunderbird cracked a cylinder head and started overheating, relegating him to a thirty-first place finish. This allowed Allison to retake the points lead with his win. A fourth-place finish by Kulwicki moved him past Elliott and into second place in the standings. As they headed towards the season finale, Allison was now the leader, with Kulwicki thirty points back, and Elliott forty points in arrears. Also within striking distance, mathematically or at least possibly or theoretically, were Harry Gant, Kyle Petty, and Mark Martin. The latter three would require some very serious problems among the top three given that Gant and Petty were over fifty points behind.

What all this meant was that to be the 1992 Winton Cup champion, Davey Allison simply needed to finish fifth or better to ensure the title regardless of whatever the others might end up doing. Plus, he had a thirty point buffer over Kulwicki with an additional ten points on top of that over Elliott. In other words, it seemed quite reasonable that Davey Allison would emerge as the 1992 champion, especially in light of the difficulties facing Kulwicki and Elliott, not to mention Allison coming off a victory at Phoenix, having the momentum that success creates going into the finale.

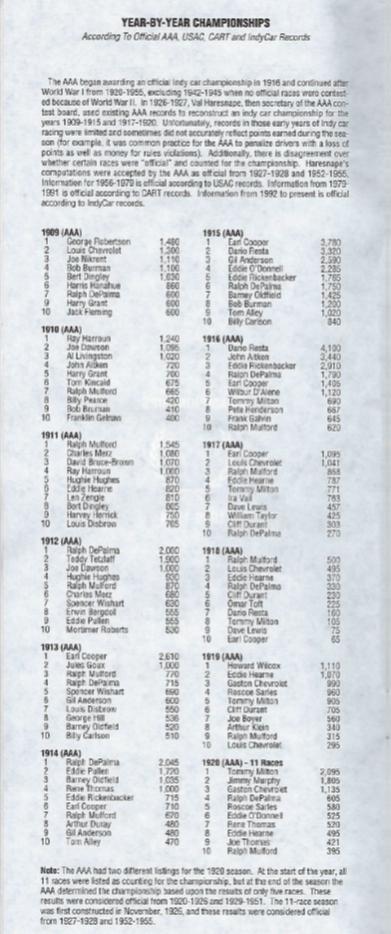

The Atlanta race was run under a points schedule that was put in place by NASCAR beginning with the 1975 season. It replaced a series of point systems that were often confusing to fans and teams alike. Until the 1968 season, the Grand National series, as it was then known, used a combination of prize money and distance to determine the points awarded for an event. In 1964, for example, points were awarded using sixteen different schedules based upon the prize money posted and the distance of an event. From 1968 60 1971, this somewhat chaotic system was replaced by a very simple three-tiered system: points were awarded for events less than 250 miles, those between 251 and 399 miles, and those 400 miles or longer.

In 1972 and 1973, points were awarded based upon the finishing position and then with additional points given according to the number of laps completed in a race. If that system wasn’t enough of a bookkeeping nightmare, in 1974 NASCAR managed to outdo itself: Winnings from purse posted for an event, with qualifying and contingency awards not counting, multiplied by the number of races started, with the resulting figure divided by 1,000 determined the number of points earned in the championship. Needless to say, it turned out to be so hopelessly difficult to compute that even the teams were more often than not often confused trying to figure it out. Although the 1974 system has been the subject of a massive case of organizational amnesia in Daytona Beach, the system was clearly intended to reintroduce one of the major components of how NASCAR – and Big Bill France in particular – weighed the early points system by giving emphasis to the prize money being awarded.

In 1975, Bob Latford – usually referred to as a NASCAR “historian,” but in reality, a public relations flack for the organization who also just happened to be a high school classmate of Bill France, Jr. – devised a system that was used from 1975 through the 2003 seasons. It awarded points on a sliding scale in increments of five, four, three, two, and one down to fifty-fourth place, beginning with 175 points for first place. Points were awarded for an event regardless of the distance or the purse that was posted. Five bonus points for leading a lap with an additional five points for the driver leading the most laps in a race.

This meant that a driver finishing second in a race, earning 170 points, could earn five more points for leading a lap, and another five points for leading the most laps. In other words, with the winner getting an automatic additional five points thanks to leading a lap, earning 180 points, it also meant that a driver finishing second, 170 points, could equal the points awarded to the winner by leading the most laps in a race, therefore adding ten bonus points to his score, also earning 180 points.