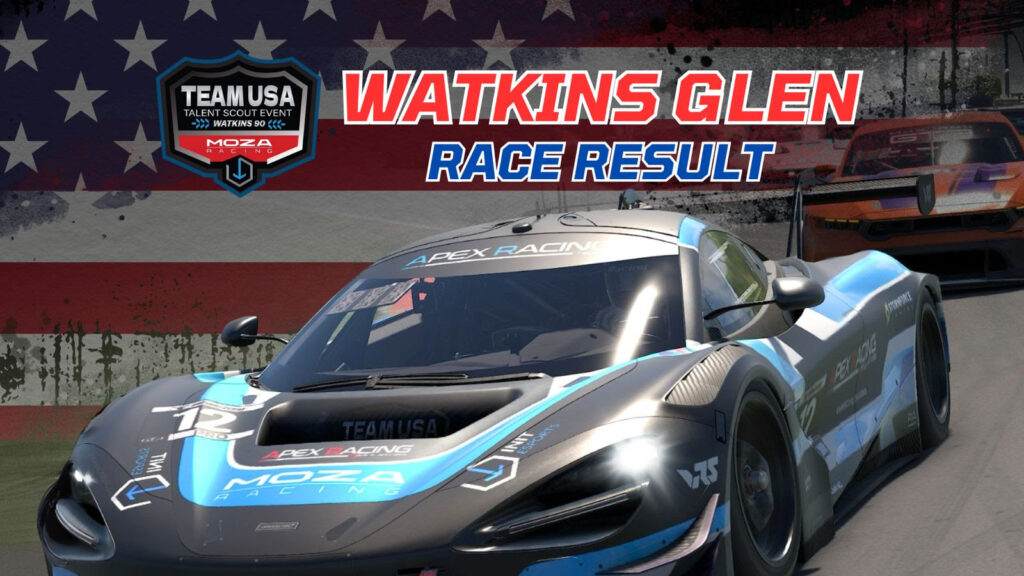

The roar of engines, the scream of tires, and the pulse of passion lit up Watkins Glen as nearly 40 of America’s top sim racers battled it out in Event 3 of the Team USA Talent Scout Series on iRacing — a pivotal stop on the road to Esports Olympic glory and international competition.

The roar of engines, the scream of tires, and the pulse of passion lit up Watkins Glen as nearly 40 of America’s top sim racers battled it out in Event 3 of the Team USA Talent Scout Series on iRacing — a pivotal stop on the road to Esports Olympic glory and international competition.

Presented with the generous support of MOZA Racing, this electrifying GT3 showdown was more than just a race — it was a chance to be seen, to be discovered, and to take one step closer to representing the United States on the world’s biggest esports stage.

The Path to the Podium — and Beyond

From promising rookies to seasoned veterans, every driver on the grid knew the stakes: perform now, or risk being left behind. With a future spot on Team USA Esports potentially on the line, the competition was ruthless — and unforgettable.

Jordan Johnson of Apex Racing Academy put on a masterclass in strategy and consistency, recovering from mid-race challenges to claim victory and the coveted MOZA KS Wheel. Michael Janney and Xander Reed, both representing Coanda Esports, joined him on the podium, proving that racecraft and resilience still rule the road.

But this event wasn’t just about winners — it was about talent discovery, and shining a spotlight on the future stars of motorsport.

MOZA Racing Raises the Stakes

MOZA’s incredible support made the event even more rewarding. With high-end racing gear and points up for grabs, MOZA helped turn digital dreams into tangible rewards:

Prize Highlights

- MOZA KS WHEEL – Jordan Johnson

- MOZA GS V2P GT WHEEL – Aaron Ramón

- 200 MOZA Points – Steven Anderson, Nolberto Alvarez Jr., Xander Reed

- 100 MOZA Points – Arron Brown, Jason Walat, Marc Lerwick

Their commitment to empowering the sim racing community continues to fuel the growth of the sport and the dreams of competitors nationwide. For all TEAM USA Talent Scout Events MOZA will offer a prize for the winner, a participant, and MOZA points to 6 randomly selected drivers.

Watch the Replay

Missed the action? Relive every moment of this cinematic race on Twitch and YouTube. From Turn 1 chaos to last-lap heroics, this one was built for the highlight reel.

Influencers and Impact

A lineup of top-tier influencers joined the grid, bringing energy, visibility, and a powerful sense of community to the event. Their presence is a testament to sim racing’s growing cultural relevance — and its thrilling future.

Don’t Just Watch — Join the Race

Think you’ve got what it takes? Registration for the next Team USA Talent Scout event is now open. Whether you’re a rising star or a seasoned pro, your shot at representing the red, white, and blue starts here. The full calendar of events can be found at www.initesports.gg/carsim

Special thanks goes to TRACKILITIOUS as our fantastic community partner, Mike Nause and Jackson Lamb, our amazing commentators and everyone else working tireless behind the scenes to make those events a success.

Follow @InitEsports on all platforms to stay updated, register for the next race, and be part of the movement redefining motorsports from the screen to the speedway.

This is more than a competition — it’s a calling. The road to Team USA starts with your next lap.

Let’s race. For media inquiries, please contact: info@initesports.com

About MOZA Racing

MOZA Racing is a global leader in sim racing hardware, known for delivering high-performance, precision-engineered equipment designed for competitive racers and enthusiasts alike. With a commitment to innovation and community engagement, MOZA continues to set the standard for the future of sim racing.

About Init Esports

Init Esports is the leading organizer of sim racing competitions in the U.S., with a focus on diversity, inclusion, and talent development. As the architect behind Team USA Talent Scout Events, Init Esports is pioneering the future of sim racing with purpose and passion.

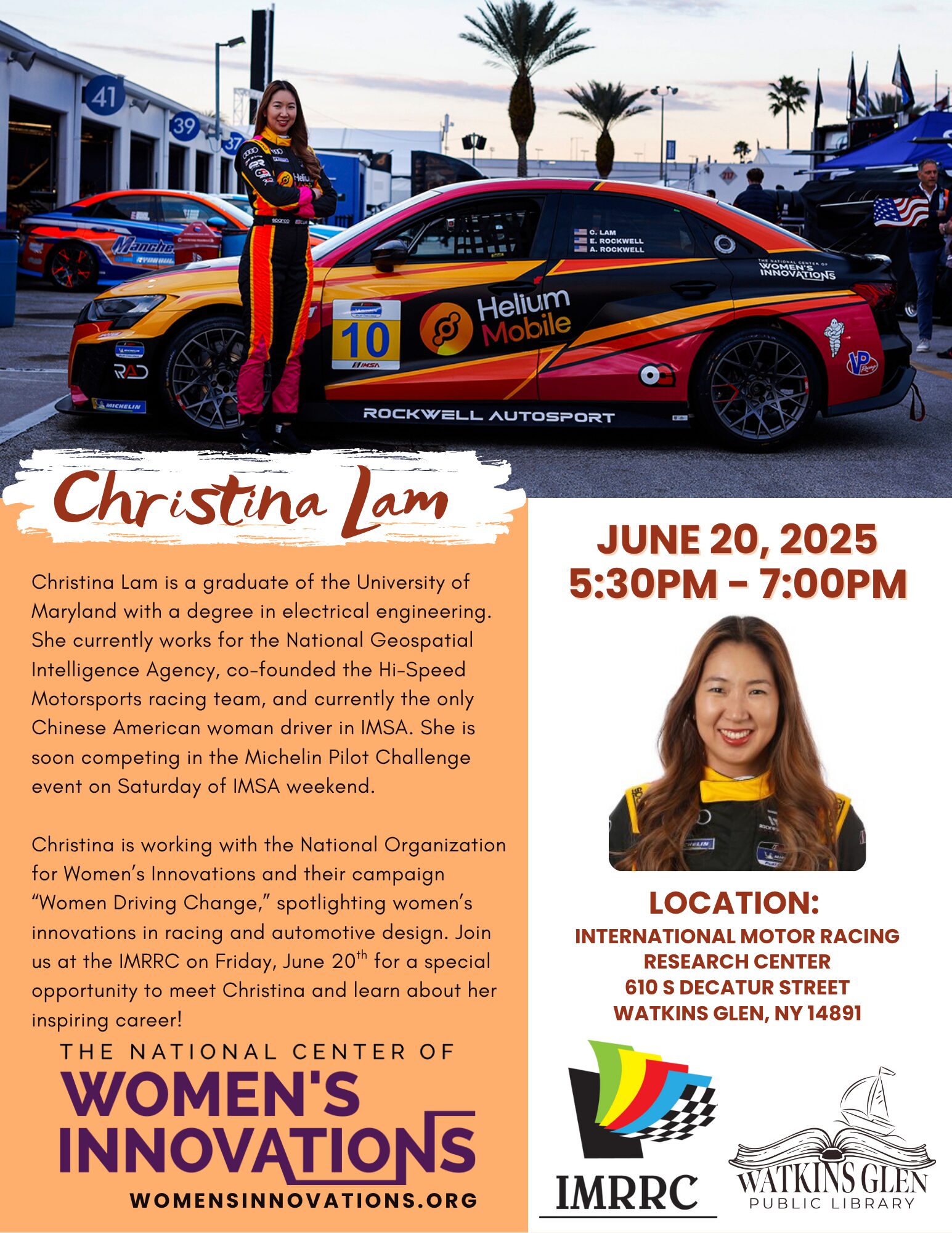

The 1966 McLaren M1B was a lightweight, fiberglass-bodied sports prototype developed for the Can-Am series, featuring a spaceframe chassis and typically powered by a big-block American V8 engine. As an evolution of the M1A, the M1B marked McLaren’s growing presence in North American racing, showcasing Bruce McLaren’s engineering ingenuity and competitive ambition.

Unique features: Drivers in 1966: Frank Gardner, Bob Bondurant and Jacky Icyx

Quote from the owner, Raymond Boissoneau: “My most memorable win was at Zwartkops, Johannesburg, South Africa. I never thought that I would be in a country that is so beautiful doing something that I love to do. I also won the combined overall fastest time. After traveling 10,000 miles, it was the best victory I have ever had. They had the largest spectator crowd they have ever had for this historic race.”

Now on display at the IMRRC, come visit us and see it in person!

Just in time for the 2025 Le Mans, Jordan Taylor stopped by for an “Evening With A Legend” podcast episode discussing his previous 8 attempts at the 24 Hours of Le Mans and what it means to be back this year with Cadillac and Wayne Taylor Racing at the front of the pack! We were proud to co-sponsor this Motoring Podcast Network production with our friends at the ACO USA. Click the play button below to tune in! (For more IMRRC podcast episodes, click here.)

Jordan Taylor, who has established himself as a formidable competitor at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, showcasing his exceptional talent in endurance racing. As a long-time factory driver for Corvette Racing, Jordan has played a key role in over eight Le Mans campaigns, contributing to podium finishes and class victories. Known for his speed, consistency, and racecraft, he has mastered the demands of the Circuit de la Sarthe, excelling in both day and night stints. His adaptability and strategic mindset have made him a crucial asset to his teams, solidifying his reputation as one of the top endurance racers of his generation.

There’s more to this story!

Check out the Uncut, Unedited, Unfiltered behind the scenes version of this episode…

As an ACO USA member you’re invited to join Evening With A Legend, a series of presentations exclusive to ACO USA Members where a Legend of the famous 24 Hours of LeMans race will share stories and highlights of the big event. Consider joining the ACO USA today!

Membership into the Automobile Club de l’Ouest – the founder and organizer of the 24 Hours of Le Mans – is open to all! The Club hosts events in Le Mans and around the world, attracting fans who enjoy their shared passion for motoring and motor racing. Tired of sitting in the pits? Explore the many advantages of becoming an ACO Member today!

Membership into the Automobile Club de l’Ouest – the founder and organizer of the 24 Hours of Le Mans – is open to all! The Club hosts events in Le Mans and around the world, attracting fans who enjoy their shared passion for motoring and motor racing. Tired of sitting in the pits? Explore the many advantages of becoming an ACO Member today!

A number of automotive-history activities are planned. We hope you will join us for a weekend of car talk and celebration.

(DAY 1) Saturday, September 20

Tour the Sloan Museum of Discovery – History and Durant Automotive Galleries

1221 E Kearsley St, Flint MI 48503

[1 mile from Factory One]

1PM – 3PM

$10 special rate

Tour of the Kettering Archives at Factory One

5PM-6PM

Free of charge

2025 Society of Automotive Historians Annual Award Banquet

Saturday, September 20, 2025

Durant-Dort Factory One

303 W. Water St., Flint Michigan 48503

6PM-9PM

Menu and cost TBA

Speaker: Jim Secreto, retired Detroit automotive photographer and collector extraordinaire of automotive advertising art. Using examples from his collection, Jim will talk about automotive illustration before the digital age.

(DAY 2) Sunday, September 21

Golden Memories Car Show – Exclusively for original or authentically restored vehicles produced in 1975 or earlier

Flint Cultural Center [1 mile from Factory One]

1310 E Kearsley St., Flint MI 48503

9AM-4PM

Free of charge

LODGING

Special-priced rooms are available for September 19 & 20 at two local hotels.

Mention the Society of Automotive Historians when making reservations.

Hilton Garden Inn Flint Downtown

110 W Kearsley St, Flint, MI 48502

810 233-9110

Short walk to Factory One

$139 per night

Reservations must be received by Friday, August 29

to receive special group rate.

Hyatt Place Flint-Grand Blanc

5481 Hill 23 Dr. Flint MI 48507

810 424-9000

12-minute drive to Factory One

$119 per night

Reservations must be received by Friday, August 29

to receive special group rate.

If you have questions or would like more information, contact Chris Lezotte.

Thanks to a grant from a generous long-time donor, the IMRRC has embarked on an ambitious digitization program, beginning with a selection of films from archives. Among the first group of films converted are 8 and 16mm examples that, naturally, feature racing in Watkins Glen in the 1950s and 1960s but also other venues such as Indianapolis, Bridgehampton and Lime Rock. These films and other s will be made available on the IMRRC’s YouTube channel.

Example of the Assorted Races from the Mal and Charlotte Currie Collection (99A008) on 8 mm film. All races from 1964.

- Glen Classic: Jim Hall in #66 (he won the race) and Tex Hopkins

- Watkins Glen Grand Prix/USRRC: Janet Guthrie (car #15) and in orange searching for something

- US Grand Prix: Jim Clark and Graham Hill (the latter won the race that year)

- NASCAR: Richard Petty parking his car (#43)

All that was missing were the Nitro fumes!! On Saturday, May 10 the IMRRC’s first Center Conversation program of the season was presented to a large, enthusiastic crowd of ‘Straight Line’ fans. Dean Johnson, the promoter of the track from 1964 to the track’s closing in 1974 and Jim Oddy, long time competitor at the track as well as drag strips around the country – and a member of both the NHRA and the International Drag Racing Hall of Fame – were the featured speakers and both took the audience back to the “Golden Age” of drag racing.

The iconic SUNDAY…NIAGARA radio ad boomed throughout the auditorium to both open and close the program. Camaro and Corvette competition drag cars were displayed outside the Center by the folks from Skyline Dragway in Tioga Center. Dean generously donated a huge collection of photo albums and other Niagara Dragway memorabilia to the Research Center several years ago, and those fantastic images and the commentary from Dean and Jim took the audience back to another era of racing as well as a very entertaining few hours. A great program and a fun afternoon enjoyed by many. If you weren’t there in person, the entire program can be found on the IMRRC’s YouTube channel.

Donald C. Davidson was the historian of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway from 1998 to 2020, and the only person to hold such a position on a full-time basis for any motorsports facility in the world. Davidson started his career as a statistician, publicist, and historian at USAC. His radio program, The Talk of Gasoline Alley, is broadcast annually throughout the “Month of May” on WFNI in Indianapolis, and he is part of the IMS Radio Network.

Davidson is also a member of the Auto Racing Hall of Fame, the Richard M. Fairbanks Indiana Broadcast Pioneers Hall of Fame, and the USAC Hall of Fame. In 2011, he visited the IMRRC to recount some of his stories and memories from America’s Great Race. This remastered center conversation is introduced by the late Michael R. Argetsinger, with an opening presentation by historian Joe Freeman from Racemaker Press.

This episode was originally recorded in 2012 at International Motor Racing Research Center and has been remastered for this podcast.

Highlights

-

00:00:00 Introductions

-

00:05:00 Joe Freeman’s Presentation on Indy Roadsters

-

00:06:25 The Evolution of Indianapolis 500 Cars

-

00:19:32 Donald Davidson’s Q&A Session

-

00:55:27 Lotus and Ford’s Indianapolis Journey

-

00:56:14 American Red Bull Special

-

00:58:07 Restoration and Historical Cars

-

01:00:25 Friendship and Enthusiasm in Racing

-

01:02:33 Mel Kenyon: The Underrated Driver

-

01:21:16 Future of Motor Racing

-

01:29:13 Honoring Indianapolis 500 Drivers

-

01:41:32 Conclusion and Acknowledgements

This episode is part of our HISTORY OF MOTORSPORTS SERIES and is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Break Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce and the Argo Singer family.

Crew Chief Eric: Donald C. Davidson was the historian of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway from 1998 to 2020, and the only person to hold such a position on a full-time basis for any motorsports facility in the world.

Davidson started his career as a statistician, publicist, and historian at usac, his radio program, the Talk of Gasoline Alley as broadcast annually throughout the month of May on WFNI in Indianapolis, and he is part of the IMS Radio network. Davidson is also a member of the Auto Racing Hall of Fame, the Richard m Fairbanks Indiana Broadcast Pioneers Hall of Fame, and the USAC Hall of Fame in 2011.

He visited the I-M-R-R-C to recount some of his stories and memories from America’s Greatest Race, the Indianapolis [00:01:00] 500. This Remastered Center conversation is introduced by the late Michael Argetsinger with an opening presentation by historian Joe Freeman from Race Maker Press.

Audience: My name is Glen Eckhart.

I, I work next door for those who dunno me. Today we’re gonna hear two great speakers, Donald Davidson and Joe

Crew Chief Eric: Freeman focusing on in cars in Indianapolis. So that said, I’ll bring Michael Art celebrated motor sports author. We still have some of his books. If you haven’t finished your collection of Michael’s books,

Michael R. Argetsinger: we still have some, so.

So Michael,

thank you all for being here. We really have a wonderful program. Linda, as the community relations director for the research center, does such a wonderful job every year putting together this wonderful series of center conversations. And our two speakers today are on a subject I think near to [00:02:00] everybody in America who loves racing.

Whether you have dirt track towards cars or Formula One, we all want, 8,500 is 500 is really part of the fabric of, of our American life, in my view. Perhaps some of you feel the same way. Years ago, before it was on television, we remember sitting at the earliest years, perhaps beside our father, later years on our own listening to the radio.

And then as the years went by, we began to get television coverage. And, and when we go to this 500 itself, it’s a new, for many of us, the pageantry, the tradition. Indianapolis 500 is truly the world’s great race and it’s America’s treasure. There are two speakers today, Donald Davidson is our, is our featured speaker, distinguish historian at the 500.

I’m gonna speak a little bit more about Donald in a moment when he. To the podium, but uh, the first grade here from very special guy who has come here [00:03:00] today from Boston, Joe Freeman, and you probably roll at the center, he saw the beautiful Joe Hunt Magneto special, which belongs to Joe. Now, Joe owns that car, but he’s also a Vinny’s racer.

He races that tells him he’s even tried it on some road tracks where it’s a real challenge, but it really excels and runs beautifully on the oval tracks like Milwaukee and Indianapolis, and. The other, uh, places where he has a chance to air it out. Joe runs a multitude of other vintage cars as well. He just came back from a Monterey, the, the famous historic race a uh, Curtis about, I think it’s about a 1951 or 52 vintage car.

He did very, very well out of the field. I think 32 cars finished fourth, and that’s good in any kind of racing that’s better than good. So Joe’s quite a guy. He’s also, he is the publisher of Race Maker Press. We’re so fortunate to have Joe behind his publishing company. So many wonderful titles come through his publishing company.[00:04:00]

It’s a tremendous contribution to the literature of our support. It’s a tremendous contribution to our support to have these precious memories maintained in such a handsome format. So now Joe is an interesting man and he starts to ob being an enthusiast. He has all these intellectual capabilities, but it really starts with, he’s a tremendous enthusia for this court.

He raced back in the intense days, perform the court, really proved his medal of bat. He has segued over the years now into image racing where he’s great supporter, but it goes beyond that. Joe was president of the American Society of Historians. He was also president of the Laws Anderson Auto Museum in Brooklyn, Massachusetts.

A very distinguished election that Joe was president of. And they said he was the um, president of the Society of Automotive. He’s a fine writer himself. It’s really a great pleasure to open our program today by bringing Joe to uh, point and I think, Joe, you’re gonna start right there. Is that right? Thank you very much.[00:05:00]

Every Big

Joe Freeman: Rock concert always has a solid open act and I’m the Open Act. There’s a much bigger act problem, and I thought about. What better than to bring the boys the toys? So this is a collection of cars, many of which won the Indianapolis 500 during the particular era. It was called the road strip era.

For those of you who are not familiar with that term, I’ll try to explain it. Uh, during the thirties and early forties, basically most American championship racing was going a mile and half mile dirt tracks where racing was pretty much a standard set. The engine was in front of the driver. The driver sat, the driver shot one underneath his legs, and it was called an upright.

The last upright to in the Indianapolis 500 is Troy Whatley. In the 98 I won 1952. Those cars, along with some front drive cars, had pretty much dominated the speedway up until that time. But people were beginning to realize that cars were front [00:06:00] drive were not only heavy, they were also difficult to drive at the Speedway.

As a result, they were seeking a better method. They were also seeking to save money by using the car that they ran for the national championship in dirt tracks all over the country. To win the Indianapolis 500 and a man by the name of Eddie Kuzma made, uh, that 98 car and basically to Rutman, who was very young at the time, but a real talent won the race.

But that really was kind of the end of the upright at Indianapolis because in the next year, two famous designers by the name of Travis Z Co, along with another designer by the name of Frank Curtis. Got together and decided to design a car with the standard 2 55 ER engine, a four cylinder, double overhead hand shaft engine that put out about 400 horsepower when it was tuned right and on alcohol.

What was unique about what Frank Curtis did is that instead of [00:07:00] having the engine straight up and down in the car with the drive shaft running between the driver, he lowered the whole weight by tilting the engine to the side and putting the driver beside the drive shaft and lowering the weight and the roll center of the car.

That was a huge advantage, and in 1952 when Rutman won, the only reason Rutman won is because when they brought out Bill Kovic, who he was injection special. Hillborn made the fuel injection why Kovich was leading and his steering broke, but he was way ahead and everybody real. Wow. Look at this thing.

This is faster than anything we’ve seen. As a result, it was called the 500 A. They made four of those cars. Pretty much everybody saw the light and said, wow, these upright, they’re gonna be hard to manage. That was the origin also of the term Roadster. I want to read from a book that if you don’t have [00:08:00] it, you should try to get it.

It’s one of the best books ever written on the technical aspects of the Minneapolis Cars by Roger Huntington. It’s the design and development of Unicar, and what he wrote was, so what was so special about this roaster? What was a roaster? Anyway, the trick that distinguished this new Curtis Craft 500 day, she, so you were simply offsetting the drive line, approximately nine-digit left center, and positioning the driver’s seat to the right from on the drive shaft level, plus the engine was til to three, six degrees to the right to lower it gravity.

Then because of the low seating of the driver, the body was more or less up around, again, only the driver’s head and shoulders projected out in contrast to the plastic screw type car where the driver and from this came a very rapid transition. The evolution was that upright cars and that initial 500, what were called rail frame cars, they were built around two major rails and bolted between.

That was the primary support [00:09:00] of the, of the car. Uh, there were bars to support the body, but the mainframe rails were these two large rails. Frank Curtis quickly realized that that is not necessarily the best way to go, and he began to modify the 500 A and literally produced the 500 B 500 C 500 d all with, interestingly enough different suspension designs.

All of these cars had a certain kind of suspension, um, that’s called floor bar or, um, torsion bar suspension, either laterally or cross in front of the car. So he was quite successful. In 1955 a Bob Schweikert won the race with a 500 C bill. Kovic won in 53 and 54 was tried to be killed in an accident out of his own making.

In 55, Bob Schweikert, they had passenger driver won with a 500 C in 55. Then a young man by the name of AJ Watson [00:10:00] who had been hanging around Indianapolis and who had uh, made something called the Toxin Hand Special, which was this famous facility. Car flew together out hitting metal climb, brought up to the Speedway.

They had a little trouble with it, qualified, but it didn’t finish the race. AJ Watson had his own idea about things. Instead of laying engine on the side, he moved the engine over to the left side of the car. And as a result, in 1956, pat Clarity took his first major car and also. AJ Watson fitted this car together with a space frame that means tubes welded together.

That became a pattern for all of the roasters. After that, as a space frame, tubes welded together to make the frame instead of two big rails down below. Very quickly, other people began to see the advantage of this. They changed the suspension and there there was innovation at the time. These, I brought these [00:11:00] two that are both 19 55, 19 56.

They’re both 500 C, 500 d, but the engine is put in a different place than where the winners were. So there was innovation going on at the time. Then an interesting man by the name of, uh, George Sally and a friend of his queen got together to work on, uh, for a man by Sam Leah’s proper pronunciation to produce a really, truly radical car.

That’s this car here, the winner in 57 and 58, the Sam Hanks and Jimmy Bryan, that lady, the engine absolutely flat, lowered the weight of gravity. The guy shaft, again, ran alongside the driver. They had to make some modifications for the offie to be able to do that, but this was a real groundbreaker. But Watson wasn’t to be deterred.

He went to work for a, a man by the name of Bob Wilke, uh, owned a successful company in Milwaukee called Leader Cards, [00:12:00] and he designed his, basically his standard Roadster for Bob Wilke. And in 1959, Roger Ward took that to the win. That became really the pattern for the rest of cars from then on, that is in the Roadster era.

In 1961, AJ Foy, one raced in a Watson copy. It’s fascinating that I, just discussing before this, Travis just copied that Absolutely. Rail for rail from Watson. Watson didn’t seem to care. One of the deals that Watson had made with Bob Wilke was that he would be allowed to make cars for other people, but Floyd Travis just made this car and AJ Point won his first 500.

With that, the same time. They were all driving dirt cars as well. They were still driving uprights. Again, the majority of the national championship was on dirt tracks like Fairfield, Illinois. The coin, uh, the 80 [00:13:00] mile, there are a number of trends in, it was actually not dirt and Milwaukee was not dirt, but they were racing those types of cars.

But those were the dirt cars. The, the roasters were really the cars for the pavement. Then, uh, uh, Watson continued to build, continued to define his design, man by the name of JC Ian, combined with a. Superb driver, very aggressive, wonderful man by the name of Parnelli Jones. Rufus Parnelli Jones, and they won the race in 1963, kind of a controversial race.

What happened was that in 1963, a man by the name of Dan Gurney, American Racer had looked at and had seen that the rear engine form of the cars over in Europe were really easy to swept the field. John Cooper, which had started the revolution and it was now a real revolution. This meant that pretty soon somebody was scratched their heads.

John Cooper did bring 61. He brought the Cooper over. [00:14:00] It was undersized engine, but his driver, Jack Grabham, did well, finished ninth with the car, but the car handled beautifully through the corners and everybody recognized that at the same time, Dan Gurney put together the Ford Corporation, Cullen Chapman of Lotus.

And a gray driver by the name of Jimmy Clark and Van Gurney. These four, they basically, they developed a Ford engine based on a stock block, fair lane, believe it be put together a rear engine racing power they brought to Indianapolis. They came within a hair spread of women. It was a controversial situation.

I now, but he had May Car Jones won the race with a, with a Roadster. Jim Clark came back in 1964, but had a lot of trouble with his tires. The tires were being provided primarily by Firestone in these days. Although when he came in 64, AJ FO was no fool. He looked at the fact that the tires were wider on the lotus [00:15:00] in his, and he said, I want to set those tires.

They said, no, no, no, no. What with any of those? Fo said, nothing do. Everybody gets the same stuff. So they had to run out and make a bunch of wider tires, and Foyt went with this car making the favorite statement, I want a hell of a lot of money, this dinosaur, which they were being called at that car. But finally, in 1965, Jim Clark and the Lotus prevailed and basically started a Euro engine revolution for all intents and purposes, wiped out these Roadsters.

I have an example. This is a grown pre car. I, I do not have a model of the Lotus, uh, that, uh, Jim.

But the other aspect of this were obvious advantage. First, you had a much less of a penetration to the air. You could use aerodynamics for down force. Obviously the wall center was [00:16:00] lower. The driver was laying down the engine behind him, the gear box was behind him. The weight center could be, would be different, and things progressed very rapidly until you have this car, which, for example, Bobby S one in 1975.

And as you can see, it’s radically different, radically different from the last Roadster in Indianapolis, which was AJ Floyd’s Box and Roadster. What’s fascinating about all of this too, is that not only was this all informal, it was a whole bunch of guys in Southern California that were doing this. They were all hot waters.

They ex hot waters or ex aviation people. They don’t make enough money out of this. There was a whole slew of, I mentioned Eddie Uzma boy, Travis AJ Watson, a man named Judd Phillips. Luigi, Loki man who made my car, fat Boy Ray, Ew yellow, who made two cars. They’re basically Wass, exactly the same design, but [00:17:00] the was known for this beautiful metal work and that you take a look at the.

The machinery, but under any circumstances, this era is beloved. These cars are loved. They had a wonderful sound and a wonderful presence at the Speedway and for the approximately, well, really 10 years that they were the primary car in the field in Indianapolis. They were fabulously successful and very interesting, very innovative in their own way, and I can tell you also wonderful fun to drive.

Thank you very much.

Michael R. Argetsinger: Well, Joe Freeman has done a wonderful job of setting the stage, uh, with his unique perspective on the Roadster era. Interestingly enough, Donald Davidson was about to come to the podium, came first to Indianapolis in [00:18:00] 1964, the very year that the Roadster won for the last time. Now, Donald was there as a very young man who had written to Sid Collins, who was the voice of the 500.

And Sid was just fascinated by the knowledge this young English man had about the sport. And when he captured the 500, he put Donald on the air expecting perhaps to have him on for two minutes. Well, everyone was in the booth. Was so fascinated by Don that I think he was on for 10 minutes perhaps they invited him back the next year.

He came back as a scheduled guest, was on for a good long time, and after that was, was offered a job and has been in Indianapolis ever since. Now that’s, the story’s not quite as simple as that, but it’s really a wonderful, wonderful story. Donald is distinguished, not only as the historian at the Speedway, but such an accessible man.

He [00:19:00] helps people without question. Not only is he such a source and so to share, Donald is a distinguished radio commentator. He’s also a television commentator. He really has touched all forms of his sport and he’s a much beloved figure in our sport. He’s still a young guy and we’re gonna bring him to the podium right now.

Donald C. Davidson: Alright, well thank you. Good afternoon everybody.

Very nice introduction about the fact that I’m still young. When, um, Michael first asked me if I would come up and do this and, uh, explained what the format was and they were going to do four major racetracks this year and like India Seaway. So my original thought was, which only mentioned a few seconds, [00:20:00] and that is that, well I’ve gotta do a sort of a brief history of the track and, and not 1 0 1 and maybe something pretty close to it.

Immediately thought, you know what, no, I don’t need to do that. Because the people that would come to this, people that are part of this whole movement and the research library and so on, and so anybody that’s gonna come to that, they already know that stuff. Or maybe they don’t care. You know, so many different forms of motorsport and, uh, there’s some people that, although I, I think that everybody there that has a basic impact in motorsport, uh, the Indianapolis 500 is at some point, whether they were looking at it from the Jim Clark point of view, or whether they were looking from the primary point of view, everybody sort of, kind of has a connection with it.

Anyway, I thought, well, probably it would really be backer [00:21:00] if I just basically do q and a rather than just sort of, you know, put my glasses on and read a paper, or, which I, I never do off the top head, but rather than do it from point to begin. I thought that probably we could do a bunch of history based on the questions that you asked me.

So to just so we kind of get into the, the thing a little bit, we’ll do general q and a I don’t think really, I mean there’s all kinds of things like, but you read the already know it or you don’t care and specific you entirely. I’m very fortunate in that I have this, I, I know I’ve worked in United States a couple years, but then it ended up that I went to work for the track.

I actually became a historian in 1998. The title historian. [00:22:00] We think nobody that I’ve talked to, we, we do not believe that there is another racetrack in the world that has a historian that’s on a fulltime staff. Most tracks will have a historian, but it’s either a parttime or a donation of time. But I’m.

And it is a full time job. Believe me, I’m a historian by natures as well as by vocation, being very blessed. I’m not a gearhead. I have no mechanical knowledge at all. When I tell people do q and a, I’m really not into controversy, and I’m sure that there’s a number of the questions that you have will be of a, uh, required going into a controversial area, which I just assumed not do.

But I also, you know, won’t.

I get my opinion on something anyway. I’m not the gearhead. I memorized a bunch of [00:23:00] stuff, para passion. So if you have a question of a technical nature, I can probably give you a halfway decent answer. I memorized your parent passion. I don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, but I’m giving you the answer.

I’m really about the people being blessed to meet a lot and, you know, go to some of their homes and get to know the families and so on and so forth. So I guess just basically whatever you would like to talk about.

Audience: Uh, I just noticed the front of mine sitting on the other side of the, uh, stadium and he’s a, uh, cousin, nephew or something of, do you have any, uh, what was the connection with I.

Deputy Hudson. Oh, he’s

Donald C. Davidson: a Elli. No. Whether you are a relative or not, will depend on how I answer this.

I don’t think so. Andy Elli [00:24:00] just an extraordinary person. I think probably the greatest showman, sixties and seventies, probably the greatest showman ever. Just an extraordinary person in that. Because of his size for much of his life that he is still operated. Because I remember when he had the right turbines and he would be running up and down and I think he was probably 48 at the time and I thought, you know, that guy’s never gonna see 50.

Well, next March he’s gonna be 90. It is amazing. I think it’s March 17th or something. He’s gonna be 90 years old. He has difficulty getting around, but that’s been true for, for many, many years. But he is a sharp attack. He has a really strong deep, he talks hundred miles an hour. I mean, he trips over himself.[00:25:00]

An innovator, although I think that he would like for you to believe that many of the ideas were his own, but I think that what he did was, and some of them probably were his own, but I think he also surrounded in himself with people who were knowledgeable and had ideas and put into, you know, reality what other people had thought might work.

And made a qualifying attempt in 1948. And the trivia about that is that the number of drivers of these kind of cars, by the way, is Wind Lane. A few back here. How many drivers are there living Who drove Indianapolis? 500 in the 1950s, and the answer is five. How many in the forties? None. When Jim McMan passed away, that was, he wrote his day.

He was 49. [00:26:00] So when Jim McMan passed away right before Thanksgiving last year, that was the last of the forties drivers. And so now we have the earliest stock for anyone who’s still living. In 1955, there’s two Chuck and Ruso. From, uh, 57 and in AJ Fot and also from 58. Those are the only 1950s left. Anyway, having said that, the earlier start that you’ll find anybody who’s alive, but there’s 55, what is the earliest year for anyone still alive that made a qualifying attempt?

And the answer is Andy Elli. He, because he made a qualifying attempt in 1948, he’s not the oldest driver who drove on the track, was a guy named Frank, who was a, a midget prior driver, who actually at the Speedway in 1949 took part of the working test. And I think he just turned [00:27:00] like 97, 98 right up here.

But, uh, anyway, so I, I digress. But Elli first came to the track in 1946 and he and his brothers had a company called Frankford. Actually made up a grand operation. They hot waters, they uh, run Northside Chicago. Not only did they hop up cars, they also had products you could buy Blaine products. And then they became car entrance of the speedway.

They had an association called the Hurricane Hot Rod Association, which ran track oysters. Not these, but like.

You actually have to distinguish which you need. There’s track roadsters, there’s these oysters, which are, which is a complete misnomer because those were built for tracks, and the term actually refers as Joe explained really just to the, the, [00:28:00] uh, the book of it car, which just the Roadster. And, uh, by personal preference, attention, you see the term Roadster all the time with a capital R.

My personal preference is lowercase r and because it’s a, it’s a nickname. But anyway, track Roadsters was a huge movement on the west coast right after the. And there were numerous great stars of, of the fifties and, and the sixties that came out of the West Coast Track Roosters. Some of ’em actually, you know, migrated to the Chicago area to be part of the Granite Hurricane Hot Association.

To give you the idea of Track Roadster drivers, I mean, we’re talking Jack Draft, Manny Flaman, Dick and Jim Rathman, pat Flaherty, AJ Watson as a mechanic. All these guys meet each other. Bob Swiper was from Northern California, but he came down to part of it. M Don Freeland, Andy [00:29:00] Lydon, Dempsey Wilson, Bob Scott, Jimmy Davies, and you know, you can go on and on and on and on.

Well, several of those fellow went to the Chicago area, Jim and Pat, and there another guy named Chuck Layton. Satton Layton. Uh, they all went to become a part of the, uh, of the Grati Hurricane Hot Road Association, and then later that became the Hurricane Racing Association. Elli Engine Cars at the Speedway.

I mean, they started it out with our stock off engines, er fors, which were used mercury with, with these lanker heads, and he ended an awfully in 48, which didn’t make it. But from the time you get from 50 on, they were often covered. And he had an impact, drove for him for the equation, and then Jim 52 and then 54.

All of a sudden he just, and quit the time being and sold and [00:30:00] racing. He moved to California and then suddenly back in the, again. 61 when Lou Welsh, who owned the Novi was having a battle with the government and then all of a sudden the Novi team was available for a song and so purchased the Novi and entered one in 61.

Got there late. They, they defended the one car. They were back in 62 with two cars. They didn’t make it again. But then in 63 with three cars, they did something that Lou Welsh had never done. They had three novar in the field, and it was Jim and Bobby race alone. Then in 1966, there was, uh, one of the oddest groupings, I think in the history of Motorsport was the STP corporation sponsored the Lotus team.

So you had Colin Chapman State, [00:31:00] and, uh, Jim Clark with Elli. And when that happened, I remember thinking, oh, I don’t know how long this is gonna last. Elli Chapman and Clark, well, actually the fourth season, except of course Clark was no longer around, but they did the Lotus in, uh. It is 66 with uh, Clark and Al er and then 67 with Clark and Hill, and then the wage disturbs came on the scene in 68 with four.

Everybody thinks there were three of those juror there were four. Then in the meantime, now Galloping Al Dean attached away. Van passed away after the 67 season and his will disassembled. And so then it became the Rey Racing team. There were several teams. If you look like in 67 and 68, you had the John Co Racing team.

The Rey racing team. They were all tired [00:32:00] dealers. How much money did the principal have? It none that all the teams Firestone Good Year. Well, anyways, so, and Reddy did his own thing for 68, and then for 69 there was a marriage between. But more than that, this is one of the biggest surprises I think.

Because many of you probably remember this team on paper. The Lotus 64 rear Engine Lotuses four Wheel Drive, turbo Chair, Ford, Mario, Andre Grand Hill Yak rent. The front row, right? No, they missed the stove. Those cars never turned on the race. Mario had a huge accident in practice and, uh, that car was withdrawn.

And then the other two that, that Chapman as Clint Warner and, and Jimmy McGee had the, uh, the Mario car pretty much, [00:33:00] and then Graham Hill, they were, and then Hill ended up doing for circuit TV or a B, C. So then Elli had moved on and he was on his way to leading the S STP corporation, which he did. I think he, from 74 I think is when that ended.

And he was pretty much ousted as a car owner. His son Vince came back in, but Andy is still had a presence and he put SVP on the map. I mean, it wasn’t a new product. There was a series of business deals that were made in the early sixties involving Spba Ton products, LIC engineering, and all these different companies came together and Andy was, was working for, and they had this product and said, why don’t you see if you could sell this?

And it was SST P, which stood for scientific repeated, and I think it the German [00:34:00] had invented this like in the late forties or something, and it had been around for a while and they said, why don’t you see if you can, you know, sell this? Well by God he did. But stood they there had not stopped yet. And so they took some student papers in ville with, uh, Murphy and Barbara and.

Anyway. Let’s see. I guess I’ll, I’ll wind up here by saying that there were a lot of people that didn’t care to have around. I mean, I know that he was a, in a lot of people say, but he did wonders for motor sport because even with the wage turbines. When they went to Milwaukee and they went to Trenton, they had the biggest prayers they’ve ever had.

And I remember thinking at the time, well, I personally knew an opinion. I mean, personally, I never liked the turbans. I realized, uh, maybe either at the time, very shortly thereafter. [00:35:00] That those cars bought in the general public, a lot of curiosity seekers and maybe that some of ’em, they came once and sold turbine and never came back, or it may have cultivated some base and otherwise, so.

I mean, I think that his contribution for,

Audience: yes.

Alright, Roadsters

Donald C. Davidson: and, uh, when was the last one? And so the last time that Watson with a normal aspirated op with a 2 55 on parish. There were four of those in the 19 five race in 19 six. The,[00:36:00]

and that was, that was a roast with a turbo. Unfortunately it didn’t get very far. There was an accident right at the start that took out 11 cars. That’s the one, there were no injuries. It’s not the bad one you can thinking about. Uh, the only issue was point, we decided that it would be better if he was on the other side of the pants and he scaled the, like, came going up the empire and as he went and.

Anyway, dirty was taken outta that and borough, there was some really good cars taken outta that accident. And, uh, unfortunately, alright, in 67, heard of you showed up and they had two cars. I asked somebody one time, actually there were two and a half of those cars, the third one, but there, and her, the one himself, and [00:37:00] then Ed Rose from Houston, Texas had the other one, which crashed on the morning of the first day.

The whole days where they two groups so you get a 50 curve that they’re all hot at the same time. The reason that I mentioned that one is because it comes back into the picture. Our her qualified this and got bump was the second Alterna starter and it came back the next year with a slightly modified and qualifi that eight.

They called the cars the Mallor. First to be, it was the PepsiCo FritoLay special saw. He burned a piston I think after nine laps and came in and when the car was first through the gate to go back to the garage area. That’s the last time they, a front engine car was in that at the, so you, you want a story about Herby?

I think I know where you’re going [00:38:00] and I’d rather not. I’ll just say that Herby is a very interesting character and, and I hope no family member would take it wrong. Kind of a sad character. ’cause he is remembered for his antics in the later years, his career. He gave him sideways to the officials and find to fight city Hall and losing, and it’s a great shame.

That’s what he’s remember for, because in the early sixties he was very much of a contender, uh, from North, which is not that far from here. He finally, Jones came back together and he set one in four lap track records as of working on the last qualifying day of 1960 with the Travel on trailer special, which was a rebuilt car, which again shows how things have changed a little bit.

That’s the car in which Ed lost his life. Car got upside down. And so what did you do in those days, uh, when you had a fatality? [00:39:00] Well, you prepared the car and got another driver. And so anyway, heard of, he said one in four ACT chiropractor, but he was in the back first day. And then in 61 he was on the front row with the Damer special, no, Damer was a, a slider manufacturer from Niagara Falls.

And then, uh, Herby led the race for that and dropped out. And in 63 he said, we jumped two years, drove in the middle of the front row, led the first flat, great bat, Colonel Jones, and won four national championship races and won a number of sprint car races. And then when he had this terrible accident right after the 64 or 500, he had terrible Indianapolis.

And in 64 he dropped out. They then went to Milwaukee the next week and he was running nose to tail in third place with Dr. Board leading, who being run up in Indianapolis. Second was quite right in the 64, winter running second. And then herpes was right behind with a roots that he and his [00:40:00] brother Peak had built up in the, in a barn.

You know, kind of wonder. They were running literally nose, tail, and Ward had a transmission failure and Foy couldn’t get back up in time. I mean, he got on the brakes but verus ran up over his wheel, hit the wall, and then there was fire and then verus was ly burned. And so he was shipped to the San Antonio Burn Center, but within three months he was out the hospital badly.

And the doctor came in and said, all right, we we’re gonna do an operation on your hands and I wanted to want you to think about this for a few days. We are going to set your fingers and however we set them, that’s how they’re going to be. And he said, can you curl ’em so I can grab a steering wheel? Well, I guess the doctor about fainted when he heard that.

Serious about that. And indeed by the.

He ran through the 65 season [00:41:00] in great pain and you have the, the hands would be bandage and they would bleed and everything, but he was so determined to race. And then in March of 66, at a time when NASCAR was big, but it wasn’t getting the national or international attention, and went down there and he won the 66 Atlanta 500 with Lorenzen running and Richard Petty and David Pearson and all, you know, all the top guns and Bur won the Atlanta 500 and nobody about that anyway, he did not like river engine cars, although he wrote them in several in the beginning.

Believed as did others, John. And there were several people that still thought going into the, you know, 67, 68, 69 time that a lightweight front engine car could still do the job. And so herpes would, would [00:42:00] struggle with the thing. And I know that the popular memory of Herbes is just antics and fooling around the front engine car on, on the last day with no Brook making it.

But in 67 and 68 and 69 and 70, he was dead serious. I mean, he was talking about Paul, the front road in 68, but time had passed them by, I mean, if they had better engineers, it was just.

Uh, to pick up something that I think that either Joe or Michael made a comment. I, it, it was, it was Joe about in 64 that my first year at the track, and if you look back in the years before that, and the years later, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was this wonderful gathering of all these enthusiasts.

And I don’t just mean enthusiasts only, but enthusiasts with the wherewithal. You know, there were other parts of the country where whether you [00:43:00] want to call ’em specialists or they had tunnel version or whatever it was, I, you know, but I mean, typically you tended to define it and don’t take offense, but it seems to me that on the East coast, you were either a mission guy or you were a sprint guy, or you were a stock car guy.

You would go in the hes and, and usually that’s what you stayed with that weren’t very many people that either went from one to the other. And, and now you need to prove me wrong because I know there are exceptions, but for the most part, and even in the Midwest, but it seemed to be that in, on the west coast there was all of this diversity and everybody was into everything.

But I’m talking about hot rods, drag racing, motorcycle racing, and sports, car racing. And a lot of the West coast people. Saturday night, they would be at Astro Park at a sprint race, and then, uh, the next day they’d be at Riverside for a sports car race. Or it would be stock cars on a road [00:44:00] course. And these guys would come back to Indianapolis.

And if you look, do we either, you know, see the films or even look at the photographs of the qualifying jobs from the sixties and the fifties, and you look in the background and see who’s on the cruise. It was unbelievable. You know, d Jeffries, the painter. Was on Parnelli’s crew and also he worked with Point a little Bit Journey, even when you’re into rear ranching cars, Erie had Calvin Rayburn and, uh, sharp and Diary Colburn and Merck Lawwell.

I mean these are bike racers that were at the top of their profession, but they all back to, I mean, Don Ome was never on approved, but I’d seen him in the garage area every year. He would come around and he looked at normally the stock block, uh, engines, but, you know, everybody was interested and involved with, with everybody else.

It was just marvelous Marvel client. Now everybody was a specialist. ’cause these guys are volunteers. I mean, now everybody on a team had a [00:45:00] 401k and you know, travel expenses. They used to travel station wagons and go together. I was talking with Joe earlier about the fact that typically in early sixties and into the mid sixties, there were a number of teams where you had one paid employee on the team.

And it was the chief mechanic and he was everything. He was the aerodynamicist, he was the engine man. And he was also the team manager. Some car owners were very, very much hands on. There were other car owners that were strictly sportsmen. They wore suit the tie, they owned the yachts and race horses and they own a race car.

If you lifted the hood, they wouldn’t know what was underneath it. There were several like that and, and it was funny how I, how many mechanics who refer to it as my car. That was my car. Well, it really wasn’t actually, you know, it was, it was Mr. So-and-so’s car. It was my car, and the car owner was the guy with the suit and hat and the tie [00:46:00] that would come around every now and again and wasn’t particularly welcome in his own garage because, you know, if we need money, we’ll call you.

So you had the, the one guy that was the, uh, the chief mechanic and you would tow the car and everybody else would be volunteer. And they would either meet, you know, at Indianapolis, ’cause that’s where a lot of teams were, were based. And then they’d crane to the station wagon and then they would all drive together.

Or a lot of people, you would pick up the crew. At the time when Jim Rathman won the race of 1960, the only employee was Hiroshima, who was the chief of the candidate. You may have read that. It was smokey, ick. It wasn’t. Smokey was bought into supervisors for pet stops. He was not the chief of the can. But, uh, the point is, when they came to the track, they didn’t have a crew.

They picked one up for race day and several of the people that worked on the winning crew were on cars. Have they missed the show? So Bruce Flower was the chief [00:47:00] mechanic for a Chevy, which hadn’t made it. And I think he did the left front, I think a photograph of him actually doing something with. Well, anyway, he’s in the show.

Al Keller is it May, maybe somebody remembers that name, was the driver of the sprint car driver drove in the 500 and he also went to NASCAR races when they would be hundred backwards on a quarter mile paying a thousand or less. Anyway, Al Keller was Bruce’s driver. He being in the race 5 56, 57, 58 and 59, and then they missed it in 50, so I think he was on the right plan.

Now when’s the last time you had a driver? Missed the show and then they got a job as a volunteer on a fit crew. You know what? Anyway, talked with Eddie j Watson quite a bit, just recently. He was telling me about the people that would come over shop. In Glendale to help build the cars on a volunteer basis.

And I think, [00:48:00] boy, how times have changed. He said that there was one guy, he said, we had a guy named and we paid him $75 a week, but he had like several of his friends, Larry Sheda guy named Lee Boy came one time. He had five guys on his crew all with the first name, George, and they had nicknames five George.

It was Hollywood George, and then there was a guy that had a really strange personality and he was miserable. George, I can’t remember what name was, but said we never built any cars in. He said everything we ever built was in Glendale. But he said they guys would come over after work and help put the cars together.

So they volunteered to build cars, that they were gonna go back to Indianapolis and volunteer to be on a, just to be part of it. And then if they, for, you know. Gave him a couple hundred bucks, so maybe not. But

Audience: anyway, they just unbelievable days. There’s a driver who posted in this [00:49:00] quite a bit, and he was a great sports in the late fifties and early sixties.

Could you just elaborate for some not understand his four?

Donald C. Davidson: Yeah. The gentleman asked about Walt Hans, and I remember when Michael first called me and said, I’m gonna do a book on the history of Walt Hans. I said, whoa, that’s a pretty special subject, because he was sort of revered within those circles. But I think that, you know, a lot of people, even at the.

A lot of people didn’t know who he was. Well, he was 44 when he came to two and half in 64 at that time was the, uh, the oldest, uh, so-called rookie. The first time I think I was aware of Wal Hanskin was that he won the, in 19 59, 58, 59 Silverstone, he won. [00:50:00] With January, March 7th, and I think that probably the first time that I was aware of them, I might have known before that because I would read sport and I’m dating myself here, but, uh, you know, it served 56, 57 and there was a lady named Ruth Sand Spank used to write the report.

So I.

So how he got connected with Indianapolis? I really dunno. I did meet him very briefly. He was quite tall. I think he was about six one, maybe he was tall. And then also I was surprised that he had a very high voice. It was sort a highing song voice. Anyway, so he was part of the Shell Qua Valley. Good luck spelling that, except it’s slightly easier than ky.

He was the, uh, I think it was, he was like a [00:51:00] BMC dealer up in San San Francisco. So how that team came about, I have no idea because it was an interesting bunch, Peter. Was the team manager and AJ Foyt was in the mix to drive one, the first. So there, there were three of them the first year and it was, uh, paper Rodriguez and Wal Kinston, and then maybe Foy.

Foyt actually tested the one which had number one on it. He tested it, I think either like late March, early April, and then. And then he drove it in May, but I think only for one day and then got out of it. So I think he’d already decided in the spring, I’m gonna go like this. But he did take it out one more time and then it became bought by car number 54.

Pedro Rodriguez had a shunt with his, he was out and so was the car because we didn’t do no backups in those days. [00:52:00] There may be another car to drive, but uh, it wouldn’t have the same number in it. So then Walt Ston had the car that was blue number 53. So the thing about both of those drivers is I’d say fine, he had a career at.

And he was a very steady driver who normally he was jacked the very first couple of years, but from that point on, he quite must have been end driver. And then maybe to some people think of what he’s supposed to collapse, but he figured, look, if I just sit out here and run all day and cars drop back, I stay and hunt and I could seven.

That’s, but I mean, who know?

Dropped. Kelly when they went back to Ponzu for the second time in 1958, and the surprise, surprise and surprises was that [00:53:00] Luigi Buso with a Ferrari won the pole. And Phil Hills says that the engine in that car was at Port record. Did anybody know that? Yeah. Okay. That, and again, that shows you how different things were.

We need an engine for this car. Well, how about this one out to Pogo Fatality that killed bunch of people. We, we need that engine. So anyway, and it goes and wasn’t big top 80 car anyway, the fastest of the Americans.

The race period. Actually, actually, Wal plays a little bit of a role in this. At the end of the second lap, not the end of the first lap, often end of the second lap. It was this terrible accident with Dave McDonald and s. Were taken out. They were down for an hour and 42 minutes, and then we started, several things happened with people coming [00:54:00] from the back to the front and people coming from the front to the back, and it was on that day that probably Bobby Marshman stamp himself, the major contender, which is another very interesting person that there seems to be a revival of interest on him.

I’ve asked.

And my answer was, uh, he was Rick near before you had Rick. But anyway, in the back. Wal Hansen came up through the pack and actually ran through for quite a few lap. It would’ve been around the time I, I’m not sure if it would be before or after Hurricane fell back and then was out. But, but you had, was the early leader, Clark was an early leader and then you had Carelli Jones and FO had a great battle for about six laps.

Marelli had the problem with apparently static ity, the fuel tank flow. And so then Foyt was pretty much cruising from that point on with second, second having a fuel mixture problem and having to make [00:55:00] a lot of stop. But, uh, behind all of that for a while, Einstein man third gave a lengthy pit stop at some point, and the pit stop, which it was like maybe a 15, 20 minute stop, and I heard some reports that they thought, well, we’re out.

And Heman said, oh, let’s. You know, and I mean he knew about and Euros and the people brought back to keep going. So he actually was running at the end of the race. He was 13th and quite a few laps behind. And then he went to Milwaukee in August because Lotus with Ford, they run Indianapolis for, they were do Milwaukee and the Trenton.

Hanskin was gonna be a lot driver. And then he crashed in a practice section and then it ended up with the Locus driver were Jones. He came back in 65, I think it was [00:56:00] 53 at this time it was orange and he didn’t have as good a run this time, but he did make the race and dropped out late and got 14th. And then the in 66, he was entered in.

What ended up being the winning. He was entered in the American Red Bull Special, John Ham and Ham came, he joined where down as, uh, he came into the fray at the, uh, 150 mile race at, of Indianapolis First Park with Roger board. But the team for 66, it was going to be Roger Ward, John Ciz, and Wal Hanskin.

That was the original thing. And then Ciz got Kurt, I think it was a can Aex in, and then Jackie Stewart came in as his replacement, even though, so Wal Hanskin was to be in the, uh, American medical car right up to the point where they went to LA mom for [00:57:00] a special test in April. And he, and then I think it was the 24th.

And, and then Graham will gets the car and then goes on to win the race. CTI’s version is that Graham will sell for him and won the race. That if fact, you know, if he hadn’t got then Certainty’s thought that he would’ve won the race. Not quite. There’s other theories here, Roger Ward, that AEW and Bill had head had off, which he wasn’t very happy about.

And in fact, he even said in the years of his life, he said, I thought. I thought I was a number one driver on that team, but apparently I wasn’t. When I signed up, I had won the 500 twice and these two guys had never driven in it, so I thought I was the senior driver, but they, Stuart knew about all the good stuff.

Well, anyway, the, the point is that Hill came onto the team, I think maybe the first week in May. So if you go to the program number [00:58:00] 24 American Medical Special, there is no driver because they pulled kin, but they didn’t have a substitute there. There is a car that is normally on display at the Speedway, I don’t think it’s on the display at the moment, and its painted up as Jacks.

Cooper that that finished in 1961, it isn’t what is supposedly the real one is out west, but the paint driver is wrong. Always reminds me of that. The whole kin empty with the suspension car has been restored. The paint driver is not quite right. The blue is quite a bit off and I know why that is. But anyway, the Hank spent car assets was stored, is a lot darker than it should be.

Oh, the Cooper. The Cooper that is portrayed as Brad’s 1961 car that the museum has came from, Jim Hall, came from Chaparral Cars. There is a possibility that it is. The car of bra drove in the exploratory test [00:59:00] in October of 60 to see. You know, didn’t want to run and try run, which Roger Ward set up. Roger Ward is famous publicly in road racing for driving digits, but he also drove sports cars in road races as well and doesn’t we have enough credit for that?

And he drove a BRM in the 1973 Pro Pri Wakin Glen, did he drive the midget at Seabring? Yes, but he also drove a be on the old circuit. But, uh, anyway, Roger Ward is the one that encouraged Cooper come Seaway when he was down at Sea Horr mid, but he was very impressed with.

To know him, but I, he was just a wonderful person the more he printed them. So rather than being the establishment that said Boo rear ends, encouraged foreigners who [01:00:00] needs them. Board, actually made the arrangements for the test, drove the car, and one of his sons told me that Robin stated at his house when he came in for the test, bring myself back into the fact that the car that is portrayed as finish.

Which may be the one that brought 1960, apparently was the one that Pete Sharp wrote.

Joe Freeman: Yes, sir. Can I just tell one quick story relative to your comments about the friendship between Jack Lin and the Roger Ward? Not too many years ago when they both were alive, I was at the uh, Monte Storage. They were both there, and I was pretty amazed, but I had met both of them.

But briefly, I was just in one part of the area and all of a sudden the two come together and they’re talking animatedly because. Roger Ward is saying, Jack, do you have any of those Repco [01:01:00] parts? ’cause I have a chassis and I want to put together one of your Repco cards. They were talking like two enthusiasts as we would under underneath.

It was, I got a great picture of the two of them talking. They were great friends and obviously two fantastic team.

Donald C. Davidson: Thank you for bringing that up because um, I’m big on the people and I’m looking at books. I like to shots and what I love, you know, I love the candid shots where you see the camaraderie between two people and there’s a wonderful shot that I’m asking that is evidently after and Ward both qualified in 61 and Ward has come by the garage to congratulate on making the race Evidently.

And Brad, who he was a very serious person most of the time and he’s running from ear to ear and there is a, you know, the equivalent of the helmet bag that is on the bench [01:02:00] that is assuming is his travel bag because he’s just qualified and he’s on his wayward has come by and just the camaraderie and the joy between the two of them.

I love that show and, and shots like it. Yes sir.

Audience: I will avoid the obvious comparison of names, which I’m sure Bill Green in the back here knows what I’m getting at. The fact that Jim Raffman real name was Richard and Dick Raffman, real name was James. I just wondered if you would be so kind as to comment briefly on driver who I think is one of the, uh, most underrated drivers ever run.

The 500 Mel Kenyon. Okay. Absolutely.

Donald C. Davidson: And this is something that I think a few of you have experienced in certain age. I have been blessed, as I said a while ago, to come to know these people. A lot of stories that you’ve read or you know, kind to accept this gospel. And when you talk to the people you know, some an and then [01:03:00] others, you know, when you first hear a story from somebody, you think, oh, that guy’s just high his fear and trying to justify here.

And then when you talk to more people, sometimes you find out a lot of what you know other people have said that they’re not talking know, learn that to be true. And you learn about people and you learn about the family when you have an opportunity.

And then you start learning the really personal stuff, then you don’t know what to do with it. And I mean, I’ve learned so many things that I found out that I thought, God, I’d love to run with this, but I don’t think it’s fair of a person. And one of ’em is the grant from me. Now the easy version is that Jim was actually Richard, as you said, and Richard was James.

And when Jim, as we know him, wanted to start racing, he was 16 years old and he had to be 21 or 18, but. Do it legally at 16. And so what he did was to [01:04:00] borrow his brother’s id. And so they basically swapped names. It was a little bit later than Dick, as we know. Him was really James. He decided to race as well.

And so the 1960 limit, Jim Rathman was actually Richard and Dick Rathman, the 1958 James. Well, the true name of Jim Lin. Once in a while you would see it would give, there was a speed age story that he was named as Richard Rathman. One time he told me, he said that my name was actually loyal. R-O-Y-A-L. He said, I’m Royal Richard Ference.

I said, really? Yeah. But he said, I, he said, well, I’m Jim. To everybody he said, he said, my driver’s license says Richard. I knew that for several years, but I didn’t do anything with it. Then when he passed away, I asked the family, I said, now that he’s deceased, what do you think? And they said, yes, that was his name.

Go with it. So, you know, we revealed that at that [01:05:00] time. Right. And I do have another one like that, the daughter of Freddie Aggravation. And Freddy Ion is a very important person in my life, by the way. I, I owe him a huge dealer of gratitude when I’m doing my thanks to everybody. Fred Ion is right near the top, and I asked the one time, I said, this was l I’ve seen occasionally.

She said his name was Levion, L-E-V-O-N, which is an Armenian name. And she said his name wasn’t Fred at all. His name was Levin Ian and Fred was a name that he gave himself. And then another one too was we read about George Francis, Patrick Flaherty. His name was actually George Francis Flaherty Jr. And Pat was a long time nickname.

He was, Patrick was not in his name. I knew him a little bit back. He was deceased of his wife. She said I was from Chicago [01:06:00] and he came back and, and she said, when I first went back to California to meet the family. And she said, I kept hearing him talk, George. And she says, who’s George? And you know, the older called him George.

That was his real name. Oh, there’s another one, an coast driver from Manhattan Field, New Jersey named Mike McGill. His name is Charles Edward McGill. Mike was a nickname. So anyway, sorry, what the hell you,

Mel Canon Kenyon was, I think without question, probably the best, if not the greatest, Mr. Car driver of all time. Then I think certain, since post World Wari, Bob Sson gets a lot of votes, but I think unquestionably with Mel Kenyon’s accomplishments is absolutely phenomenal and he won that national championship seven times and the total number of [01:07:00] victories, I think ended up being.

But he actually had more seconds that he had first see, and I’m just talking he national chapter. I’m not talking associations. So how many total races did Mel.

He national wind. And then I think if you take the first seconds and thirds, they don’t call him podiums and but the total number of four seconds and thirds, I think you’re probably talking about four 50. He did a lot of his own mechanical work with his brother Don all jumped to the speedway because he was actually at the track in 1965 with a Roadster which qualified and got bumped.

And then it was months after that that he went to L on Pennsylvania and then had this accident. There was four car accident and he was basically momentarily stu or knocked out and there was methanol [01:08:00] fire. The thing with the methanol fire was that you couldn’t see it unless it got really hot. And I’m sure that I, I’ve had a personal look at a methanol fire a couple times.

I’m sure that some of you have maybe many. That’s why I would describe it. It’s like a heat ha, a shimmering heat. Ha. You can’t see the flame, you just see this ripple and with the distortion in the color behind it. And then if it turns orange or yellow, then it’s time to maybe find another base go. So this fire set and this, and by the time they got in there and got hanging out, hand was burned.

So her had already been to the burn center and back out. And so that’s where they put him in for three months. His situation was a little bit different because rather than make the decision about how do you want your finger set, which is what they did with, it, ended up that they did two or three [01:09:00] operations and that he ended up with no finger tone, the left hand at all.

He just had a to. And so he was already devising away to come back and go racing with his brother Don and his father. They devised this glove that would slide on to the left hand and then be tied so that, that they wouldn’t fall off and where the palm was, that would be a rubber of gr. And on the steering wheel, it would be a stud.

And so what you would do is to grab the, the right hand, and in the left hand you would basically be steering with the palm. And so this worked that very well with Richards. In fact, he said, you know, I’ve even got in advantage here because if I get in a tight spot, I can do a 360. I just take the bike hand off and I, and I can do one of these if I need to move in a hurry.

And, and my colleagues can’t do that. So then he came to the speedway, he, he was out for the rest of the summer. Mason, come back in 66 in, in the spring. And I don’t remember when he had [01:10:00] the first wing, but he was making the right off the bat and. So there was the concern about coming to the speedway, will he be able to pass the physical?

So there was some discussion, but several people went back for him and then they decided, okay, well, you know, we’ll we’ll give you a, you know, a temporary or probation. We’ll take a look and say how you do. Well, the 66 race, he just kept running all day and, and it was a huge attrition and he ended up, and then in 67 he got taken out late, like Hale yer back in the days when we had a really interesting mix of drivers.

I mean, we didn’t have people that were out advice. We had the best at the best when they were at the top of their game. So here, Hale yer and we y

and Mel wasn’t very happy that, but he got a third in 1968. It’s a second was third. Dennis Holmes was fourth. [01:11:00] Lloyd would be spare 69. He was poor off Mario on Gurney was second. Bobby er was third, and Mel was poor off with Peter Reson behind him, although Revson in a Distant was down and some major names behind it.

But admittedly, they both had mechanical but canyons with a very, very steady murder. And then he had one more fourth, and that was in the rain in 73. But I, he’s.

65 and now we’re talking the winner of 67 68. And he’d driven for Fred Gerhart in the 67 race with promo king sponsorship. And Fred Gerhart tells Don and Mel in the spring, he actually took it upon himself to try and raise the money. Now they were trying to get $15,000 and they, I don’t think they got close to that, but they did have a bunch of local businessmen and friends and people gave them a hundred dollars and somebody would give them [01:12:00] $2,000 and they raised enough money and they ran the cars.

The city 11 Indiana. But here’s the point, and when you hear about commitment I about this, Don was the chief mechanic. And he was the only paid person on the team, and I think he got $150 a week. Mel Kenyon was his own engine man. He only had his fingers on one hand and he wasn’t born like this. He’s adjusted to this in, in the last couple of years.

And so they had one off the engine purple trash talking, uh, when that was a fairly new engine. And they had a crew, Mel, he was in charge of the engine and they didn’t have engine lease programs in those days. When you got an engine, it was yours and you tore it down and put it back together, and he was the only person that left on the engine.

And then also he had agreed to drive for 40% of the prize money. What [01:13:00] was Mel? Ken’s retainer. Zero. He was the driver and the engine man. And his guarantee was zero. If they missed the show, he would’ve got nothing. They made the show our dropped out and they ended up finishing third. But I think that is absolutely extraordinary.

I may have bought Campbell once again was the refuel finished third, so the prize money was substantial, so he got 40% of that, but he went into it with no guarantee at all. There is a little change in that will involve several names that you’re familiar with, and that is the fact that late in the race, Kenon was running.

Fourth and third was Dennis Holmes. Leonard dropped after the turban. So then late in the race it was Bobby Ster was leaning. Dan Gurney was with the, Dennis home was third with a, and then Mel. Dennis Hol came in, made a [01:14:00] stop because he had a tire going down and the jack didn’t work. Now this is gonna sound like a made up story, but I saw it myself.

It was a length stop and it allowed King to go third and, and home ended up fourth. On the last stop for home, and I think it was like maybe lack 1 94 or something like that, that Jack didn’t work. Gordon Johncock was out the race and dressed in cities, and Foy was out of the race and dressed in cities and they were staying there watching this.

They jumped over the wall and with a couple of other crew members, they lifted the rear of the car up. He was AJ Foy, the defending winner of the race, and last year’s 24 hours of Ramal winner and he’s lifting the thing up by the axle so that they could change the tire. He was a Goodyear car. It was Firestone.

That wouldn’t have been tell you John helped so that they could get that wheel [01:15:00] changed and then home and off finish. Four supposed be talking about Ken. His Speedway days were pretty much over by 76 was the last time, or 77 he. But he continued running mids until about six or seven years ago, and then, then he, he finally retired.

But I mean, he was just the nicest person that you could possibly meet. Just a very fine, fine person. And I, I know I’ve been talking a lot. I wanted to throw this out from the time that I first showed up at the scratch. I had met a few drivers. I had met Jim Clark and I met Bob Ard, and I met last lesson to, to, to stir up, end up in the past.

But when I came to Minneapolis and I thought I knew quite a bit about it, probably the biggest surprise that I had was how friendly and down to earth. The drivers were, I was amazed. I thought that Indianapolis 500 drivers would be very [01:16:00] intense. You know, looking at the photograph and considering what they did, I thought they would be very, very intense people.

I thought they would have handlers. I thought they would have an entourage and they didn’t. Almost every. Which frankly notes that I said almost everybody. A couple had a little bit of an edge, but for the most part they were extremely nice people. You know, Lynn Sutton, Bob Christie, Chuck Stevenson, Bobby Marsh Jones, they were all really nice people, and even some of the ones that I thought would be tough guys.

And so then as I had a chance to sort of then come back and, and work with USAC and be around them and then get into other areas. Richard Petty is a really nice guy. David Pearson is a really nice guy and a lot of the wrong writers, and I have to say that I, I have no idea how many. Formula One, NASCAR.

SECA. [01:17:00] I’d say just about every driver that I’ve ever met and sat and talked with one-on-one is a nice person. I mean, that’s a constant and like I remember Han how Franon.

Audience: Delightful.

Donald C. Davidson: Just a really sweet person. Kel Reto. Anybody meet ato? A lovely bloke. I mean, I’m thinking of it as like, you know, aand was, but I thought he was Mike Kelly ato and I think he wrote for Ferrari for five years, the nicest, sweetest guy that you could meet.